This contribution to the journal Landfall gives an account of a settlement in New Zealand dating from the mid-1870s, when a group of Ulster Irish families, led by the enterprising George Vesey Stewart (1832-1920), arrived to cultivate and build new lives in the Western Bay area of the North Island. Many thanks to Duncan France for putting us in touch with Sandra Haigh, Community Heritage Services Co-ordinator, Kaiwhakarite Ratonga Tikanga Hapori, of the Western Bay of Plenty District Council, who first explained the origins of the settlement for us. The New Zealand writer and broadcaster Alan Mulgan (1881-1962) was born and brought up here, and his memories of those early days have been prepared for our website by Jacqueline Banerjee.

y FATHER’s family and my mother’s came to New Zealand in the seventies as part of a settlement from Ulster organized by George Vesey Stewart. The site for the settlement was Katikati, twenty miles on the Auckland side of Tauranga, in the Bay of Plenty. I was born there. Vesey Stewart was a man of vision and drive, an Edward Gibbon Wakefield [(1796-1862), an even more ambitious coloniser] on a small scale. He planned a transplanted society of gentry and farmers; the first would provide the capital and a congenial [181/82] social atmosphere, and the second would do the farming. Vesey was far-sighted enough, however, to picture the farmers as owners, and insisted that all of them should take out some capital. He inspected a good deal of New Zealand before he chose the Katikati block. He fell in love with the locality, and believed — somewhat erroneously as it turned out — that it would meet all the conditions of his plan. It was an attractive spot—spurs clothed with fern and tea-tree running down from bush hills to the Tauranga harbour, with river flats here and there, a land of streams in a good climate. So he collected his colonists and shipped them off. Indeed, and in this he was like Wakefield, he had begun to canvass before his land was allotted. The gentry brought with them books, plate and pictures; the farmers some knowledge of farming. There were two generals, a major, four captains, and three clergymen of the Anglican Church [See An Ulster Plantation: The Story of the Katikati Settlement, by A. J. Gray (A. H. and A. W. Reed)].

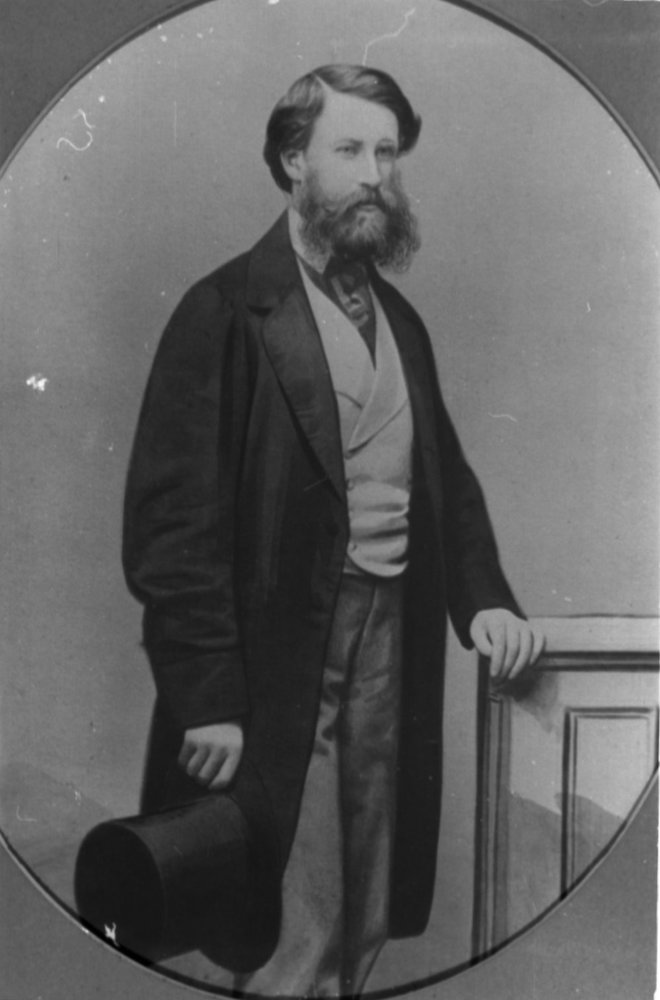

Left: George Vesey Stewart, founder of Tauranga, elected first Mayor of Katikat in 1882. "It is believed that he enticed over 4,000 people to settle in New Zealand" ("George Vesey Stewart"). Right: Katikati, Western Bay of Plenty, from an aerial photograph taken by Whites Aviation in 1954, in the New Zealand National Library, ref. WA-35947-F, reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

