Claude Montefiore

s Judaism “reformed” in the nineteenth century, especially driven by modern thought from Germany and brought to America and elsewhere, British Jews also experienced a wave of reformation. The second wave, following the establishment of a Reform presence in England, was driven by two affluent lay people: Claude Montefiore (1858-1938) and Lily Montagu (1873-1963). Daniel Langton’s excellent biography of Montefiore provides insight into this unusual character. Montefiore’s education and pursuits as a privileged and wealthy English Jew from a distinguished family led him to explore church as well as synagogue. His second wife Florence Ward was a convert to Judaism, although Montefiore waited until after his mother died to marry someone not born a Jew. He proclaimed that interfaith marriages threatened Jewish continuity; yet when his sister married a Christian in 1884, he supported her choice. Montefiore nevertheless argued against mixed-religion marriages throughout his life. His leadership led to the establishment of the Jewish Religious Union for the Advancement of Liberal Judaism (J.R.U.) in 1902. He became first president of the Liberal Jewish Synagogue when it was declared in 1910 and the first president in 1926 of the World Union for Progressive Judaism. His life was defined by interfaith dialogue.

Langton argues that Montefiore’s defense of Christianity is really an apologia for a very progressive form of Judaism insofar as he had absorbed and identified with liberal Christianity. Montefiore is a critical figure of his age because of the way he complicates Jewish identity. On the race versus religion question, Montefiore saw himself as an Englishman of the Jewish persuasion. He criticized those Jews who denigrated liberal Christianity, instead choosing to focus upon what Judaism shared with that faith. Politically he opposed Zionism, fearing not only that it would create doubt about Jews’ allegiance to their own countries but also that it stood in the way of the development of a universalist Jewish theology. Montefiore wished to distinguish between Jews and “Israelites” -- the one racial, the other religious.

Montefiore based his understanding of Judaism upon two qualities that left him vulnerable to criticism. His religion was about faith (i.e., belief in God) and love. Montefiore’s favorable speech about Christianity made many Jews uncomfortable; his focus on love provoked allusions to clichés that Judaism was more concerned with justice. Like the Classical Reformers of Judaism in America and their German teachers, Montefiore understood chosenness of Jews by God in terms of service: in particular, that Liberal Judaism could act as a unifying force to accomplish a universalist task. Montefiore claimed that Christian western civilization belonged to Jews as much as to Christians, since the literature of the New Testament is Jewish. He spoke as a Jew and a lover of Judaism: its defender, not detractor. Reform Jews thought that Christians were right in those pejorative accusations about Orthodoxy, but not in criticisms of their modern version of Judaism.

Victorian liberal protestants had begun to concentrate on the human Jesus more than the Divine Christ, focusing on ethics and high morality, which appealed to liberal-minded Jews. Montefiore supported missionary activity as a counter to Christian views of Judaism as a particularist religion and promoted a universalist Liberal Judaism. Combining critical techniques of New Testament studies with knowledge of rabbinic literature, Montefiore, like later Jewish writers, approached Jesus with a view to enriching his own understanding of Judaism. However, in contrast to Abraham Geiger (1810-1874) and others, Montefiore believed that Jesus was in fact special, unique, and different from his contemporary Jewish teachers. If the argument to reclaim Jesus as Jewish was an affirmation of Judaism’s richness, counter to nineteenth-century Christian scholarship on the uniqueness of Christ, Montefiore valued what he saw to be his reforms of Judaism. Like Oscar Wilde and other iconoclastic figures of the fin de siècle, Montefiore identified with Christ.

Lily Montagu

lthough it is difficult to distinguish their contributions without gender inflections, Montefiore had an important collaborator in Lily Montagu, whose work with him led to their comparison to the Christian saints Francis and Clare. Montagu’s biographer Ellen Umansky maintains she was driven by inner piety and faith to reform English Judaism. Her similarities in drive and devotion to Victorian Christian women, as well as to the fin-de-siècle New Woman, make her a unique and complex figure. For Montagu, the Orthodoxy with which she had been raised was external, neither beautiful nor meaningful: a hindrance to development of true religious faith. Her goal was to be fully Jewish and fully spiritual without being an Orthodox Jew: to identify being Jewish with the spirit of the modern age.

