Transcribed and reformatted from an article in The Strand Magazine, Vol. IX (January-June 1895): 127-136 in the Internet Archive. You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them.] — Jacqueline Banerjee

T the present day, when ladies in bifurcated nether garments may be seen awheel in Piccadilly, or enjoying a cigarette in the smoking-room of their own club, it is no wonder that the pretty custom of sending valentines is fast falling into desuetude. In the days of Chaucer and Shakespeare, the charming, if fanciful, theory obtained that birds chose their mates on the 14th of February. Later on, shy maidens and laggard lovers took advantage of this uncertain object-lesson from Nature, and were emboldened to go through a form of betrothal on St. Valentine's Day, In the course of time, however, this ceremony was preceded by an exchange of fancy cards, on more or less shaky doggerel. Now, as it is not given unto every man to be a poet, there was clearly a brilliant commercial career before the man who would put on the market a quantity of passable sentimental verse, accompanied by appropriate designs — in a word, valentines as we know them.

FIG. 1 — The First Pictorial Valentine.

Here is one of the very earliest of these prints, published in 1827, and remarkable for its graceful simplicity (Fig. 1). The subject of the sailor and his lass, by the way, has served the valentine designer on more occasions than we care to count; nor is this surprising, in view of the fact that Jack has at all times loyally observed St. Valentine's Day. Indeed, we are quite satisfied that in the dock districts of London and Liverpool, the guileful retailer has a special tariff for sailors, whereby the latter are not only induced to pay double prices for a valentine that suits their fancy, but are also charged a comparatively large sum for a pipe or tobacco pouch which is introduced into the purchase, and which the dealer could never otherwise dispose of.

It may be interesting to mention here that this ingenious system of business reached the Midlands; and the Birmingham manufacturers hailed it as a Heaven-sent notion for pushing the sale of shoddy jewellery. They ordered hundreds of gross of sentimental valentines in boxes, stipulating that the design should include a piece of loose blue ribbon on which might be hung watches, engagement rings, pencil cases, and charms, such as only Birmingham can produce. The finished valentines were then retailed at audacious prices, and found wonderful favour in the eyes of persons of a utilitarian turn of mind.

FIG. 2 — Valentine designed by Kenny Meadows in 1832.

Artists of some repute soon turned their attention to valentines. Our next reproduction is from a design by Kenny Meadows, in 1832 (Fig. 2). At this time, comic valentines were unknown; people took their love affairs somewhat seriously, and paid so generously for pictorial love-letters, that manufacturers were enabled to employ first-rate artists. Simple though the design appears, this valentine of Mr. Meadows [127/128] sold at two shillings — a sum for which one can now buy a gorgeous and perfumed arrangement of silk and hand painted satin, artificial flowers, and gold and silver lace paper.

Novelties in valentines came but slowly. No departure from a somewhat sickly sentimentality was made until the "fourteenth" came to be regarded less seriously. Then came valentines containing a certain element of mechanical contrivance — a tongue of card-board, which, when jerked, caused the figures in the picture to move. We are enabled to show here the origin of this type, which dates from about 1840 (Fig. 3). The design consists of a church, of no known architecture; and, on folding back a flap, the recipient of the valentine has a view through the wall of this remarkable edifice, in which it appears a wedding is taking place. The minister's hand is raised in benediction, but the bridegroom seems to be a little ill at ease.

Left to right: (a) FIG. 3 — The first mechanical Valentine (about 1840). (b) FIG. 4 — Made for the Hyde Park Exhibition of 1851. (c) FIG. 5 — Sachet Valentine, 1855.

Valentines now became more elaborate and expensive. Here is a photograph of one specially made for the Hyde Park Exhibition of 1851 (Fig. 4). This valentine is still preserved in a massive frame by the manufacturers, Messrs. Goode Bros., of Clerkenwell Green. It is composed of thousands of leaves and beads, put together by hand ; it took the most skilful lady designers of the day about a fortnight to make, and it cost ten pounds. At this time the above firm used a thousand pounds' worth of artificial flowers in a week, solely for sentimental valentines. Satin was purchased in quantities of 5,000 yards at a time, and the annual bill for lace paper came to £3,400. A thousand a year was paid for [128/129] boxes, and small fortunes were spent in humming birds, birds of paradise, and dry perfumes, such as kegs of lavender powder, Tonquin bean, and orris root.

