All the photographs here are reproduced by courtesy of the Guildhall Art Gallery. The first two were kindly provided by the Gallery itself, the last shows the cover of the book accompanying the present ground-floor exhibition, and the rest come, with permission, from the Gallery's own section of the BBC's "Your Paintings" website. Many thanks to Julia Dudkiewicz, Principal Curator at the time of the recent relaunch for all her help and information; also to Sonia Solicari, the Gallery's present Principal Curator, for her kind support. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and to find longer commentaries on the paintings. Click on other links too, for introductions to the artists, and other works by them.

The Guildhall Art Gallery

The Guildhall Art Gallery, next to the Guildhall on Guildhall Yard, designed by Richard Gilbert Scott (b. 1923, the Victorian architect's great-grandson), and finally opened to the public in 1999.

The Guildhall Art Gallery stands beside the Guildhall itself, right in the heart of the famous Square Mile. Its setting, over the site of the first Roman settlers' amphitheatre here, could hardly be more closely entwined with the history of the City. The collection itself goes back to the seventeenth century, starting with stiff, formal portraits of judges, and gathering momentum with the opening of a dedicated gallery on the west side of Guildhall Yard in 1886. In many ways a Victorian project, it is one that speaks of civic pride, and celebrates the life, tastes, and artistic vision of a populace that by then was already thoroughly cosmopolitan. Since the Gallery's 1999 rebuild here on the east side, a lovely building combining both classical and Gothic elements, it has earned an enviable reputation for shedding new light on a range of remarkable talent from those days. Subjects of notable exhibitions have been William Powell Frith (in 2006-07), Atkinson Grimshaw (in 2011-12), G. F. Watts (in 2008-09) and Sir John Gilbert (in 2011). But its recent reopening after a 15th Anniversary refurbishment and relaunch has performed little short of a miracle, bringing the collection — and the Victorians — to life in an entirely new way.

The Rehang

The main gallery, with its soft upper panels of lighting, spotlights and natural light from the balcony windows, rich Puginesque carpeting and Victorian-style picture display.

During the rehang, the curatorial team has dusted off some of the works languishing in store and contributed them to a series of thematic displays in its now dazzling main gallery. False walls have been extended over the remaining side columns to free up extra and uninterrupted hanging space, and the balcony, corridors, mezzanines and lower floors have all been put to full use as well. In the main gallery itself, groups of paintings suspended by brass chains are arranged picturesquely against deep period green, showing how the Victorians saw their own lives, or how they saw other ways of life encountered in their reading and travels, in ancient or more exotic settings. The categories chosen for the main gallery, facing away from the balcony, were Beauty and Faith to the right, and Work and Leisure to the left, with Love on a short corridor to the left between (appropriately enough) Work and Leisure, and Home and Imagination on either side of the main gallery balcony. Three further categories are displayed on the lower mezzanine long gallery and in the ground floor gallery: City, Outside, and London. On the ground floor there are also rooms for temporary exhibitions — currently, one celebrating the 120th anniversary of the opening of Tower Bridge.

Curatorship is now an art in its own right, and London offers so many top-class exhibtions, every one of them curated along deeply-considered lines, according to the interests of the curators, and/or the individual categories into which a given artist's work may fall. But this new display is a particularly appealing one. Here, great names like Rossetti and Leighton hang alongside others who may never have been so celebrated, and whose reputations may have faded, but who deserve a fresh assessment now, as well as offering new insights into Victorian culture.

Love

Thomas Faed's Forgiven, 1874.

One of the pictures that has never been shown before is Thomas Faed's Forgiven in the section on love. Here, a "fallen woman" returns to a poor family with a baby. Just placing it in this section encourages us to reflect upon the different types of love that it demonstrates: the passionate moment that produced the child, the girl's family feeling that identifies the parental home as a resort at the time of most need, the girl's maternal love that prevented her from abandoning the infant as so many did, and above all the love of the grandmother who forgives, as the painting's title indicates, and reaches out to the child even while her husband stomps away crossly. Romantic love has no place here, yet the painting is instinct with steadier affections, and hope. Rescuing such a painting from store is a signal achievement.

Home and Beauty

Left to right: (a) George Dunlop Leslie's Sun and Moonflowers, 1889. (b) Dante Gabriel Rossetti's La Ghirlandata, 1873. (c) Sir John Gilbert's A Girl with Fruit, 1882.

