dvertising was one of the motors of Victorian capitalism. Facilitating the process of winning markets, it reached out to large, mainly middle-class audiences, and helped to consolidate the United Kingdom’s economic transition from a society based on localized work to the development of industrial production. Advertising took many forms: leaflets, bill-boards and posters, handbills, flyers and trade-cards were ubiquitous; the walls of Victorian cities were plastered with an ever-changing, fluttering display; advertisements appeared on packaging; and commercial papers of all sorts dominated the home and work-place. These documents reflected the Victorian emphasis on decoding visual signs and became an integral part of the culture, reappearing in realist paintings of the street and in imaginative literature, a theme explored by Sara Thornton in Advertising, Subjectivity and the Nineteenth Century Novel (2009).

Especially important are the advertisements appearing in the paratextual frameworks that enclose Victorian writers’ works as they appeared in magazines, newspapers, serialized instalments of novels, and books issued in trade bindings. This material is important because it extends its pitch into the home, a process prefiguring the modern dissemination of sales material on television and on the internet. Though the urban environment was dominated by changing displays which set out to catch the (potential) consumer’s attention as he or she passed it on the street, the experience of the flâneur, advertisements viewed in a domestic setting must surely have had a greater impact, connecting a product with the context in which it might be used by reminding the buyer of what might be needed for the kitchen, parlour, bedroom, or nursery. Linking the domains of work and family, well-being, necessity, and leisure, this paratextual feature is an intimate, telling sign of Victorian values and attitudes.

The Language and Idiom of Advertisements Appearing in Magazines and Books

ournals employed advertising on a large and often intrusive scale. Positioned in the endpapers, front and rear, they are sometimes carried over onto the rear covers. This convention is embodied by The Quiver in the 1870s and Once a Week and the Cornhill in the sixties.

Commodities of all sorts were promoted in these documents, selling everything from steel-nibbed pens to whiskey, ladies’ riding trousers, beer, spirits, starch, extract of elderberries, cocoa, sewing machines, insurance, toys for baby, (spurious) medicines, cigars, umbrellas and everything else that might be used in a domestic setting or by members of the family: the list is as endless as the Victorian consumer might demand. Indeed, the teeming productivity of the Victorian economy is enshrined in these pages, symbolizing the absolute emphasis on consumerism for those with the financial means to partake in the nexus of trade; as Thomas Richards remarks, ‘nineteenth century advertising consisted almost entirely of the bourgeoisie talking to itself’ (7), of producers and consumers engaged in the dynamic exchange of an emergent capitalism.

