Many thanks to the curator of Kingston Museum, Seoyoung Kim, for all her help. Modern photographs by the author. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer (and the museum where appropriate) and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or to the Victorian Web in a print document. Click on the images to enlarge them.

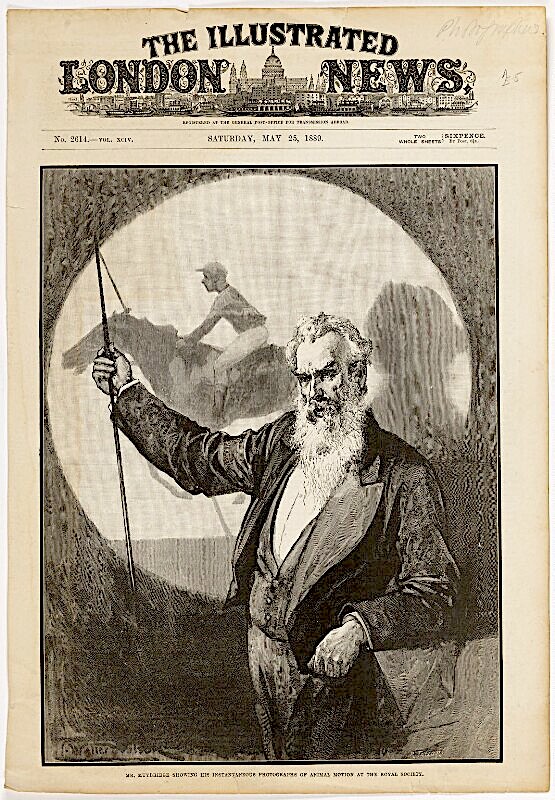

Eadweard Muybridge, by Richard Taylor, after Thomas Walter Wilson.

The Illustrated London News 25 May 1889, Courtesy

© National Portrait Gallery London (D42855).

adweard James Muybridge (1830–1904) is famous for having captured the earliest scenes of horses and other animals (including humans) in motion. He was born in the busy market town of Kingston-on-Thames, Surrey, on 9 April 1830, as the second son of John and Susannah Muggeridge, and baptised at All Saints' church a short walk away. There, he was given the more prosaic name of Edward James Muggeridge. Young Edward's father was a corn-chandler with a sideline in selling coal for barges, and his mother came from a barge-owning family at Hampton Wick, on the other side of the river. The family lived on the two floors above the corn-chandler's business premises, on what was then called West-by-Thames street, but is now part of the High Street. Little is known about Edward's early boyhood, except that he had two younger brothers as well as an elder one, and was described in a cousin's memoir as having been an "eccentric boy, rather mischievous, always doing something or saying something unusual, or inventing a new toy or a fresh trick" (qtd. in Braun 14).

Plaque above the former office of Muybridge's father.

John Muggeridge died in 1843, leaving his wife and elder son, also called John, who was still only thirteen years old, to take charge of the family business. However, his mother must have borne most of the responsibility, because John was studying to be a doctor when he died just four years later. Edward, next in line to help, was not content to stay long in the business either. He clearly had an adventurous streak, and after a few years emigrated to America in 1852. In New York he was still signing himself "E. Muggeridge" (see Braun 26), but at some point, or points, he showed his eccentricity by adopting new spellings for both his names. When he changed the way he wrote his Christian name, he may have had in mind, as Larry J. Schaaf suggests, the discovery of the Anglo-Saxon coronation stone in Kingston, on which no less than three of the kings' first names appear in that form. The stone had been put on show in the town's market place in 1850, and was later moved even closer to the family's home. It now stands just opposite the old Clattern Bridge — which may have given him the idea for writing his surname, as well his first name, differently.

Left to right: (a) The Saxon kings' Coronation Stone nearby. (b) Close-up of one of the kings' names inscribed on the base ("Eadweard"). (c) The medieval Clattern Bridge almost opposite, very close to the Muybridges' home. Its name probably comes from the noise of horses' hooves. (d) The other side of the bridge, where the span was widened in the mid-nineteenth century.