The categories do overlap. Faed's painting could perhaps have been in the Home section at the beginning of the balcony. That would, of course, have subtly changed the way we see it. The most eye-catching painting of a domestic interior in this section is very different. It is George Dunlop Leslie's Sun and Moon Flowers, in which two elegantly dressed women are seen preparing a flower arrangement. Here is a glimpse of late-Victorian aestheticism, still with some Pre-Raphaelite detailing, but most interesting for its palette of colours (shades of white, blue, yellow) and the whole geometry of its calm, airy, uncluttered space. This painting in turn could have been hung in the Beauty section, and that would have changed our focus, making us look less at the room, and more at the women themselves.... who would no doubt have suffered by comparison with Rossetti's more familiar and dramatically soulful and alluring La Ghirlandata — or with Sir John Gilbert's positively regal A Girl with Fruit. The latter is one of the most impressive paintings not to have featured in the previous hang. It is fascinating to see how much much depends on curatorial choice and contextualisation.

Work and Leisure

Two other paintings not in the previous hang: Left: Albert Goodwin's The Toiler's Return, 1889. Right: John Whitehead Walton's The First London Schoolboard, 1873.

In some categories, like Beauty, the curators must have been spoilt for choice. For others, however, they must have been more limited. Paradoxically, this has made them more inventive. One of the paintings representing Work, for instance, is Goodwin's The Toiler's Return, in which the "toiler" himself is quite invisible, his boat just a speck on the wide sea as it approaches land. Yet the fisherman's family has already spotted it, and are eagerly awaiting him near the fishing-nets. Their excitement, mixed no doubt with relief, tells all we need to know about his hard, dangerous days on the ocean. This leaves more to the imagination than, say, Ford Madox Brown's iconic Work, or even the other rather stunning paintings in this category, showing men at work quarrying stone or in the fields, and a woman mending nets. More special still is Walton's The First London Schoolboard, and not only because of the obvious milestone it documents in the history of education. As well as commemorating the board set up to implement and extend over the capital W. E. Forster's Education Act of 1870, it shows the very first brave women in the burgeoning bureaucracy, just a pair of them, at the otherwise all-male meeting.

That The First London Schoolboard was transferred to the gallery by the London Education Authority in 1990, and is on show now, fully satisfies one of the curators' remits: to bring London's Victorian past to a new generation of Londoners, particularly those younger ones who visit on school outings. For these, a little more information here would be helpful. Even as it is, however, the painting usefully widens the focus from manual labour. It is also a scene that will immediately strike a chord with older visitors, who perhaps work in the Square Mile, and are all too familiar with large meetings of this sort — though, fortunately, the gender ratio is likely to be far better balanced now.

Augustus Edwin Mulready's Remembering Joys that Have Passed Away, 1873.

By chance or, more likely, choice, the need for compulsory education is clearly shown in the Leisure section, which comes next to Work along the main wall on this side. Again, the curators have been inventive, and the main point of Augustus Edwin Mulready's Remembering Joys that Have Passed Away is the deprivation of leisure. A young girl and older boy, who have been plying their respective trades as match-seller and street-sweeper, are gazing wistfully at a poster on the wall advertising a pantomime. They are, of course, losing not simply the pleasures of childhood, but a good preparation for adult life. Again, it is interesting to play with different possibilities of categorisation: Mulready's painting could also have been placed downstairs in the Outside section, shifting the emphasis a little from the children themselves to their setting — a cold, snowy street on an evening before Christmas — perhaps, considering the sprigs of holly in the foreground, on Christmas Eve itself, a time of all others when they should have been inside, in the warmth of a loving home, and filled with anticipation of pleasures soon to come.

Faith and Imagination

Left: Frank Holl's The Lord Gave and the Lord Hath Taketh Away, Blessed Be the Name of the Lord, 1853. Right: William Holman Hunt's Eve of Saint Agnes (The Flight of Madeleine and Porphyro during the Drunkenness attending the Revelry), 1848.

The inner life, that of the soul and the mind, is well catered for here, most obviously in the sections on Faith and Imagination. There are some paintings here too that were not seen in the previous hang, and some old favourites. Frank Holl's depiction of a grieving family is one of the former, showing the eldest son, already in holy orders, assuming his dead father's place at the head of the table, standing rather stiffly with his eyes raised, while apparently leading his mother, brother and sisters in the short prayer of the title. Their faith may be unshaken, and they bow to the inevitable, but the artist shows the pity of it all with poignant force.

Imagination, which offered an escape from the often difficult realities of Victorian life, was another recourse besides faith. The sine qua non of any artist, it imbues every painting here. It was not necessary to visit the Orient for more sources of inspiration, though many did: there were plenty of sources of inspiration in myths and legends, sometimes in their recent retellings. Arthurian legends, or at least legends of knights and ladies, were favoured by the Pre-Raphaelites. Here is Holman Hunt showing Madeleine and Porphyro eloping in Keats's poem "The Eve of St Agnes." They are just daring themselves to creep past one of the "the bloated wassaillers," the porter "in uneasy sprawl" and a "wakeful bloodhound" (which luckily recognises Madeline and so fails to alert the sleepers). It is a moment of great tension, but at the other end of it lies freedom and (we can carry on the wishful thinking ourselves) a happy life together.