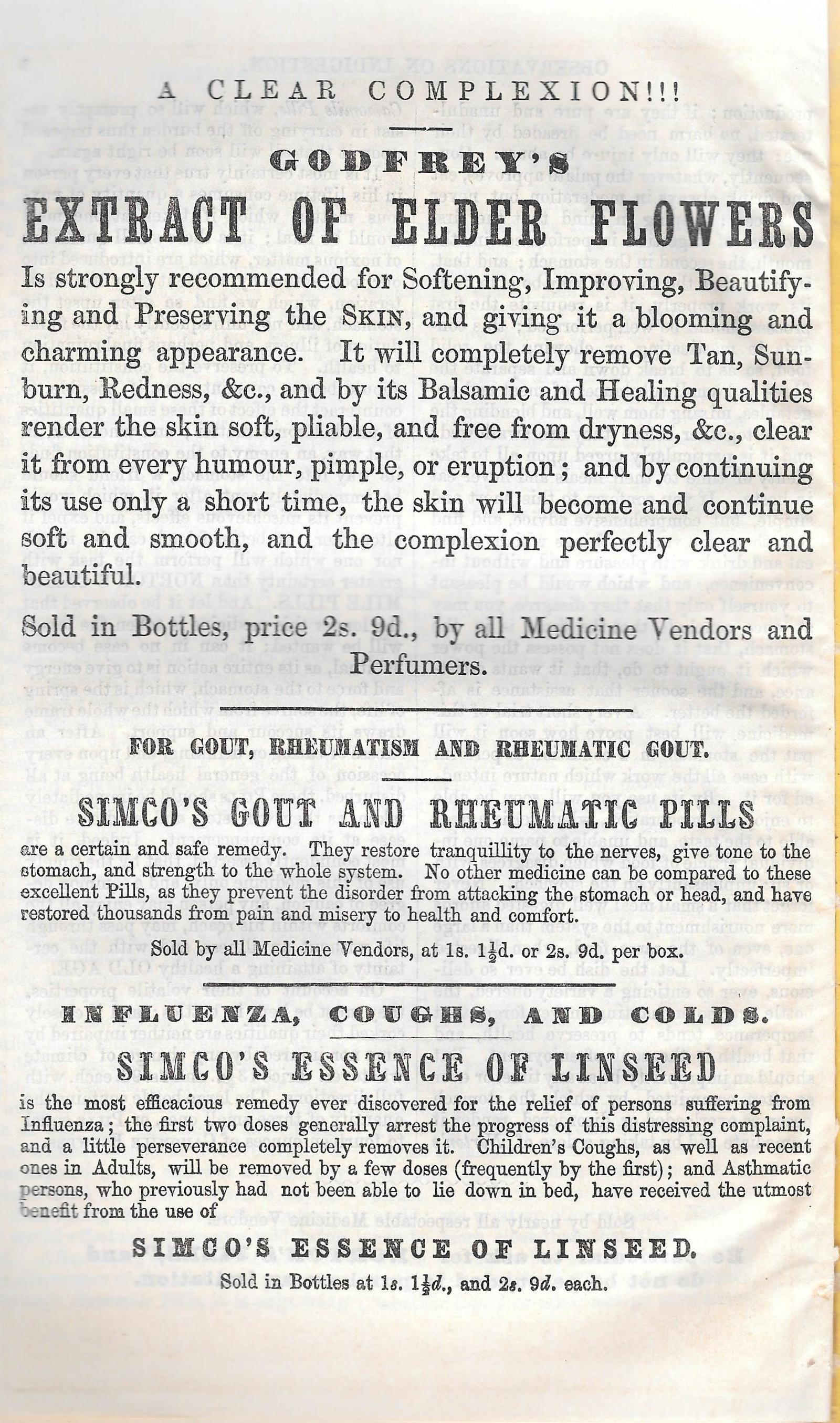

The selling technique of these advertisements was initially fairly undeveloped, and seems naïve to modern eyes. Continuing the traditions of eighteenth century merchandising, most early and mid-Victorian commercials are text-based; lacking illustrations, they are verbose and over-written, and it was not until the period after 1875 that visual material came to the fore. Mid-Victorian advertising does not present the slogans and tag-lines found in modern commercials, but it does deploy persuasive techniques such as hyperbole and unsubstantiated claims. ‘Godfrey’s Extract of Elder Flowers’ for ladies, from The Cornhill, manipulates these tropes. We are told that application of the lotion will make the complexion ‘perfectly clear and beautiful’, eliminating every ‘pimple, or eruption’ while giving the skin a ‘blooming and charming appearance’. None of this has any basis in science, but the product is endorsed (‘strongly recommended’) by an unidentified authority. Simco’s gout and rheumatic pills, advertised on the same page, are likewise projected as efficacious medicine, this time deploying comparatives and superlatives; ‘Excellent’ pills, and with ‘no other medicine’ to compare with them, they are said to have ‘restored thousands from pain and misery to health and comfort’. Such ‘quackery’, as Thomas Carlyle dubbed it in his excoriation of advertising in Past and Present (1843), is misleading, and always calculatedly economical with the truth. However, this approach, deploying the language of exaggeration and false claims, is entirely typical of mid-Victorian advertising operating in this context.

Another technique, and one entirely at odds with modern approaches, is the emphasis on prolixity. Sometimes advertisements run for pages of densely-packed columns on sheets added to periodicals’ endpapers. In an issue of The Quiver, for example, ‘Norton’s Camomile Pills’ are promoted in a four-page booklet containing about 500 words in which its power as a cure-all is elaborately explained. Put simply, most Victorian advertisers sought to promote their wares not through the agency of slogans, but by trying to persuade the consumer to buy by explaining the qualities of their product at great length, and sometimes in microscopic detail. This laborious over-writing seems to have been equated in the public mind with authority: the more that was written, and the greater the elaboration, the greater the likelihood of the product’s and seller’s integrity.

