[The following passage from the Chambers 1838 Gazetteer of Scotland appears on pages 372-80. — George P. Landow.]

lthough Edinburgh is one of the oldest royal burghs in the kingdom, and was in the twelfth century one of four such towns honoured with a kind of jurisdiction over the rest, it is not one of the earliest settlements of population in Scotland. Passing, however, over the early ages, where history is half conjecture, we find it, in 1128, a royal burgh, extending between the castle, which must have been the cause of its existence, and a point half way down the hill towards the Abbey of Holyrood.

The Earliest Domestic Architecture

The style of domestic building which obtained in the better order of burghs about that time, was just one advance beyond the primitive cottages which gave shelter to the peasantry. From a specimen in the town of Perth, which was only destroyed in the last age, after having existed by the unquestionable evidence of charters since 1210, it would appear that a good house, such as might be occupied by one of the better order of merchants, consisted of one strongly built ground-flat, with a more flimsy superstructure, perhaps of wood, having an open gallery or balcony in front. Specimens of such buildings exist to this day, in the Grassmarket, Cowgate, and Pleasance of Edinburgh, with apparently little alteration from their original condition, except what consists in the substitution of slate for thatch. There also seem to have been varieties from this description. For instance, a house in Musselburgh, which, in 1332, must have been the best in the town, as it was selected to accommodate the Regent (Randolph) Earl of Moray, who took ill and died there on his march to England, consisted of but one flat; a door and passage in the centre, and or: each side a small room, vaulted above, and lighted by a window to the street. If we may judge, moreover, from some of the old specimens mentioned as existing in Edinburgh, the second storey sometimes projected over the first, so as to form a sheltered piazza, possibly used for the exhibition of merchandise. Perhaps such superstructures were sometimes after-thoughts, and were simply reared by projecting strong beams into the street, raising a skeleton wall upon what already existed, for the support of the new roof, and then enclosing the front with deals.

Thus the earliest idea we can form of Edinburgh would represent it as a hill-built hamlet in the shape of a double row of one-storey, or at most two-storey houses, extending from the esplanade in front of the castle, down to the present Netherbow, — on the north side a ravine filled by a lake, on the south a similar hollow filled perhaps by a marsh — one entrance to the town by the bottom of the declining street, another by a narrow crooked path-way, which ascended from the south, near the castle, (since formed into a street and called the West Bow) —in all directions around, the forest of Drumsheuch, through which yet roamed the white Caledonian bull, the wolf, the elk, the boar, the deer, with many other animals, now hardly known in Scotland, which we are assured, did then form the objects of the chase.

The buildings, such as we have described them, were all reared upon pieces of ground, which it was necessary to feu from the king, or other proprietor, by an arrangement styled, in the old charters, a tenement or holding of land. Hence, by a curious metathesis, the houses themselves came to be called by the word tenement or the word land; which are still, both of them, but especially the latter, part of the familiar language of the inhabitants of Edinburgh. Tenement, as a word for house, is used everywhere in Scotland, in reference to any species of street building; but land, from its being so long applied exclusively to the tall houses of the old town, which were so invaribly divided into flats, is only at this day applicable to that description of mansion, and is confined to Edinburgh. Formerly, when houses were not numbered as now, many of the houses of the Old Town were generally known by some far-descended name which had been attached to the word land at the time of their erection, as Gavinloch's Land, Todrig's Land, &c. The word turnpike, which properly referred to the spiral stair leading to the different flats, was another word applicable to those buildings, which really did require some such distinctive appellation, as they were in many cases as populous as some streets in the more modern city.

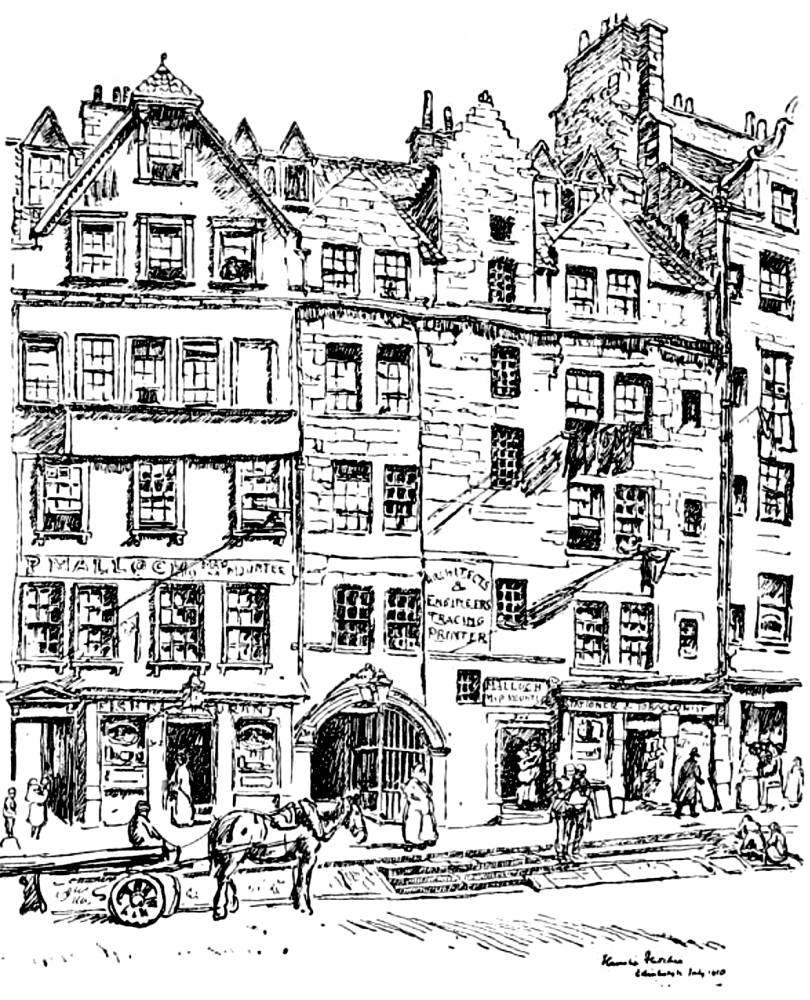

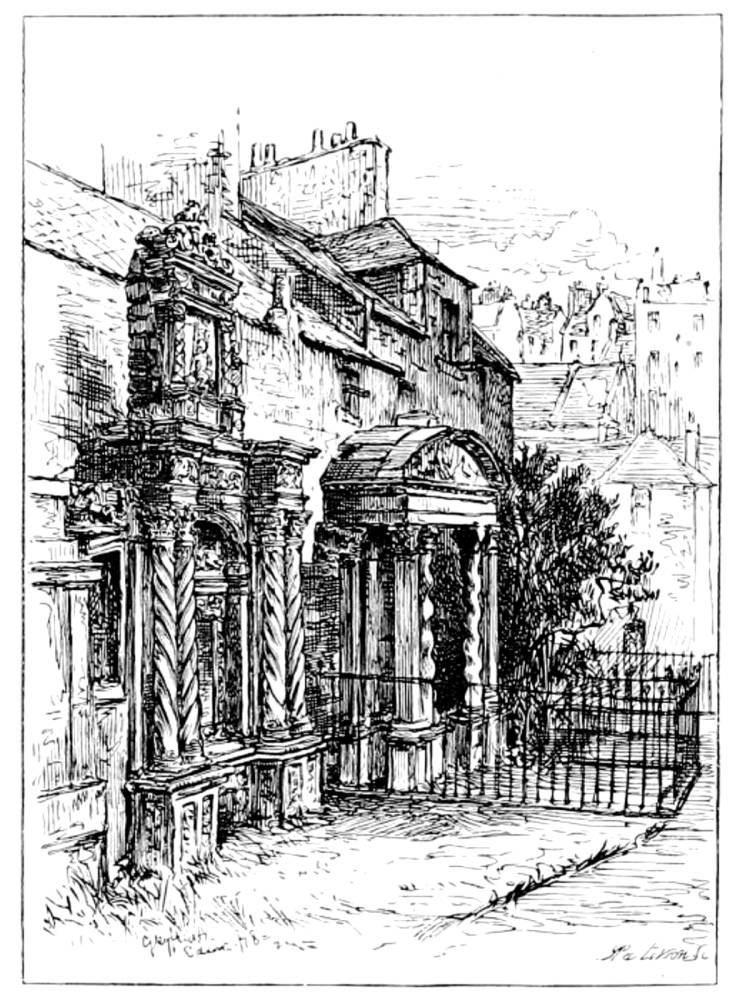

Left: Houses in the Lawnmarket. Right: Brodie’s Close. Right: Bakehouse Close. All by Hanslip Fletcher. 1910. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The second stage of Scottish burgal architecture gives houses which in no respect differed from those above described, except in their consisting of three stories, the lowest of stone, the two uppermost of wood. Of such a style, there are several excellent specimens still entire near the head of the Cowgate of Edinburgh, on the north side of the street. The stair is generally lighted by round or square holes in the wooden deal front, which used to be called shots, or shotwindows, and never were glazed, though in some cases provided with sliding shutters. The other windows were generally half of wood, half of glass: that is to say, in the lower part of the window two shutters, (with an ornamented upright in the middle,) which might be closed in bad and opened in good weather; while in the upper part was an ordinary frame of glass, not formed for opening. We should suppose that houses of this order prevailed in Edinburgh, as a better class of mansions, about the end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centsries. Froissart's description of the town in 1384-5, in the translation of Lord Berners, is in the following terms: —

They arrived at Edinborowe, the chief town in Scotlande, and wher in the king in time of peace most comonly laye. And as sone as the Erie Duglas and the Erie Morette (Douglas and Moray) knew of their comynge, they wente to the hauyin and mette with them, and received them sweetly, saying, howe thay were rycht welcome into that country: and the barons of Scotlande knewe richt well Sir Geffray de Charney, for he had been the somer before two months in ther company. Sir Geffray acquainted them with the admyrall and the other knychtes of France; as at that tyme the king of Scottes was not there, for he was in the wyld Scottyshe [the Highlands]. But it was showed these knychtes that the kyng wolde be ther shortly; wherewith they were well content, and so were lodged thereabout in the villages; for Edinburgh, though the kyng kept there his chief residence, and that it is Paris in Scotlande, yet it is not like Tournay or Vallenciens, for in all the town there is not four thousand houses. Ther it behoved these lordes and knychtes to be lodged about in villages as at Donfermelyne, Cassell [Kelso], Donbare, Alquest [Dalkeith], and such other."

Immediately after, Froissart represents the Scots as displeased at the arrival of the French, dreading more the mischief they would do by eating up the country than the English could by burning it, seeing that they could build up their burnt houses again in three days, if they only had four or five sticks, and boughs to cover them.

