lfred William Cooper (1828–1916) was a prolific artist who made a significant contribution as an illustrator of mid and later Victorian books and magazines, while also conducting his main career as a painter of landscapes and domestic scenes. His life and art have never been the subject of scrutiny; his paintings, which regularly appear for sale, do not appear in any accounts of the period, and his illustrations, though mentioned in the studies by Forrest Reid (1928) and Gleeson White (1897), are not considered in detail.

In this article I establish the main biographical facts, explain his illustrative style, and place his work within the contexts of contemporary book-art. In particular I want to show how Cooper was in some of his work at least a sophisticated artist who used his images to reflect on aspects of Victorian culture.

Cooper’s Life

Usually identified by his initials ‘A. W. Cooper’ or ‘A W C’ rather than his full name, Cooper was born on 23rd October, 1829. His background was middle-class and relatively wealthy; his father was the landscape and animal painter, Abraham Cooper, R.A., and the family’s home, in St Pancras, London, was a comfortable address in what was then a rural village on the outskirts of the capital.

Little is known of Cooper junior’s early life, and there are no records of his training. He does not seem to have attended one of the London art-schools and may have been taught at home by his father. This arrangement was not unusual in ‘artistic families’; for example, the comic illustrator Richard Doyle’s was educated by his his artist-father (Engen15). Certainly, Cooper’s early illustrative work is stilted and amateurish, a quality suggestive of a lack of formal training, and a judgment especially applicable to his designs in his first book, Mrs Henry Lynch’s The Family Sepulcre: A Tale of Jamaica [1848]. Lynch’s tome was co-illustrated by Cooper senior – who may have secured the commission by offering himself as a reputable name – and there is marked difference between the father’s well-practised drawings of fauna and landscapes and the son’s inexpert figure modelling.

Nevertheless, Cooper’s skills quickly improved, and he was soon offered diverse opportunities in the expanding book-trade of the middle of the nineteenth century, becoming one of the numerous journey-men artists who supplied wood-engraved images for books and magazines. His designs appeared in London Society, The Churchman’s Family Magazine, Tinsley’s Magazine, Once a Week Aunt Judy’s and The British Workman, along with numerous small-scale commissions for children’s books. These piecemeal jobs, paid at £10–£15 per design for whole page illustrations and as little as £5 for vignettes, were a significant strand in his overall work and helped to supplement his earnings as he struggled with the vagaries of art market.

Between 1854 and 1864 he exhibited 62 paintings at the R.A, the British Institute, Suffolk Street and the New Galleries (Redgrave 62); he may have had sales, but the combination of incomes was a good move and the dual-strategy, so typical of many of the artists of the period, seems to have worked. Although he was still living with his parents in 1851, when he was 22, by 1871 he had his own address in Twickenham and, it seems, had become a successful man; he married in 1870 (aged 41) and the couple produced three children. The rest of his life was spent firstly at number 4 Manor Road, and later at 6; these were well-appointed houses and the Coopers’ wealth is also suggested by their having two servants.

This economic status allowed the family to move in fashionable circles, but always had to be supported by significant industry. From 1870 to the end of the century the artist was continuing to exhibit and gain commissions for his paintings, but it is interesting to note that these were his most productive years as an illustrator. During the years 1872–96, he worked on a wide range books and contributed to several periodicals. His publications were mainly for children, but he also designed for The Graphic and the Evangelical imprint by Partridge, The Weekly Welcome. Some were commissions executed as black and white engravings on wood and some in the vivid palette of chromolithography. The editions of The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (1896) and Stories for Mamma to Read (1886) are good examples, and for his colour books he painted the designs in watercolour to assist the chromolithographer; at least one, for The Arabian Nights, survives. Working through these various projects, Cooper established himself as a versatile practitioner. His name was always used as a selling-point in advertisements, and his art, as the product of another safe pair of hands, appealed to a wide audience.

A pen-portrait by Cooper of Keene in fancy-dress for one of Birket-Foster’s theatricals – here dressed, perhaps, as Chaucer.