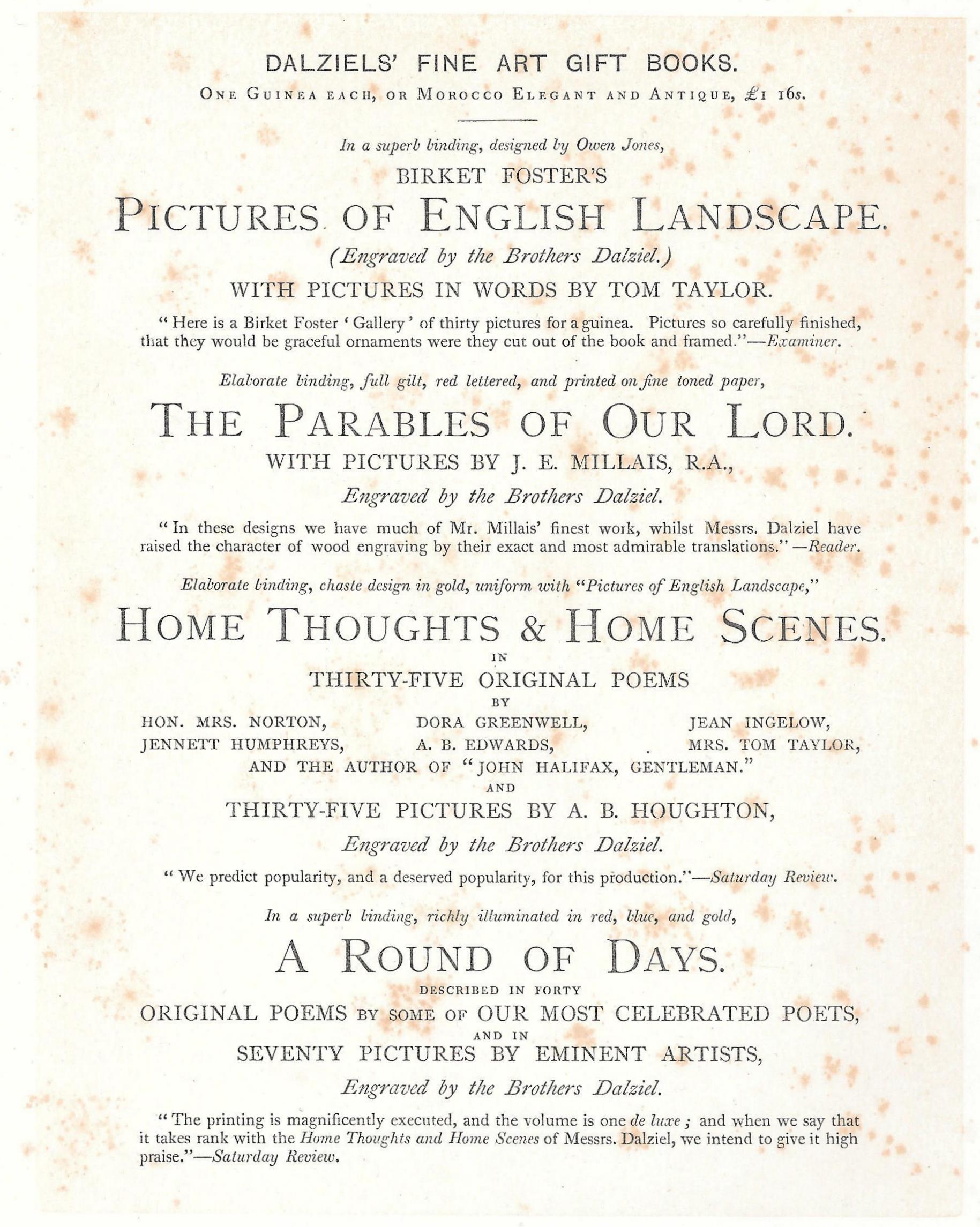

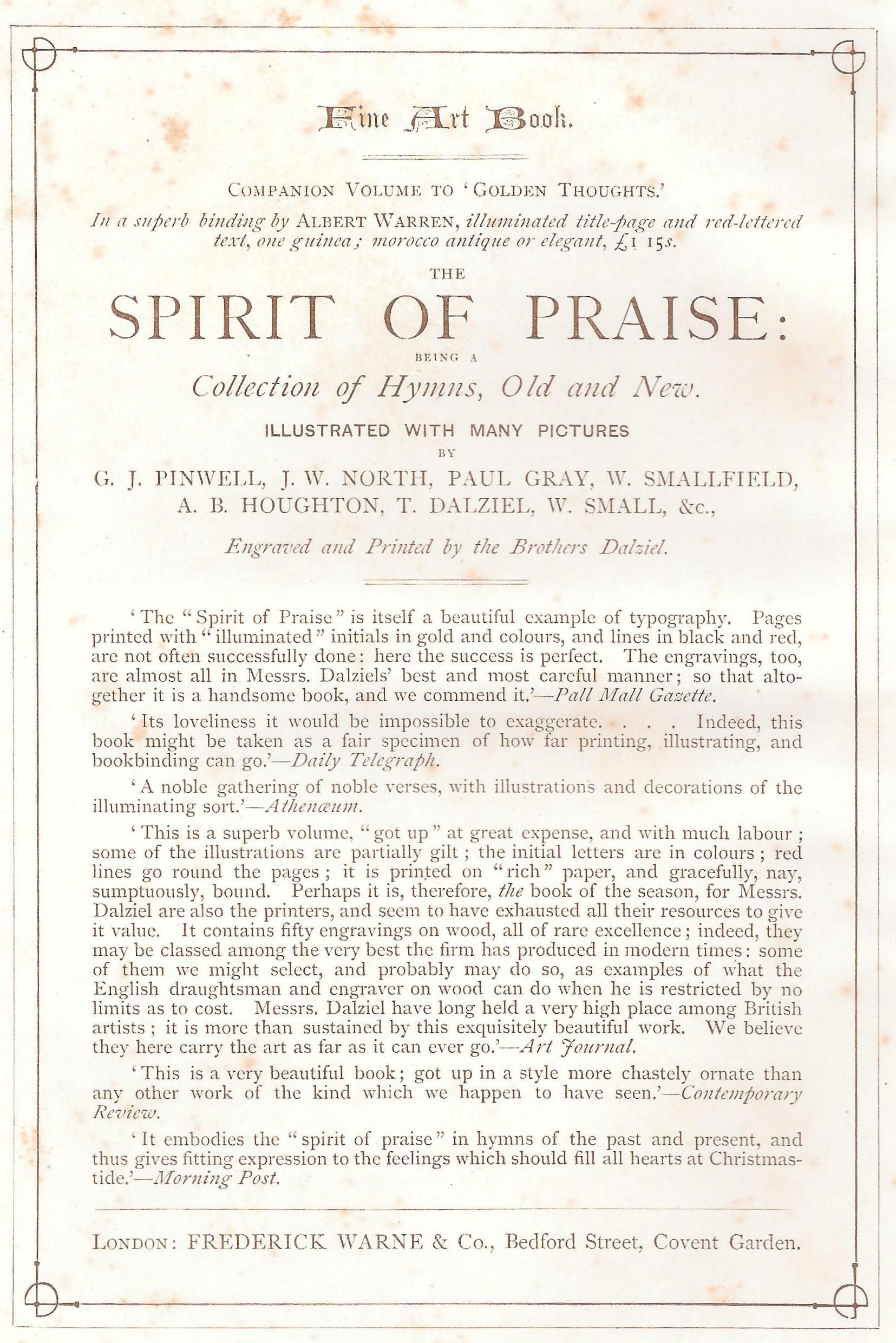

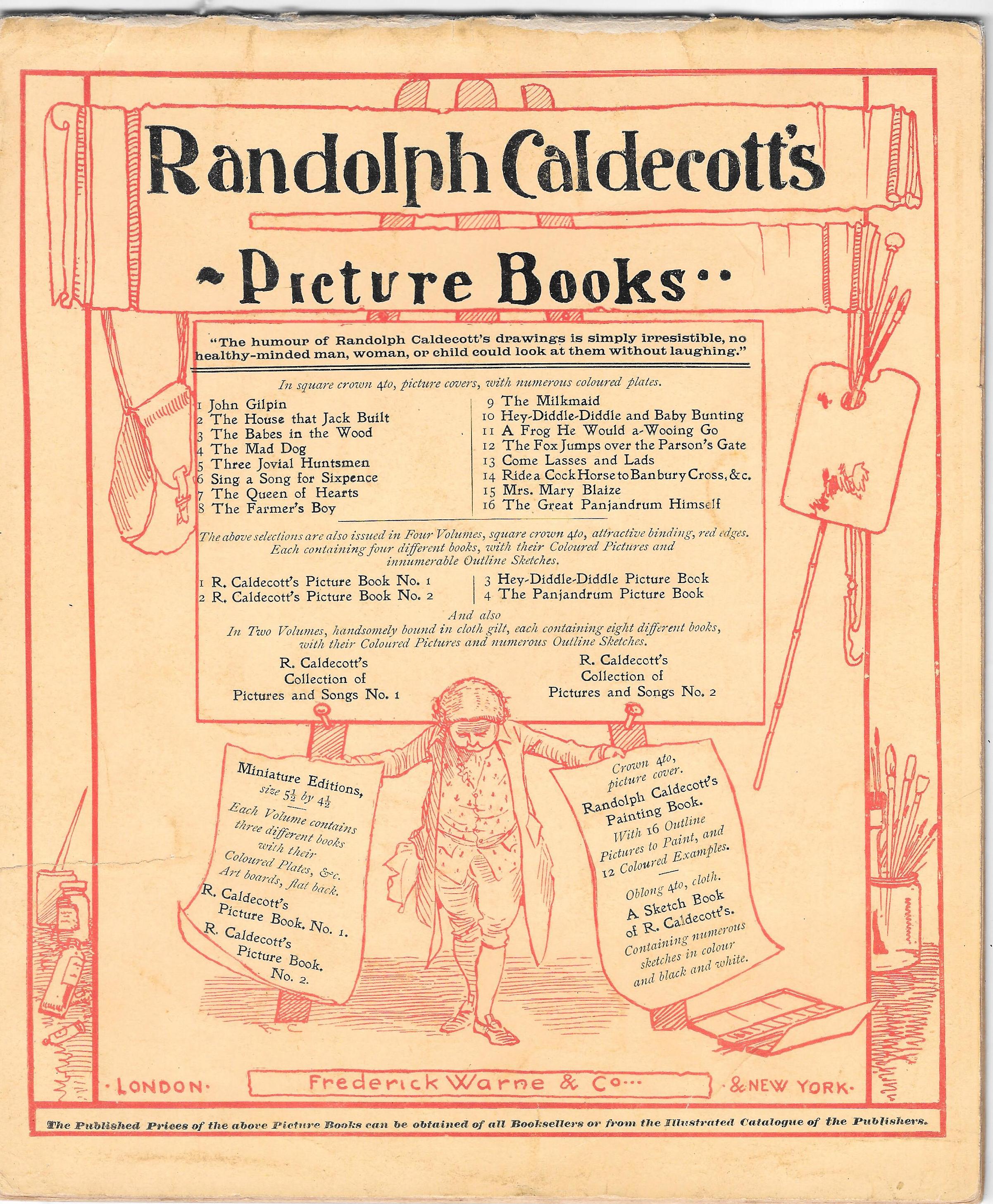

Such overstated promotion is matched to some degree by the advertisements appearing in Victorian fiction, history, poetry and other volumes with a serious content. In the middle period, it was commonplace for imaginative literature to include publishers’ catalogues, and while many are simply lists it is not uncommon for books to be promoted by reprinting critical notices, many of them sustained over half or three quarters of a page. An advertisement for Le Fanu’s The House by the Churchyard epitomizes this approach; instead of presenting short critical comments, it reprints a lengthy section from a notice. The same approach is used in gift books, several of which contain extensive reviews of parallel publications. At the rear of Golden Thoughts from Golden Fountains [1867] is a typical prompt, encouraging the reader, having perused Thoughts, to consider its companion, The Spirit of Praise. The hard-sell is unashamedly boastful, selecting a series of favourable comments and (of course) omitting the negatives.

Left: Advertisements for Dalziels’ Gift Books, The Spirit of Praise, and Randolph Caldecott’s Picture Books. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Dense, over-written and crammed into small fields, these advertisements reflect the congested state of the mid-Victorian market-place: with so much to sell, their crammed columns are the linguistic equivalent of glut. In a curious way, they echo the fear of space, the desire to fill up a vacuum, the need to create redundancy, that is so much a part of Victorian culture. In the later period, however, the number of words declines and imagery becomes the prime means of promotion.