Montagu’s authority is both an example and a special case. From the mid-nineteenth century in Germany, Reformers such as Geiger maintained that men and women should have the same religious obligations. This way of thinking eventually led not only to confirmation rather than bar mitzvah, but also to women counting in a minyan (prayer quorum) and to joint seating in synagogues. Beginning in America in 1846, I. M. Wise admitted girls to his synagogue choir. Later women were encouraged to attend his Hebrew Union College, although they did not pursue ordination. The argument was that ordination to the rabbinate was inconsequential as long as women recognized their capabilities of holding such offices.

Umansky points out the Victorian nature of Montagu’s devotion: that she was part of a world that turned to Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning, rather than the Talmud, in searching for values; often because they felt that Judaism no longer spoke to them or to their generation. Others, including Montagu’s Orthodox father found the moral overtones of Thomas Carlyle and Matthew Arnold uplifting. Montagu’s Victorian sense of personal mission – a belief that her enthusiasm was required by God – resonates with George Eliot’s religion of humanity. Victorian devotion identified God as a power not ourselves that makes for righteousness with holiness and morality. Religious life is work and duty: serving God by serving others.

Reading Montefiore led Montagu to reconcile with Judaism, engendering a plan to make Judaism compatible with “true religion.” Real religion for the Victorian Montagu involved the personal experience of the Divine. This devotional theology is both mystical and experiential; and, as the Victorians understood it, situated within life in the world, not outside of it. Montagu’s theology resembled that of her Christian analogs, but she discovered it within Judaism. Through reading Montefiore, she found the personal religion she sought: a relationship between the individual Jew and God, wherein it was also possible to find the truths of Browning, Eliot, and Arnold in Judaism. While her life reads like that of many Victorian Christian ladies, Lily Montagu (who lived into the second half of the twentieth century) remained firmly devoted to Judaism. Following the Anglican idea of a Broad Church, Montagu likewise imagined a “Broad Synagogue” wherein her parents’ Orthodoxy and her Liberalism were just different manifestations of the same Jewish essence.

Like many devout Victorians, Montagu was convinced that she had been called by God. She had an awakening that formal religion would become the spiritual force in her existence; after recovery from a nervous illness, she concluded that her relationship with God would define her life. What followed was a lifetime of writing and preaching, which she began at the time of the First World War at the Liberal Synagogue, through the encouragement of Rabbi Israel Mattuck (1883-1954). A thorough universalist, Montagu experienced a literal vision of a Jewish service at a temple in which people of all races and religions worshipped together. On purely religious grounds she opposed intermarriage. She nevertheless rejected peoplehood and nationality, believing it possible for a non-Jew to enter into the Jewish community. Montagu enthusiastically accepted converts, whom she believed were more Jewish than born Jews (who needed some motive to become religious). She administered the West Central Jewish Congregation, where she officiated weekly and regularly preached.