The diversity of life in the long nineteenth century, and the huge changes that occurred in it, ensure that the period resists neat categorisation. Reflected throughout the main gallery are various problematic issues: the "two nation" rift between rich and poor; different kinds of social problems and the ongoing battle against them; and the contrast of old ideals with new experiences and ideas. Cutting across boundaries too are the general opening of horizons, and the dreams (including that of the "house beautiful" with the rise of the middle class) that offered escape from bewildering realities. Yet the thematic displays help to station us, as onlookers, at various different positions, and allow us to experience the Victorians' world from a variety of new angles and in new lights. There is much to enjoy and reflect upon — and learn from — here.

Outside (and Back)

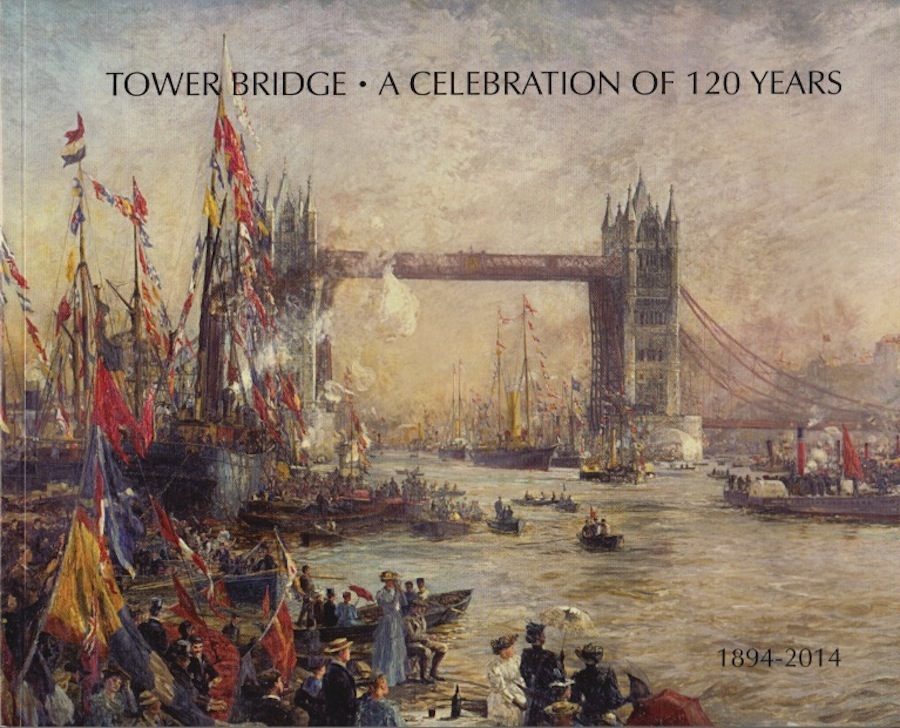

Along with her team, Julia Dudkiewicz, as Principal Curator at the time of the rehang, has done a wonderful job of bringing the Victorians back to life for us. Note that entry is free, even to the special exhibition celebrating the 120th anniversary of the opening of Tower Bridge, which fits in nicely with the themes of the lower displays (City, Outside and London, as mentioned above). Here in this discrete exhibition (free also), biographies of those involved, early proposals, contract plans and posters supplement engravings and paintings, and the gallery shop has an informative book about it, rather more than a catalogue, co-edited and with textual contributions by Dudkiewicz herself. Its front cover is graced by a detail of William Lionel Wyllie's The Opening Ceremony of Tower Bridge, 1894-95 (the whole painting is reproduced on p. 33 inside the book, details of which are given below).

As befits its role as the City's artworks' showcase, the Guildhall Art Gallery is one of London's most enjoyable galleries, with perhaps London's finest collection of Victorian work. It is not a large gallery, but many visitors will still want to come back again and again as the displays are refreshed and the exhibitions change. They may also wish to explore the remains of the Roman Amphitheatre, atmospherically presented in its subterranean hall — another of its unique attractions.

Gallery Website and Tower Bridge Book

See the gallery's own website.

Wight, David and Julia Dudkiewicz, eds. Tower Bridge: A Celebration of 120 Years, 1894-2014. City of London and Guildhall Art Gallery, 2014. £9.99. ISBN 978-1-902795-16-4. Available from the gallery.

Gallery link updated 28 April 2016