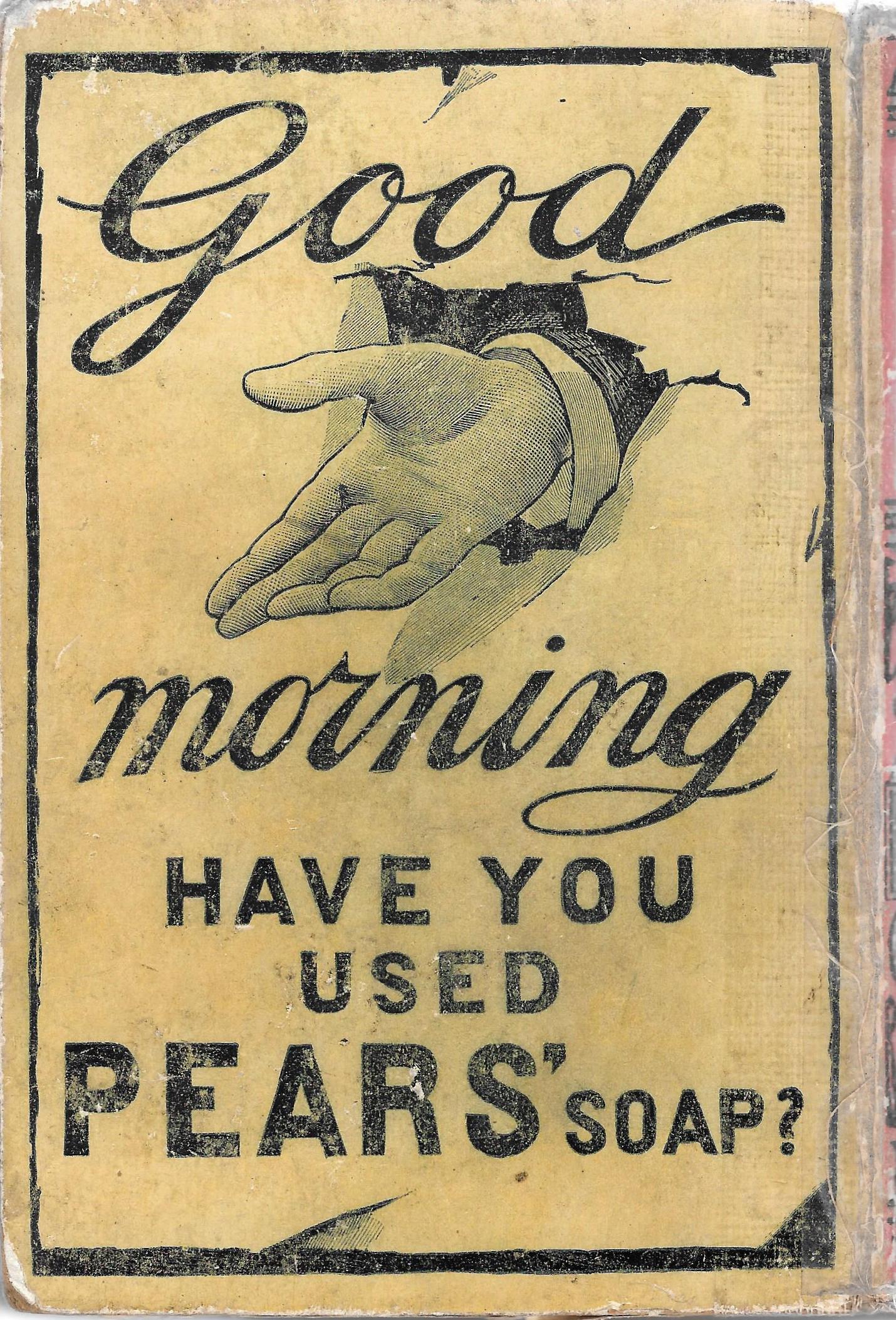

Another interesting development is the manner in which later Victorian publications dissolve the distinction between magazine and book, with miscellaneous advertisements, usually only found in journals, appearing in the endpapers and sometimes the covers of cheap literature. The more sophisticated, visualized displays of the final decades of the century are typically found in yellowbacks, the inexpensive novels associated with railway journeys. Sold in platform kiosks and in newsagents in urban streets, yellowbacks contain a wide range of simplified, hard-hitting images selling diverse products. A prime example is the back cover of a yellowback representing an extended hand (apparently bursting through the paper) with the greeting ‘good morning’ followed by a simple demand: ‘have you used Pears’ soap’? The implication is that no-one will want to shake a hand that hasn’t been washed by the aforesaid product. Published in the eighteen nineties, this is the very model of a modern advertisement: personalized in its deployment of a question and pronoun, condensing its message in a simplified form and sophisticated in its interplay of image of text, it contrasts with the information-based commercials of the earlier part of the century, and anticipates future developments.