The extent of Edinburgh in the middle of the fifteenth century is indicated very exactly by the wall then built around it. It as yet consisted simply of the High Street, from the head of the present Castle Hill to the bottom of the Netherbow, with perhaps a few short alleys on both sides, the increase, hitherto, having taken a direction upwards into the air, instead of extending over more ground. Between 1450-1, the date of the wall, and 1513, when it was necessary to extend it, the Cowgate, the Grassmarket, and probably a good number of new buildings in the adjacent closes, had been added; and the town then measured nearly half a mile every way, exclusive of the Canongate, which alao must have been advancing in density and space.

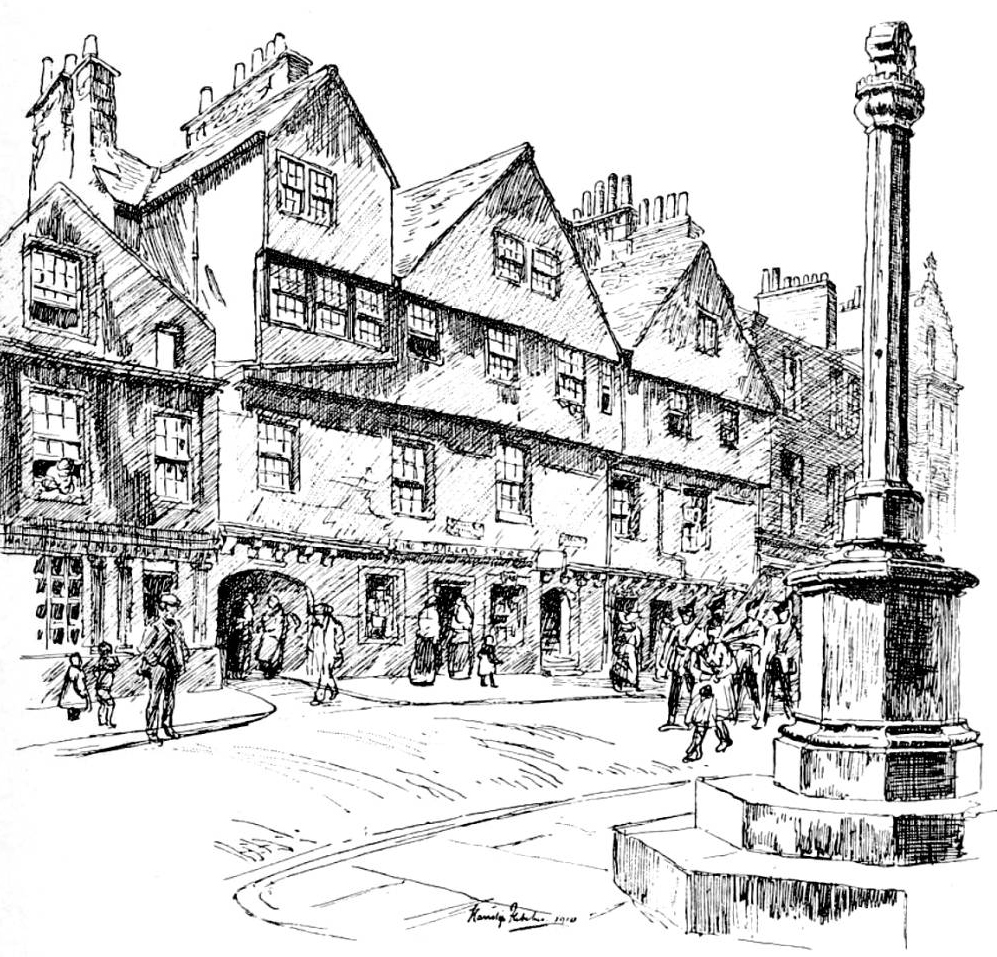

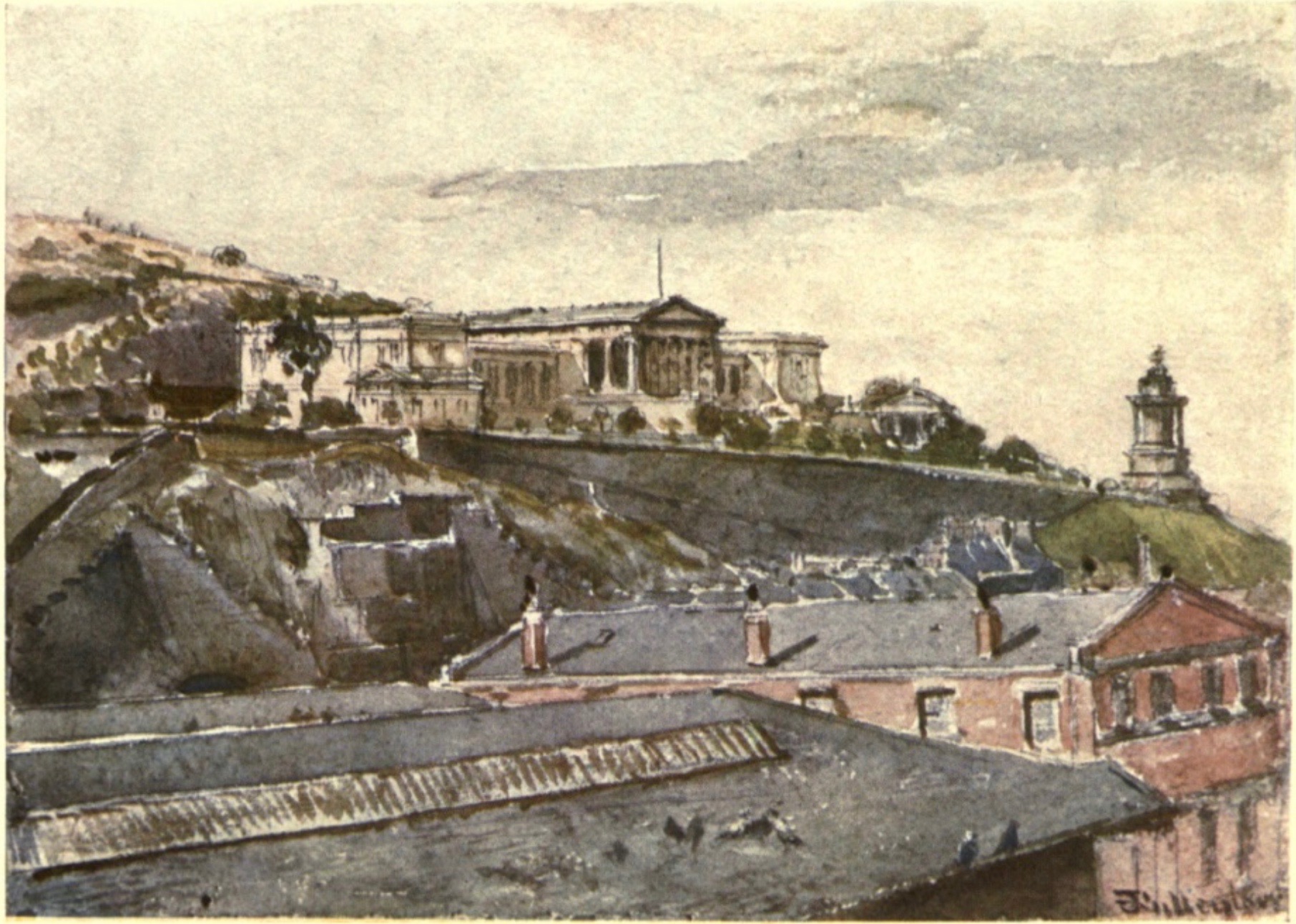

Old Houses in Canongate by John Fulleylove, RI. (1907). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The cause of this sudden start in the prosperity and extent of the town may be traced to the favour of royalty, which began to be showered more particularly upon Edinburgh after the murder of James I. at Perth. This is the era of its acquiring a metropolitan character — the time when parliaments began to be regularly held in it — the time when a royal palace was first built at Holyrood. Now also was the parishchurch of Edinburgh rendered collegiate; now were its artizans incorporated. Judging from a document given elsewhere, its streets by day must have been one universal market. At the same time, from the imperfect notions of the people as to cleanliness, dunghills must have contended for place with the most valuable merchandise, and stacks of wood, peat, and other fuel rendered the passage along the street as difficult and devious as walking in a farmyard.

The Third Stage of Street Architecture

The third stage of street architecture in Edinburgh presents us with stone buildings of three or four stories. Of this sort was the Black Turnpike, a fine old house formerly existing near the Tron Church; and which was believed to have been erected in the reign of King James II. (1437-60). But it is not to be supposed that buildings of this order were common in Edinburgh at that period. It is rather to be imagined that they were very rare. At least, it is certain, from a particular circumstance, that houses having wooden galleries in the front of the second storey were common in the very centre of the town, anno 1513. In that year, very shortly before the battle of Flodden, we are told by Lindsay of Pitscottie that Mr. Richard Lawson, provost of Edinburgh, was walking by night in his gallery opposite the Cross, to enjoy the air, when he saw the well-known apparitional ceremony of a proclamation, by which it is supposed some patriotic spirits endeavoured to frighten the king from his intended expedition into England. But even at this day there are some specimens of such houses existing in Edinburgh. One in every respect similar, but perhaps raised to a greater height, stands third from the head of the North Bridge, reckoning down the High Street. The celebrated rows of Chester are constructed upon the same principle, though different in so far as the galleries extend in an open way along a whole street, and are much wider. Whether of stone or wood, the houses in the High Street of Edinburgh would appear, from Sir David Lindsay's poem on the pageant of Queen Magdalene's public entry in 1537, to have then been composed of goodly buildings, which the inhabitants were able, on occasions of ceremonial rejoicing, to garnish with tapestry. Nor were the houses of the front street more elegant than those behind, for it is understood that the closes were then inhabited chiefly by noblemen, gentlemen, and persons unconnected with business, while the others were the residence of tradesmen and merchants.

It would be difficult, however, to state any particular kind of building as predominating at this period. The truth is, various orders of building must have now been mixed up together. There would here and there be seen the low-roofed tenement of the thirteenth century, surviving all its immediate neighbours while close by its sides might spring up the tall edifices of wood or stone, which had successively come into fashion at more recent periods. It must be mentioned that a very general variety, at this period, consisted in having piazzas below, wherein merchandise was exposed; of such there are examples still existing in the High Street, near the Fountain Well. A remarkable peculiarity, arising from the custom of projecting houses seven feet farther into the street, as noticed in an earlier part of this article, must also be noticed. The gates, with which most of the closes were shut up for protection from the tulyiers and spulziers of those times, were, in all cases, seven feet within the mouth of the close, having been so left at the time of the projection. Many traces of this may be seen at the present day, for, though the gates exist no longer, the gate-ways and the hooks for the hinges have been mostly left undisturbed.

