n late May of 1857, likely May 25, the first group exhibition devoted to the work of the Pre-Raphaelites and some of their close associates and followers opened in two rooms on the first-floor of a private house at No. 4 Russell Place, Fitzroy Square, London (Fredeman, Rossetti Correspondence, 159). The exhibition continued for roughly a month. In that year Pre-Raphaelite paintings that had been submitted to the Royal Academy summer exhibition were either rejected or badly hung and this provided an impetus for a self-supporting exhibition not dependent upon that institution. The exhibition must have been organized and mounted very quickly since the Royal Academy exhibition itself had only opened on May 4. As Ford Madox Hueffer stated: “The exhibition, from its private nature, was not - nor indeed was it intended to be - a rival to that of the Royal Academy. Nevertheless, the idea of some exhibition directly and ostensibly in opposition to that of the Academy was vigorously discussed at nearly every meeting of the Pre-Raphaelites” (Ford Madox Brown, 144).

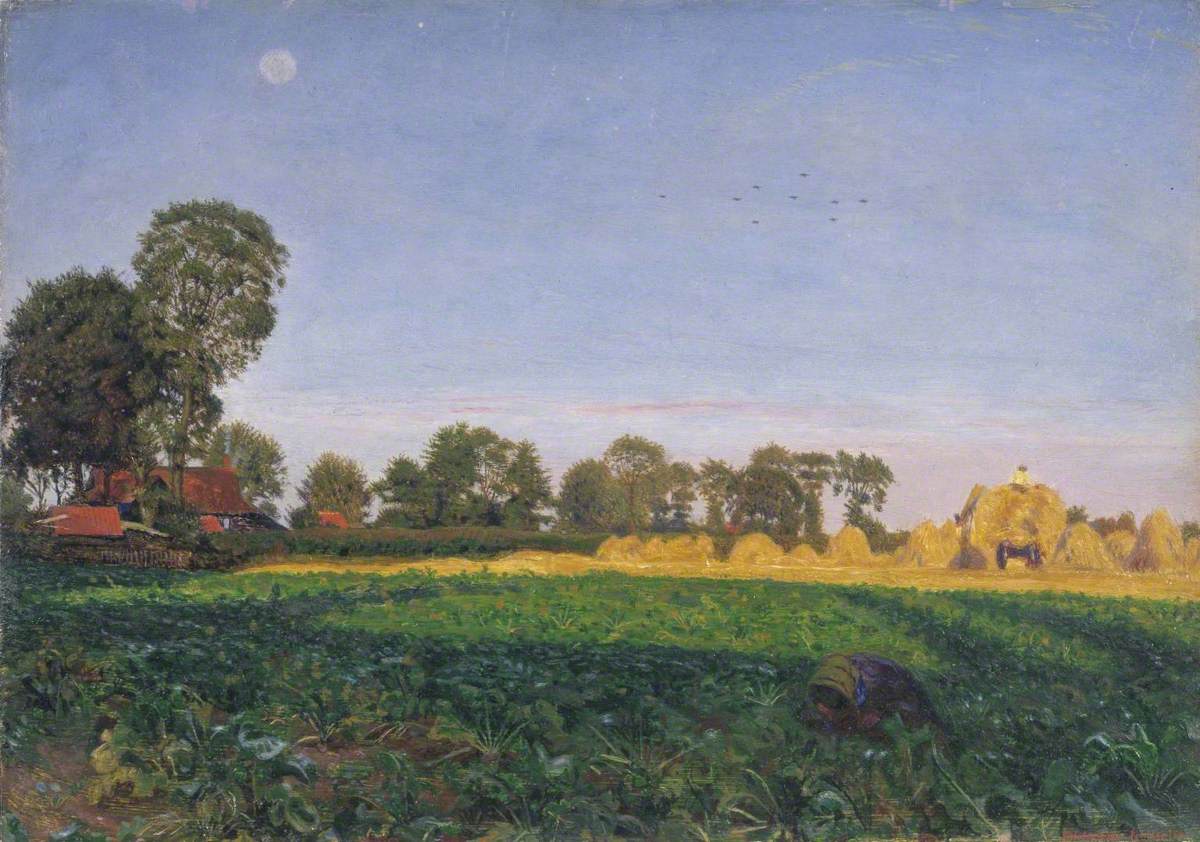

Left: The Last of England by Ford Madox Brown, 1855. Oil on panel, 32 ½ x 29 ½ inches (82.5 x 75 cm). Collection of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, accession no. 1891P24. Right: Carrying Corn by Ford Madox Brown, 1854-1855. Oil on mahogany panel, 7 ¾ x 10 5/8 inches (19.7 x 27 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. N04735. Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Russell Place exhibition, largely organized by Ford Madox Brown, was a semi-private affair. Admission was by invitation only, thus avoiding contravening the ban imposed by the Royal Academy that would disallow the exhibition of works previously shown in public. Brown paid the £42 expense of mounting the exhibition initially out of his own pocket, but each of the twenty-two artists who exhibited works was expected to contribute to the cost. Although some pictures on view were on loan from private collectors, many of the works were for sale. It was hoped that the sale of works to visitors would more than recoup the money required to put on the exhibition since no admission fees were to be charged.

Left: Dante’s Dream at the Time of the Death of Beatrice by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1856. Watercolour on paper, 19 ¼ x 26 ⅛ inches (48.7 x 66.2 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. N05229. Right: The Blue Closet by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1857. Watercolour on paper, 14 x 10 ¼ inches (35.4 x 26.0 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. N03057.

The artists exhibiting works included, not unexpectedly, Ford Madox Brown, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Arthur Hughes, Charles Allston Collins, William Bell Scott, Robert Braithwaite Martineau, Michael Frederick Halliday, John William Inchbold, Thomas Seddon, George Price Boyce, and John Brett. Elizabeth Siddal was the only female artist who exhibited although others like Barbara Leigh Smith, Lady Waterford, and Eleanor Vere Boyle could have been considered. In 1854 all three, who were part of the wider Pre-Raphaelite circle, had been invited to join a Pre-Raphaelite sketching club called The Folio. Madox Brown’s old friend Lowes Cato Dickinson was included, but not his other long-term colleagues William Cave Thomas, Mark Anthony, and Charles Lucy.

