[This following comes from the first chapter of Gertrude Jekyll's Old English Household Life (1925), some of the material of which previously appeared in her 1904 volume, Old West Surrey. I believe the photographs are all hers. GPL].

The fireplace and chimney as we now have them were unknown in ordinary dwelling houses until the sixteenth century and were only then beginning to be general. Some such fireplaces were only in the greater castles and palaces, and even in some of these buildings still existing, the ancient fireplace, as at Penshurst, remains in the middle of the floor of the great hall, with its heavy iron coupled andirons to hold up the logs. The alternative to this was an iron brazier for burning charcoal or peat. The smoke found its way out as it could, usually through a hole in the roof or by interstices in thatch or tiling, or any openings as of doors or windows. The timbers of the roof became coated with soot, and in the case of a leaky roof of thatch the wet streamed down laden with black. Though the smoke of wood or peat is more tolerable than that of coal, yet the conditions of living must, to our modern ideas, have been full of discomfort. They were the same, in fact, differing only in degree, as those of the dwellers in the circular huts of the ancient Britons of which there are remains, for then also the hearth for the fire was in the centre and the sleeping places all round; the sleepers lying with their feet to the fire. Even in the great hall of the castle the arrangement was the same, of a central fire and a general sleeping place surrounding it.

A "Reredos" from the Shetland Islands. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

The most primitive form of fireplace may even now be seen in the Orkney and Shetland Islands, where it consists of a central hearth and a rising lump of stone, slightly hollowed in one face, that forms a backing to the fire. An iron hanger to hold a pot is suspended from above [See image at right]

The first advance towards a chimney was in the later part of the thirteenth century, when the hole in the roof was covered with open boarding in the form that is still known as louvres ; they were made of horizontal slats of wood, fixed apart and set diagonally in order to throw off the wet, and roofed in at the top. Later, when these were of some size they were treated architecturally and formed handsome features on the building. Several good examples remain, and though they are no longer needed for their original purpose, they are treasured for their

When built chimneys came to be general, the fireplace was still of a very simple form. As wood was the usual fuel, the only alternative being either deep-bedded or surface peat, the place for the fire was built wide and deep, often large enough for stout oak seats to be built in on each side. In Sussex and Surrey and the home counties generally, it was called a "down" hearth. There are still some in use in remote and moorland districts, and very pleasant they are on winter evenings when fuel is in plenty and when the enclose'd space of the wide chimney opening is continued into the room by an opposite pair of long, high-backed settles, and sometimes by a curtain that draws right round,

It was frequent, in the region of the iron foundries of the Weald of Sussex, as well as farther north, for the cottage hearth to have a flooring of a thick cast-iron plate with a course of brick or stone supporting it to right and left, leaving a space in the middle under the hottest of the fire. Whether this space was actually used for baking seems uncertain, but in any case it was a good place for warming plates or keeping food hot.

Baking was done on the down hearth by laying an earthen pan bottom up over the loaf or cake and heaping hot ashes all round. In these fires it was usual to have one large heavy log at the back, and it might be weeks before this was burnt through. The ashes were left in a goodly heap, and there were always in the morning a few bits with fire still smouldering that could be blown up into flame with the bellows. Meanwhile, the whole hearth kept warm and was in a favourable state for encouraging the new morning's fire.

In farm houses and many of the better class cottage there was a brick oven for baking, shown in Figs.'91, 92. It was built with a brick floor and arched like a tunnel and had an iron door. A faggot was set alight within and when it was burnt and the ashes raked out it was right for baking. Old people will remember the little atoms of charcoal that stuck to the bottom of the loaf.

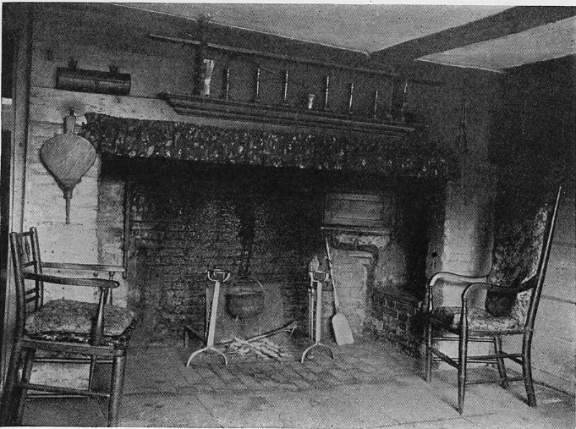

At Lodsworth, West Sussex [Figure 8 in the original]

The illustrations show the general development of the farm or cottage fireplace. At Fig. 8 we see the simple "down" fire in a farm house in West Sussex. The fire is on the brick hearth, level with the room floor; it was more often raised a step, which is better both for draught and for getting at the cooking. There is a plain iron fire- back and a pair of cup-dogs. The iron pot is slung over the fire by a long hook leading to a hanger from a chimney crane; an oak beam stretches across, carried by the jambs to right and left. Above is a moulded shelf and a spit-rack, both of later date than the original building, but still of respectable age, for they go well back into the eighteenth century. A grand old spit rests upon the rack, evidently an old family possession ; it is kept bright by the careful housewife ; the hooks at the backs of the cup-dogs show where it rested in cooking the great joints of meat. On the shelf are more family treasures ; three pairs of brass candlesticks and a brass mortar, and beyond them, on the wall, a pair of brand tongs. To the left are the sheet iron candlebox and the bellows. A seat is notched into the wall on the right.