Another peculiarity was the prevalence of outer stairs. These led up to the gallery in the second storey in the wooden houses, or a door-way in those of stone, and a spiral stair ascended within to the remaining flats. The people stood on these stairs to see processions. A historian of Queen Mary's time, tells us that, when that unfortunate lady was brought along the street, after being taken into the keeping of the confederate lords at Carberry, the women stood on these stairs, and reviled her with vulgar abuse, in reference to her late infamous marriage. Some of them yet remain, and are a decided nuisance, from the obstruction they give to people passing along the pavement.

Several houses yet exist in the Old Town, bearing date from the reign of Queen Mary; but are not remarkable for elegance of appearance. We find several, however, of the reign of King James, which present a massive and dignified aspect, being built entirely of polished stone, and rising to a great height. These houses, also, possess as good interior accommodation as any in the same district of the town, of whatever age. In many cases, the rooms are panelled, the ceilings decorated with plaster figures, and the door-ways ornamented with mouldings, not to speak of the quotations from scripture which so universally distinguish the architraves.

A house in the Canongate, built (as we should suppose) at the beginning of the seventeenth century, for the family of the Earl of Moray, and commonly, though erroneously, called the "Regent Murray's House," is a most respectable specimen of the taste of the time. We now find, moreover, that travellers who happened to visit the town, speak of the houses on the main street as singularly tall and elegant. In De Witt's bird's eye view of the town, taken at the middle oi the seventeenth century, we have a portraiture of the north side of the street, which certaiidy answers to this description. Some houses built in the main street during the reign of King William III. are in a style which has never been surpassed in the Old Town; we would instance — if the reader will excuse such minute detail — the building opposite to the head of the West Bow, and Gavinloch's land in the Lawnmarket. James's Court, built in 1728, is an excellent specimen of the taste of a succeeding generation.

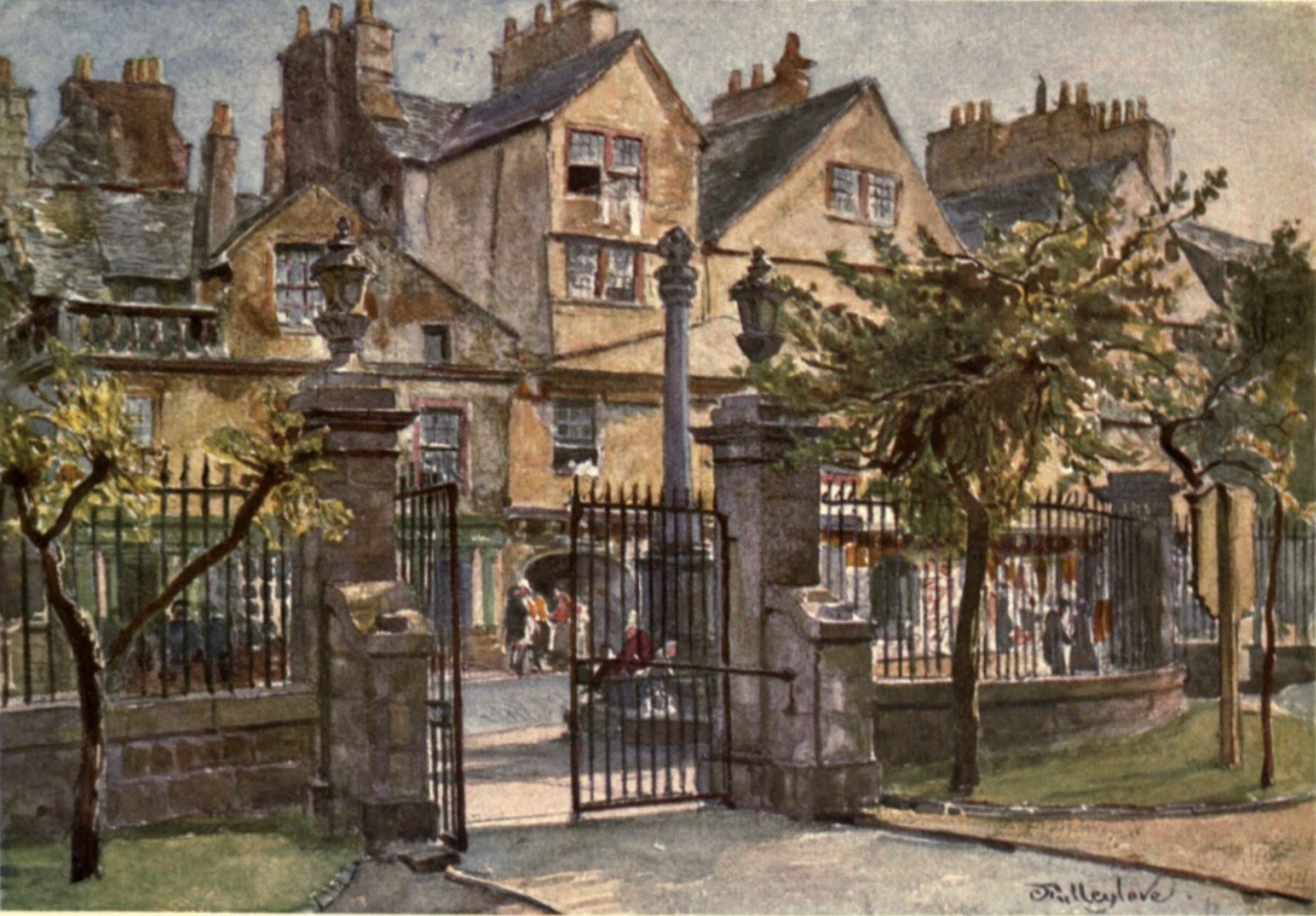

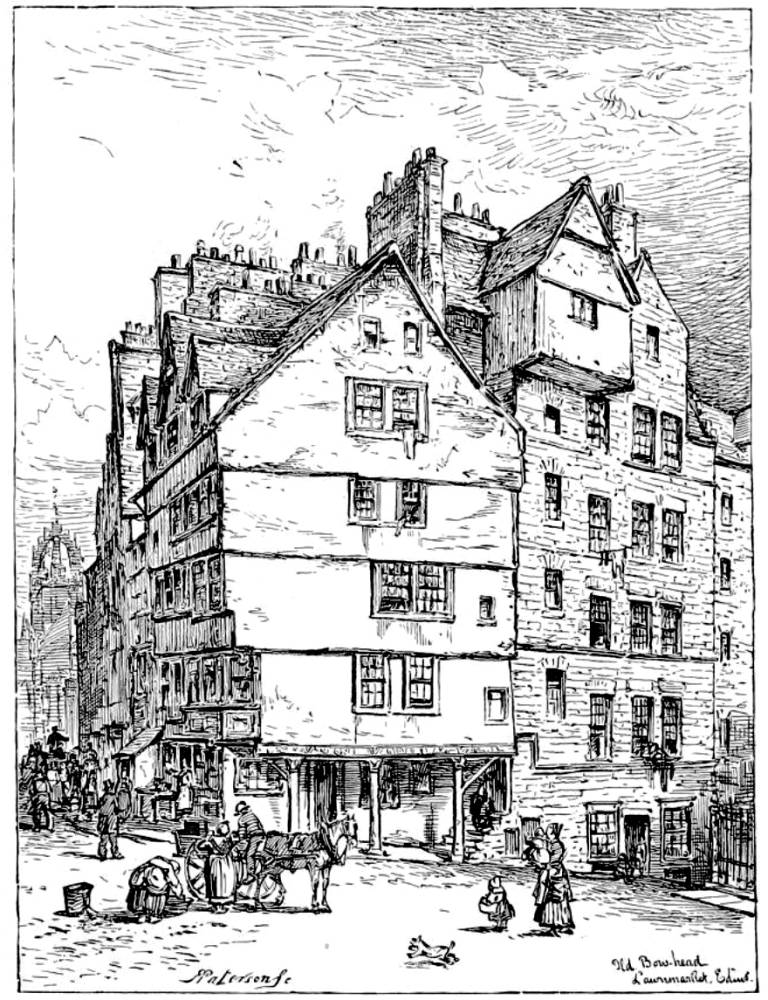

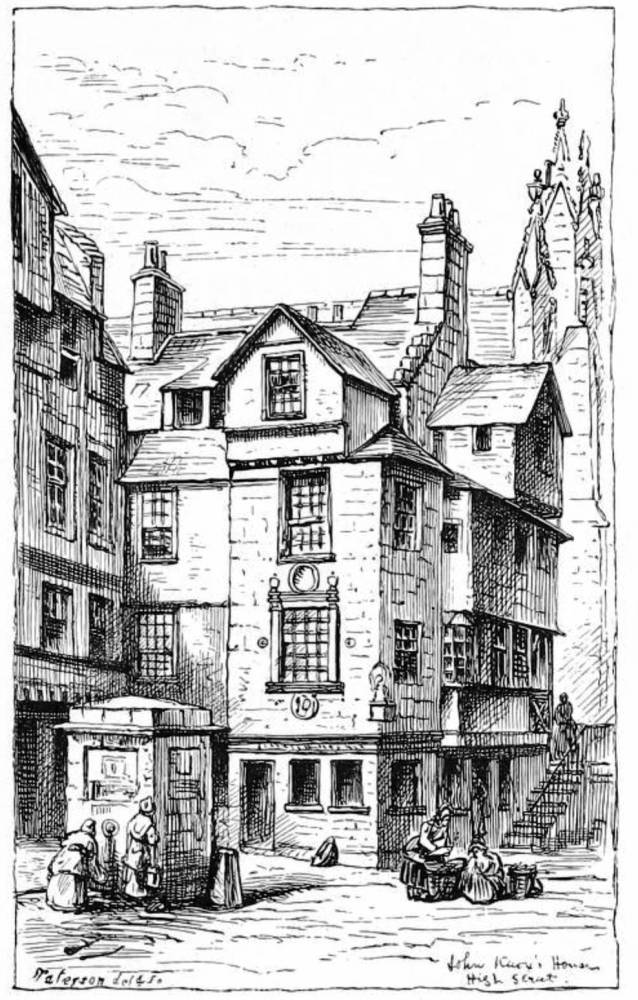

Old Bow-Head, Lawnmarket from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh. Click on image to enlarge it.

Up till the middle of the eighteenth century, Edinburgh continued to occupy little more than the same space of ground which it had assumed in the reigns of James III. and IV. Its external appearance was grand, and travellers invariably admired the lofty magnificence of its principal street. Yet the details were often mean, confined, and squalid; and wealth could not find either the elegance, or the space which it so imperatively requires.* be necessary. In short, that era in the prosperity of the country had now arrived, when men could no longer put up with the merely decent and comfortable accommodations, nor with that commixture of all ranks, which satisfied their fathers, hut demanded residences that might- be at once more elegant and more exclusively their own.