Muybridge in America

Muybridge's business experience stood him in good stead in America, where he took up bookselling. This was how he first encountered the new art form to which he would make his startlingly new contribution: "He soon prospered in the business of importing English books, and by 1855 his befriending of the New York daguerreotypist Silas T. Selleck brought him into contact with the emerging art of photography...." (Schaaf). Muybridge followed Selleck to San Francisco that same year, a canny move because the town was booming as a result of the Californian goldrush At first, he stayed in the bookselling business, but he was now selling photographs as well. He was doing well enough to encourage first one of his younger brothers, George (1833-1858), then, when George died of tuberculosis in 1858, his youngest brother, Thomas (1835-1923).

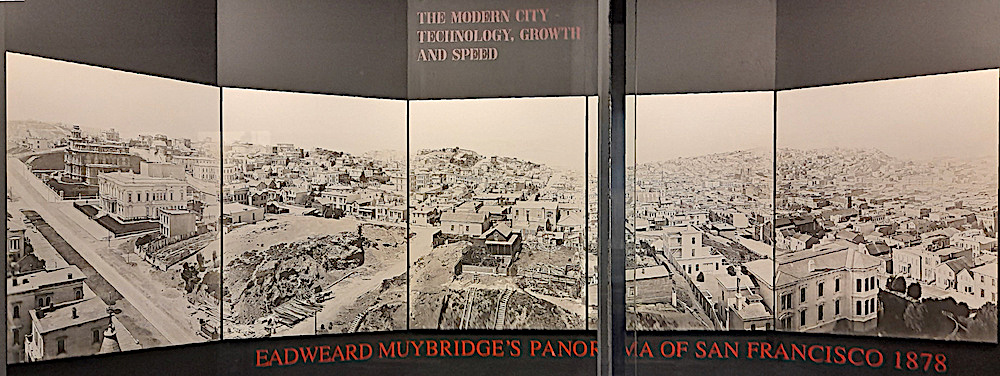

Five reproduced plates of Muybridge's original thirteen-plate panorama of San Francisco, taken in 1878, and now part of Kingston Museum's collection. The original plates, joined in concertina fashion, open into a complete circle. (Photograph taken in the museum.)

Commissioned to make photographic surveys of the country, and eventually becoming the director of such surveys, Muybridge himself continued to travel, taking his equipment with him in a "flying" studio and using the pseudonym "Helios," after the Greek sun god. He also took trips to Europe, including a prolonged visit to England to recover from a serious stage-coach accident. He had not at all lost contact with his English family, for some part of this time staying with his mother, who had moved in with her sister in St John's Wood. During these years, in the early to mid-sixties, he learned the process that would be so important to his later discoveries — wet plate photography (see "Eadweard Muybridge..." and Schaaf).