Fig. 5 illustrates the fashionable valentine of this period, which can only be described as a kind of satin pillow inclosed in a box, and perfumed and ornamented. Sending valentines of this sort to friends in the Colonies caused such an export trade to spring up, that single houses in Sydney and Melbourne soon began to send in orders for a thousand pounds' worth at a time. And very expensive, too, were these Antipodean valentines, the wholesale shipping terms in many cases being 200s. per dozen. Never again, we may safely predict, will valentines fetch such preposterous sums as were realized by the class to which Fig. 6 belongs.

FIG. 6. — Designed and made for the Ballarat Gold Fields.

The Ballarat gold fever was at its height when the Australian houses sent urgent messages to the London makers for a special "line" suitable for the gold-laden, improvident miners. As might [129/130] be expected, the designers set to work with amazing celerity, and produced an extraordinary valentine more than 2ft. long and inclosed in a shallow box. It was made up of artificial flowers and leaves, paintings on satin, and imitation gems. The gold-seekers paid from £10 to £25 each for these valentines, one of which is depicted in Fig. 6. The original belongs to Mr. King, of 304, Essex Road, N., who, we have no hesitation in saying, possesses the largest and most complete "valentine museum" in the world. Another curious and elaborate valentine, made with paper springs, was in great request half a century ago.

From this time we note the genesis of the comic valentine, and, curiously enough, the policeman figures in the very first.

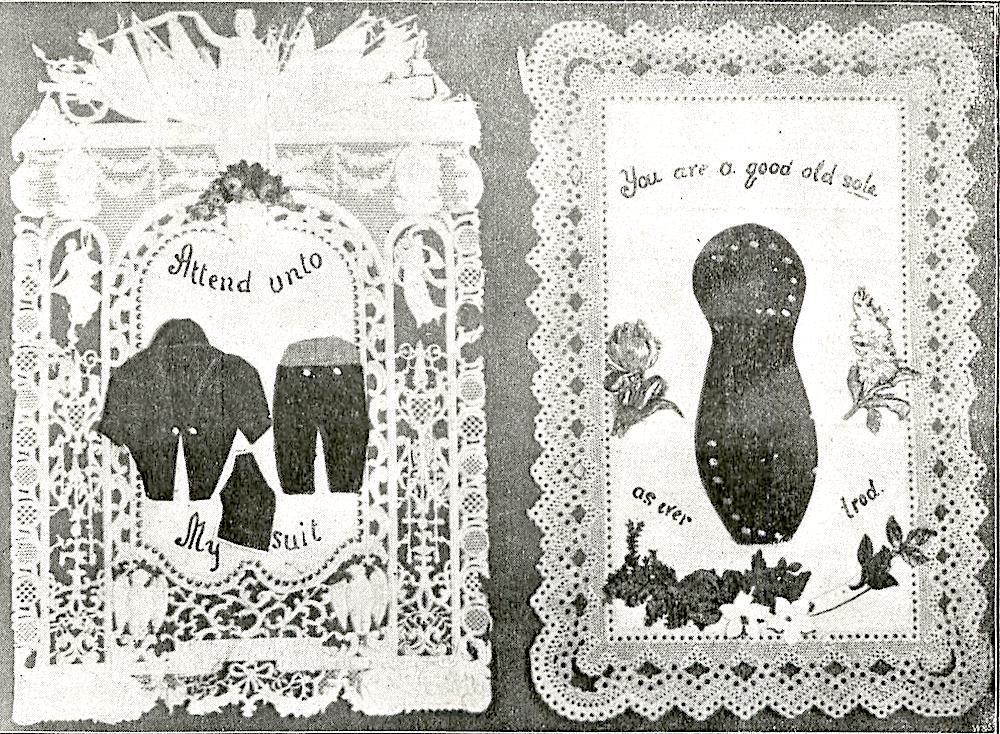

Left: FIG. 7 — An early comic policeman. Right: FIG. 8 — Novelties of Half a Century Ago.

Fig. 7 is a reproduction from a very old proof, the caricature being directed against exaggerated officialism; and Fig. 8 is a photograph of a page of one of Mr. King's innumerable albums. The "suit" thus quaintly depicted was described as being of "real cloth, cut by a tailor of repute." No sooner were these and similar humorous productions sprung upon an admiring public, than the designers cast about for further novelties, the result being that sentimental valentines were for a time somewhat neglected.

