This review of an exhibition held at the Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, from 25 January to 17 April 2008, was first published in the Art Tribune of 15 April 2008. The original can be seen here. It has been adapted and reformatted for our site with Professor Capet's kind permission. Many thanks to Leighton House Museum for allowing us to reproduce the images from it. Click on them all for more information. — Jacqueline Banerjee.

rnest Gombrich once wrote about “the whirligig of taste” and nowhere can this better apply than in the case of Victorian academic painting – and even more so in the case of its leading figure, Frederic, 1st Baron Leighton (1830–1896), whose impressive list of honours shows the immense prestige which he enjoyed both in Britain and abroad: “No other artist of the Victorian age has done better work, has been better known in the world, or has filled a larger space in the eyes of the public,” said his obituarist in The Times. If one accepts that the number of books about a given person reflects the interest in him, a search in the catalogue of the British Library makes it clear that a pre-1914 peak was followed by a long trough, with interest apparently slowly picking up again. During the recent "Millais, Hunt and Modern Life" Symposium at Tate Britain (29-30 November 2007) his name repeatedly recurred, and in fact a slide of his extremely famous Flaming June of c.1895 was shown by one of the speakers.

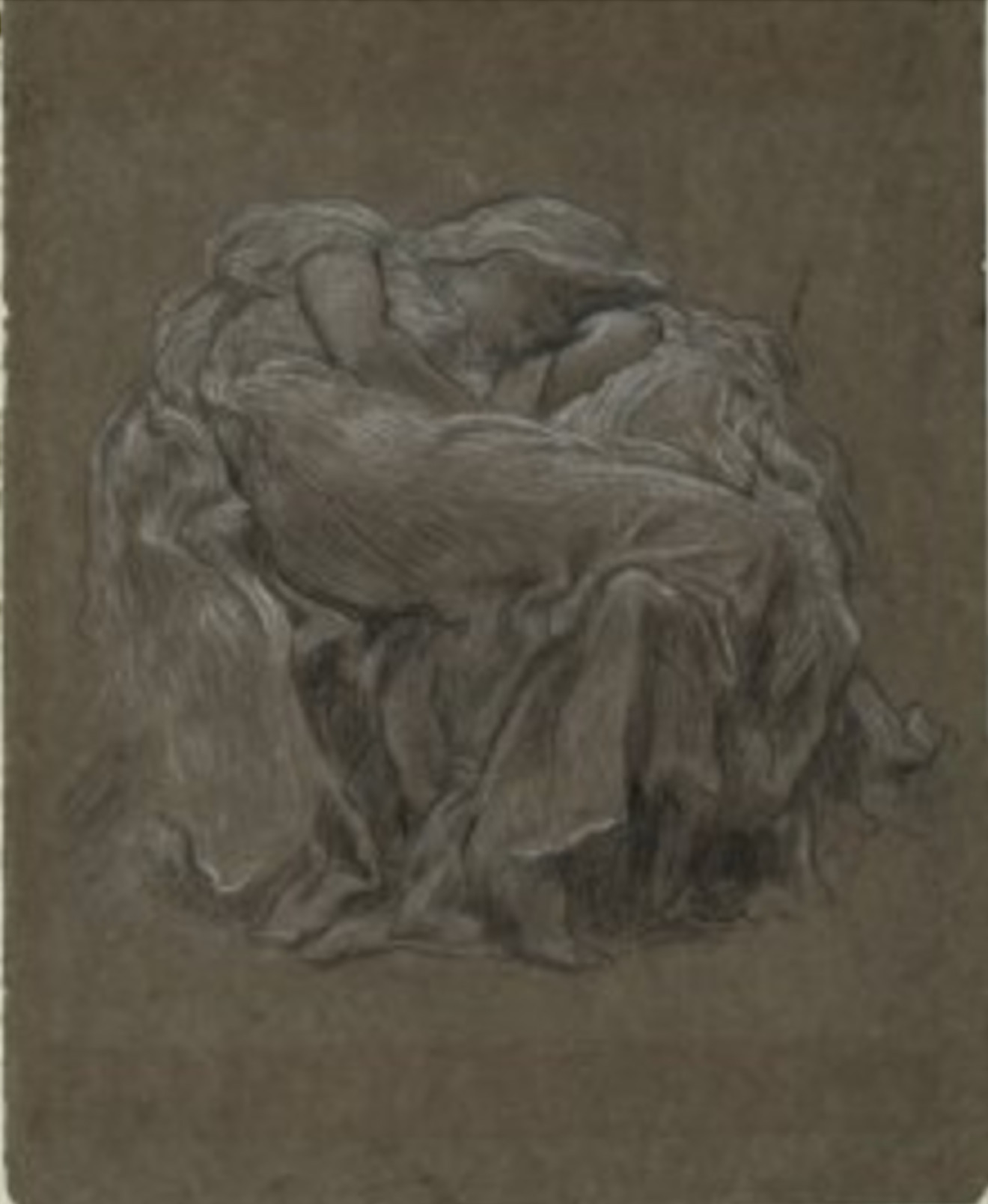

Study for “Flaming June”: Female Figure, c. 1894.

Professor Pamela Robertson, the Senior Curator of the Hunterian Art Gallery (which is part of the University of Glasgow), also gave a lunchtime talk on “Leighton and Flaming June” in March, in connection with the current exhibition – which shows again how much Leighton’s name is associated with that picture among the public. Philippa Martin, Project Manager of the Leighton Drawings Project, calls it “a symbol of High Victorian Art” in the Catalogue (p.100). Naturally, even though the exhibition is primarily devoted to drawings, as its title clearly indicates, a reference to Flaming June was de rigueur, and there are two Studies for “Flaming June”: Female Figure on display, both black and white chalk on brown paper, c.1894. Now, two approaches are possible for the visitor: either one considers each drawing per se, forgetting the “finished” painting