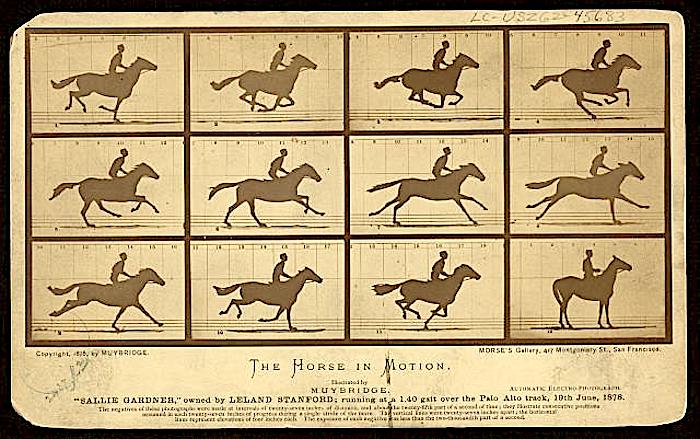

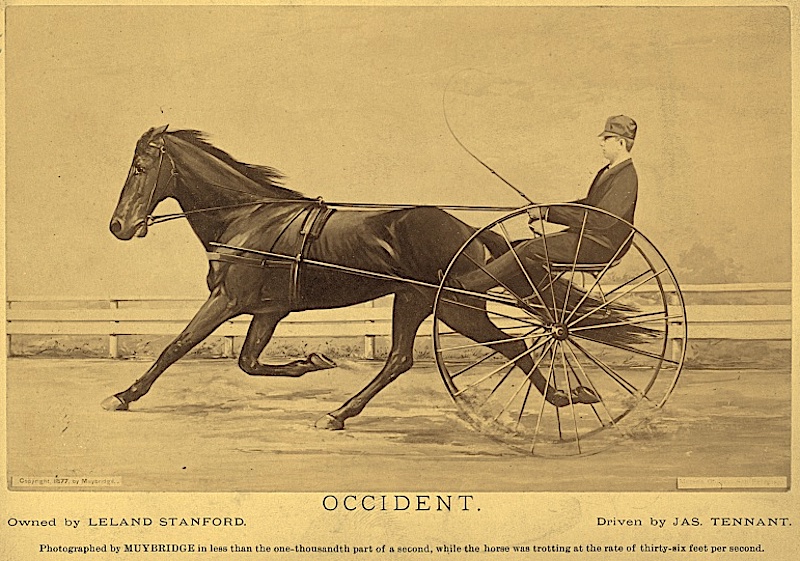

Muybridge's photographs of the horse in motion. Source: Library of Congress. Left: "'Sallie Gardner,' owned by Leland Stanford, running at a 1:40 gait over the Palo Alto track, 19 June: 2 frames showing diagram of foot movements. California Palo Alto, ca. 1878: https://www.loc.gov/item/2007678037/. Right: Muybridge's photograph of 'Occident,' owned by Leland Stanford, driven by Jas. Tennant, in Sacramento California, ca. 1877: https://www.loc.gov/item/2005694393/.

Back in California, at a race-course in Sacremento and then at a stud-farm in Palo Alto, owned by the industrialist and senator, Leland Stanford, Muybridge finally made his own (medievalised) name. At Sacramento, in May 1872, he proved through a series of camera shots that all four of a horse's hooves lost contact with the ground while the animal was trotting; and at the stud farm five years later he made the series of shots that really captured "animal locomotion" in detail. For this experiment, he adopted the idea of using strategically placed cameras from his fellow-photographer, based in England, Oscar Rejlander. The series was published in the following year (1878) as The Horse in Motion. The art world took note, and both painters and sculptors adapted their representation of animals accordingly.