It may easily be supposed, that where so extensive and decisive an alteration was projected, as the erection of a separate city by the side of that already existing, there must have been many difficulties to overcome, not only in the arrangements preparatory to building, but in the process of reducing the fears of that large portion of the community, who, in all such projects, think it necessary to be timid upon principle, and even fear after all danger is past. The chief difficulties in the undertaking lay in the necessity of commencing the proceedings by building a long and lofty bridge, to connect the existing and the contemplated districts, in the necessity of procuring the consent of the neighbouring interests, some of which had serious scruples touching self, and in the necessity of obtaining an act of parliament, to extend the jurisdiction and taxing power of the city over the ground proposed to be built upon. After twelve years of fruitless agitation, the enterprising Provost Drammond resolved to take the first step at every hazard, and, accordingly, on the 21st of October 1763, he laid the foundation of what is now styled the North Bridge, veiling it so far to the rejudices of lesser minds as to style it merely a convenience for the purpose of opening up an improved road to Leith. In 1767, while this work was proceeding, an act for extending the royalty was obtained, during the provostship of Gilbert Laurie, Esq. and, a plan for the new city being then formed by Mr. Craig, architect, (nephew of Thomson, the poet,) tha first house was founded on the 26th of October.

Unfortunately for the success of this magnificent undertaking, it had no sooner overcome obstacles of one description, than it encountered greater ones of another. During the long delay which took place between its first projection and the building of the bridge, another New Town had taken occasion to spring up in an opposite quarter, which, neither requiring an act of Parliament, nor the unanimity of a set of interested proprietors, to bring it to maturity, soon gathered force sufficient to counteract the immediate success of the northern extension. This might have been happily prevented, had the magistrates had the foresight to buy up a piece of ground south of the city, which was offered to them for £1200. It was purchased by a builder, named James Brown, a most enterprising individual, who immediately prepared to erect houses upon it, of suitable elegance to meet the rising taste for fine mansions — an undertaking which found all the success it deserved, in the favour of a certain class of the higher orders, several years before a single stone was laid of the extended royalty. The magistrates soon repented of their neglect; and offered Mr. Brown £2000 for the ground; but he, being now well aware of the goodness of his bargain, demanded £ 20,000, and the consequence was, that the city-rulers in despair suffered him to go on. Brown's Square, (named after the builder,) was therefore soon finished and filled with respectable in* habitants, and George's Square lying more to the south, became still more attractive than its predecessor, on account, perhaps, of its greater distance from the Old Town, and the superior style, both as to size and accommodation, in which most of the houses were executed. The inhabitants of these southern districts formed, about fifty years since, a distinct class, and had their own places of polite amusement, independent of the rest of Edinburgh. The society was of the first description, including most of the members of the mirror club, (consisting of Mr. Mackenzie, author of " the. Man of Feeling," Lord Craig, Lord Abercrombie, Lord Bannatyne, Lord Cuilen, Mr. John Home, author of " Douglas," and Mr. George Ogilvie,) and many other characters of high eminence in the law and in fashion.

Nearly coeval with Brown and George's Squares, and another rival to the New Town, was St. John's Street, proceeding southward from the Canongate, which was also inhabited by people of the highest respectability. New Street, at no great distance, on the north side of the Canongate, was another of the rival streets which anticipated, and served to retard, the rise of the New Town. Among other dignified inhabitants, it possessed Lords Hailes and Karnes, both eminent in the history of Scottish literature. Argyle Square, contiguous to Brown Square, is understood to have grown up at a fully earlier period than the neighbouring modern erections, part of it being formed even so early as 1742. Another southern contemporary of the New Town was Adam's Square, a short way east of Argyle Square and now forming a part of South Bridge Street. All the houses of this square were originally occupied by distinguished personages, among whom were Lord ' Gray, Lord President Dundas, Lord Forbes, and Lord Dreghorn. *

After the New Town had been fairly begun, it had to encounter many obstructions. The bridge, which was not in reality commenced till May 1767, had proceeded near to completion, when, August 3, 1 769, the vaults and side-walls at the south end gave way, and buried five persons in the ruins. Even after it was made passable, in 1 772, it was found a cold and dreary walk, and people shivered at the very idea of leaving the smoky warmth of the old town, to locate upon the bare exposed fields to the north, where only, as yet, one house here, and another there, testified the enterprise of the builders of the day, or the craze (as it was thought,) of a few private individuals of peculiar taste. In addition to all, the magistrates, by an act of unprincipled meanness, such as no men in the present day would ever think of attempting, disgusted the public at their own plan, by erecting a series of low buildings (still standing under the name of Canal Street, &c.) close to the new town, where the feuars of the ground had been led to expect a beautiful range of hanging terraces and an artificial canal. Yet, in spite of all difficulties, the plan did in time proceed. Be tween the years 1767 and 1780, it had extended over nearly a third of ground designed for it, comprehending a part of Prince's Street, St. Andrews Square, St. David Street, a part of George Street, and even some few houses in Hanover Street. The architecture, we must confess, was much inferior to what we have since seen in the more westerly and northerly districts. In many cases, it was even under the standard of the Old Town. Yet, when we consider that the houses, instead of being divided into flats, were what is called selfcontained, and thus afforded a great deal of additional accommodation and elegance, it must be allowed that the improvement was altogether very much to be admired. That it was appreciated in this light by men of cultivated minds, is proved by Arnot's declaring, in his history, (1776) that St. Andrew's Square was "the finest square he ever saw."

Old Bow-Head, Lawnmarket from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh. Click on image to enlarge it.

The erection of so many buildings on the fields south of the Old Town soon suggested the necessity of a proper communication between them and the High Street, on the plan of the North Bridge, and in 1775, a proposal was made for erecting a bridge over the valley to the south. Hitherto, and till this scheme was executed, the line of the south side of the High Street remained unbroken from the entry of the Parliament Square to the Netherbow Port, and exhibited an outline of very high, and in many cases, magnificent houses. The only access to the fields and new squares on the south was by the different closes, one of which, somewhat wider than the rest, opposite the opening of the North Bridge, called Merlin's Wynd, was the principal thoroughfare. It led off the High Street on the east side of the Tron Church, at the back of which it turned westward and then pursued a direction down to the Cowgate on nearly the present site of Blair Street. Half way down this incommodious thoroughfare, on the east side, there was an open poultry market. While the High Street continued thus closed up on its south side, the only entry to the town for carriages was either by the narrow and steep defile of the West Bow, or the passage through the mean suburban streets of the Pleasance and St. Mary's Wynd, to the head of the Canongate. The construction of a bridge and fine of ctreet towards the south became, therefore, a work almost of necessity, and an act of parliament having been procured, which included this improvement, the foundation-stone of the South Bridge was laid on the 1st of August, 1785, and the thoroughfare was opened for passengers in March 1 788. The South Bridge consists of twenty-two arches, all of which are concealed by the buildings along its sides, with the exception of one near the centre, which has been left open on account of the Cowgate. The magistrates having purchased the ground from the proprietors, sold it out to builders at most incredibly high prices, which, in some eases, amounted to the rate of £ 150,000 per acre. The buildings erected on South Bridge Street, were finished in a very tasteful manner, in a very short space of time, and having been constructed for shops on the ground floors, till this day the street exhibits a much more business-like appearance than any other modern street in the metropolis. As soon as the line of South Bridge Street was completed, which was in direct continuation'' of North Bridge Street, an easy thoroughfare was at once obtained from the country on the south through the Old Town to the New Town, and on the southern parks different new streets were erected, though generally in an inferior style of building. The principal street, so reared, was Nicolson Street, with Nicolson Square, both taking their names from a Sir John Nicolson, the proprietor of the ground. The improvements in this quarter were hastened in 1789, by the founding of the splendid new university buildings, which were begun on the site of the old college, and on the west side of South Bridge Street. To proceed with our description of the extension of the New Town: By the plan laid down by Mr. Craig, the chief streets of the New Town, were disposed in simply three parallel lines from east to west —that on the south side, formed with only one side, like a terrace facing the Old Town, called Prince's Street; a similar street on the north, looking towards the sea, called Queen Street; and the third, which was named George Street, running up the centre. An elegant square at the west end of the latter, styled Charlotte Square, balanced another at its eastern termination, designated St. Andrew's Square. Between Prince's Street and George Street, a narrow street of inferior houses, ran the whole length, and a street nearly of the same appearance, was situated betwixt Queen Street and George Street. Seven cross streets intersecting the whole of these parallel thoroughfares, completed the plan. In recent times the discovery of which was the very first house built in the New Town, has become an object of reasonable curiosity, and it is wonderful how much doubt prevails upon this point. The difficulty of making this discovery has been considerably increased by the circumstance, that at least two houses were built before the act of parliament for the extension was procured, and consequently not included in the plan. One of these is at the north-east back of James Square, and the other in Rose Court, behind St. Andrew's Church. One of the first houses built after the plan was arranged, was the corner tenement at the south-western extremity of South St. Andrew's Street. It was built by the father of the late Sir William Forbes, who removed to it from Carrubber's Close; and here was born Sir "William, who we believe, was one of the first natives, (if not the very first) of the New Town. Several tenements further west, in the line of Prince's Street, adjacent to St. David Street, are also among the oldest in the New Town. The first edifice for which ground was found, was that beautiful tenement immediately west from the General Register House. The purchaser of the feu was Mr. John Neale, a silk mercer in the Old Town, who is otherwise remarkable, as having been the first tradesman in Edinburgh who assumed the phrase of Haberdasher as a description of his profession. He tried without success, to establish a shop in the premises, about the year 1774, and it was not till towards the period of 1790, when the New Town had extended over a good deal of ground, so as to render Prince's Street a considerable thoroughfare, that the few shops there opened conld be considered so prosperous as those in the more central parts of the Old Town. In consideration of the priority of erection of the house of Mr. Neale, the magistrates decreed that it should for ever be free of burgal taxes, and till this day the tenant or proprietor is unburdened by any cess or impost.

While the first houses were in the course of erection, a building for a Theatre-Royal was founded in 1768, at the north end of the North Bridge on its east side, and the house was opened on Wednesday, the 9th of December, 1769, since which period it has continued to be the only theatre in Edinburgh for what is called the legitimate drama.