The reality turned out to be very different from the dream. The land was not as good as Vesey had thought, and there was little or no market for what was grown. Katikati was suitable for neither sheep nor wheat. The settlement struck the depression of the eighties. However, the settlers managed to live fairly comfortably. Wants were few. Food was seldom short. Money came in from Ireland. Men found wages work of various kinds, and some enterprise was shown in starting new industries. This is a common condition in pioneering society. Socially, the gentry and the farmers kept their places, but settlers helped each other regardless of such distinctions, and there was no class feeling. Good comradeship prevailed, and people got a reasonable amount of fun out of life. Before long Waihi township grew up round the famous mine, and produce of various kinds that it needed could be obtained most easily from Katikati. This tided the settlement over the period till dairying developed. Today Katikati is one large dairy farm, dotted with plantations and gardens. It is as pleasant an example of successful development arising from planned emigration as one could wish to see.

In his recruiting, Vesey Stewart circularized the Orange Lodges of Ulster. An Orange Lodge was set up in Katikati, and the settlement’s one hall was the Orange Hall. On [182/183] "The Twelfth," Lodge members paraded in their regalia. Not that this made any difference to the standing of the two or three Catholic families. The Protestants were on perfectly good terms with them. But the distinctively Protestant nature of the settlement was an important factor in its relationship with the Old Counry. The settlers belonged to the ascendancy party in Ireland. England was their motherland as well as Ireland. When they spoke of "Home," as they did habitually, it was Ireland-England they meant, with Scotland perhaps as an attachment. It took me a good many years to get to know and appreciate the other side of the Irish question.

It was this community that gave me the deepest impressions I received between childhood and the verge of manhood. As a small child I went to school in Katikati, and all my holidays from school in Auckland were spent there. It so happened that nearly all my companions were grown-ups, who had been born in Ireland. I was the one grandchild on the spot in a large family. At a most impressionable age I was a member of a remote society in process of finding itself. It was tied closely to the society from which it had sprung in Ireland, but by force of circumstances was rooting itself in a new world. Most of the older immigrants settled down fairly happily in their new home, but the thoughts of all often went to Ireland. They were transplanted Irishmen, just as in other parts of New Zealand immigrants were transplanted English or Scots. English mail day, once a month, was an event. Many of the families had someone at the Post Office to pick up letters and papers after the coach came in — letters with news and gossip from relatives and friends left behind, various reminders of life in a deep-founded and well-ordered society; letters with remittances, and letters without. In family circles there were scrambles for English periodicals — Punch, the Graphic and Illustrated London News, the Boys’ Own Paper and the Girls’ Own Paper.

Tauranga, Western Bay of Plenty, from an aerial photograph taken by Whites Aviation, in the New Zealand National Library, ref. WA-35171-F in 1954, reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence.

For many years Katikati was isolated. To get out was a bit of an adventure. One party took twenty hours to go from Athenree to Tauranga, thirty-five miles. There was little money for travel. Our society was remote and self-contained. It was far away from Auckland, and much farther from Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin. Indeed, in spirit, Belfast and London were closer to the Katikati [183/184] settler than our southern cities. He had seen Belfast, and if he hadn’t seen London he had a pretty clear idea of it, whereas New Zealand south of Auckland was only a shadowy picture. In those days London was much more vivid to me than any New Zealand town but Auckland. I had read of it in books and seen it in pictures. I think, too, that in our little community English politics loomed a good deal larger than New Zealand. At any rate I don’t remember many discussions about New Zealand affairs. The immigrants brought their politics with them. To most, I fancy, Gladstone was the villain of the piece (for one thing he had disestablished the Irish Church), and Salisbury the saviour of his country and the Empire. When Britain and France came into sharp disagreement over Fashoda in the nineties, someone said: "Thank God Salisbury’s there!"

There was a good deal of reading. Some of the homes had excellent collections of books and there was a public library, also that institution with a typical Victorian title, a Mutual Improvement Association. Books were decorous.

We asked no social questions — we pumped no hidden shame —

We never talked obstetrics when the little stranger came.