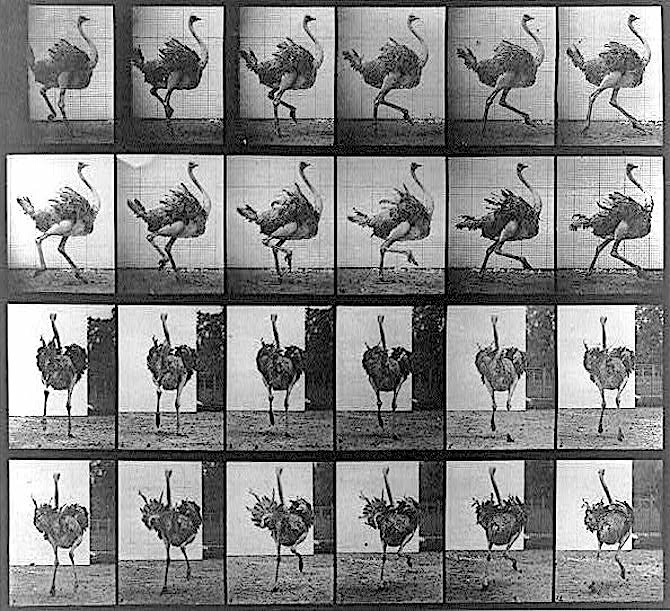

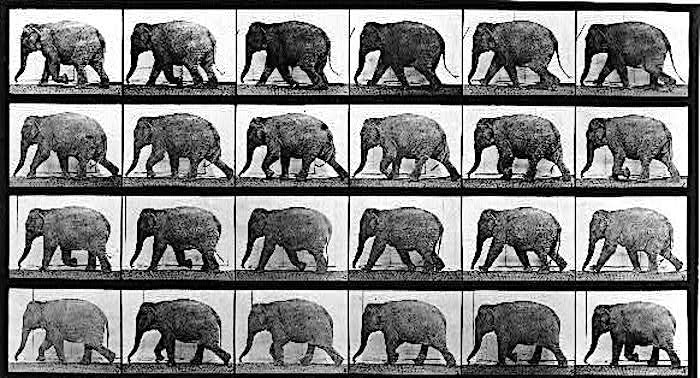

Images of animals of all kinds. Source: Library of Congress. Left: Muybridge's photographs of an elephant, ca. 1887: https://www.loc.gov/item/2003653798/. Right: An ostrich, ca. 1887: https://www.loc.gov/item/93503785/.

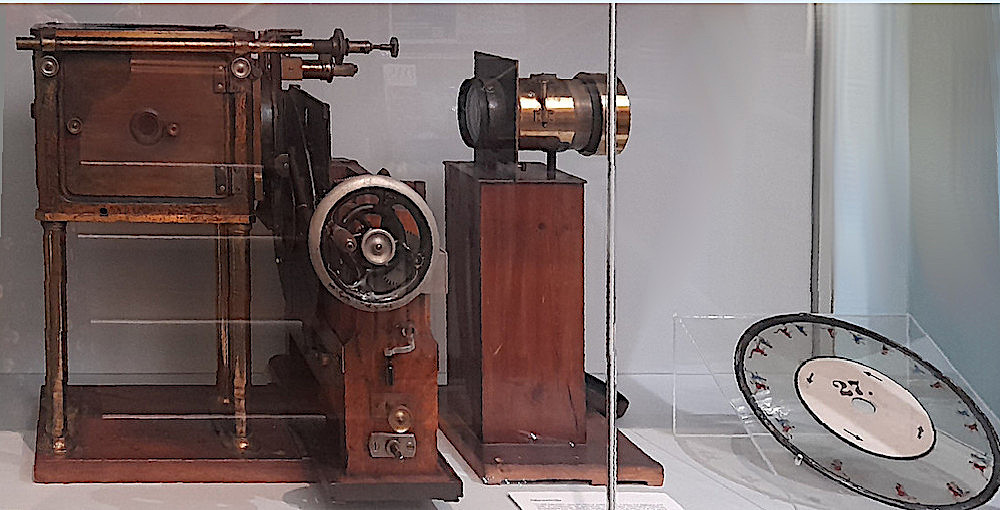

Next, in 1881, came Muybridge's invention of what he called the "zoopraxiscope," which allowed him to show his photographic sequences is such a way as to give the illusion of moving pictures. He also made use of an earlier invention, the "zoetrope," or "wheel of life." That September, he presented his work at the electrical congress in Paris, and in March of the following year (1882) at the Royal Institution in London, followed by lectures at the Royal Academy of Arts, the Savage Club, the South Kensington Museum (later the V & A), and even at Eton. This visit to England was marred by the publication of a book on which Stanford had collaborated with a friend, the physician Dr J. D. B. Stillman. The book used several of Muybridge's photographs and many lithographs of his work without either crediting him at on the title page, or including his planned introduction to it. It just had a "very casual acknowledgement in the text of Muybridge's contributions ... 'I employed Mr. Muybridge,' Stanford wrote, and that was all that was said of the overwhelmingly significant work that Muybridge had done" (Hendricks 145-46). Muybridge attempted to win redress in America, but a law suit against Stillman, and a further one against the publishers, failed to resolve this issue satisfactorily.