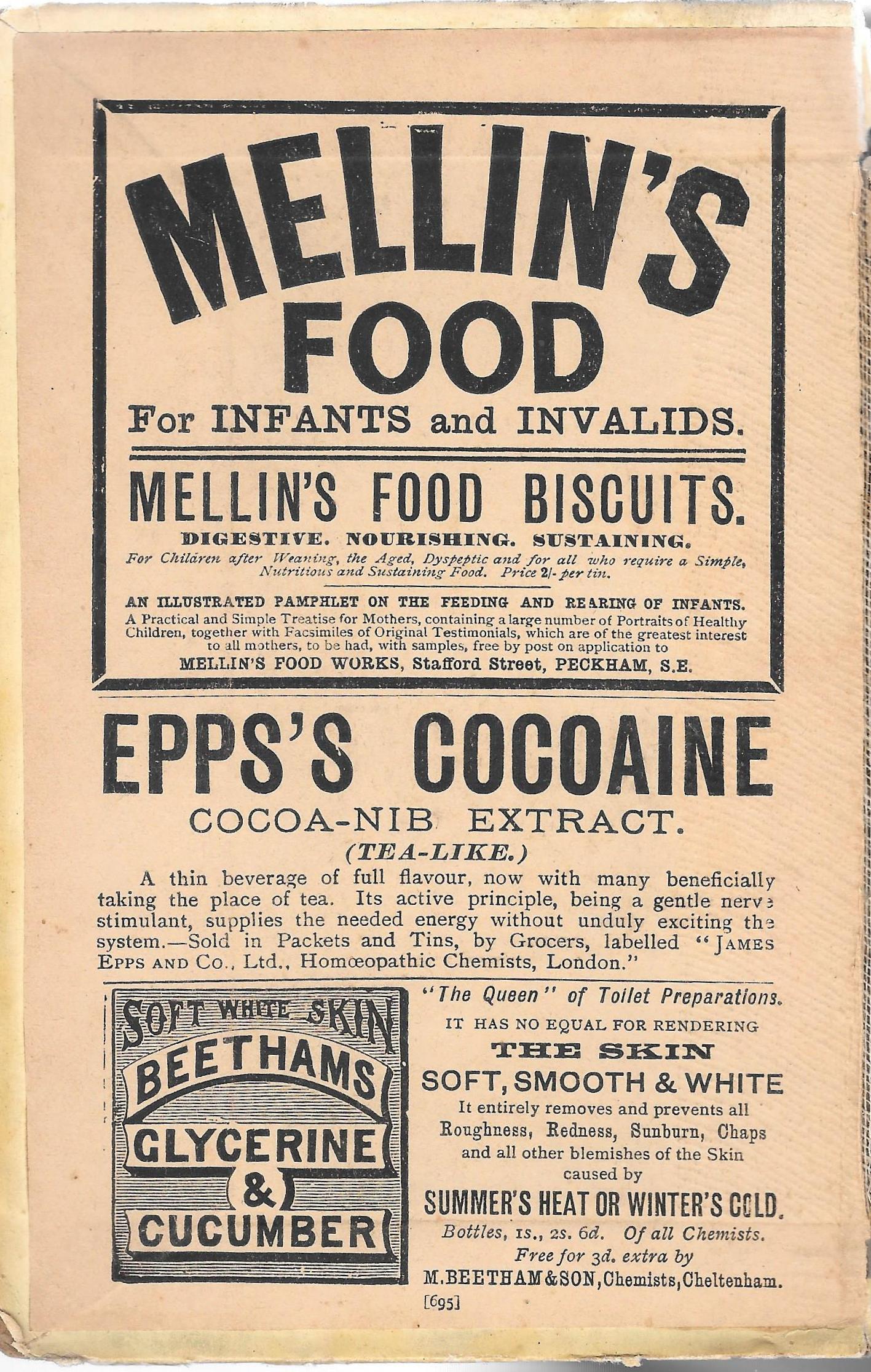

Product Advertisements. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Advertising and Reading

ow the Victorians read their texts is a problematic issue. Reading practice has been examined by generations of critics from diverse perspectives, although the only conclusion arising from these analyses is that it involved a multiplicity of interpretive strategies. Of key importance is the Victorian reader’s negotiation of writing and illustration: sometimes characterized as a matter of the moving eye which glances to and from the two sets of text, the experience of inter-medial interpretation recasts the reader as the reader/viewer whose understandings involve a complicated synthesis. Textual and paratextual information fuse into one, and in the most effective works it is difficult to privilege one before the other.

More problematic, perhaps, is the relationship between the written text and its framing advertisements, which have a significant impact on the ways in which the material is read. The most detailed analysis is offered by Sara Thornton, who focuses on the dense commercialization of Dickens’s monthly numbers. Her reading of the serial parts of Our Mutual Friend(1865) is clearly explained in a review by Nicholas Mason, who notes how

Thornton is most interested in the Dickens Advertiser, the intricately designed monthly numbers of Dickens’s novels where the fictional text is immersed in a sea of advertisements. In some cases, such as the first number of Our Mutual Friend, the Advertiser edition devotes more than twice as many pages to advertisements as to the novel itself … her chapter on the Dickens Advertisers probes the ‘complexity of perpetual skills demanded of the reader’ when the primary text is regularly interrupted by commercial paratexts. The new mode of reading that emerges, she suggests, amounts to a sort of literary ‘grazing’ or ‘loitering’, a forced attention-deficit disorder where the ‘oriented and organized linear reading associated with the novel’ (65-67) is radically disrupted.

