[Click on thumbnails for larger images. You may use these and the following images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Windows in the Chancel, South Aisle West, and Cloisters

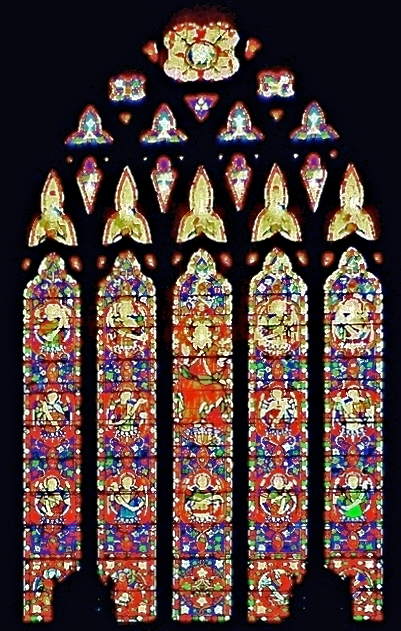

Left to right: (a) Pugin's beautiful and intricate east window, the tracery lights dating from 1848, and the main lights from 1849: Christ in the centre surrounded by angels (including five in the large tracery lights just above the main ones), with Matthew, Mark, Luke and John in their symbolic forms at the base. (b) Closer view of some of the angels in the main lights, all unique, picked out against red backgrounds and bearing scrolls. Note the unifying vine pattern. (c) In the west wall of the south aisle, Pugin's window of King Ethelbert and his French Queen, Bertha, who both became saints: Ethelbert welcomed Augustine to England, and was subsequently baptised. Note the white horse of Kent in Pugin's topmost tracery light. (d) One of the beautiful cloister-windows, some by Pugin, some by Powell taking his cue from Pugin, all illustrating Pugin's love of stylised natural forms.

The stained glass at St Augustine's makes a fascinating study, mainly because of its aesthetic appeal, but also because of what it shows about Pugin's approach to this medium, and about his religion. According to his assistant John Hardman Powell, who designed many of the windows after his death, the two were closely related: "Pugin's ideal of Stained Glass was a high one," wrote Powell, adding that he was "not content with skilful drawing or even right principles, but aiming to rival the religious spirit and fervour of the Middle Ages" (22). The east window of the chantry is a good example here. So minutely worked that it is hardly possible to do it justice, it has a kaleidoscopic effect, and meets the eye almost like an epiphany. In the upper part of the central main light sits Jesus, with a halo in shades of green and ochre, holding an orb topped by a white cross in one hand. He wears an ochre-coloured robe with darker folds, edged with a white border. Below the outer robe, visible above the waist and again in the lower right-hand corner, is a red gown; there is also a sash in different shades of green. The composition and palette are both beautifully nuanced. As can be seen in the close-up, every angel is differently garbed and holds his scroll in a different way. Compare this with another east window by Pugin in St Paul's, Brighton, equally densely detailed and hard to capture in a photograph.

The window depicting Ethelbert and Bertha, in the south aisle, was also completely installed in Pugin's lifetime. In fact, like the font at St Augustine's, it was exhibited in the Medieval Court at the Great Exhibition, where it was picked out for praise by the Illustrated London News, as having "all the advantages of producing a rich effect, without impeding the sufficiency of light from entering the edifice" (qtd. in Fleet and Blaker 18). It looks quite simple here, but on closer inspection the background detail is amazing, with yellow-gabled canopies above the figures, little green windows rising behind them, and a white roof complete with parapets. Even the cloister windows have more in them than first appears, with fleur-de-lys and other patterns in the diamond panes. These latter windows foreshadow the widespread use of floral motifs and geometric patterns in domestic stained glass during the later Victorian period.

St Augustine's Window in the Pugin Chantry South

Left to right: (a) The whole window, with tracery lights by Pugin dating from 1849. The central quatrefoil of these small lights shows St Louis of France in white robes with a green stole. Below are Powell's main lights of 1861, showing episodes from the story of St Augustine's mission to England. This is over Pugin's tomb chest in the family chapel here. (b) The first of the lower two panels, shown here, depicts (l. to r.) Gregory as a monk in the slave-market in Rome, seeing the fair "Angles" from England as "Angels"; Gregory as Pope (seated) sending Augustine (kneeling) on his mission to England; St Augstine landing near Ramsgate — note the ship's sail in the background; and St Augustine being met by King Ethelbert. In the bottom panel are Pugin and his three wives. (c) Pugin with his church, complete with the spire that was never erected, receiving St Augustine's blessing. (d) Pugin's first wife Anne, supported by her name-saint.

It is sad that the window which began with a tribute to St Louis in the tracery should have served as Pugin's own memorial. Louis was the French King responsible for La Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with its awe-inspiring stained-glass — two fragments of which Pugin had acquired when the chapel was being used for storage after the French Revolution. As it happened, Pugin really hated the way St Louis had turned out in the top quatrefoil: "the white figure from below looks like a mass of dirty white," he grumbled (qtd. in Shepherd 285), blaming Powell for botching it in his absence. But perhaps the rest of the window would have pleased him. Its focus on St Augustine is doubly appropriate, since he was Pugin's own name-saint, and first landed in England on the local shore, as narrated in the window itself. One poignant detail is the depiction of St Augustine's church in the left-hand corner, with the spire originally intended for it. Pugin made the church over to the diocese of Southwark in 1846, and although his sons Edward Welby and Peter Paul Pugin continued to work on it after his death, funds never stretched to that important addition. Pugin's Catholic Cathedral in Southwark itself, St George's, suffered the same fate.