One serious and irremediable error committed by the magistrates of Edinburgh, in connexion with the building of the New Town, remains to be mentioned. We refer to the Earthen Mound. This is a vast mass of earth which has been laid down in the vale of the North Loch, betwixt the Old and New Town, and calculated to serve the purpose of a bridge. The raising of such a huge mound of rubbish originated in the following accidental circumstances: About the year 1781, when the building of the New Town had extended westwards about as far as Hanover Street, some shopkeepers in the Lawnmarket and Castlehill, (the upper parts of the main street in the Old Town,) who were in the habit of frequently visiting the opposite bank of the North Loch, in order to observe the progress of the buildings, finding it inconvenient to go round by the North Bridge, fell upon the expedient of laying a few planks upon the marshy bottom of the intermediate valley, over which they could pass dry-shod and reach the object of their curiosity at about one-third of the expense of travel. This measure was chiefly promoted by Mr. George Boyd, a public-spirited dealer in tartan cloths. The passage was soon after rendered firmer and more agreeable by some loose earth accidentally thrown out from a quarry which it was attempted to excavate at this spot on the north bank of the Loch, and this was the means of suggesting to the consideration of many, that if the earth dug from the foundations of the buildings in the New Town were deposited here, the convenience of the builders would not be lost sight of, while the advantage of a new bridge woidd be supplied to the public generally at no expense. Upon a representation, therefore, made to the magistrates by the inhabitants of the Lawnmarket and Castlehill, it was decreed in November 1782, by the town-council, that all rubbish, &c. should be brought to this spot, whereby, in the course of a very few years, the mass was raised to the required height, and became such a thoroughfare, that it was at length found necessary to open up the passage of Bank Street, in order to admit carriages, the passage from and into the Old Town having as yet been only by closes. It was very remarkable and not a little ludicrous, that by this destruction of the ancient street, Mr. Boyd, the original projector of the Earthen Mound, had the mortification to see his own house demolished; aid as if the public were determined to render him no thanks whatever for his suggestion, the original name of Geordie Boyd's Brig, has been for many years lost and unknown. From the year 1781 till the year 1830, the Earthen Mound continued to be augmented by the regular or occasional deposition of rubbish, and it is now in a state of something like completion, being levelled and Macadamized on the top, sown with grass on the sides, and otherwise embellished. It measures several hundred feet in all directions, and is computed to contain upwards of two millions of cart loads. The low grounds to the east and west of the Earthen Mound continued for about fifty years after the commencement of the New Town in a very marshy and profitless condition. At length in 1821, under the authority of an act of parliament, the ground on the west was enclosed, drained, planted with trees, shrubs, and flowers, and walks formed, winding round the bottom of the castle rocks and the sloping banks on each side. This pleasure-ground is only open to the proprietors or tenants of houses in Prince's Street, or others, who are furnished with keys on paying certain sums annually. The ground to the east of the Mound is now in course of being enclosed and ornamented in a similar manner. Still further to the east are the town slaughterhouses and markets.

The Second New Town.

Such was the ultimate success attending the building of the New Town of Edinburgh, that, in time, a Second New Town was projected still further to the north, and the plan being supported by an act of parliament, its erection forthwith took place. The design of this second town intimately resembled that of its predecessor; consisting of a terrace in front and in rear, a large central street, with two intermediate narrow ones, and cross streets, in continuation of those in the former New Town. This vast and splendid addition to Edinburgh was commenced in the year 1801, and, with minute exceptions, was finished in 1826. The space betwixt Queen Street, and the southern terrace of the Second New Town, which bears the various names of Heriot Row and Abercromby Place, is disposed in pleasure-grounds, under the proprietory of the adjacent house proprietors, in virtue of acts of parliament. Taking this series of gardens in connexion with the pleasure-grounds formed in the bed of the North Loch, it may be pronounced one of the most beautiful, and also most useful points of modern Edinburgh. The grounds being laid out in walks, which are accessible to the adjacent inhabitants, one of the great disadvantages of a town residence has in some measure been overcome, as the enjoyments of a park and garden can here be had as well as in the country. At the same time, the space left free, in the very centre of the town, for the circulation of fresh air, cannot fail to have the most beneficial effect in regard to the general health. Indeed, both as to convenience, salubrity, and ornament, these gardens form a characteristic feature such as is presented by hardly any other town in Europe.

The central street of the Second New Town, corresponding to George Street in the First, is entitled Great King Street, and is a most elegant collection of buildings. As in the case of George Street, it is terminated by large open areas: one of these is of an oblong or parallelogrammatic form, and is styled Drummond Place; the other is of a circular shape, and is called the Royal Circus. Within the open area of Drummond Place, stands the Excise Office, an elegant house originally built for a residence by General Scott, (father-in-law of Mr. Canning), and styled Bellevue, but afterwards occupied, first as a Custom House, and then in its present capacity. It is worthy of remark that Provost Drummond, who was mainly instrumental in overcoming the difficulties that obstructed the commencement of the New Town, has had no other memorial in reference to that splendid public service, than the name of this square. We have even been assured, that but for an accidental suggestion of the late Commissioner Jackson (of Excise), who was present when a name for the place was under consideration, and remembered that the worthy magistrate had had a villa within its area, even this humble memorial would not have existed. So capricious a principle is public gratitude! It may be worth while to mention at this place, that Duke Street, Albany Street, and York Place, are named in honour of the Duke of York and Albany; Abercromby Place, Howe Street, St. Vincent Street, Nelson Street, &c. after other heroes of the war which raged at the time I when the plan was formed — Fettes Row in compliment to the then Provost of Edinburgh, and London Street, Dublin Street, India Street, and so forth, in reference to those places respectively. Moray Grounds, Sfc. — About the time when the Second New Town approached to completion, it began to be surmised that the next space of ground which was fitted to accommodate the ever-increasing population, was a park belonging to the Earl of Moray, lying between Charlotte Square and the Water of Leith, and bounded on the east by the district of town just described.

The Water of Leith from Dean Bridge by John Fulleylove, RI. (1907). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Accordingly, the noble proprietor having consented to grant feus, and a general plan having been prepared by Mr. Gillespie, the first spadeful of earth was taken out of the ground, for the foundations, on Christmas day 1822. In Spring 1823, 4, and 5, the work proceeded with a marvellous degree of rapidity, and even after that period, when the financial panic communicated a severe blow to building specidations in Edinburgh, the operations were not materially retarded. The plan, which had been hampered a good deal by the triangular figure of the ground, consisted chiefly in a spacious octagon at the east end, and a smaller oval towards the west, communicating with each other, and entered at various points from the neighbouring thoroughfares by other streets. The houses were reared in the most magnificent style, after the general plan, and were readily purchased and leased by persons of the first style of living in Edinburgh. The various squares, streets, and places, are styled after the family name, titles, and mansions of the noble proprietor of the ground. In the neighbourhood of this district, to the south-west, is a series of beautiful streets, chiefly erected upon the parks that formerly enclosed a seat called the Coates. One, which may be said to continue the line of George Street, is called Melville Street, and is composed of most elegant buildings. There are also two splendid crescents, facing each other across the Glasgow Road, and of which the architectural plan is extremely beautiful. They are respectively styled Athole and Coates Crescent, the latter being adorned by a row of trees conforming to its own shape. As it is by this route that nearly all persons from the west of Scotland enter the town, the appearance of so many structures on a scale of uniform splendour, almost unrivalled in Britain, or perhaps the world, seldom fails to excite feelings of delight and admiration.

A very important undertaking is at present going on in this quarter of the New Town of Edinburgh. By the houses of the Moray grounds having been placed on the verge of the ravine through which flows the Water of Leith, no farther extension of the city could possibly be made in a north-westerly direction, unless by the erection of a bridge across the dell, to give access to the fields on the opposite side of the river. Such, therefore, is now in the course of formation. A most stupendous bridge of four arches is in the course of erection, which, when finished, will be unequalled in height in this part of Scotland, and will afford a delightful prospect down the romantic vale of the Leith. It will connect Queensferry Street, or the road leading northwards from the west end of Prince's Street, with the extensive parks on the north side of the water, feued by certain enterprising builders, who design to lay them out after a novel and most felicitous plan, whereby it is provided, that each house shall be distinct from its neighbours, and surrounded entirely by a certain extent of pleasure-grounds and shrubberies, throughout which the whole are interspersed. At present these fields decline with a gentle slope northwards to the populous suburb of Stockb ridge, and are already partly covered with handsome houses near the river.

The Eastern New Town

While the above mentioned improvements were in the course of execution, the extension of the city to the east of the New Town went on very slowly, and for many years the road to Leith by Leith Walk remained in a wretched condition. Active measures were, however, adopted to remodel "the Walk," which has been done at a prodigious expense, liquidated by a tollbar. This way, which is altogether paved, and is more than a mile in length, is now one of the most noble thoroughfares in the world, being perhaps only surpassed by the Broadway of New York, to which it has not inaptly been compared. It is lined with nursery grounds on each side, partly built upon; and on its east side, betwixt the Calton Hill and the environs of Leith, the rudiments of a city, not less splendid than those just mentioned, have at present been formed. A superb terrace of houses, encircling the Calton Hill, half way up its sides, and overlooking this tract of ground, is nearly finished, which on its southern quarter joins the New London Road, which traverses this conspicuous eminence.

Calton Hill Improvements, and Eastern Approach

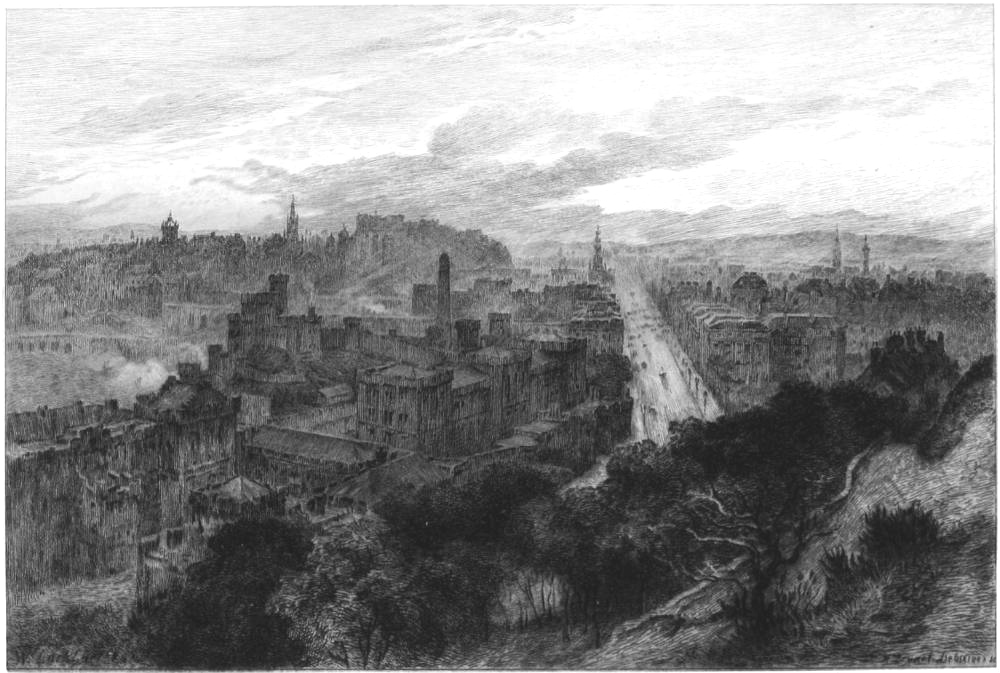

The View from Calton Hill Etching by A. Brunet-Debaines from a drawing by W. E. Lockhart, R.S.A. 1879. Source: Stevenson, Edinburgh. Click on image to enlarge it.