FIG. 9. — Another departure — caricatures in cloth.

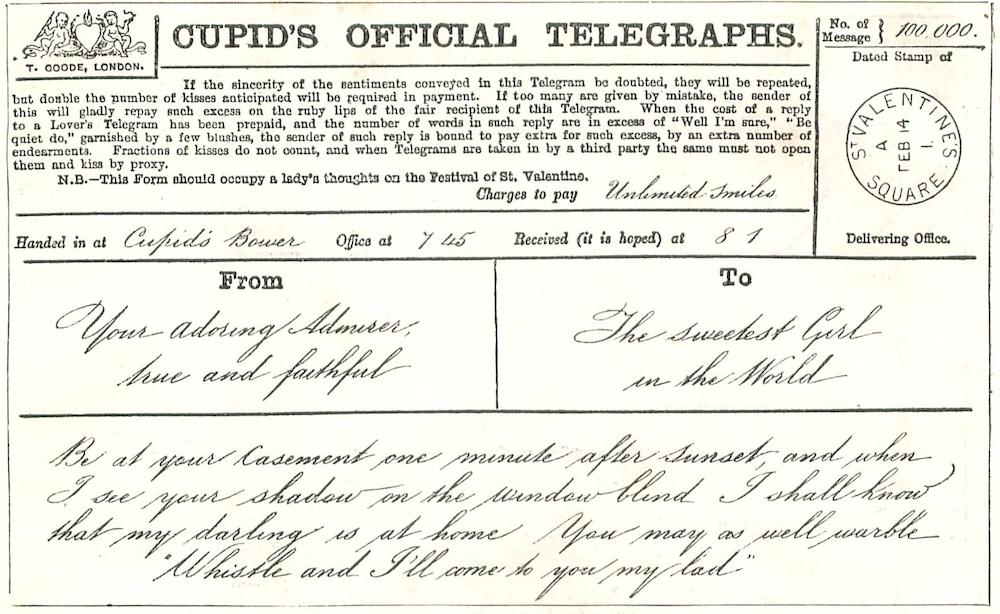

Fig. 9 shows another page from one of Mr. King's albums; and it should be noted that the whimsical figures are clad in real cloth, and that the wild-looking lady in the middle has a profusion of woolly hair, pasted on. "Cupid's Official Telegraph" (Fig. 10) was next hailed with delight as a novelty in valentines. It was sent out in a reddish-yellow envelope, and was altogether so close an imitation of the real article, that the then Postmaster-General set about binding the makers with red tape, and finally condemned the quaint little missive altogether. Not to be beaten, the designers instantly produced a Post Office Order, worded in the drollest possible manner. This was also withdrawn "by order," the authorities being [130/131] apparently quite destitute of humour; at any rate, one would have thought such small game as this unworthy of serious consideration by a Government department.

FIG. 10 — A telegraphic valentine.

