Paintings of Indiamen by William John Huggins (1781-1845): Left: The Leguan. Courtesy of Grimsby Fishing Heritage Centre no. A111. Right: East Indiaman 'Herefordshire. 1815. Courtesy of the Science Museum No. 1834-307. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

As the Victorian age dawned so came the end of the East Indiamen; those armed merchant vessels which shuttled between England, India and China throughout the seenteenth and eighteenth centuries and into the early nineteenth. You often see them in prints of London docks, or Cape Town, Bombay, Madras and particularly of Calcutta, and Canton. Several artists specialised in them notably Robert Dodd and William John Huggins. They were attractive ships in black and white usually with one deck of about 30 cannons and thus often mistaken for Royal Navy frigates. They either flew the flag of the East India Company (similar to the US flag) or the Red Ensign.

Paintings of Indiamen by William John Huggins (1781-1845): Left: The East Indiaman “Saint Vincent” Saving the Crew of the East Indiaman “Ganges”, 29 May 1807. Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, London, no. BHC3622. Right: The East Indiaman 'Trafalgar'.. 1815. Courtesy of the Courtesy of National Maritime Museum, London, no. BHC3671. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Most of the Indiamen were built at yards on the Thames although some were constructed of teak at Bombay. Each would make one return voyage to the India every year. Their log-books are still available at the British Library, meticulously kept in copper-plate script; detailing crew, passengers, cargo and every detail of each voyage. The average later Indiaman would last for 6 return voyages before the toll of the heavy seas and fierce winds and shipworm took their toll on hull, masts and rigging. The occasional Indiaman would last longer. The Scaleby Castle managed 14 return trips.

One Family’s Voyages aboard East Indiamen

The most famous descriptions of voyages aboard East Indiaman are to be found in the bawdy diaries of William Hickey. They are remarkable for the vast amounts of food and alcohol consumed by the passengers and for the general discomfort of being cooped up with 250 others on a small 300 ton ship for 3 months.

I shall follow the experiences of one family, the Richardsons of Langholm on their several Indiaman voyages. Eliza made 4 voyages. She had travelled out to Madras in a Danish Indiaman, a reminder that the Dutch, Danes, Portuguese and French all had small colonies in India. Gilbert Richardson, her husband, was an Indiaman Captain himself. Their son, Oliver, was an officer in East Indiamen before becoming one of the first settlers in South Australia. He would make 9 return voyages out east. From the 11 voyages for which logbooks still exist in the British Library some patterns emerge.

The loading in the River Thames always took a couple of months beginning in November with the Captain arriving shortly before the vessel set sail in January. Then there was always the wait, often a long wait, for the right winds off the Downs which took the ship into mid-Atlantic and almost to the coast of Brazil before the turn south-east for the Cape of Good Hope. It is interesting that some of the most dangerous moments of the whole voyage were off the south coast of England where the prevailing winds threatened to blow an Indiaman onto the rocks of the Dorset or Devon coasts.

Sometimes East Indiamen stopped at Cape Town to replenish food and water or to disembark or collect troops. On others they would continue directly to Bombay, Madras or Calcutta. On the return trip the ships occasionally stopped at Cape Town but more often went directly to St Helena for supplies before reaching the south-west coast of England and eventually the River Thames at Gravesend.

Navigation was a constant concern. There would always be three chronometers aboard and their readings would be compared each day. In 1823 Oliver qualified in the ‘lunar method’ of finding Longitude at sea; and at “working the time for corrections of chronometers”; and “in measuring angular distances, taking altitudes with an artificial horizon”.

Mostly the Indiamen travelled in convoy of 5 or 6 ships. During wartime (invariably with the French) a Royal Navy warship would accompany them and the Navy captain would be in command. At any moment the Royal Navy could conscript members of an Indiaman’s crew. This was the source of constant resentment. On two of Eliza’s trips home from Madras there were brushes with French warships. In 1806 aboard the Charlton she watched as their escort engaged in a battle with a French warship.

The cargoes were hugely valuable. On Eliza’s first trip from Calcutta to London aboard the Eliza Ann they carried indigo, sugar, long pepper, gum copal (a binding agent used for varnishes, paints, and adhesives), shellac (a wood stain and varnish), cotton cloth, nox vomica (a nut which produces strychnine), asafoetida (for cooking and medical uses) cassia (a bark similar to cinnamon) , elephant’s tooth (ivory), saffron, silk, cayenne pepper, curry and saltpetre (for gunpowder). With England at war with France the saltpetre was a vital strategic requirement. But in addition to his official cargo Gilbert also carried some private goods. An Indiaman captain would expect to become very wealthy after just 3 or 4 trips home.

Fever was a constant worry and often ran rife amongst the British troops on board. Sometimes they had to run up a quarantine flag and not go ashore until a set period had elapsed. On a voyage in 1801 the troops on board belonging to the 12th and 75th Regiment developed fever. Soon 204 of the troops were ill and their commander insisted on a stop at Cape Town for recuperation. The Captain suspected malingering but was obliged to spend a month in South Africa before continuing to Madras

Oliver made numerous return voyages to China aboard the Earl of Balcarras. In Calcutta they would take on a load of cotton for China. Sometimes they sailed via Prince of Wales Island (modern Penang) and through the Malacca Straits. On others they went through the Sunda Straits (between Java and Sumatra) catching sight of the huge volcano of Karakatoa (which famously exploded in 1883). From Macao they went up the Canton river [now known as the Pearl river] to Whampoa, then an anchorage 15 miles from Canton, where they delivered 143 chests of treasure to three other Indiamen before loading tea and setting off on the return journey. Sixteen months was pretty much standard for an Indiaman’s voyage to China and back.