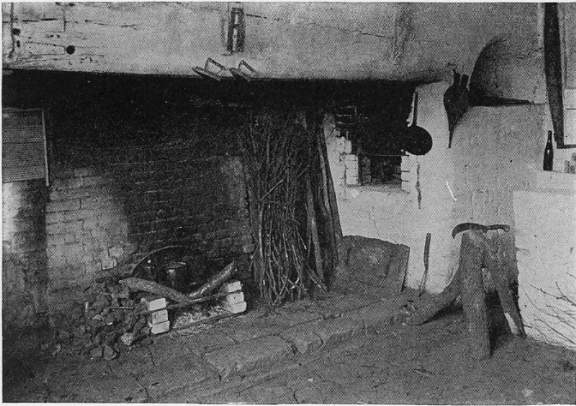

At Lodsworth, West Sussex [Figure 9 in the original]

The next illustration (Fig. 9) shows a Kentish back kitchen. In this case the hearth is raised; the fire has a good cast-iron back, probably from the old Sussex ironworks. There is an iron plate at the bottom and an arrangement of loose fire bricks and iron bars. The fire is mainly of wood, but a heap of coke or clinker at the side shows that other fuel was also used. The brick oven is to the right; its iron door with two handles stands against the wall below.

The illustrations show the general development of the farm or cottage fireplace. At Fig. 8 we see the simple "down" fire in a farm house in West Sussex. The fire is on the brick hearth, level with the room floor; it was more often raised a step, which is better both for draught and for getting at the cooking. There is a plain iron fire- back and a pair of cup-dogs. The iron pot is slung over the fire by a long hook leading to a hanger from a chimney crane; an oak beam stretches across, carried by the jambs to right and left. Above is a moulded shelf and a spit-rack, both of later date than the original building, but still of respectable age, for they go well back into the eighteenth century. A grand old spit rests upon the rack, evidently an old family possession ; it is kept bright by the careful housewife ; the hooks at the backs of the cup-dogs show where it rested in cooking the great joints of meat. On the shelf are more family treasures ; three pairs of brass candlesticks and a brass mortar, and beyond them, on the wall, a pair of brand tongs. To the left are the sheet iron candlebox and the bellows. A seat is notched into the wall on the right.

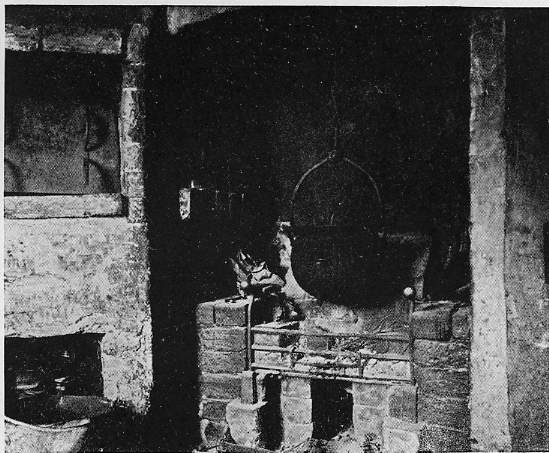

Cottage Fireplace and oven, Wigmore, Herfordshire [Figure 10 in the original]

The next example, from Herefordshire (Fig. 10), shows the older large space contracted by a wall one brick thick to the right, and a built-up fire- place with a wrought-iron front of three bars. It is interesting to note in this ironwork, a recollection of fire dogs, in the slightly swan-necked upright ends, capped by small balls. The iron pot still swings from above, showing that there must be a firebar across the chimney.

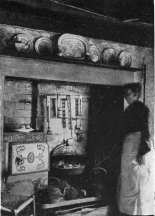

Left (Figure 13): Turf fireplace in a Yorkshire farm-House. Middle (Figure 14): A Yorkshire farm fire. Cake baking with burning peat on cover. Right (Frontispiece): Ingle Nook, Welsh Farmstead. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

A further development, this time from Yorkshire (Fig. 13), shows a fireplace of later date built into the smaller width now usual, but with the fire still on the hearth on an iron plate with a space underneath, much like what is usual in the older cottages in Sussex; but the advance is in having something of the nature of an oven or boiler with a moulded cast-iron front, though from the picture itself its use in this case is obscure. The fire is of peat. This fireplace may have been built in from an older and wider one ; the cupboard door on the right showing that there must be a recess within, that would be accounted for by the remainder of the older and wider hearth-place. Another example from Yorkshire (Fig. 14), with a cast-iron fronted oven, shows a clinging to the older ways, for there are still the chimney crane and a number of different hangers. The mistress is here baking a cake on a peat fire; the pan has an iron lid on which she has put a number of pieces of glowing peat, thus giving heat above ,and below, after the French cook's manner of braising with feu dessus-dessous.

Another picture, from Wales (frontispiece), shows a nearer fore-runner of the modem kitchener, with a coal fire, an oven on one side and a boiler on the other. Even in this the crane still survives and holds the kettle. It was an error in taste to cover the arching beam with wall paper, but probably its ancient roughness offended the house-proud sensibilities of the good housewife. The chimney shelf holds a handsome teapot, a cake mould, and some brass candlesticks. Suspended from the joists are two parallel bars, that, had they been in a back kitchen or some other cooler place than just before the fire would have been taken for a bacon rack; here they are no doubt used for airing sheets. On the wall of the recess to the right hang a variety of kitchen implements, all beautifully kept — tongs and shovel, frying-pan, chopper, meat saw, toasting fork, strainers and skimmers; also some of the master's gear — bridle bits and a large hooked spring balance.

Bibliography

Jekyll, Gertrude Old English Household Life: Some Account of Cottage Objects and Country Folk. London: B. T. Batsford, 1925.

Jekyll, Gertrude Old West Surrey: Some Notes and Memories. London: Longmans, Green, & Co, 1904.

1 February 2009