A notice of this road leads to the description of a distinct "Improvement" of the capital not yet mentioned. From about the date of the erection of the building of the first New Town, till the year 1814, Prince's Street was closed up at its east end, (with the exception of a thoroughfare down Leith Street, still remaining,) by a cross line of houses," composing part of Shakespeare Square, the back of which overlooked the ravine of the Low Calton, and the Calton Hill beyond. These tenements were of a respectable order, and while the upper flats were used mostly as lodging-houses, the lower were occupied as shops and taverns. About the middle, facing up the centre of Prince's Street, was the Shakespeare Tavern and Coffee House, which for many years was the most respectable establishment of the kind in Edinburgh.* [* For the purpose of rendering this house the resort of the elite only, its owners instituted a regulation that none should be admitted but those having white neckcloths, a law which they had to rescind in the latter days of the establishment— but the head-waiter always appeared in full dress] The population of the New Town and thoroughfare of passengers and carriages to and from Prince's Street having greatly increased, a serious inconvenience was felt from the want of a proper communication with the east country, and it was remarked that no entrance could be obtained so conveniently as by the removal of the houses of Shakespeare Square, and the throwing of abridge across the hollow to the Calton Hill, along which a road might proceed eastwards. Under the special patronage of Sir John Marjoribanks of Lees, Bart. M. P. thenLord Provost, an act of parliament, for the fulfilment of this scheme, was passed in 1814. The foundation-stone of the bridge, which was styledRegent Bridge, was laid on the 19th of September 1815, and the work was completed in March 1819. The arch over the Low Calton is fifty feet wide, by about the same height. On the top of the ledges of the bridge, are ornamental pillars and arches of the Corinthian order, which on each side are connected with the houses in the line of street, formed at the same time. The street, or Waterloo Place, as it has been designated, is composed of very superb houses of four stories, and each range is terminated at Prince's Street by a pediment and pillars above the lower storey. On the south side lire the Stamp Office and General Post Office, both buildings of the best kind of Grecian architecture, but no way superior in appearance to the houses adjoining. Opposite the Post Office, a large tenement was built at an expense of about £ 30,000, to suit the business of a Hotel and Tavern, but this establishment, (the Waterloo,) which is in the proprietory of a joint stock company, has not succeeded, and is now closed. It contains two large rooms, eighty feet by forty, which are often used for public meetings, and the lower is fitted up as a reading room.

From "Waterloo Place, the new road, by which the London Mail, find most of the coaches from the east country enter the city, proceeds, by a sweep, round the south face of the Calton Hill, and joins the old road which enters by the Canongate, near Piershill Barracks, about a mile to the east. The entry to Edinburgh, by this thoroughfare, is not less commanding and beautiful than that by the west, and, in some respects, it is superior in point of interest, as the stranger is surprised with the antique grandeur of the Old Town, before the long vista of Prince's Street opens on his view. In entering from the east, the stranger passes through a series of splendid erections, and, on his right, on the summit of the hill, stand several monumental edifices, all of which are noticed in their appropriate places; meanwhile we proceed with an account of the alterations and extensions of the city.

Canal Basin, and Improvements on the Southwest

The formation of a navigable canal betwixt Edinburgh and the Forth and Clyde Canal, near its embouchure into the River Forth, by which the metropolis might be connected by water with the city of Glasgow, was a project contemplated many years ago, but, for different reasons, could not be carried into execution till the year 1817, when an act of parliament was procured by a joint stock company, and the line was finished in May 1822. The chief objects of such an institution were the transport of heavy goods to and from Glasgow, and the import of coal into Edinburgh from the western districts, as well as the export of manure, all of which have been completely attained, to the great profit of the community, but unfortunately, to the serious loss of the shareholders. The eastern termination of the Union Canal, as it is termed, is at a level spot of ground about half a mile south-west of the castle, where its introduction has utterly revolutionized the appearance of the district. About sixty years since, almost the only houses in this quarter were a series of dwellings along the line of road proceeding westwards from the Grassmarket and Wester Portsburgh, entitled Fountainbridge. These edifices, as may yet be seen from some of their desecrated remains, were what were termed English houses, being built in the style of comfortable villas, and inhabited principally by English residents, who had official situations in Edinburgh, and more particularly in the Excise Office, then situated in the Cowgate. Until the cutting of the Canal commenced, this was a pleasant rural suburb of Edinburgh, though greatly fallen from its former condition; but the formation of the basin or harbour for vessels altogether altered its character. This spacious basin, which has been styled Port Hopetoun, is now immediately environed by offices for the sale of coal, by wharfs and other accessaries of commerce, and beyond the quay it is surrounded by handsome streets, leading in different directions. The access to the west end of the New Town is secured by a street, only partly built, called the Lothian Road; but hitherto the only direct communication with the High Street has been by way of the Grassmarket and West Bow. In 1825, the last mentioned street being nearly inaccessible to carts, so as to isolate, in some measure, both the High Street and the Canal suburb, the propriety of a communication, which should throw open the Old Town to the western districts, became keenly agitated, and at last resolved upon. Along with this "improvement," it was resolved to lay down a similar road and bridge, which should lead from a point further down the Lawnmarket, across the Cowgate, thus opening up the Old Town to a free ingress from the south. An act of parliament having been procured, sanctioning the measures and giving power to a body of commissioners to assess the inhabitants for the expense, the work of destroying old houses, and building the bridges, was simultaneously commenced. By mismanagement, or want of just calculation, the funds for carrying such an extensive improvement into effect have failed, and at present, (February 1831,) while the town is agitated regarding the removal or extension of the assessments, a great part of the environs to the west and south remain in all the confusion of old ruins and new half-built erections. When completed, these lines of way into the old city will be of incalculable advantage in restoring the bustle of traffic and a concourse of passengers to the ancient part of the metropolis. The line of the western approach leaves a point near Port-Hopetoun, and is carried over the hollow ground on the south side of the castle rock by a single arch, from whence it proceeds along the face of the castle bank to the head of the Lawnmarket. It is intended to be partly lined with houses on each side. The line of the southern approach leaves the high ground at Bristo Port, and is carried across the vale of the Cowgate by seven side and three central and visible arches, at a spot about three hundred yards west of the former South Bridge, and enters the Lawnmarket at a point opposite Bank Street, a thoroughfare leading by way of the Earthen Mound into the New Town.*

By a ridiculous arrangement, it has been determined that the West Bridge shall be styled the King's Bridge, while the South is to be termed King George IV.'s Bridge; and these epithets have been sanctioned by the approbation of his late Majesty, to whom both were designed to be complimentary. Such a betise is enough to render the character of King George IV. as a man of taste a matter of doubt to posterity. The Castle or West Bridge, and the Cowgate or Lawnmarket Bridge, are the obviously proper designations, and some of these will certainly be adopted by the public, while the royal titles must clearly sink into oblivion. As the street of the Cowgate Bridge passes almost close by the back of the Parliament House, we suggest that it be named Parliament Street. It is proposed to erect private houses with shops on part of this line, and fill up the remaining space with public edifices. Among other improvements to be made simultaneously with these, is the lowering of the surface of the Castlehill Street, the Lawnmarket, and High Street, to the depth, in some places, of about twelve feet

Alterations on the Old Town,- the Cross.

In the course of the improvements effected on Edinburgh, various alterations were made on the Old Town, which, though perhaps required by some narrow views of expediency, were certainly not directed by good taste. The first of the antique objects which suffered, was the Cross, an octagonal building, surmounted by a pillar, which rose upon the south side of the High Street, a little below St. Giles. The Cross had been used for many ages not only in the common duties of a burgh market-cross, but for many purposes connected with the state and the legislature. In early times, before the art of printing was known, acts of parliament were here read out to the people. Royal proclamations were also made here. We have already mentioned the fact, recorded by Pitscottie, that, before the Scottish army had marched to Flodden, a visionary proclamation, in imitation of those which were sanctioned by royal authority, was issued at night on this spot, to deter the people from the expedition. From the wars which followed Queen Mary's resignation in 1567 to the Re volution of 1688, this was the principal place for executing the numerous victims of civil dissension. It appears that during the turbulent minority of James VI., a gibbet stood constantly ready on the spot for nearly twenty years, till at length it was cut down amidst the rejoicings which attended a general reconciliation of the nobility brought about by his means. The Cross, moreover, was the chief scene of all public rejoicings, was honoured with the principal pageants at the entries of sovereigns, and formed the ground-work of a platform when the magistrates used to drink the king's health on his birth-day. Distinguished in all these ways, the centre of business, the place "where merchants most did congregate" it was altogether one of the most interesting objects m Edinburgh. Unfortunately, in 1756, when the Royal Exchange was finished, the magistrates conceiving that it could no longer be necessary as a rallying point or rendezvous for commercial people, and thinking, moreover, that it encumbered the street, caused it to be demolished, leaving only a radiated pavement to mark the space of ground which it had occupied.

The historians of Edinburgh, Grose included, seem to have been unacquainted with any dates connected with the history of the Cross. We find one in Calderwood's Larger History, (MS.? Advocates Library} which refers the building, exclusive of the pillar, to 1617, when it was substituted, for one previously existing. The following is the passage.

"Upon the twenty-six of February, the Cross of Edinburgh was taken down. The old long stone, about forty footes or thereby in length, was to be translated by the devise of certain mariners in Leith, from the place where it had stood past the memory of man, to a place beneath in the High Street, without any harm to the stone; and the body of the old Cross was demolished, and another builded, whereupon the long stone or obelisk was erected and set up, on the 25th day of March."

The Cross is thus described by Amot: —

"The building was an octagon of sixteen feet diameter, and about fifteen feet high, besides the pillar in the centre. At each angle there was an Ionic pillar, from the top of which a species of Gothic bastion projected; and between the columns there were modern arches. Upon the top of the arch fronting the Netherbow, the town's arms were cut, in the shape of a medallion, in rude workmanship. Over the other arches, heads also cut in the shape of a medallion, were placed. These appeared to have been of much older workmanship than the town's arms, or any other part of the cross. The heads were in alto relievo, of good engraving, but the Gothic barbarity of the figures themselves bore the appearance of the Lower Empire. One of the heads was armed with a casque; another with a wreath, resembling a turban; a third had the hair turned upwards from the roots towards the occiput, whence the ends of the hair stood out like points. This figure had over its left shoulder a twisted staff, probably intended for a sceptre. The fourth was the head of a woman, with some folds of linen carelessly wrapped round it. The entry to this building was by a door fronting the Netherbow, which gave access to a stair in the inside, leading to a platform on the top of the building. From the platform rose a column, consisting of one stone, upwards of twenty feet high, and of eighteen inches diameter, spangled with thistles, and adorned with a Corinthian capital, upon the top of which was a unicorn."