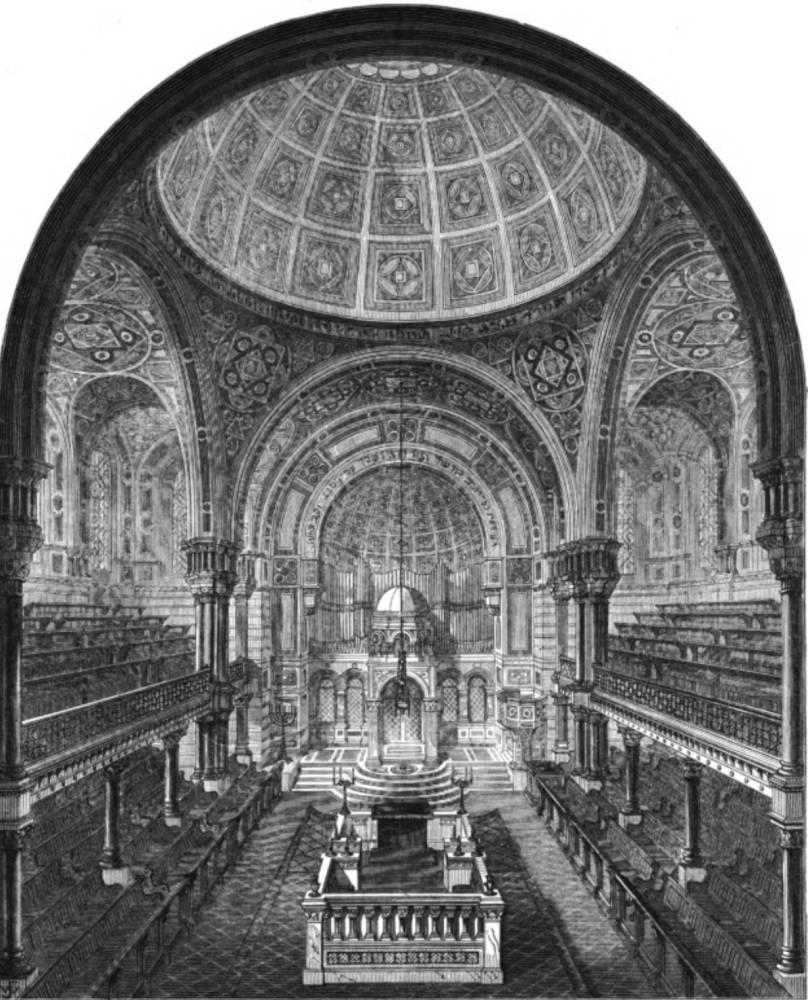

The West London Synagogue (1879 Illustrated London News). Click on image to enlarge it.

Montefiore and Montagu were active in a British culture that had already felt the effects of modernization. The Jewish Chronicle was launched in 1841, Jews’ College (now the London School of Jewish Studies) was founded 1855, and in 1888 the Jewish Quarterly Review began publishing. In 1841 the West London Synagogue of British Jews (Reform) was established. Until 1849, a herem (excommunication) was issued by Orthodox authorities against its members, who could not be buried in the Jewish cemeteries in which their parents were buried. Despite the movements towards liberalization, few British Jews were prepared to hear the kinds of proclamations that Montefiore and Montagu made. For example, Montefiore delivered an eloquent and sentimental prose-poem on Jesus in his 1918 Liberal Judaism and Hellenism. Montefiore articulated Jesus as the greatest Jew who ever lived: perhaps the greatest human who ever lived, but not Divine. Victorian liberal Christian discourse on Jesus the man permeates Montefiore’s argument — except, rather than using it to disprove some points of Christian belief (as liberal Christians and Jews did), Montefiore deploys the story in the service of Liberal Judaism.

Montefiore made his argument in his 1910 The Synoptic Gospels, which argued that a failure to read or study the Gospels is an educational lack for Jews. There Montefiore promoted the so-called prophetic Judaism put forth by the Classical Reformers, taking it to the logical extreme of the radical universalist wing. He felt that Jesus never intended to found a new religion, and that liberal Jews and progressive Christians had more in common with each other than with their respective traditions. However differently read and understood, Jesus might still be the meeting point of Liberal Judaism and Unitarian Christianity.