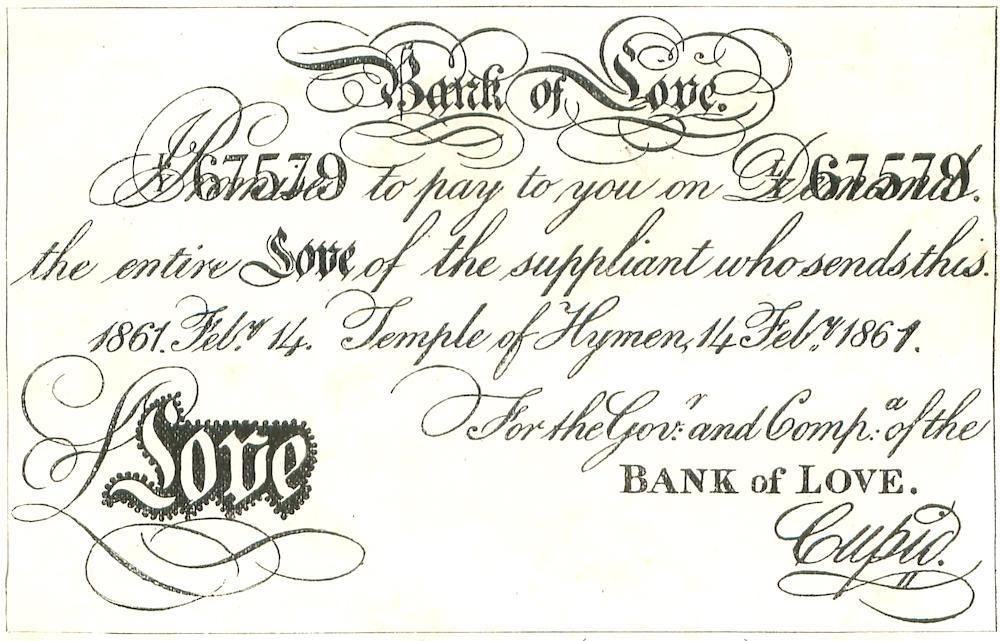

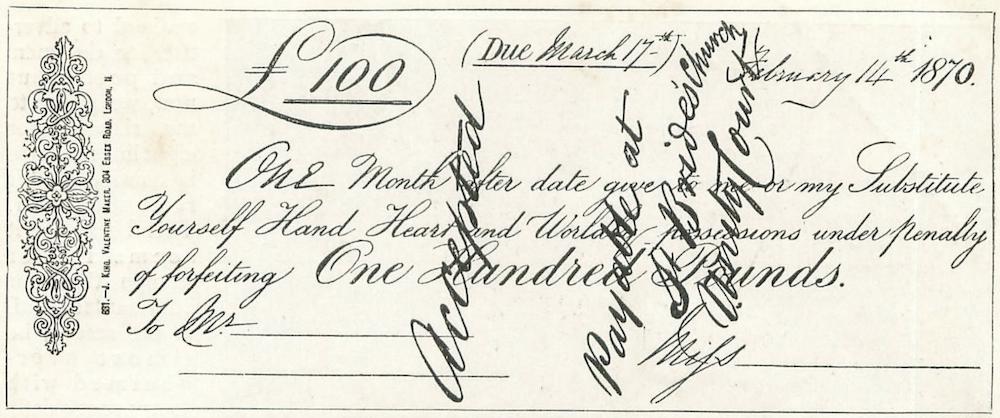

There must have been a tremendous demand, though, for this sort of valentine. Baffled by the Post Office, the ingenious designers turned their attention to the Bank of England, and issued thousands of notes on that world-renowned and long-established [131/132] institution, the "Bank of Love" (Fig. 11). The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, however, would have none of it, so she compelled the manufacturers to withdraw the notes from circulation. They were, therefore, "called in" in the orthodox manner.

Left: FIG. 11. — A note on the Bank of Love (reduced facsimile). Right: FIG. 12 — A trap for the unwary.

But the craze for commercial, official, and financial valentines was far from being dead. Swayed by the public, the makers continued to produce IOU's, jury and other summonses, promissory notes, official reports, writs, marriage certificates and licenses. School Board notices, wills, and acceptances. One of these latter is reproduced in Fig. 12, [132/133] and seems to have been specially designed with the view of expediting matters in breach of promise actions. Correctness of phraseology was observed with such scrupulous care, and paper and printing were imitated so closely in these valentines, that there can be no doubt of their being formidable weapons in the hands of practical jokers and unscrupulous persons. Will it be believed that change in hard cash was given for notes on the Bank of Love! Women were deluded by the strangely-worded marriage certificates and licenses, signed by Peter Tiethemtight, M.A., whose name is not to be found in Crockford; and busy men lost time and money over jury summonses, issued in the vague county of "Eithersex." This class of valentine gave place to the cheap comic prints, coarse and vulgar, as a rule, which we see in fancy shops prior to the now decadent "fourteenth," and which sold like wild-fire about twenty-five years ago.

Practically, there is but one firm left in the valentine trade, namely, Messrs. Goode Brothers, of Clerkenwell. The astonishingly rapid decline of the valentine within the past ten years brought ruin to many a wholesale manufacturer, to whom the trade was worth perhaps £20,000 a year, between the years 1870 and 1875 — the golden age of the valentine. At this period a single maker would keep six designers and eighty girls employed on valentines all the year round. Rice paper from China was bought by the shipload; plush, in wholesale quantities of 9,000 yards at 2s. per yard; and silk fringe, from Coventry, in bales of a hundred gross of yards. Twenty years ago, too, the big valentine dealer's turnover was a thousand pounds a week during the three months of the season; and in his workrooms a quarter of a ton of the finest white gum disappeared in the dainty trifles. Four well-paid male artists designed the "comics" — mainly trade skits and domestic incidents — and these were reproduced on 1,500 reams of paper. The machines were kept going night and day, turning out a million caricatures a week, of which some 5,000 gross were dispatched to Australia by sailing vessels in May and June. From a hundred to a hundred and thirty different comic designs were produced every year, and one house would have five smart "commercials" showing the pattern-books to retailers in all parts of the kingdom.