We liked adventure and happy endings. A new novel by Stanley Weyman caused excitement. Mervyn Stewart, our neighbour at Athenree, had discovered another new writer, Rudyard Kipling. It was Kipling who wrote the lines I have just quoted, about the three-volume novel. The mood of those verses was the mood of the time — villainy well punished and virtue triumphantly rewarded.

I left ’em all in couples a-kissin’ on the decks,

I left the lovers loving and the parents signing cheques.

In endless English comfort by country-folk caressed,

I left the old three-decker at the Islands of the Blest!

We did our serious reading; Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, for example. In Mervyn Stewart we had an enthusiastic single-taxer, who vainly tried to convert the electors. But I doubt if anyone had heard of Karl Marx.

I had a free run of books, but naturally at that age I preferred stories of adventure. We had Mayne Reed, Kingston, and Ballantyne. Coral Island was one of my earliest books. I read it several times. It is still a favourite with the young. In the Boys’ Own Paper there were the public- [184/185] school stories of Talbot Baines Reed. I thought it must be the finest thing in the world to go to an English public school. A real man from a public school had a halo round him. Does anyone read The Willoughby Captains now? I re-read it a few years ago, and it seemed to wear pretty well.

The tendency of life in Katikati was to bind us to Britain and her established order—her politics, her navy and army, her Empire, her literature, her ways of thought. More or less, the rest of New Zealand was in the same state. New Zealand communities were bounded by narrow horizons. Take our little settlement in the Bay of Plenty, a small group of struggling farmers but recently come to this land. It would have seemed absurd to them to think of them selves as part of a nation. How could this new land, with its tiny population, make things that could compare at all with those of Britain? It was agreed that what was British was best. How could New Zealand form challenging ideas, write books, compose music? What had it to say worth saying? Romance was something that belonged to other countries. Rider Haggard, whose books we devoured — was there ever a thriller like King Solomon’s Mines? found it in Africa; Mayne Reed and Fenimore Cooper among the American Indians. Those countries were different. We hadn’t any history worth writing about.

We didn’t know that the deeds of American scouts and rangers had been parallelled in our own country only a few years before our settlement was founded. In a vague way we knew there had been Maori wars. Katikati settlers were actually occupying confiscated Maori land, and it is significant that I had no knowledge of this at the time, or for many years afterwards, till I discovered that fact during historical research. The local Maoris gave no trouble, and we saw little of them. We were taught no New Zealand history, at home or at school, and this was true of Auckland as well as Katikati. Another significant point is this. When I was in Tauranga in my teens, no one thought of taking me to see the old Mission House, "The Elms," at one end of the town, or the site of the Gate Pa fight, a little way out of the town at the other end. "The Elms" is unique in its combination of age, association, and careful preservation. It is now one of Tauranga’s show places. Fifty years ago it was not regarded as history. We were too close to its story, and most of the older people had come from oversea. It is history today. [185/186]

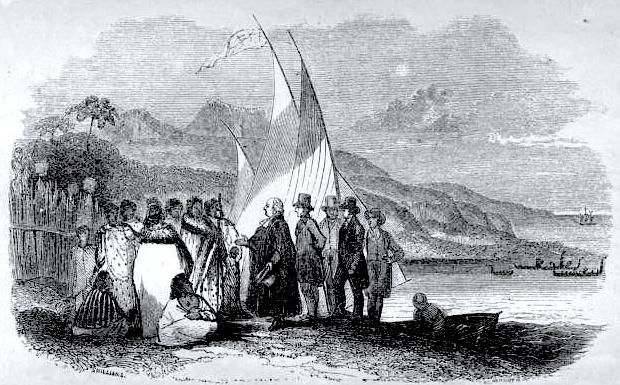

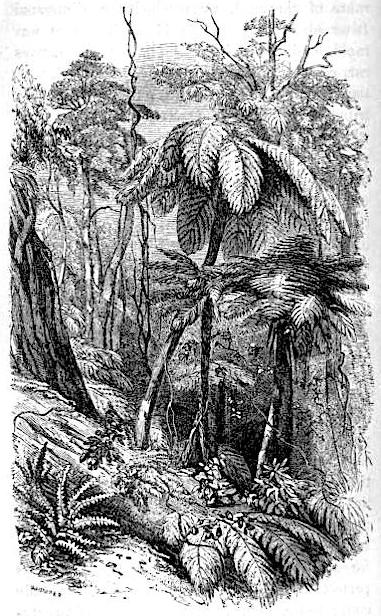

The history and the land. Two illustrations from the Annals of the Diocese of New Zealand. Left: Landing of the Rev. S Marsden in New Zealand, 19 December 1814, frontispiece. Right: The Forest, facing p. 103.