for which it served as preparatory work (most of the fifty-five drawings exhibited, all taken from the Leighton Drawings Collection, were preliminary studies of one category or other), or one enters into a comparative study, much as editors of written works analyse the various phases of the text in the manuscripts left by great authors. The latter approach, which usually teaches us a lot about the intellectual process of a given creator by revealing his hesitations and alternative strategies, is probably best left to the professional historian of art. The general educated public will enjoy the visit far more intensely if treating each drawing as “finished” work – which indeed it is in the majority of cases. But this is not always possible when the “final” painting is so well known.

The curators have divided the exhibition into six sections, largely based on chronological considerations. One starts with “A Continental Beginning, 1849-1858”, and with the dilemma: how best to approach the three superb Studies for “Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna”? It is well known that the painting was immediately bought by Queen Victoria when it was exhibited in 1855 — it is still in the Royal Collection. How then can one forget the celebrated “final product” when looking at the three studies which the Senior Curator at Leighton House, Daniel Robbins, tells us, “represent one of the pinnacles in his entire output as a draughtsman” (Catalogue, p. 29)? One way of evading the difficulty is to concentrate on the magnificent rendering of an old cypress tree, Study of a Cypress Tree, Florence (1854) – it was used later (in one case almost forty years later), but for unfamiliar works.

Likewise, in the next section, “Six Weeks in Capri, 1859”, it is a tree which unquestionably stands out: Study of a Lemon Tree, Capri (1854). This fairly large sheet (53 x 40 cm) constitutes “the most elaborate drawing that he ever made”, as Christopher Newall reminds us, adding that “it has been uniquely famous and intensely admired since the time it was made” (Catalogue, 51 — Christopher Newall was one of the organisers of the Leighton Centenary Exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1996). And one can understand why – the charm which the original exudes can never be conveyed by reproductions (especially the fine little snails, which benefit from special treatment).