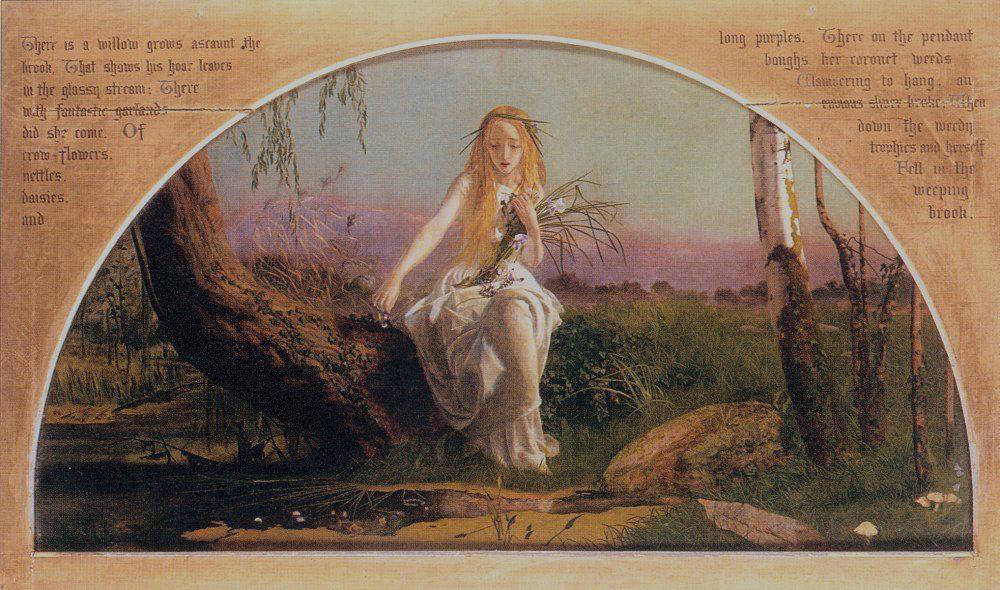

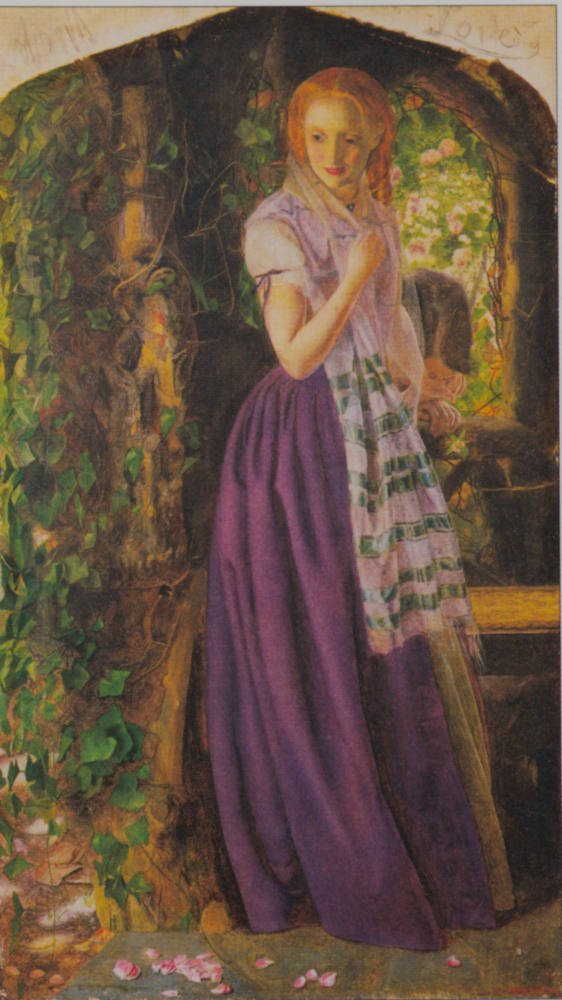

Left: Ophelia (reduced version) by Arthur Hughes, 1852. Oil on panel, 20 x 36 inches (51 x 91.5 cm). Collection of Lord Lloyd-Webber. Right: April Love (reduced version) by Arthur Hughes, c.1855-1856. Oil on panel 18 x 10¼ inches (45.5 x 26.5 cm). Collection of Lord Lloyd-Webber.

The Liverpool artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Movement were well represented, including William Lindsay Windus, William Davis, James Campbell, and W. J. J. C. Bond.

Left: The Interview Between Middlemass and his Parents by William Lindsay Windus, 1853. Oil on panel, 18 x 13 ⅞inches (45.7 x 35.2 cm). Collection of Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, accession no. WAG1592. Right: Wallasey Mill, Cheshire by William Davis, c.1856. Oil on canvas, 16 ½ x 26 inches (42.0 x 66.0 cm). Private collection.

Despite the success of William Shakespeare Burton’s A Wounded Cavalier and Henry Wallis’ Chatterton, both pictures having been exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856, neither artist was apparently invited to exhibit or else had nothing suitable to show. Wallis, for instance, had lent Chatterton to the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition that had opened on May 4. Both painters would later become members of the Hogarth Club, however. D. G. Rossetti’s young protégés, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, were not included because the exhibition was held too early in their artistic training.