Nor were we instructed in the wild life of our country, the birds and the trees. True, the landscape made a deep and life-long impression on me. It helped to form my mind and ultimately coloured my writing. There were the blue hills behind the farms, the slopes to the tidal estuaries, the rivers and creeks, the scent of fern and tea-tree. There was the sense of space. From the top of Hikurangi, behind the Johnston homestead (Canon Johnston was my grandfather), you could see the sweep of the Bay of Plenty down towards the East Cape. In another direction, stretching away into the distance, was a tumble of bush-clad hills. There was the solemnity of the deep bush if you cared to find it. The Bay of Plenty was the south-eastern limit of the kauri. It was frontier country, with the appeal that a frontier makes to a boy. I have seen nothing in my life that comes so plainly to me as that old Katikati landscape in the full tide of summer. Even now it gives me a heartache to think of those days.

However, as I have said, there were limitations. We were not yet fully rooted in the soil. The homesteads had their shelter belts of exotic pines, and inside these were gardens and orchards of English flowers and trees. Roses bloomed in the gardens. Jasmine and dolichos covered verandahs. The sheltering pines seemed to cushion those pioneers from the full influence of their adopted country. They did their daily work — the men especially — in a New Zealand environment, but one can imagine them retreating to the Old Country atmosphere of their homes — English books and periodicals, English pictures, English letters, talk of England and Ireland. Yet the process of union was going on slowly. The Old Country was blending into the new. Years later I tried to put the Katikati settlement into verse, the imaginary golden weding of an immigrant couple. I wrote this: "A new world touched with old, brave in the making, beautiful and bold."

The grey warbler or riroriro, source: Department of Conservation (NZ), under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY 4.0).

So life in Katikati gave me deep feelings, but little accurate knowledge. I knew little or no New Zealand history and could name few New Zealand trees or birds. In those long summer days a bird often sang. Its song had a lovely cadence, sweet but melancholy. Its music would drift through the long ecstasy of afternoon, and I came to associate this with the happiness of those summer holidays. I carried that memory to my life in the city, and later that same bird sang in my garden. But the point I want to emphasize is that no [186/187] one in Katikati told me the bird’s name. I don’t think anyone was interested. I did not find out until years after that it was the riro-riro, or grey warbler. In some verses about the riro-riro I described its song as "half joy and half regret." By then I had come to be a friend of that great authority on the Maori, James Cowan, and he told me that the Maori thought of the riro-riro in the same terms. That was a stage in my education as a New Zealander. Some years after that I was walking in the bush at one of Wellington’s eastern bays with a refugee from Europe who was well versed in music. We listened to the riro-riro. "Why" said my foreign visitor, "that bird is better than the nightingale."

Grey warbler song, courtesy of Department of Conservation | Te Papa Atawhai (free to reuse).

This was some forty years after my Katikati boyhood. Meanwhile the homestead had gone, and I had taken my children to see its site. In this country the descent of melancholy and decay upon country homes and their surroundings is swifter and more noticeable than in England. The choice of material makes such a difference. A brick or stone homestead is the exception in New Zealand, whereas in England it is the rule. A building in brick or stone may stand for years empty and uncared for without losing its solidity and dignity. If a wooden house is to last, let alone preserve its self-respect, it must be carefully tended. Build a house of heart kauri, keep it off the ground and paint it regularly, and its life will be astonishingly long. The historic house at Kerikeri, in the Bay of Islands, dates from 1819. But neglect a wooden house, and wind and weather work havoc on it. Failure to paint reduces it to a slattern. Uncared for, the verandah sags, the weather-boards rot. And in parts of New Zealand, where the climate is warm and the rainfall abundant, the garden becomes a ruin of unchecked growth, and native bracken and shrub quickly obliterate pasture.