When one knows these things, it is extremely interesting to listen to the great wail that goes forth from whilom valentine makers. "Valentines belong to the past," say they; "therefore we have given up making them." One is then referred to Messrs. Goode Brothers for practical information; thither we went for the purpose of seeing how valentines are made. It seems that plush, satin, lace paper, fringe, and sachet powder are still bought wholesale, but in sadly reduced quantities. There is left but one solitary lady designer, and she must have ready two sets of about fifty different designs of sentimental valentines in the month of September, the retail prices to range from 1d. to 5s. One set, packed in trays, is taken away by the traveller, and according to his reports large quantities of certain designs are promptly put in hand to be made. The second set is retained at head-quarters for guidance. Nor must we omit to add that, in many cases, scope is left in the design for the introduction of such foreign matter as cheap jewellery and the superfluous stock of fancy dealers.

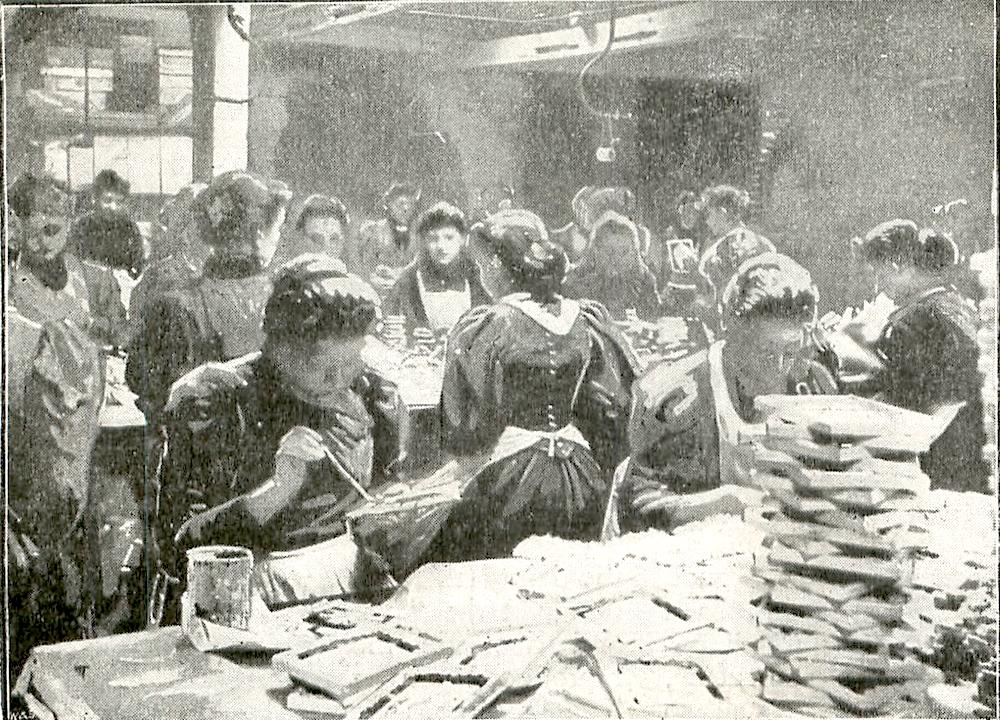

Left: FIG. 13. — The "sentimental" workroom. Right: FIG. 14 — "Comic" designing room.

Our photograph (Fig. 13) shows the interior [133/134] ol the "sentimental" workroom. The "hand-paintings on satin" which mark the superior article are reeled off at a perfectly amazing rate by outside lady artists, who earn about 25s. a week at the work. This is as it should be, seeing that for each separate work of art the sum of three farthings is paid. As a rule there is a church, with a pond in the foreground bordered with a few straggling rushes, and over the surface of the water a small flock of strange birds are hovering. During our investigations, by the way, we noticed but few of these "hand-paintings" without the birds.