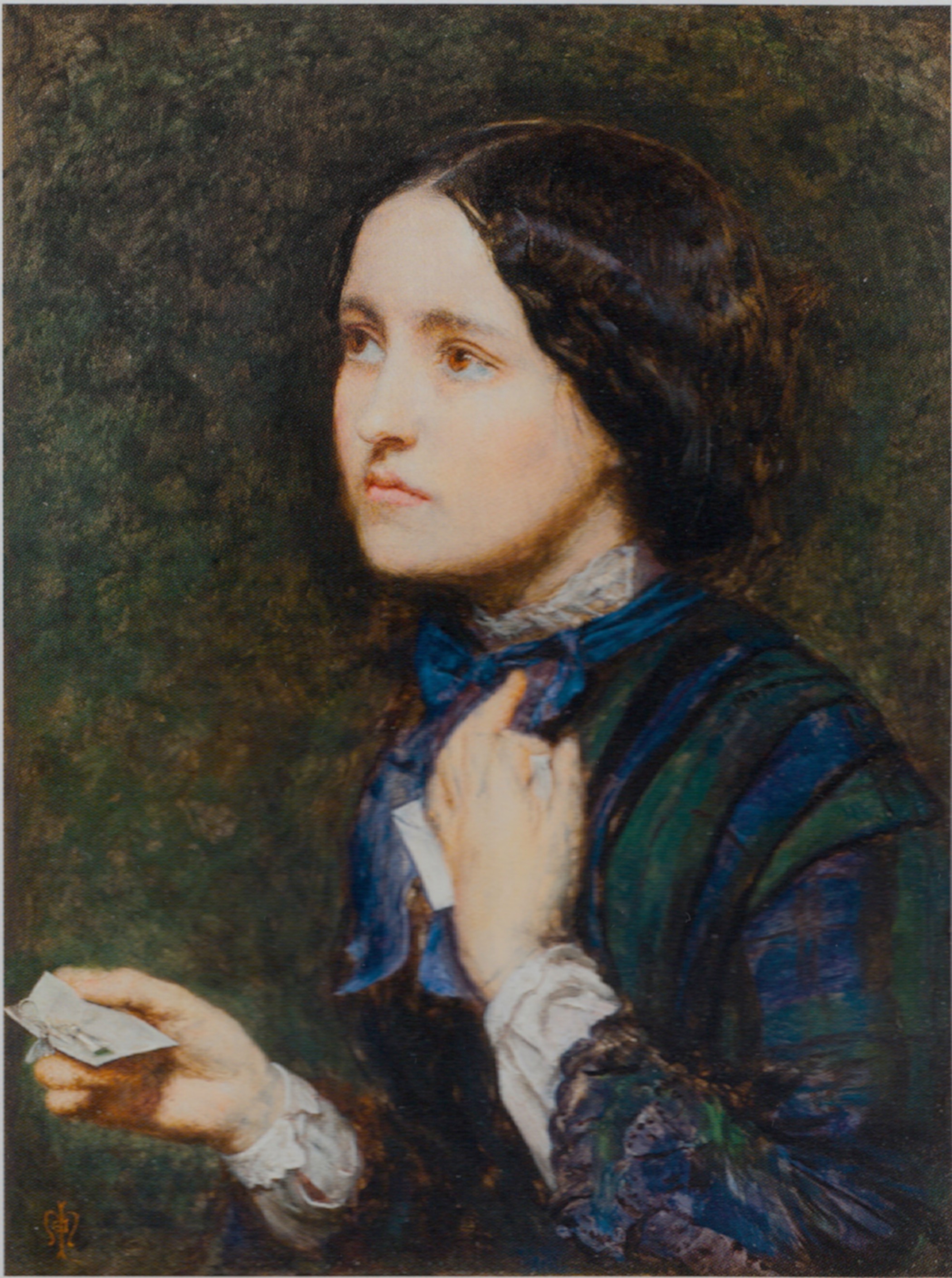

Left: The Foxglove by John Everett Millais, 1853. Oil on board, 14 ½ x 13 ¾ inches (37.3 x 35.1 cm). Collection of Wightwick Manor, Warwickshire, the Mander Collection, National Trust. Middle: The Wedding Cards by John Everett Millais, 1854. Oil on canvas, 8 ¾ x 6 ½ inches (22.2 x 16.5 cm). Private collection. Right: Clerk Saunders by Elizabeth Siddal, 1857. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 11 ¼ x 7 ⅛inches (28.4 x 18.1 cm). Collection of Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Image courtesy of the Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Perhaps most surprising of all was the inclusion of Arthur James Lewis, Joseph Wolf, and John Dawson Watson, of whom only Watson could later be considered a significant Victorian artist. Early in his career Watson painted in a Pre-Raphaelite manner. In 1856 John Miller had purchased some of his figure subjects thereby attracting the attention of Ford Madox Brown who had a certain admiration for Watson. Wolf was best known as a painter of birds. None of these three artists were intimates of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, however, and none later went on to become members of the Hogarth Club when it was founded in 1858. Lewis was a wealthy silk merchant and amateur artist perhaps best known for founding the Junior Etching Club. Although Lewis did apply to join the Hogarth Club, his application was blackballed. (Rossetti Correspondence, letter 58.25n, 235). The inclusion of so many Liverpool painters was probably the result of Brown’s great friendship with the painter William Davis, and also with the Liverpool collector John Miller. Miller was an enthusiastic supporter of the exhibition and anxious to see that it had a major impact on the London art world. He not only lent works from his own collection, but also arranged loans of other pictures. Prior to the opening Miller wrote to Brown: “One thing I advise you, and that is to hang nothing whatever but what is first rate, and passed as such by your select committee. You may thus make your little exhibition extremely attractive – it will be the reverse of the Royal Academy both in quantity and quality” (Hueffer, 144).

Left: Mount Zion by Thomas Seddon, 1854. Oil on canvas, 17 ¾ x 13 ¼ inches (45.1 x 33.7 cm). Private collection. Right: >The Haunted Manor by William Holman Hunt, 1849. Oil on board, 9 ¼ x 13 ¼ inches (23.3 x 33.7 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. T00932.