On the removal of this beautiful structure, the four sculptured stones, above described, were secured by an eccentric gentleman, Walter Ross, Esq. of Stockbridge, and built into a sort of a tower, which he erected near his house, of stones procured from various old buildings, long known by the name of Ross' folly. On the destruction of the tower a few years ago, these stones were secured by Sir Walter Scott, and are now preserved at his seat of Abbotsford. The pillar, which was broken in the course of being taken down, still exists in the policy of Drum, a seat about four miles south from Edinburgh, the property of Gilbert Innes of Stow, Esq. The Netherbow Port. — This was another edifice of an ornamental character, which the magistrates thought it necessary to destroy for the sake of pubbc convenience. It served as a graceful termination to the High Street, where it joined the Canongate, and might have been termed the Temple-Bar of Edinburgh, as it served a similar purpose, in dividing a privileged from an unprivileged part of the town. It was a fine castellated building, surmounted by a tower and spire, in which was a clock, and pervious below by a large gateway and wicket. The date of the building was only of the reign of James VI.; but it is understood to have then been substituted for an older edifice, which might have perhaps been erected at the same time as the first city wal£ Upon the Netherbow was a spike of iron, upon which the heads of traitors and others were exhibited. In later times, when the walls and ports of Edinburgh could scarcely be considered as useful for a warlike purpose, we find Allan Ramsay giving an amusing account of the obstruction which the Netherbow Port presented to good fellows like himself, who, having got drunk in the Canongate, had to make their way home to town after the hour for locking die gates. In consequence of the affair of Captain Porteous, the House of Lords, in the first burst of indignation, ordained the Netherbow Port to be demolished, but, being pacified into a revocation of the order, this dignified edifice, with its gate, remained undisturbed till the time of the agitations created by the improvements. Under the impression that the passage was not wide enough for the thoroughfare (! ) and that the gateway could not be widened without injury to the building, it was pulled down in 1764, and nothing now remains to point out its locality. In old news of Edinburgh, the steeple of the Netherbow Port harmonizes finely with a similar spire at the head of the town, rising from the Weigh House; these two, with the intermediate spires of St. Giles and the Tron Church, gave the Old Town, under certain aspects, more the air of a city than it possesses at present. For some idle reason, which we have not been able to discover, the spire of the Weigh House was taken down, according to Amot, about a hundred years before the period he wrote (1776), and from that time till 1822, the body of the house only remained, a mass of deformity on the public street. The Weigh House stood detached from all other buildings, at the head of the West Bow, on a piece of ground which had been conferred upon the burgh by David II., in the year 1352. It consisted of two stories, the lower of which was used for weighing goods, while the upper was leased by a dealer in butter and cheese. As we have seen, James III., in 1477, ordained a Tron or pair of scales to be there set up, as public weights, for butter, cheese, wool, and such goods. We are led, however, by a passage in a curious Latin manuscript, hereafter quoted, to believe that the building which latterly existed was only erected a short time before the year 1650. It was removed, August 1822, to make way for the procession of George IV. to the Castle, but till this day some of the chief dealers in the above articles are settled near the spot. The Old Guard. — This was a long low building, which, we have every reason to suppose, had been erected in the reign of Charles II. and which served as a guard-house to the military police that so long protected the streets of Edinburgh. It stood upon the south side of the High Street, a little below the Cross, and had a dungeon or black-hole at the west end, which, time out of mind, had been the terror of boyish depredators, as well as of all nocturnal offenders against the public peace. With strange perversity of taste, this mean hulk was permitted to encumber the street for more than thirty years after the comparatively innocent and certainly far more elegant Cross, had been demolished. It was only removed in the year 1788.

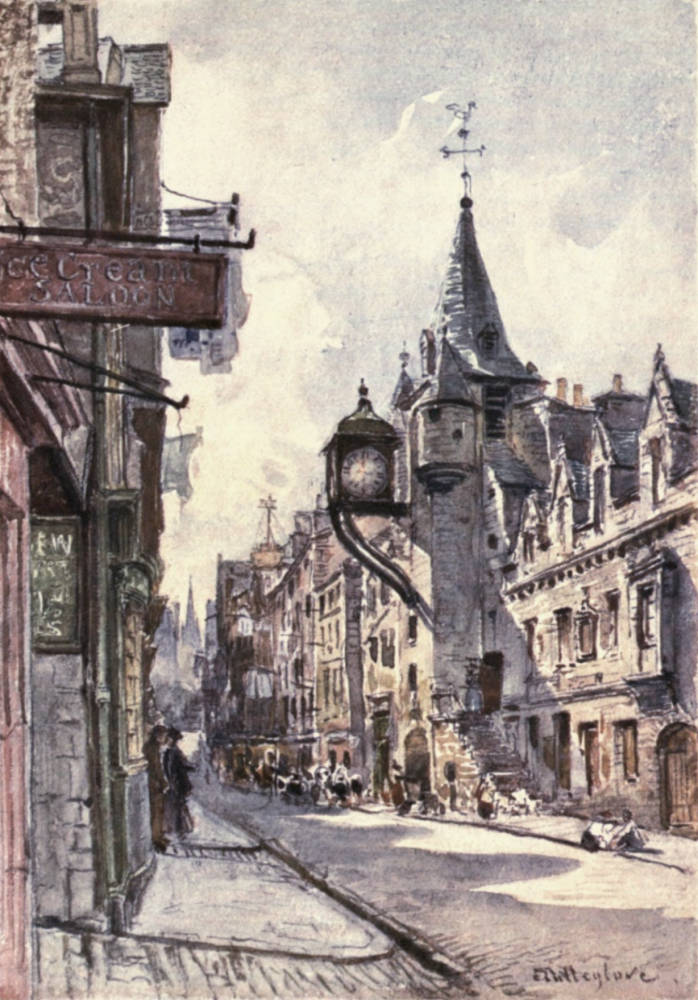

The Canongate Tolbooth, Looking West by John Fulleylove, RI. (1907). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The Luckenbooths, which were the chief encumbrance to the street, consisted of a series of tenements rising to nearly the height of the adjacent houses, built within a few yards of the church of St. Giles, and headed at their western extremity by the Old Tolbooth of Edinburgh. Betwixt the south side of these houses and the church, there was a lane for foot passengers, lined with small shops or booths, nestling within the projections of the sacred edifice, and receiving the name of the hrames. It appears that the town-council first allowed the erection of these places of retail traffic contiguous to the church, in the year 1555, but the Luckenbooths had been used in the character of warehouses and shops for the gale of cloths and goods of that nature, in all likelihood from the period of James III, when the sites of the different markets were regulated. The tenements are supposed by some to have taken their name of Luckenbooths from Laken, a word for cloth; but it is much more probable that the designation is from the Scotch word Lucken, signifying shut or close, which might be applied as distinguishing the first buildings erected here from the open piazzas or booths which prevailed along the ordinary streets. At the east end of the passage of the krames, and at the north-east comer of the church, was a small flight of steps, styled Our Lady's steps, from a statue of the Virgin Mary being fixed in a niche in the wall above. At the Reformation, " Our Lady" was unceremoniously handed down from the exalted station she had long occupied; yet such was the force of custom among the good burgesses, that, till a very late period, the " steps" were considered the most sacred place on which bargains could be concluded. The opening of a number of new shops in modern parts of the city deranged the traffic of the Luckenbooths, and a resolution being formed to remove them from the street, the central houses in the row were demolished in the year 1801; but the tenement on the east, facing down the street, and that on the west, or the Tolbooth, continued standing till 181617-18. The house on the east was long occupied in its lower flats as the book-shop of Provost Creech, a gentleman, who graced his profession by literary acquirements of an order which constituted him not only the publisher but the companion of the luminaries of the Scottish capital in the decline of the last century. Till our own times, an evidence remains of the Luckenbooths having been a considerable mart of cloths, as several of the principal dealers in these goods are yet settled in the vicinity.

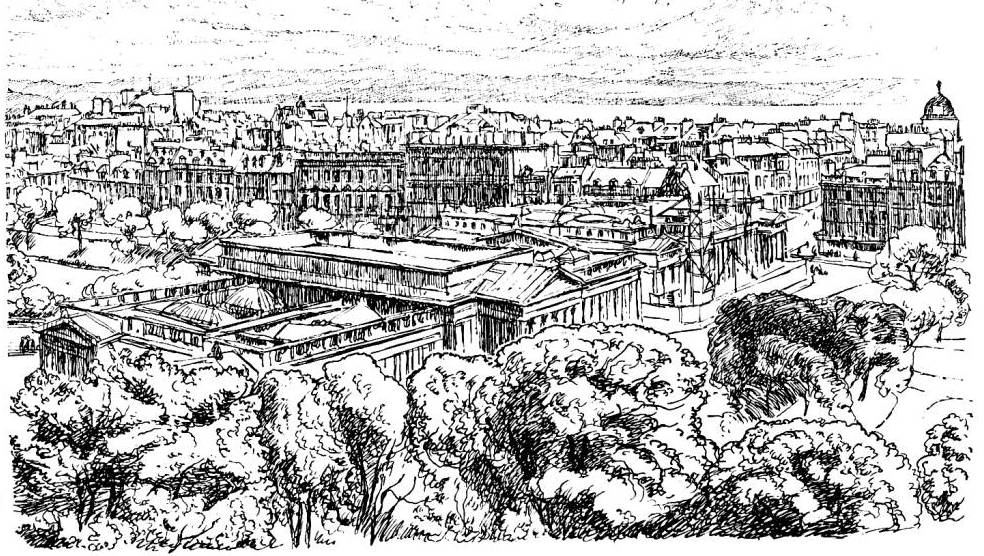

The High School and Burns’s Monument from Jeffrey Street by John Fulleylove, RI. (1907). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