This ‘loitering’ is essentially a matter of disruption, a breaking up of messages which is quite unlike the intimate intertextualities of words and illustrations. Although she does not spell it out, Thornton’s analysis identifies a function of all advertising to steal our attention, as it were, in the way that television programmes are interpolated with advertisements and articles on the internet are combined with commercial information. This approach stresses the fragmentation of the Victorian readers’ responses in an age when rapid change, restlessness, instability and sensory overload were a central part of a culture both dynamic and fraught with anxiety as the latest fashion – or ‘craze’, as the Victorians called such phenomena – succeeded the last.

There are other points of interaction as well. In literary magazines the advertisements have a number of effects. One issue is gender. Sometimes commercials are used to reinforce the journal’s orientation towards a particular audience and it is notable that early numbers of The Cornhill Magazine appeal to a largely male audience by including advertisements for masculine consumers of beer, spirits, ‘Chubb’s patent safes’, shirts by Bowring and Arundel, patent metallic pens and gentleman’s watches. In Once a Week and The Quiver, on the other hand, the full-page texts and semi-displays are almost entirely domestic in content, directing a series of practical messages to the middle-class wife who directs the running of her home. Singer’s sewing machines, Epps’s Cocoa, insect destroying power, furniture, medicines and innumerable medicines for children are the focus of these pages. Taken as a whole, the advertisements underscore conventional gendering and help to place the magazine in a particular market niche, although it is also the case that some journals signal their appeal to both sexes by dividing their advertisements into cradles and cigars.

What the commercials always do is commodify the texts they enclose. Thornton emphasises the breaking up of the reader’s response, and in so doing the advertisements alert the interpreter to the fact that s/he is engaging with a text which is itself a product. Framed by catalogues of objects, the literary parts of the journals are presented as just another thing to be purchased and consumed. The advertisements act, we might say, to reinforce the capitalist nexus in which the magazines operate, making the reader into a consumer of words and images. In Marxist terms, the commercials facilitate the infiltration of all aspects of life and reduce art and the promotion of ideas, in the form of literary texts and articles, to just another consumable. The effect is often disconcerting, with random juxtapositions of literature and starch, or literature and ale: a form of debasement, arguably, which is especially marked in the intermingling of canonical texts by Dickens, W. M. Thackeray and George Eliot and advertisements for cheap commodities. It also, of course, suggests the mental flexibility demanded of a contemporary reader who might shift, as happens in the opening number of The Cornhill, from ‘Brighton Ale’ and notices selling indigestion pills, to the first pages of Eliot’s ‘Romola’ and Frederic Leighton’s opening design. Such incongruity – simultaneously immersing the reader in the worlds of Renaissance Florence and the contemporary experience of drinking a pint of beer – is achieved in the flicking of a page, and typifies the collapse of discrete notions of taste and the difference between Trade and Art which characterizes the rise of bourgeois culture in the nineteenth century.

When it comes to books, however, the effect of advertising is not a matter of fragmentation, but its reverse. Rather, publishers included catalogues of their imprints not only (and obviously) to sell more books, but also to suggest that readers were part of an elite club. This is especially true of the advertisements appearing in gift books, where the reprinting of laudatory reviews is a calculated piece of flattery, converting the consumer into a connoisseur. These are the types of books that would appeal to you, the advertisements insist; you are one of the readers of the highest standards of taste. These commercials work, in other words, to reinforce the middle class readers’ desire for cultural capital – essentially selling books by emphasising their special qualities and (more importantly) the special qualities of their readers. This notion of inclusivity is of course a key constituent of the wider discourse of advertising, and, as we have seen, the paratextual material appearing in Victorian publications establishes many of the tropes of the modern age.

Works Cited

Carlyle, Thomas. Past and Present (1843). Available in the Internet Archive.

The Cornhill Magazine, 1860–70.

Golden Thoughts from Golden Fountains, London: Warne [1867].

Thornton, Sara. Advertising, Subjectivity and the nineteenth-century novel: Dickens, Balzac, and the Language of the Walls.’ [Review by Nicholas Mason]

Once a Week, 1860–70.

The Quiver, 1875.

Richards, Thomas. The Commodity Culture of Victorian England: Advertising and Spectacle, 1851–1914. Stanford: University of California Press, 2000.

Thornton, Sara. Advertising, Subjectivity and the nineteenth-century novel: Dickens, Balzac, and the Language of the Walls. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Created 25 July 2019