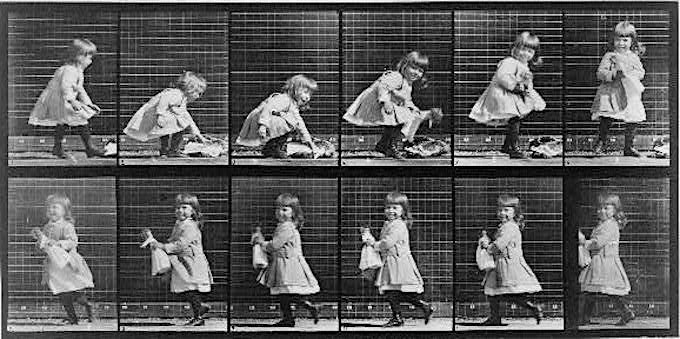

Left: Muybridge captures the movements of a little girl picking up her doll and walking along with it, ca. 1887. Source: Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/96513693/. Right: Projecting equipment used by Muybridge for his touring lectures in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. (Photograph taken in Kingston Museum.)

Nevertheless, Muybridge outrode his humiliation. Such was the academic interest in these new developments that the University of Pennsylvania asked him undertake many more such experiments in the mid-1880s: it was in Philadelphia that Muybridge published the eight folio volumes of his mammoth Animal Locomotion, an Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movement, 1872–1885, with over 2000 figures of people and animals of all kinds, in 781 photo-engravings. In March 1889 he participated in a "conversazione" held by the Royal Society. Several other associated publications followed, notably, ten years later, a downsized selection from his Animal Locomotion, which was published in London.

No invention takes place without concerted efforts. Muybridge's work had been encouraged by Dr. Étienne Jules Marey, a highly respected French physiologist who was a professor at the Collège de France, who credited Muybridge for inspiring him to use photography in his later research (see Hendricks 111). While Muybridge was the first to show motion pictures actually taken from life, Dr Marey's next step — the invention of the celluloid roll film in 1890 — would finally make cinematography possible.

Muybridge's personal life was full of other incident, including the bad stage-coach accident from which he never fully recovered, and, much more dramatically, the shooting dead of his wife's lover (whom he had just learned was the father of the child he had thought was his). This was in 1874, but the two events may not be unconnected, because of the kind of head injury sustained in the much earlier accident. Indeed, this came up in his defence at the trial in February 1875. At any rate, as Jennifer Warner puts it, "Because murder was common in 1870s California, and he was clearly the wronged party, a sympathetic jury acquitted Muybridge" (10). But, perhaps not coincidentally, this was "the last time in California that an acknowledged murderer was acquitted without an insanity plea" (Hendricks 76).

Return to Kingston on Thames

Left: Another beautifully preserved projector. Right: Muybridge's original zoöpraxiscope with one of his zoöpraxography discs. (Both photographs taken in Kingston Museum.)