Pay was good. For his second voyage Oliver earned £28.4s.2d as 5th Mate. By comparison the Captain received £142.17s.6d and the average seaman earned £22.12s.5d. There was very little on which to spend money during 16 months at sea except for the short stops at Bombay, Penang, St Helena and the longer sojourn at Whampoa. The log of Oliver’s 1828 trip to China contains more human interest detail than most. The log mentions Divine Service on Sundays. It provides sick lists. There were usually 10 men ill at any one time. In June a seaman was sentenced to two dozen lashes and two weeks later the same sailor was placed in irons for indolence and disobedience. At anchor at Singapore, after unloading, they caulked the decks before setting off for China in early August. At Whampoa they scrubbed the hammocks, washed the gun decks and painted parts of the ship. They delivered private trade to Whampoa and unloaded “the Company’s bales [of cotton] and iron” and took on board “the Company’s teas”. In mid December they set sail for England. 3 dozen lashes were awarded to a seaman for drunkenness and insolence. At Singapore on 3rd January, the Canning burnt a blue light [a nautical means of seeing in the dark, often when there was concern about nearby reefs or other hazards]. On 8th February the water was down to 180 gallons but they took on supplies at the Cape of Good Hope before arriving at Gravesend on the 9th.

In 1834 the East India Company’s Maritime Service lost its monopoly on trading with India and the service itself was disbanded. The Earl of Balcarras was sold to Thomas Shuter on 17th February 1834 for £10,700. Oliver became eligible for a pension and compensation payment and was awarded a Third Mate’s annual pension of £80 per annum and a gratuity of £750 payable from the 23rd April 1834. That was enough to start a new liefe.

Three factors that spelt the end of the East Indiamen

1. The first was the invention of steam power. In 1825 the steam powered SS Enterprise made her first trip to Bombay. It was not a great success but the logic of using steam power was compelling.

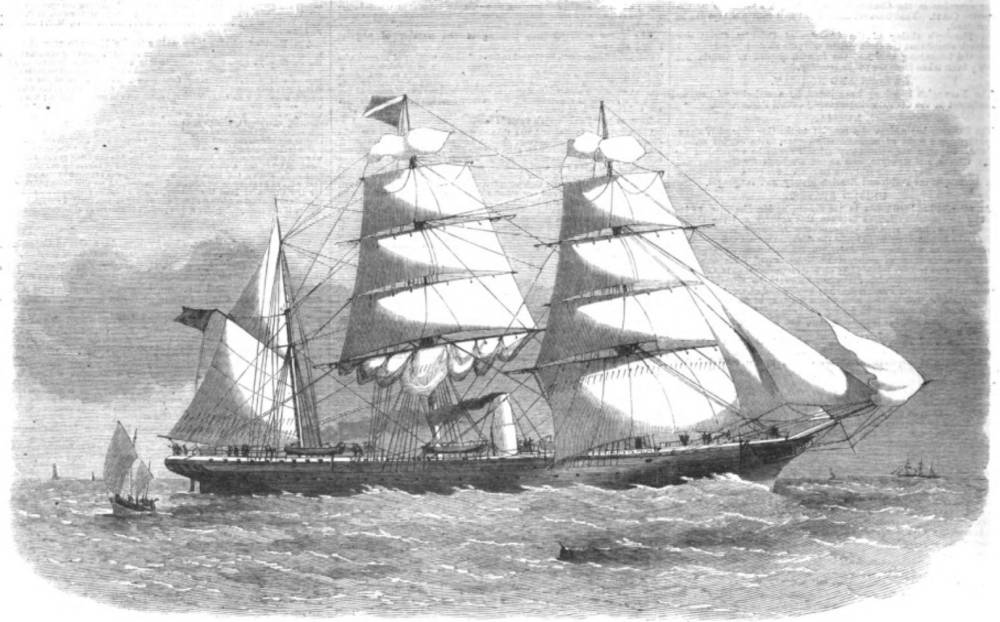

The Auxiliary Screw-Steamer “Erl King,” Built at Glasgow for the Australian and China Trade. The Illustrated London News (1866).

2. The second was the adoption of the overland route to India. By 1835 the trip via Trieste, Alexandria, Cairo and Suez was becoming the preferred journey, replacing the discomfort and danger of the voyage around the Cape of Good Hope.

3. And the third was the ending of the East India Company’s monopoly on transportation to India in 1834. New commercial companies such as the Peninsular and Orient Lines (P&O) and British India Lines started to operate the routes.

Related Material

Bibliography

Bowen, H.V. et al. Monsoon Traders. London: Scala, 2011.

Cuming, Ed. A compendium of incidents incurred by the major Ships of the East India Company. Nautical Archaeology Society. 2016. Web. 10 August 2020.

“[H.C.S.] Alexander.” Deeper Dorset. Web. 10 August 2020.

“Shipwrecks and the East India Company’s Immaterial Material Culture.” Warwick University. 2012.

Sutton, Jean. Lords of the East. London; Conway, 1981.

Created 12 August 2020