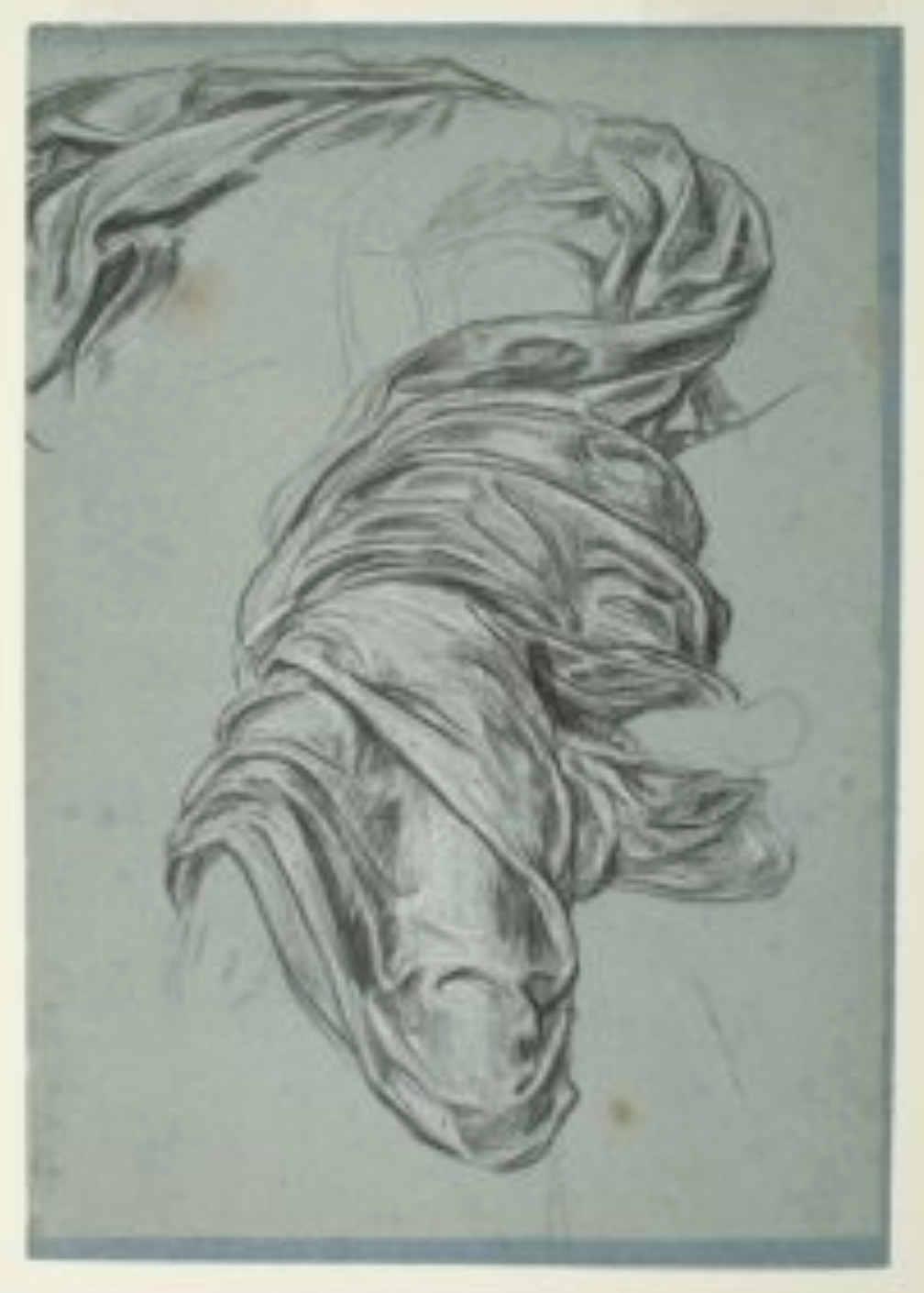

Study for “Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis”: Drapery for Death (c.1870).

In “Consolidation and Advance, 1859-1876,” Reena Suleman, Curator of Collections and Research for the Leighton House Museum, seems to suggest that the most important work, “as an early example of Leighton’s large-scale study of drapery” (Catalogue, p.58), is the Study for “Hercules Wrestling with Death for the Body of Alcestis”: Drapery for Death (c.1870). No doubt this may be so for the specialists who want to document the evolution of Leighton’s technique – but one may bet that in that section the amateurs will yield instead to the juvenile charm of the unknown sitter in Study for a Female Head (c.1870).

Head of Dorothy Dene, 1881.

There will be little disagreement that in the section on “Working at Home in the Studio, 1877”, the most important series is that of the four Studies for “Elijah in the Wilderness”: Elijah (c.1877). The well-known painting, now at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, was first exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878 – and once again it is difficult to forget it when looking at the “preparatory” drawings.