Despite being a semi-private exhibition it was well reviewed in the press. The most complete and sympathetic notice was provided by that great friend of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the poet Coventry Patmore, in Saturday Review:

There were in all seventy-two pictures and drawings, and with a very few exceptions, they were all worth looking at. In this and in other respects the display was a singular and instructive one; but it was especially interesting as showing what are the real views and aims of the people calling themselves pre-Raphaelites. There could scarcely be a greater diversity of styles and natural capacities than in the score or so of artists whose works were here collected together; but there was one property common to all, or very nearly all, the pieces displayed. Notwithstanding the abundant immaturity to be detected in some of them, we confess that we do not remember to have seen any equally numerous collection of modern pictures equally distinguished by the property we mean–namely, that resulting from the artist’s simple and sincere endeavour to render his genuine and independent impressions of nature. From Seddon and John Brett, whose eyes are simple photographic lenses, to Gabriel Rossetti and Holman Hunt, who see things in ‘the light that never was on sea or land,’ but which is, for all that, a true and genuine light, everything, as a rule, and as far as it goes, is modest, veracious, and effective. The one or two exceptions to the rule remarkably prove its predominance…There were several other pieces in this exhibition entitled to praise, and not a few which might call for blame, but that the private nature of the display may be allowed, to some extent, to disarm criticism by considerations of courtesy. [11-12]

Another review was in The Athenaeum, likely by Walter Thornbury who was their art critic at that time.

A Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition, perhaps the germ of more important self-assertions and reprisals, has lately been held privately in Russell Place, Fitzroy Square. If the Academy will not do justice, they will not be shown justice. Pre-Raphaelitism has taught us all to be exact and thorough, that everything is still unpainted, and that there is no finality in Art. Its errors, eccentricities, and wilful aberrations are fast modifying and softening. Its large hands and feet, ugly, hard, mean faces, gaudy colours, and streaky stipplings have subsided into common sense, good taste, and discretion. [886].