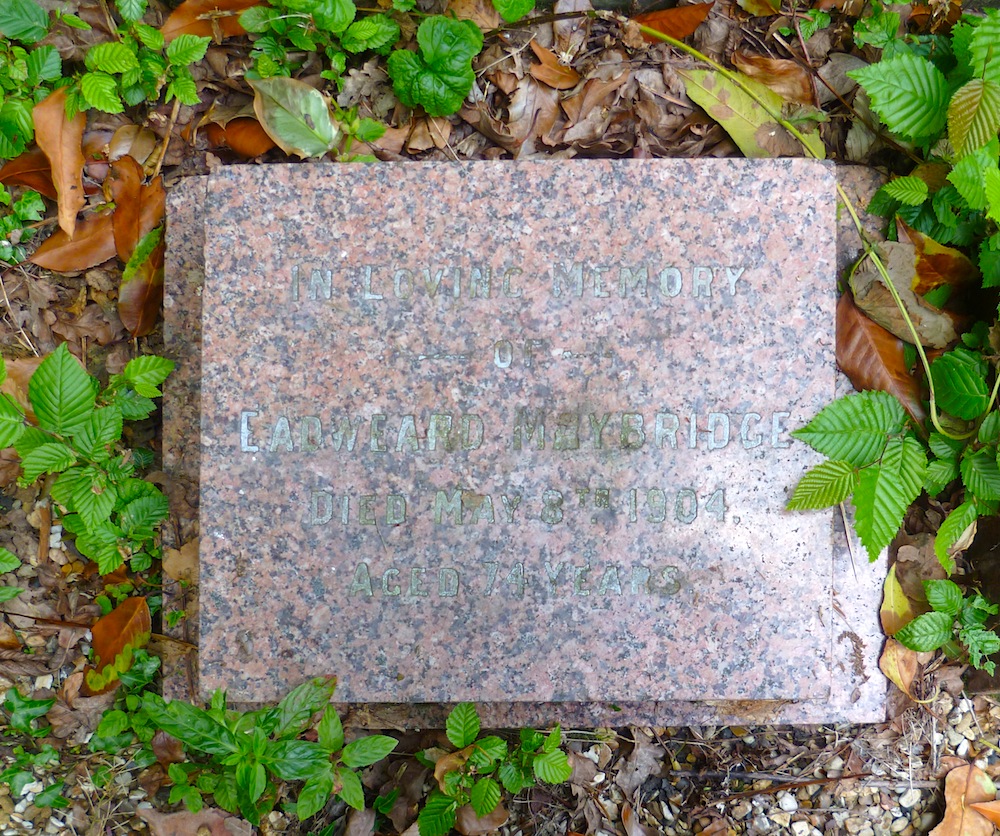

After a successful projection tour of Europe in 1891, and a disappointing showing at the Columbian World's Fair in Chicago in 1893, Muybridge returned to England in 1894, and remained there for good, apart from one last visit to America in 1896-97. He now settled in Kingston again, staying part of the time with his cousin's half-brother, George Lawrence, whom he made his executor. He must have been torn between the two countries he had lived in: something must have given rise to the story, dismissed as a myth by at least one biographer, Stephen Barber, that he died while digging a miniature but properly scaled version of the Great Lakes in the back garden (47). More prosaically, he is known to have suffered and died of "a four-months' disease of the prostate gland" (Henricks 226). His death took place on 8 May 1904. He was cremated at Woking Crematorium in St John's, Woking, where he has a marker in the old part of the grounds.

Marker showing where Muybridge's ashes are buried at Woking Crematorium.

Muybridge had bequeathed his projection machines, including his original zoopraxiscope, nearly all his zoopraxiscope discs (68 of the surviving 71), the biunial lantern that he used with the zoopraxiscope when lecturing, his lantern slides, his panorama of San Francisco, his albums of prints, and his scrapbook of newspaper cuttings, as well as money, to the recently built Kingston Public Library with its attached museum. This hugely important holding has continued to grow, through the acquisition of scholarly work; key items from it are on show there still (see "Eadweard Muybridge: Defining Modernities").

Bibliography

Barber, Stephen. Muybridge: The Eye in Motion. Chicago: Solar Books, 2019.

Braun, Marta. Edweard Muybridge. London: Reaktion Books, 2010.

"Edweard Muybridge, 1830-1904: Commemorating a Centenary." Kingston Museum and heritage Service, 2004 (leaflet available at the museum at that time).

"Edweard Muybridge: Defining Modernities." Kingston Museum and Heritage Service. Web. 30 May 2022.

Hendricks, Gordon. Edweard Muybridge: The Father of the Motion Picture. New York: Grossman (Viking), 1975. [This contains a useful chronology, pp.243-44.]

Schaaf, Larry J. "Muybridge, Eadweard James [formerly Edward James Muggeridge] (1830–1904), developer of motion photography." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 30 May 2022.

Warner, Jennifer. Murder in Motion: The Strange Life of Photographer (and Murderer) Eadweard Muybridge. Anaheim, California: Bookcaps, 2015.

Created 6 June 2022