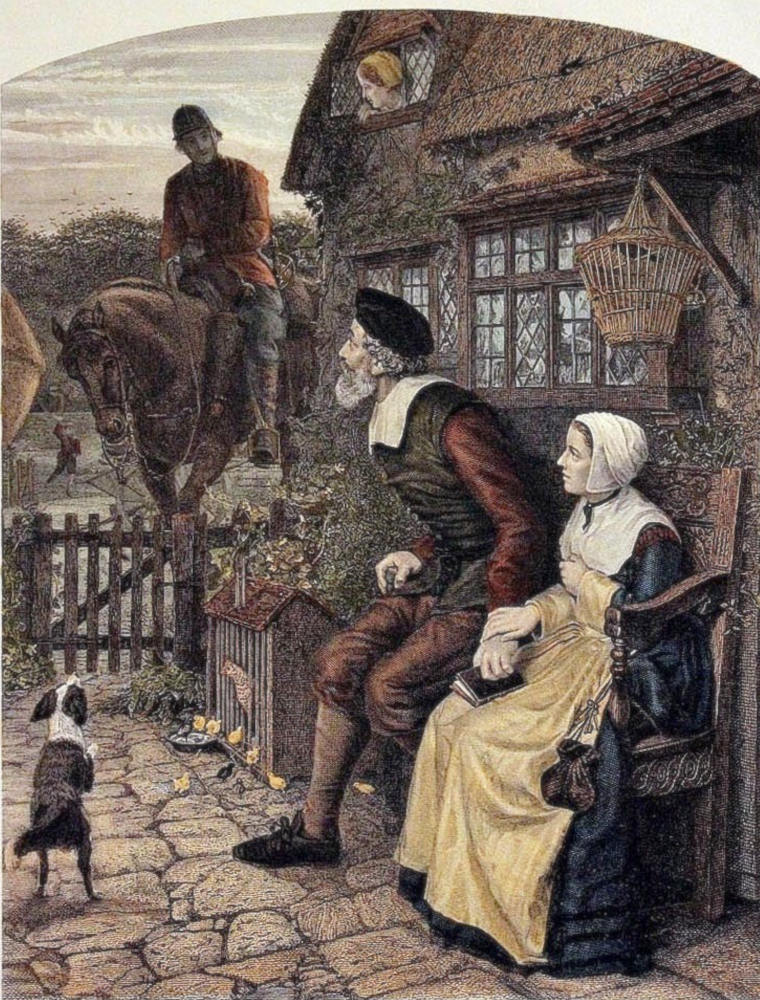

Back from Marston Moor, 1886. Steel engraving by William Ridgway with hand colouring, 93/8 x 71/8 inches (23.8 x 18 cm) – image size. Private collection.

The English Civil Wars (1642-1651) were an armed conflict between the Parliamentarians (Roundheads) and the Royalist supporters of the monarchy (Cavaliers). The Battle of Marston Moor on July 2, 1644 was one of the most critical battles of the war where the Parliamentarian and Scots Covenanter armies under Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell defeated the Royalist forces under Prince Rupert. This battle helped to decide the fate of King Charles I. The subsequent defeat of the Royalist forces at the Battle of Naseby on June 14, 1645 ended any hope of their ultimate victory.

Wallis' painting, also referred to as The Return from Marston Moor, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1859, no. 930, where it was described as "A cavalier soldier entering his father's farmyard, wounded from the fight" but the soldier was obviously fighting for the Parliamentarians. Although the painting is now lost, its composition can be largely surmised from the later engraving published in The Art Journal in 1875 on page 360.

The Painting’s Critical Reception

Critics expressed mixed reviews on the work, but most were unfavourable. The “Council of Four” in The Royal Academy Review expressed the unsympathetic opinion that it was

A sad retrogression of the painter of ‘Chatterton's Death’. Everything is ugly and exaggerated; and the whole is a perpetual conflict of every extravagance that could have been introduced. The lights in the flesh tones are so hot, that the figures appear roasted, whilst the shadows remind us of blue cholera. The wounded trooper is on a horse of purple, to match his own face, which is set between a smeary gamboge and emerald green sky; the boy running to meet the trooper seems walking on red hot plough shares, as if going through the ordeal by fire, and the hay ricks are in a state of conflagration. It is a most unveracious work, and the acceptance and suspension in a good position of such a monstrosity can only be for the purpose of enticing the shillings by an eccentricity.” [39]

The critic for Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine was also very obviously not an admirer of the Pre-Raphaelites. In his initial part of his review of the Royal Academy exhibition he strongly denounced three works now generally regarded as minor masterpieces of the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism: “We believe such works as the Return from Marston Moor, by Mr. Wallis – Too Late, by Mr. Windus – and The King’s Orchard, by Mr. Hughes – have for three long months attracted curiosity only to incite disgust or to provoke ridicule. Again we repeat we have full confidence that the verdict of the British public will be pronounced on the side of sobriety, sanity, and the modesty of nature"(127). Later in his review he maintained:

It is with deep regret that we have to record still another reputation wrecked in devotion to a cause which has this year betrayed its votaries into even more than accustomed extravagance. Mr Wallis, honoured as the painter of the Chatterton, has now dishonoured both himself and his cause by the ‘Return from Marston Moor.’ This artist, with others of his school, would seem to hold that genius is best shown in the transgression of the limits and the laws which all previous genius had hitherto observed. The story and intention of the picture are undoubtedly simple and heartfelt. The return of a worn and wounded knight to home and anxious parents; the eager attitude of the father rising to meet the son's approach; the homeish housewife mother, the model of domestic solicitude, are sufficient to show what power of expression is within this artist's reach, did he but soberly follow the simplicity of nature. The imitation of nature which was once the watchword of the school, is here seen in colour the most outrageous, and detail absolutely impossible. The blaze of a sunset sky, red, green, and saffron yellow, the knight's features gory with blood, or glowing from the heat of battle; roses and flowers of brazen face and staring eye, verily blind the sober vision, and darken and dazzle by excess of light. In infinity of detail the work is not less distracting. The father's beard is counted hair for hair; the swallow swooping down with swift flight is yet painted with all the detail of beak, eye, and plumage; pigeons are cooing on the distant dovecot; a barn-door fowl is crowing between the stirrup of the rider and the horse's leg, and thus from centre to furthest corner is every inch crowded with incident, till the picture, like a drop of Thames water seen in the oxyhydrogen microscope, is amazingly wonderful, but monstrously disagreeable. [132]

The critic for Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper was an exception in giving the picture a generally favourable review:

“Mr. H. Wallis is strong this year, though not with the strength of Chatterton. He has not given us a book-illustration or a horror. His story this time is complete in itself, Back from Marston Moor> (930), and requires no previous knowledge; but then the subject is not much – it is as simple as it can be, and it is rather a sun-set feeling than a story. The colouring is a little violent, not from any exaggeration of intensity, but from a slight want of fusing breadth and harmonious pervading atmosphere. In brief, the picture represents a young Puritan trooper slightly wounded, riding into his father’s farm-yard at sunset, after the disbanding of Cromwell’s army. There is nothing specially good about the young man’s expression, – but he looks quietly, gravely happy, - as Puritan youth should do, - and is intent on observing his old father’s and mother’s first start of recognition. The old couple – true John Anderson and his wife – are seated on the bench outside the cottage window, enjoying the serene grandeur of sunset, which turns them to the most alarming crimsons, yellows and purples. There is a fine rustic poetry and a true sense of the enjoyment and quietude of the country in this powerful picture. The old father, in his grave brown suit and plain hose, has caught sight of the brave lad, and is starting up to greet him, in spite of the old matron’s checking and more cautious hand. Already the horse’s knee is bumping against the wicket-gate, and the young brothers who have caught sight of him, are bounding over the farm-yard paling with a whoop and halloo. It is full of a fine muscular poetry is this picture, and a robust strength that is pure and healthy as can be. The moment is well chosen, because it is full of hope and surprise, and leaves so much to the imagination. We hear by anticipation the Quaker-like greetings, - the tales of Cromwell and his charge of Rupert and his sins – of Goring and his sinful devilry. We imagine the happy evenings, the white country bed well laundered, and the clean, humble room with the ballads on the wall. The pretty girl looking out of window is not a sister nor a cousin nor a sweetheart, as she ought to be, but simply a farm servant who hears the tramp of the horse and looks out with curiosity and wonder. It is pleasant to have so humanising a scene of a rough age recalled to us so strongly by Mr. Wallis. There must have been much of such quiet country happiness, even on the very evening when dying horses spurned the Northamptonshire turf at Naseby, or the day pikes grew bloody on Marston Moor or outside Worcester. The poetry, too, is not mere rustic poetry, but historico rustic poetry, and Cromwell’s distant trumpet rings in our ears even as we look at the flame bloom in the sky and the melting golds and crimsons of the pure sunset. The model for the trooper was, we are inclined to think, not well chosen, and the sword is an affected one, being quite exceptional in the twistings of its hilt. There are here and there in the picture what a certain Welshman would have called justly ‘affectations’” (8).

In the review the mention of “true John Anderson and his wife” is referring to Robert Burns’s famous poem “John Anderson my Jo’ written in 1789. Prince Rupert of the Rhine was the General of the Royalist Army and the chief military adviser to King Charles I. Oliver Cromwell was the Lieutenant General of the Parliamentarian Army. Lord George Goring was the Lieutenant General of the Horse, in charge of holding the West Country for the king and maintaining the siege of Taunton in Somerset.

Links to Related Material

- A critical examination of Back from Marston Moor

- Macaulay on Cromwell’s New Model Army

- Macaulay on Cromwell and Napoleon as Military and Political Leaders

Bibliography

“Conflict of the Schools.” Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine 86 (August 1859): 127-37.Lessens, Ronald and Dennis T. Lanigan. Henry Wallis. From Pre-Raphaelite Painter to Collector/Connoisseur. Woodbridge: ACC Art Books, 2019, cat. 39, 107-08.

The Council of Four. “A Guide to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts.” The Royal Academy Review, London: Thomas F. A. Day, 1859.

“The Royal Academy Exhibition.” Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (May 15, 1859): 8.

Last modified 17 October 2022