"They are done in a moment and are so effective," was the curious comment of the forewoman. The sheets of satin given out to lady artists are folded into squares, and measure 15 in. by 12 in.

The rates of pay for comic and sentimental valentine poetry are not such as would tempt either Mr. Morris or Mr. Swinburne.

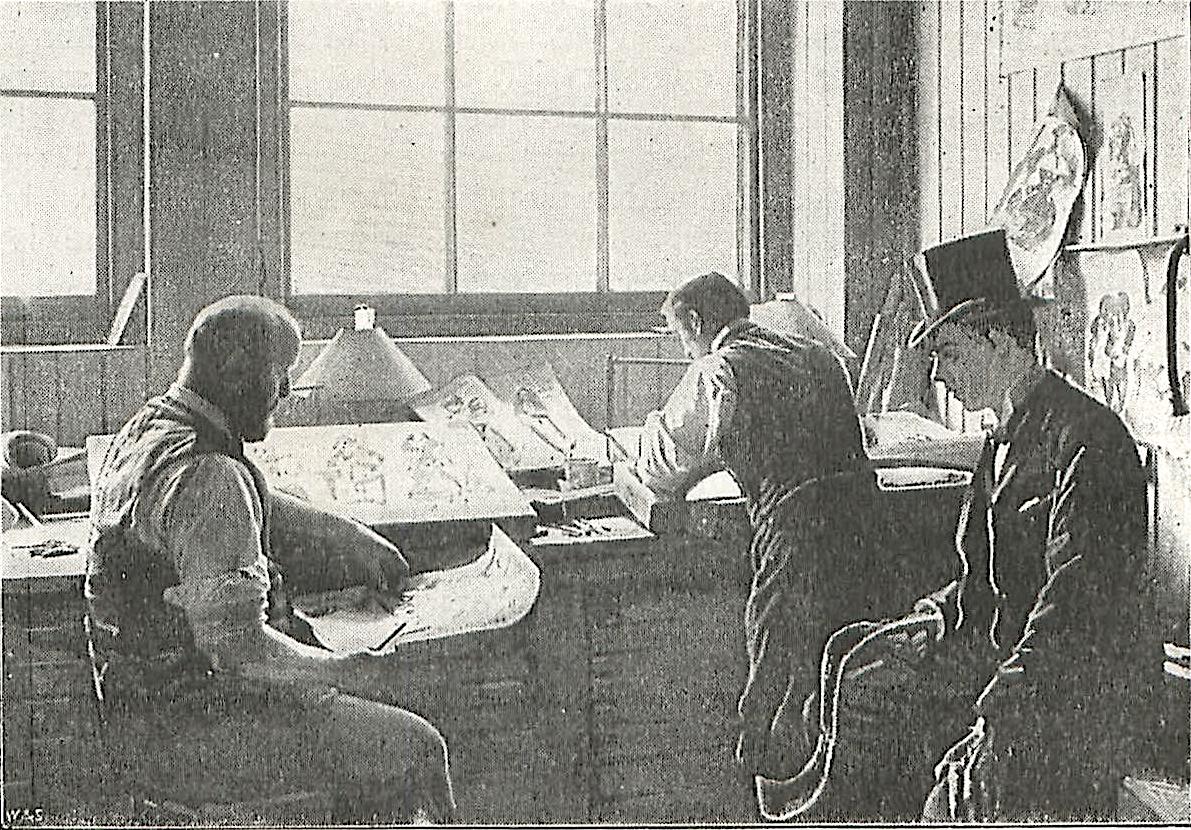

Time was, indeed, when the wholesale houses were constrained to advertise for designers and poets; but now, we grieve to say, sixpence for eight lines of verse is considered fair remunerati on. This being so, it seems rather strange that our informants should, in the season, be almost overwhelmed with poetry, sent chiefly by ladies, many of whom ask comparatively enormous sums for their rhymes, and never fail to mark even the veriest nonsense copyright, in aggressively bold characters. The firm whose premises we visited now keep but two comic valentine artists. These gentlemen produce about twenty different designs every season, and 10,000 copies of each design are made.

