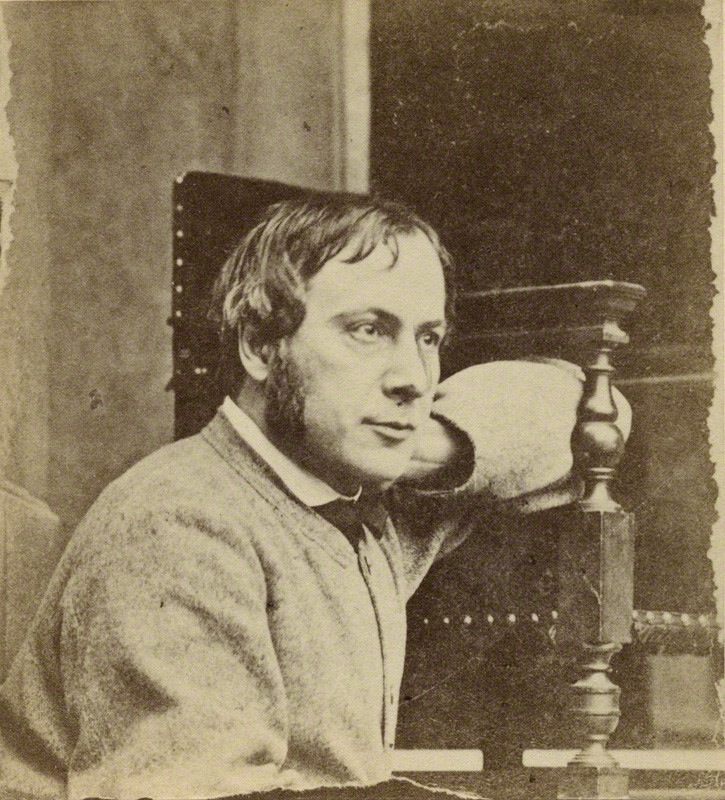

Alfred George Stevens by an unknown photographer: small albumen print on a card mount, 1867, given to the National Portrait Gallery by James Gamble, 1909. © copyright National Portrait Gallery, London, by kind permission.

Alfred George Stevens (1817-1875) was born in Blandford Forum, a small market town in Dorset, into "humble circumstances," as one art critic puts it ("Alfred Stevens"). His father was a painter of signs and/or heraldic devices, and house decorator, and the boy left the village school when he was ten to help him in the workshop. His talent brought him to the notice of the local rector, the Hon. Rev. Samuel Best, who sent him to study in Italy in 1833. Although he was only sixteen when he left, he travelled widely there, and developed a passion for Italian art. He studied mainly in Florence and Rome, and at the beginning of the 1840s was employed in Rome as an assistant to the highly regarded Danish sculptor, Bertel Thorvaldsen.

After returning home in 1842, Stevens was given a tutorship at the New School of Design at Somerset House, which he held from 1845-47. From 1849-95, he worked for C. R. Cockerell on St. George's Hall, Liverpool, 1849-54. He also made designs for H. E. Hoole & Co., Sheffield, from 1850-57. This was a company specialising in bronze and metalwork, and during that time he also designed twenty-five lions for the British Museum's boundary railings (later dismantled). Then came his one major public commission: in 1856 he began work on the Wellington Memorial for St. Paul's Cathedral (twelve of the British Museum lions found their way to the railings around it). He would not live to complete his masterpiece. From 1860 he also worked on the decoration of Dorchester House, Park Lane for Sir George Holford (see British Sculpture 1850-1914).

Despite the recognition he received, Stevens's life was not an easy one. The The Times obituary includes high compliments but also also leads up to the startling statement that he "left neither wife, nor children, nor riches, but the name of one of the greatest decorative artists insanely devoted to his art." On the one hand, praise is poured on the "two groups of the Wellington Monument — Truth plucking out the tongue of Falsehood, and Valour triumphing over Cowardice." These, it seems, would "achieve for him a lasting fame among the decorative artists of modern times." But on the other hand, Stevens's painstaking perfectionism is seen as pathological: "He was never satisfied with his work," and "would destroy model after model and sketch after sketch while he was eating only a crust of bread." Moreover, says the Times columnist, it was hard for him to part with his work, which he always felt could be improved. Such quirks, if that is what they are, are common enough among artists of all kinds, but they evidently caused him problems. His admirers may have valued his "laborious prodigality of time" (Stannus 8), but the Office of Works, in its dealing with him over this commission, did not.

In fact, the progress or otherwise of the Wellington Monument became a saga, which continued even after his death. Later biographers placed the blame squarely on the Office of Works itself, especially on its niggardliness: according to a writer in The Art Amateur,

The genius of a sculptor, some of whose work has been not unreasonably compared with that of the great Michael Angelo himself, was but half understood by his countrymen, who allowed him to sacrifice his hard-earned savings and indeed his life itself in the attempt to complete a public monument for the execution of which Parliament had voted an insufficient appropriation. ["Alfred Stevens"]

The Office of Works's dealings with the sculptor "make a shabby story," says the reviewer of Kenneth Romney Towndrow biography of Stevens (Constable 244).

Ironically, this "shabby story" had a certain advantage for Stevens's reputation, turning both the monument and its designer into "a major artistic cause célèbre," with Stevens assuming "in the public mind an unique stature, as a sculptor, that is still pervasive and, more important perhaps, was of significant effect on the generation of sculptors coming to maturity in the last quarter of the century" (Read 276). by representing artistic values up against bureaucracy and conventional expectations, Stevens not only had an impact on the emerging New Sculpture, but on the applied arts in general. With his "passionate belief in the integration of art and design — his motto was 'I know of but one Art' — he could also be seen to foreshadow the ideals of the arts and crafts movement" (Stocker).

Stevens died on 1 May 1875, possibly by his own hand (see Stocker). If so, his early death seems especially tragic. He was buried in the Western part of Highgate Cemetery. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Related Material

- Stevens's grave in Highgate Cemetery

- Alfred Stevens, An Appreciation,” by Frederick Wedmore (1890)

Bibliography

"Alfred Stevens." The Art Amateur, Vol. 4 (1 March 1881). Internet Archive. JSTOR Early Journal Content. Web. 22 May 2014.

"The British Museum Lion." British Museum. Web. 22 May 2014.

British Sculpture 1850-1914. A loan exhibition of sculpture and medals sponsored by The Victorian Society. London: Fine Art Society, 1968.

Constable, W. G. "Alfred Stevens: A Biography with New Material by Kenneth Romney Towndrow" (Review). The Art Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 3 (September 1941): 242-244. Accessed via JSTOR. Web. 22 May 2014.

Read, Benedict. Victorian Sculpture. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1982.

Stannus, Hugh Hutton. Drawings of Alfred Stevens. London: George Newnes, 1908. Internet Archive. Uploaded” by the California Digital Library. Web. 22 May 2014.

Stocker, Mark. "Stevens, Alfred George (1817-1875)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 22 May 2014.

"The Wellington Monument — Mr. Alfred George Stevens." Times. 4 May 1875: 8. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 22 May 2014.

22 May 2014