There are a good many such places in New Zealand, and the melancholy that surrounds them is distinctive. In their crumbling timbers and riotously conquered gardens, there is a pathos hardly to be found in the more durable conditions of England. Often they are mute witnesses to failure of some sort, and isolation deepens the poignancy. In England the uninhabited and neglected is supported, as it were, by its neighbours, like a weak soldier between stronger comrades. You may fill in the New Zealand story as you like—the advance into virgin country, the high hopes and energy of youth, the felling of bush and clearing of scrub, the making [187/189] of a home. What happened? Perhaps this outpost garrison moved to another site, or farmed elsewhere, or retreated to town. Perhaps other adventurers took on the property and failed. At any rate there it stands, that decaying house, amid its shelter of funeral pines. The shed is nearly on the ground. A few apple and peach trees lift scaly branches above the high invading fern. A plane tree and a holly keep - each other company, and perhaps find consolation in whispers about England. On the front of the verandah there are still some trailing roses. Advance into the farm, and growth of tea-tree and fern, or plants of the bush proper, bar the way. The air is warm with scents of New Zealand soil, an aromatic tang touched maybe with the sweet decay of the bush. These are the conquerors. The English rose, verbena, and jasmine, are doomed.

Even in drier, and in winter, colder areas, where there is little or no fern and scrub to take charge when the farmer's hand is withdrawn, there is a similar melancholy about a deserted homestead. To some minds indeed, the very barrenness of the landscape — tussock everywhere, unrelieved by trees, and the shoulders of bare hills making hard lines against a steely sky — may accentuate the sadness of frustration and decay.

Over the meadows that blossom and wither,

Rings but the note of a sea-bird’s song;

Only the sun and the rain come hither

All year long.

The Johnston homestead, which, with its surroundings, meant so much to me, did not last very long. Built of kahi-katea by men ignorant of the borer’s special fondness for that timber, it began to crumble to dust, and had to be pulled down. But the setting remained — at any rate in my heart — and I returned there, eager to show it to my children. A new and smaller house stood among the pines, now larger and more sinister. In the garden there were a few struggling relics of the good old days. Back of the house, up the hill and down by the creek, was a wilderness. The present occupant, busy with his cows, had no time to check the invaders. Fern and scrub and bush had triumphed. The once open creek-bed, where we used to bathe and bask in the sun,

A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts,

[188/189] was now a jungle in which we lost our way. I wanted to show the children the old bathing place, but I couldn’t find it.

Never before had I realized so fully the obliterating power of North Island nature. Yet there was something in those stalks of bracken as high as my head, the unconquerable tea-tree scrub, the tall straight rewa-rewa trees that had shot up here and there about the hills, something that was my own, an essential fruit of my own land. They were enemies, watchful ever for any relaxation of man’s vigilance, but in a sense they were friends. They were my possessions, like the warm summer scents spread over the landscape, and the quiet solitude of those hills. The sun still shone, the larks still sang, as when I was a boy; the tea-tree still swung its delicate perfume through the air; the riro-riro still sang of joy and sadness; the peak standing sharp against the blue sky still looked down on farmlands and tide crawling over hot sand into estuaries, the harbour bar on which breakers tumbled lazily, and beyond, clean of officious sail, the open sea.

I realized two other things. It was a changed land. The settlement was almost unbroken pasture, and such pasture as we had never known in the old days. Land that we had considered of little or no value, and left in scrub, was now smooth dairy farms. A new generation was reaping a richer harvest, and making its own associations. My own melancholy, now slightly sweet, now near to tears, was my own and no one else’s. No one but myself could recapture my lost youth. No one else could people those hills and glens, those depths of pine groves and cool damp recesses of bush, with my own Mayne Reed and Kingston heroes, and my own dreams of fame and glory. My children, picnicking there with me by the stream, could not be expected to feel about the place as I did. The younger generation must make its own memories.

Bibliography

[Illustration source] Annals of the Diocese of New Zealand. London: SPCK, 1856. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 14 June 2025.

[Illustration source] Buller, Walter Lawry. A History of the Birds of New Zealand. Vol. I. 2nd. ed. London: Buller, 1888: facing p. 126.

" George Vesey Stewart." Caption information as well as photo credit (with thanks) from Te Ao Mārama - Tauranga City Libraries Photo 01-632.

Mulgan, Alan. "Two Worlds: A Chapter of Autobiography." Landfall: A New Zealand Quarterly Vol.1, no. 3 (September 1948): 181-89. Internet Archive. Web. 14 June 2025.

Created 12 June 2025

Last modified 16 June 2025