Our illustration (Fig. 14) depicts the interior of the comic designing room. The artist in the middle is drawing on stone one of his own designs; for each finished design he receives five shillings, or half a sovereign if he reproduces it on the stone. Comic valentine artists may not be as clever as Phil May, [134/135] or as careful in detail as Sambourne, but that they are observant and up-to-date will be seen from a glance in the stationers' windows at the beginning of February. It is interesting to note that there are certain districts which are dear to the designer's heart by reason of their having a marked partiality for a certain subject. For example, a comic valentine showing a stalwart athlete, who has apparently sustained serious bodily damage on the football field, is certain to command a great sale in the North of England, and especially in Lancashire. It is absolutely necessary, however, that the football itself be seen in the picture.

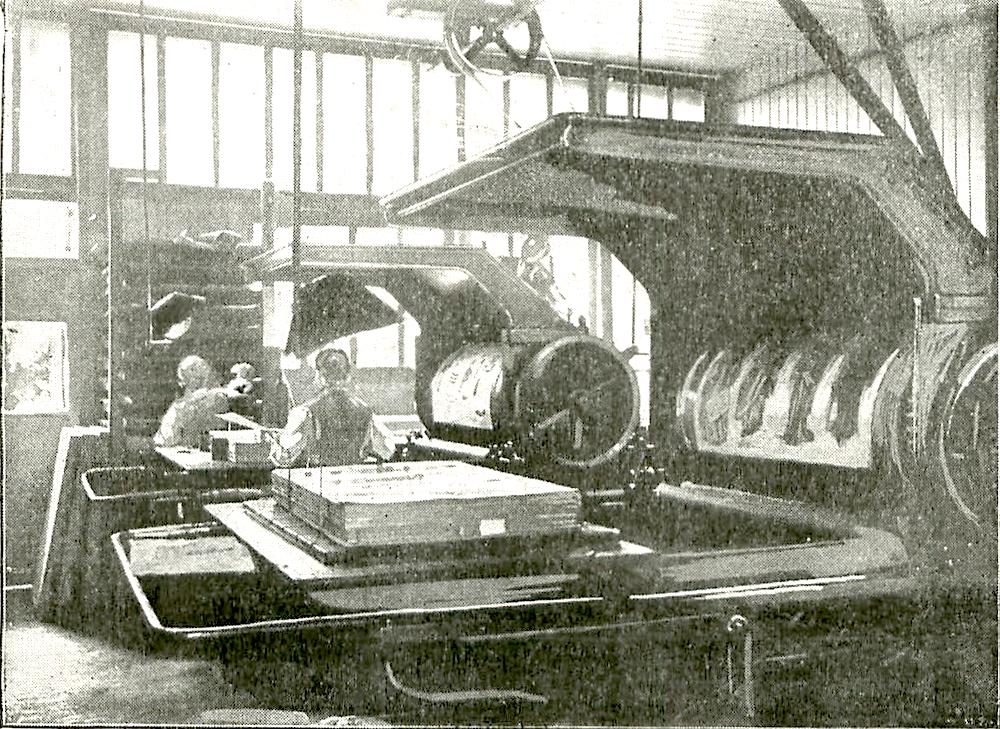

FIG. 15. — "Comic" machines at work.

Again, the favourite comic designs of Plymouth and Portsmouth are those which caricature in a genial way our gallant soldiers and sailors. The photograph we reproduce in Fig. 15 shows the "comic" machines at work. It is not a little amusing to watch the cylinders turning out these grotesque pictures with a rhythmical swing. The sheets of four are then cut up and sent to the dispatch department, where the designs are mixed, in order that retailers may get a complete assortment. Here the perennial comic policeman, who seems to be for ever receiving surreptitious grog or rabbit pie, has for his companions jovial soldiers and sailors, domestic servants of all grades, impossible tradesmen, more or less happy parents, and even several varieties of the so-called New Woman.

One of the very few of the valentine "commercials" left in London tells a woful tale of the dying trade. Every season a fresh batch of fancy dealers shake their heads at his approach, with the remark, "I don't think I'll go in for it this year." The valentine trade in the Metropolis is simply infinitesimal; the matter-of-fact Londoner prefers to send his lady-love a box of gloves on the "fourteenth," and we opine that the damsel herself prefers this useful valentine even to the chastely designed "sentimental" of to-day, though the latter be resplendent with aluminium frosting which costs a guinea a pound. [135/136]

It is a noteworthy fact that Ireland and Wales continue to take sentimental valentines in some quantities, the miners of Cardiff and the Rhondda Valley district paying as much as five shillings each for suitable designs; it goes without saying, of course, that appropriate valentines are designed for these places. Yet, notwithstanding support of this sort, there can be no doubt that the custom observed on the 14th of February will soon be numbered among the interesting memories of the past.