The next section is entitled “Presidential Eminence, 1878-1893” because of Leighton’s election as President of the Royal Academy in 1878. Two complementary qualities in Leighton’s art are in evidence in this section: his mastery of drapery and his mastery of juvenile female portraiture. Once again, one may like or dislike the “academic” paintings which constituted the “end products”: (The Dance, 1883, and Music, 1885, both at Leighton House; Cymon and Iphigenia, 1884; Sybil, 1889; and And the Sea gave up the Dead which were in it, 1892), but few visitors will remain insensitive before Study for “The Dance”: Drapery for Girl (c.1882), Study for “Cymon and Iphigenia”: Drapery for Iphigenia (c.1883), or Study for “Sybil”: Drapery for Female Figure (c.1889). The complex blending of the muscular shapes of the male breast, neck and throat in Study for “And the Sea gave up the Dead which were in it”: Male Figure (c.1881) naturally shows Leighton’s proficiency in anatomy – but on top of that proficiency the beautiful drawings of his favourite model, Portrait of Dorothy Dene (c.1880) and Head of Dorothy Dene (1881 ) have an aesthetic warmth which cannot fail to strike the visitor.

The last section, “The Final Years, 1894-1896”, comprises the two Studies for “Flaming June” already mentioned, but as a “swan song” the five Studies for “Clytie” (c.1891-1895) are unparalleled, not only for their intrinsic quality – notably Study for “Clytie”: Head (c.1895) and Study for “Clytie”: Hair (also c.1895) – but also for what they probably tell us about Leighton’s frame of mind on the eve of his death, whose imminent coming he could not ignore as a result of his increasingly frequent attacks of angina. If Flaubert famously said of his heroine “Madame Bovary, c’est moi,” it is perfectly plausible that Leighton was telling us (and perhaps himself) “Clytia, it’s me”. In the excellent Catalogue notes, Philippa Martin reminds us of the narrative: Clytia is a character in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. “Having been scorned by her former love, Apollo, god of the sun, she gazed at the sun in grief for nine days, without food or drink. Eventually the gods took pity on her and transformed her into a flower” (Catalogue, p.106). The drawings and the painting naturally depict the period of grief, when she did not know she would be saved. That Leighton felt a particular empathy with this desperate mortal creature at such a tragic juncture in his own life is perfectly conceivable. The attitude of absolute despair and last-minute imploration in Clytia must have reminded many God-fearing Presbyterian and Roman Catholic Glaswegians of the Aramaic words attributed by the Evangelist to Jesus before he breathed his last: “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani" ("My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?" Matthew 27:45-46). Whatever Leighton’s real beliefs, he had of course been brought up in the Christian tradition, and these harrowing words may – or must – have been somewhere at the back of his mind when he drew Clytia in such a powerful pose, which in a way sums up the human condition.

Leaving the Exhibition, a dual set of reflections come to mind. The first has already been alluded to: Gombrich’s “whirligig of taste” fully applies to all these magnificent drawings. The 21st-century amateur and connoisseur wonders how and why they were neglected for so long. In contrast, it is arguable that the “finished” paintings are still in Purgatory – at least outside the world of art historians and specialists. And it is equally arguable that the “whirligig” will take a far longer time to turn again in their favour: the drawings immediately “speak” to us – not so the paintings, at least not yet.

The second has to do with the acceleration of the evolution in artistic tastes and movements in that fin-de-siècle. Leighton died in 1896. The Hunterian Art Gallery has a superb section on the Glaswegian artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), in The Mackintosh House, notably with objects designed for the “Rose Boudoir” exhibited at Turin in 1902. Incredibly (but then one can see tangible proof of this at the Hunterian), only six years separate Clytie from the “Rose Boudoir” objects. To the “whirligig of taste” in the longue durée, we may add, it seems, the whirlpool of British creative inspiration in the short period between Leighton’s death and the end of the Edwardian period. Useful comparisons may also be made with the Camden Town Group in London.

Considering that the Hunterian Art Gallery also boasts “the world’s largest display of Whistler’s art”, it is clear that a visit will be more than rewarding for anybody interested in late 19th-century and early 20th-century art.

Link to related material

- [Offsite] Drawings by Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-1896) (Borough of Kensington and Chelsea)

Bibliography

Catalogue: Harrison, Miranda, ed. A Victorian Master: Drawings by Frederic, Lord Leighton. London : Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, 2006. ISBN: 0902242245 / 9780902242241. 132 pp. A4 Paperback. £14.95.

Gombrich, Ernest. “The Whirligig of Taste.” Reflections on the History of Art: Views and Reviews. Edited by Richard Woodfield. Oxford: Phaidon, 1987. 160-167.

Obituary. The Times. Monday 27 January 1896. Issue 3497, p.8.

Last modified 15 January 2006