A Sample of Other Windows with Tracery Lights by Pugin and Main Lights by Powell

Left to right: (a) Still in the Pugin Chantry, St Laurence of Rome and St Stephen, with tracery lights by Pugin in 1849, but main lights thought to be later. As early deacons, both saints carry bibles, St Laurence additionally bearing a martyr's palm, and St Stephen a censer. (b) Detail of Pugin and Hardman's window in the Lady Chapel East, showing St Agnes on the left with her martyr's palm, and St Margaret of Antioch with the dragon which swallowed her, but from which she miraculously emerged; the main lights here are by Powell, dating from 1861. (c) In the south wall of the south aisle, near the font, St Bede, St Winifred and St Cuthbert, with the latter holding St Oswald's head (which was found to have been buried with him). All these saints were closely associated with the Benedictine order, for which Edward Pugin built St Augustine's Abbey opposite the church. Again, Powell designed the main lights in 1861. (d) In the north wall of the nave, three Benedictine nuns who became saints: St Gertrude, St Mechtilde, and St Mildred. As elsewhere, the tracery lights were by Pugin, while the main lights were added by Powell, this time in 1868; the lower middle tracery light may have been replaced then as well.

Puginesque features can be found in the main lights of St. Stephen and St Laurence (the red background, the peep of green in the lining of the robes), but these may well have been by Powell, who after all was Pugin's protégé. Pugin was known, too, to dislike "independence of spirit and drawing style" in those who worked with him (see Hill 364); it was some time before Powell established a style of his own. The main lights in the Lady Chapel's east window were definitely added later by Powell, yet here again the stylised lilies, seen rising from white, red-banded pots along the lower edge, have been seen as "particularly Puginesque in their inspiration and design" (Fleet and Blaker 6). Less Puginesque, perhaps, is the vivid depiction at the base of the central panel, of God appearing amid the licking flames of the burning bush (from Exodus 3).

As for Bede and the other northern saints, these were partly chosen because the earliest post-Reformation Benedictines in this area were named after them (see Fleet and Blaker 15). A local reference appears in the other window shown here, too: the last of the nuns featured in the nave window, St Mildred, was the abbess of a local abbey on the Isle of Thanet. She is seen here with her tame deer. The nuns' robes are a rich deep purple rather than grey, as they appear here. Notice Pugin's rather jauntily-posed angels facing each other in the larger tracery lights, flaunting their scrolls.

Windows by John Hardman Powell in the Digby Chantry

Left to right: (a) St John and St Thomas, in the south wall, dated about 1859. Note Powell's tracery windows with bold fleur-de-lys and vine-leaf patterns. (b) Close-up of St John and St Thomas, the former holding the legendary poisoned chalice, and the latter a bible and staff. (c) The Virgin Mary and St Kenelm, again all (including the tracery lights) by Powell in about 1859. (d) Close-up of the young St Kenelm — in the Nonne Preestes Tale, Chaucer recounts how he was warned of his death in a dream.

This chapel was designed by E. W. Pugin for the Catholic convert and religious writer Kenelm Digby, as the Digby family's last resting-place. Both tracery and main lights were designed by Powell in about 1859, and are similar in style to Pugin's. However, the large west window of the nave (not illustrated here), dating from 1875 and depicting scenes from the life of St Benedict, shows how he gradually moved away from Pugin, and adopted a "more literal or pictorial approach and sinuous, almost fluttery, line" (Fleet and Blaker 21). The development would surely not have met with Pugin's approval: "no line, not a sharp bit about it," he had inveighed, when criticising Powell's work on St Louis (qtd. in Shepherd 285). Nor was the Hardman firm's later work as popular with other architects: "Hardman's glass is getting worse & worse," complained G. F. Bodley in 1867. "Pugin's influence started them well, but it is a great risk now what you get — the windows I have seen lately are terribly bad in colour & drawing" (qtd. in Shepherd 190). As is clear from this alone, Pugin had set standards which later designers in this area had to struggle to emulate.

Related Material

- St Augustine's Church (views and other features)

References

Fleet, Robin, and Catriona Blaker. The Stained Glass of St Augustine's Church, Ramsgate. Ramsgate: Potmetal Press, 2010.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Making of Romantic Britain. London: Penguin, 2008.

Powell, John Hardman. Pugin in His Home: Two Memoirs by John Hardman Powell. Ed. Alexandra Wedgwood. New enlarged edition. Ramsgate: The Pugin Society, 2006.

Shepherd, Stanley A. The Stained Glass of A. W. N. Pugin. Reading: Spire Books, 2009 (see especially the Gazetteer, pp. 281-6).

Last modified 12 October 2010