FIG. 16. — Valentine for the blind.

Perhaps the most extraordinary valentine we are enabled to reproduce is that shown in Fig. 16, a veritable valentine for the blind. It is to Lady Falkland that the idea is due; and this lady is one of the most charitable and industrious of the philanthropic "seeing workers" who devote themselves to the well¬being of their sightless brethren. Here is a translation of the playful verse in Braille type already given, which consists of raised dots systematically arranged:—

TO A FAULT-FINDER.

In speaking of a person's

faults

Pray don't forget your own;

Remember, those with homes of glass

Should seldom throw a stone.

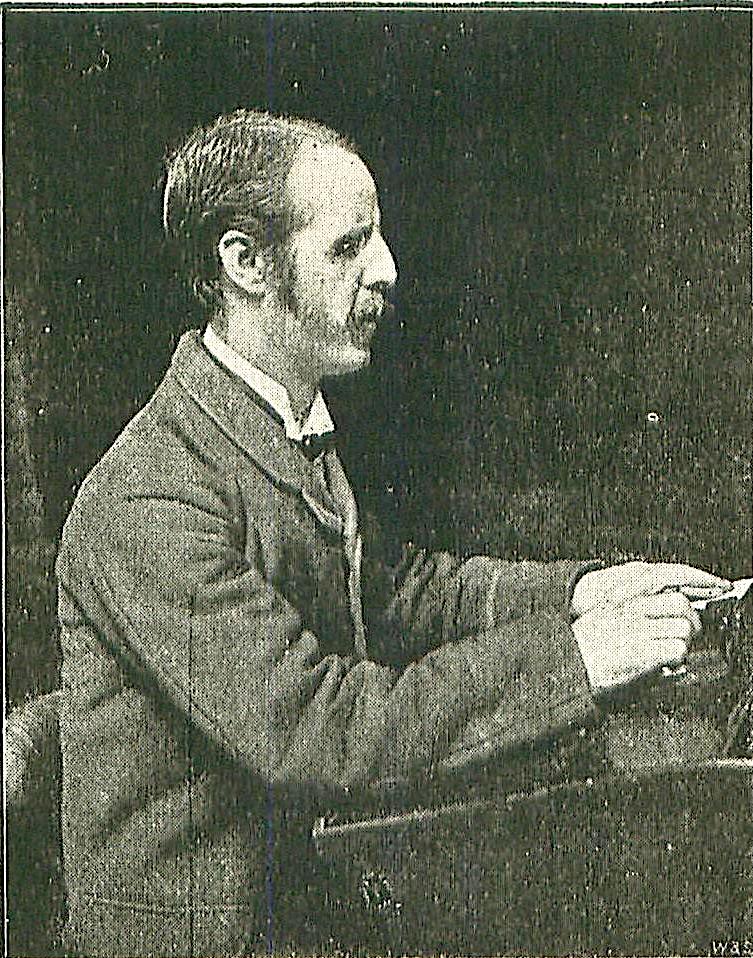

FIG. 17 — Blind operator making valentines for the blind.

Designs or figures of any kind are never put upon valentines or Christmas cards for the blind, simply because such designs and figures, being flat, would convey false impressions to these afflicted, but generally cheerful, people. Here is a photograph of the blind writer turning out valentines for the amusement of hundreds of his fellows all over the country (Fig. 17).

As a rule, a seeing person prepares; the first design; this enables the blind copyist to dispense with a seeing reader, who would otherwise be required to dictate the text. The photograph shows the copy beneath the left hand of the sightless, operator. With his right hand the blind man is punching the dots on the soft, thick paper, with a style resembling a gimlet, about 2 in. long. The paper is held firmly on the board by a transverse piece of brass, which also guides the lines and is punctured to allow of the dots being made through it. We are indebted for our reproductions of both valentine and photograph to Mr. G. R. Boyle, of the British and Foreign Blind Association.

Created 12 February 2023