The Old Tolbooth. — This was an edifice of considerable but unknown antiquity, though very probably erected before the reign of James III., when we find that parliaments were occasionally fenced in the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, and the magistrates let twelve shops in its ground flat at a certain rent each. Tolbooth signifies literally the shop where taxes are collected; but as it seems to have been applied generally to the species of mansion now called a town house, (in France a hotel de ville,) we are to suppose that this served originally the same purpose which is now served by the Council Chamber in the Royal Exchange. Perhaps, the purposes of the building were of a mingled nature; it might serve in part as a jail, according to a fashion not yet uncommon in Scotland, and also as a place for depositing the goods of the merchants when any danger was apprehended. The character of a townhouse appears to have long ago departed from the building, for in the reign of James VI. we find that the parliament and law-courts met in the south-west department of St. Giles's Church, which then went by the name of the Tolbooth, (since the Tolbooth Church,) the ancient building being now styled the Old Tolbooth, to indicate disuse. Whether it now became a jail exclusively, we are unable to say; but certainly it had been used from time immemorial as the ordinary jail of the city and county. It was a tall narrow edifice, composed of two parts; one of which, towards the east, was a square tower of polished stone, with a spiral stair at the corner, resembling in every respect an ordinary Border peel-house; while the western department was of a parallelogramatic form, composed of ruble-work, and apparently an after-thought, or addition to the jest. The east end, as it was called, contained a common hall for the recreation of the debtors; but the upper apartments were exclusively devoted to the incarceration of criminals, the uppermost containing a strong iron box, or cage, which had been fabricated for the preservation of some notorious jail-breaker of a past age. The west end contained the apartments of the debtors. In former times the superintendent of this gloomy mansion was styled "The Goodman of the Tolbooth;" but, in later times, as in the case of the present jail, he was designated by the term "Captain." A cant name for the edifice was "the Heart of Mid-Lothian," under which title it is commemorated by the pen of the most fascinating of all modern writers. From the year 17S5 downward, a platform at the west end of the building had been used as the ordinary place of execution; the spot since assumed is at the head of Liberton's Wynd, in the immediate neighbourhood. The Tolbooth also exhibited, in early times, the heads of eminent traitors and criminals, which were stuck upon a spike rising from one of its lofty pinnacles. Among the most memorable of these persons, we recollect the names of the conspirator Earl of Gowrie and his grand* nephew the Marquis of Montrose.Parliament Square

Coeval with the demolition of the Luckenbooths, several improvements were made on the south side of the edifice of St. Giles, which lined the north side of the Parliament Close. The ground covered by this small square and the public and private edifices on its south side, towards the Cowgate, previous to the seventeenth century, was used as the church-yard of St. Giles, and might be considered the metropolitan cemetery of Scotland; as, together with the internal space of k the church, it contained the ashes of many noble and remarkable personages. John Knox was here" interred. The Regent Murray was buried within one of the adjacent aisles of the church, and within the same structure was interred the Marquis of Montrose. After the period of the Reformation, when Queen Mary conferred the large cemetery of the Grey Friars on the town, the church-yard of St. Giles ceased to be much used as a burying-ground; and that extensive and more appropriate place of sepulture succeeded to this in being made the Westminster Abbey of Scotland.

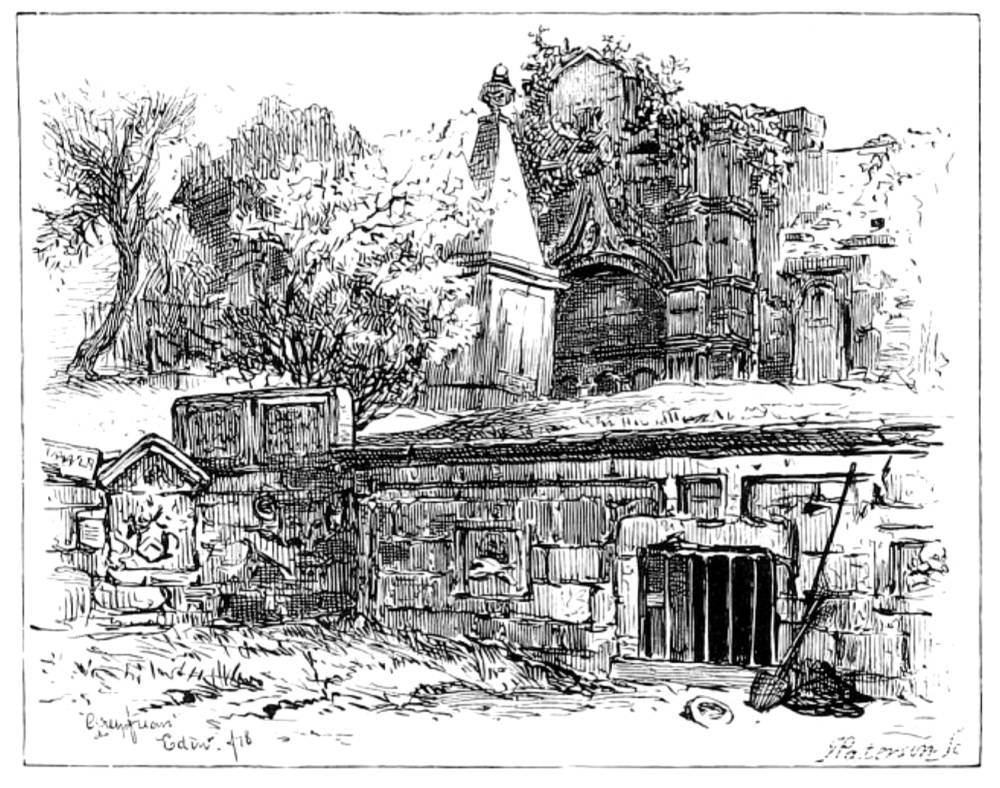

Two drawimgs of Tombs in Grey Friars from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The church-yard of St. Giles appears to have entirely lost its sacred character about the period of King James' departure for England, and in 1628 the church was first degraded by numerous booths being stuck up on this side of it, similar to the krames on the other j though, out of reverence to the sacred edifice, the town-council decreed, that no tradesmen should be admitted to these shops, except booksellers, watchmakers, jewellers, and goldsmiths, which were considered the most respectable trades then in existence. In 1632, the great hall of the parliament house was founded upon the site of the houses formerly occupied by the ministers of St. Giles, and this building, when finished in 1639, closed up the west side of the area. About fifty years afterwards some large tenements of not less than fifteen storeys in height were erected on the south side, but these being burnt down, as formerly noticed, in 1700, houses of about eleven stories were erected in their stead. In the course of time the Parliament Close or Square was altogether enclosed with handsome houses, and the area being neatly paved, there was an air of gran» deur and comfort about it, which struck most visitants.

The Parliament Square continued in this respectable condition till the epoch of the demolition of the Luckenbooths, when the small shops being torn from the side of the church, a ruinous appearance was communicated to the Close, from which it never recovered; and in the course of the great fires of 1824, all but the court-houses were laid totally waste. Till this last and greatest calamity, the Parliament Close was the chief Lion of the metropolis, as, independent of its antique imposing character, and the glittering shops of the jewellers around it, it contained an equestrian statue of Charles II. (erected by the magistrates in 1685,) which was the admiration of all country people visiting the capita£ On the left hand, in entering the area of the square, opposite the south-eastern corner of the church, was the celebrated John's Coffee-house, an establishment which had existed at least since the period of the Revolution, and which was long used as a place for meetings of creditors, feeing or treating council, the payment of bills, and other business. Defoe, in his History of the Union, informs us that the opponents of that great measure used to meet here, in order to speculate upon the proceedings of Parliament, over inflammatory potations of brandy.

Such have been the various extensions and alterations of the metropolis since the year 1752. Instead of one, Edinburgh is now composed of six or seven towns, each more or less devoted to the residence of particular classes of inhabitants, and distinguished by certain peculiarities of architectural decoration. Including parcels of ground not yet feued or laid out in garden plots and pleasure-grounds, the breadth of Edinburgh each way is about two miles and a quarter, and if Leith be included there will be had a continuous range of houses for fully four miles. The number of streets, places, squares, alleys, or particular buildings having distinct names in Edinburgh, Leith, and suburbs, amounted, in 1830, to 950.

New Town and Forth. Hanslip Fletcher. 1910.

Besides these causes which we have specified as leading to the extension of Edinburgh, there might be given others which have operated in later times to produce the rapid rise of new streets in all quarters of the environs. The proximity of inexhaustible stores of free stone, whinstone, and lime, and the ease with which foreign timber could be introduced from the north of Europe, have undoubtedly been the immediate means of bringing Edinburgh to that extent and pitch of magnificence which excite the surprise of most strangers; it is equally certain that these means might have lain long dormant but for the powerful influence of a paper currency. In this respect Edinburgh has possessed qualifications enjoyed by no other town in Europe. The profuse dissemination of Bank notes on those secure principles, which, by making them merely the representatives of property, whose bulk incapacitates it from being transferred like a coin, have made the Banking system of Scotland the admiration of all who reflect on its properties, — has been the grand cause of the extraordinary extension of the city. However, as in all projects there is a point beyond which it is unsafe to proceed, the mania for building in Edinburgh received a check from the financial panic of 1825, and at present no more houses are in the progress of erection than what is dictated by a reasonable demand.

In whatsoever style of architecture the houses of the modern parts of the town have been reared, they do not rise beyond an average height of three stories, exclusive of a sunk oi area flat. The latter peculiarity of construction, though common in the modern streets of London, Bath, &c. may be reckoned a very striking distinction of the Edinburgh houses. The whole of the new streets in Edinburgh, with hardly an exception, have areas and rails in front, while the main doors are approached by steps and a species of bridge. This mode of construction renders the houses free from damp, but it is working a serious evil in the comfort of the town. It has happened that, little by little, shops have been opened in the New Town houses, and as they advance, the higher classes of people remove to a greater distance. In breaking up the houses into shops a curious process is resorted to. The two lower storeys of the houses are cut out and rebuilt with larger windows, and different internal dimensions, leaving a sunk or area flat of small shops, and a higher flat containing one or more of a superior order, by which means the finest shops must all be entered by an outside hanging stair. Such an arrangement jrenders the shops very ill adapted for business, and this more especially as the shops in the areas are, for the most part, let as taverns, or for more mean occupations; frequently, indeed, they stand shut up, defacing the beauty of the streets, injuring the shops above, and making no return to the landlord. In only two or three instances have proprietors sacrificed the sunk flats, and made the respectable shops level with the thoroughfares. All the chief modern streets have small enclosed spaces behind, as private grounds, and betwixt these and the other streets there are lanes with stables.

The general annual rent of shops in Edinburgh, in first-rate situations, at present varies from £60 to £200, though, in a few instances, considerably above this. In second-rate places, they are rented from £30 to £40. The rents of flats of houses in and about the New Town, varies from £30 to £60. Self-contained houses are let at from £30 to £200. To these sums a fifth part more may be added for city and police taxes. It is seldom that houses or shops in Edinburgh are let on lease for more than five years. The actual annual rental of the town, within the bounds of Police, is at present about £500,000.

Bibliography

Chambers, Robert. The Gazetterr of Scotland. Edinburgh: Blackie and Son, 1838. Internet Archive online version digitized with funding from National Library of Scotland. Web. 30 September 2018.

Last modified 23 February 2019