Patmore stated in his review that there were seventy-two pictures and drawings included in the exhibition, but this was not strictly accurate. Knowledge of which artists were included in the show, and what was exhibited, is largely thanks to William Michael Rossetti. Some of this information was included in his book Ruskin: Rossetti: Pre-Raphaelitism, published in 1899 (171-72). A complete account, however, can be found in his hand-written list. A catalogue of the exhibition that appears to have been based on W. M. Rossetti’s notes was printed and was available at the viewing. A copy of this original printed catalogue is in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Department of Manuscripts and Books. In Rossetti’s notes, and in the printed catalogue, four of the entries are indicated by a row of asterisks. This suggests that either W. M. Rossetti did not know the title of a work, which is highly unlikely, or that no work was shown. The asterisks could possibly represent works the artist reserved places for, but which were unidentified at the time of the catalogue going to press. No works are discussed in the reviews, however, that are not listed in the catalogue, so this makes this possibility less likely. Perhaps works initially promised for the exhibition failed to materialize, either because they were not finished in time, or because the owner in the end refused to lend. D. G. Rossetti has asterisks in catalogue no. 56. He is known to have initially planned to exhibit The Tune of the Seven Towers, but didn’t finish it in time. Another possibility for the asterisks is that the hanging committee rejected certain pictures, taking John Miller’s advice to “hang nothing whatever but what is first rate.” G. P. Boyce recorded in his diary for May 26, 1857: “Letter from Wells saying he and Rossetti had been to my studio and walked off with that sunset sketch, and the crypt of St. Niccolo at Giornico, to exhibit with a collection of Pre-Raphaelite painters’ work at 4 Russell Place, Fitzroy Square” (17). While Boyce’s sunset sketch in North Wales was included in the exhibition, the second work was not, unless the subject was somehow misinterpreted as being set in Venice rather than Giornico. This is unlikely, however, because Boyce records in his diary that he visited the exhibition on June 27 and makes no mention of this. If W. M. Rossetti’s notes formed the basis for the printed catalogue, however, why were the catalogue numbers delineated by asterisks simply not omitted and the catalogue numbers rearranged if the asterisks represented pictures eventually not included in the exhibition? Perhaps the printers already had a rough draft that they had set up in print and it would have taken too much time and trouble to reset the print to take into account any last minute changes that occurred on hanging day. It obviously would have been much easier to simply remove the title of a work and replace it with asterisks. Another problem with knowing exactly how many works were shown is that catalogue no. 66 by Lizzie Siddal contained multiple sketches for Tennyson and Browning. Catalogue nos. 43 and 61 comprised photographic reproductions of designs for wood engravings for the Moxon Tennyson by Holman Hunt and Rossetti. If all their Moxon designs were included this would have comprised seven for Hunt and five for Rossetti.

Although it appears that annual exhibitions of this type was initially planned, the formation of the Hogarth Club in 1858 provided an organizing committee and an exhibition space that made this unnecessary. The first such exhibition at the Hogarth Club was not held until 1859. Many of the artists who had exhibited at the Russell Place exhibition later became members of the Hogarth Club, including G. P. Boyce, J. Brett, F. M. Brown, J. Campbell, W. Davis, M. F. Halliday, A. Hughes, W. Holman Hunt, J. W. Inchbold, R. B. Martineau, D. G. Rossetti, W. B. Scott, and W. L. Windus. Although the Hogarth Club included many of the young avant-garde painters of the day, including Frederic Leighton, Deborah Cherry states that it “was a Pre-Raphaelite venture and was considered as such by the contemporary press” (243).

Links to Related Material

- Pictures on View at the First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition, 4 Russell Place, Fitzroy Square

- The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherthood

- The Hogarth Club

Bibliography

Boyce, George Price. The Diaries of George Price Boyce. Ed. Virginia Surtees. Norwich, Norfolk: Real World, 1980.

Cherry, Deborah. “The Hogarth Club: 1858-1861.” The Burlington Magazine, 122 (April 1980): 236-44.

Lanigan, Dennis T. “The First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition.” Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies, 17 (Spring 2008): 9-19.

Hueffer, Ford Madox. Ford Madox Brown: A Record of His Life and Work. London: Longmans, Green, 1896.

Patmore, Coventry. “ A Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition.” Saturday Review 4 (4 July 1857): 11-12.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The Formative Years 1855-1862. Ed. William E. Fredeman. Volume 2. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002.

Rossetti, William Michael: Ruskin: Rossetti: Pre-Raphaelitism Papers 1854 to 1862. London: George Allen, 1899.

Thornbury, Walter. “Fine Art Gossip.” The Athenaeum No. 1550, (July 11, 1857): 886.

Last modified 12 November 2021