Montefiore refused to let the history of Christian anti-Semitism remove the significance of Christianity for Jews. Within a paradigm of ethical monotheism and providential suffering (even Jewish sacrifice), Jesus may have been the prophet for the Gentiles, yet he spoke from Judaism. Even as Montefiore located Jesus within the prophetic tradition, he maintained his uniqueness. In Liberal Judaism and Hellenism, Montefiore focused on the universalist aspects of Pauline thought and combined it with rabbinics to formulate his ideal of Liberal Judaism. He concluded that in the development of Reform Judaism, Liberal Judaism is Pauline: inextricably shaped by Christian thought in the western world in a theology of universalism even as the ancient teachings contain its timeless message. As Montefiore and other progressive Jews were deracializing Judaism, focusing on religion instead of nationalism, he named St. Paul as a model (if an inadequate one) for their project. He judaized Pauline thought even as he reformed rabbinism. In his view, Pauline Christianity, not liberal Judaism, is the one guilty of particularism by focusing on belief in Christ. The rational and fully universalist answer is to be found in Montefiore’s faith: a rational yet heartfelt religion for all.

In his 1923 The Old Testament and After, Montefiore returned to address the problem of Jewish nationalism or particularism. At this point, as he continued to cling to a strictly religious understanding, he clearly addressed the larger embrace of Zionism within the Jewish world. Even as a necessity for refuge in Palestine had become more imminent given the pogroms in eastern Europe, Montefiore could not let go of the idea that a distinct Jewish nationalism would dilute the religion of Judaism and give power to anti-Semites who refuse Jewish emancipation in the diaspora. For him, Judaism was a progressive religion for a reforming West. Montefiore, who remained an idealist, supported any efforts to make Jews safe (not to mention comfortable and emancipated) in the countries in which they lived. He affirmed that Sunday sabbath observance, if done prayerfully, could revive, not de-judaize, Jewish life. Rather than endangering Jewish authenticity, learning from other faiths (specifically Christianity) might enrich Judaism.

Of course, Montefiore was among those who have looked at Christianity and in fact incorporated much that he learned into his expression of Liberal Judaism, maintaining that doing so would not detract from Jewish authenticity. He advocated that Jews are the best readers of the New Testament, since it was written by Jews; and that, as one finds both insights and errors in the Talmud, so can the Jew find insights and errors in Christian scripture. Rabbi Israel Mattuck followed this argument in his 1947 The Essentials of Liberal Judaism when he suggested that Jews must take particular interest in Jesus. There Mattuck speaks poignantly and still idealistically in a post-Holocaust voice. That such hope could endure after the Shoah (catastrophe: the Holocaust) is a testament to the devotion of belief in this mission of Judaism.

Throughout his writings, Montefiore wrestled with the problem of Jewish purity: the desire to claim a breadth of what constitutes Judaism and refrain from tests of authenticity based on racial identity. His 1912 Outlines of Liberal Judaism engaged the same sciences that anti-Semites used: in his case, to make religious, anti-nationalist Jewish arguments. In his attempts to articulate a theology that treated all humanity equally, Montefiore was not comfortable with the idea of a national God. As late as his 1937 edition of Liberal Judaism and Hellenism, he continued to see nationalism and religion as mutually exclusive. In a purely religious sense, he feared fundamentalism. Even in the mid-1930s, as Nazi power in Germany continued growing, Montefiore saw no good in political Zionism and felt that religious Zionism had been outgrown. For better or worse, the radical Montefiore anticipated many of the problems that the land of Israel would later face with regard to the breakdown/authorization of Jewish identity with respect to Jewish civil and religious law. A strange bedfellow for the ultra-Orthodox anti-Zionist on the far right, Montefiore understood religious nationalism as idolatry. Lily Montagu, in an unpublished sermon, provided a tempered version of Montefiore’s ideals. Near the end of her life, Montagu led the World Union that she helped found. Its mission today includes the promotion of Progressive Judaism in Israel.

Bibliography

Langton, Daniel R. Claude Montefiore: His Life and Thought. Portland(OR): Vallentine Mitchell, 2002.

Umansky, Ellen M. Lily Montagu and the Advancement of Liberal Judaism. Lewiston (NY): Edwin Mellen Press, 1983.

Last modified 12 June 2018