He also seems to have been popular with his fellow-artists, and was an associate of several coteries. He was a close friend of the illustrator Charles Keene; they shared a tent as volunteer riflemen for the South Middlesex Corps (Layard 70) visited mutual friends together, and went on fishing trips (359–60) where Cooper demonstrated an expert knowledge of the intricacies of angling. Cooper and Keene were also in the inner circle of Myles Birket Foster, which included the engraver Edmund Evans – who engraved much of Cooper’s work – and the artist/designers, Fred Walker, J. D. Watson and Robert Dudley. The friends dressed up and took part in amateur theatricals, played music together – Cooper was a violinist – threw elaborate parties at Foster’s house, ‘The Hill’ in Witley, Surrey, and went on continental holidays, where Cooper was scandalized by Birket Foster’s incompetent French and comical mistranslations. Cooper was regarded as a wit and entertained his friends with droll conversation and pranks, on one occasion playing discordant music to mock the professional musicians’ tuning at one of the artists’ Christmas events (Layard 138). For Keene, as for Birket Foster, Cooper was always a ‘very great’ companion (138) and their social relationship was embodied in the production of art. He made a drawing of Keene in medieval costume (National Portrait Gallery, London) and painted a watercolour of the kitchen at ‘The Hill’. He also collaborated with Birket Foster on the painting of the pub sign for ‘The White Hart’ in Witley (Reynolds 131); it is now preserved, the unlikely record of a friendship, in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Sociable, well-liked and professionally successful, Cooper seems to have enjoyed a fulfilling life. In his final years he retired from painting and illustration and lived modestly in the family home in Twickenham; he and his wife seem to have looked after themselves without servants, and by 1901 their children had left home. He died while visiting the Isle of Wight on 28 February 1916, aged 85.

Cooper’s Art: Leisure and Pleasure in the 1860s

Cooper mainly practised in the idiom known as The Sixties, which dominated the mid-Victorian period and was characteristically associated with wood-engraving. This poetic realism, with its emphasis on reproducing the formal qualities of painterly verisimilitude in the small domain of the page, was carried forward by J.E. Millais, Arthur Boyd Houghton, J. D, Watson, George Pinwell, Fred Walker and Fred Sandys. Cooper, as one of the lesser artists, contributed to the discourse established by his more famous contemporaries. A friend of several of these figures and familiar with their work, he shared in a common aesthetic, although his style was never imitative or static. Rather, he was willing to move with the times, and in the later period, from the seventies into the nineties, drew in a looser manner which emphasised atmospheric effects rather than line and modelling. Much of this work seems uncomplicated and generic, but a close reading reveals a nuanced approach to his subjects.

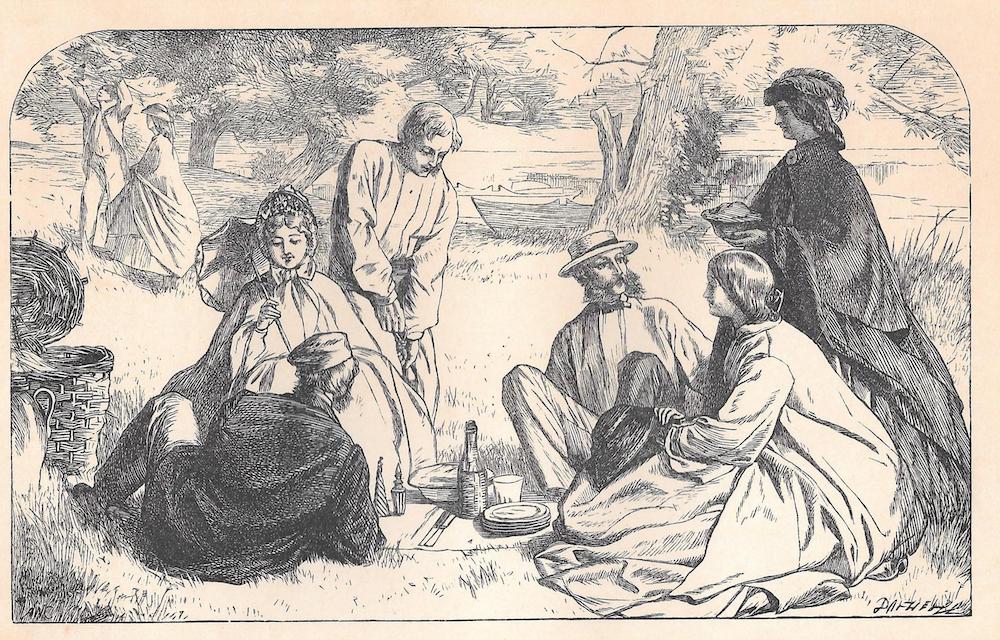

Cooper’s illustrations in the style of the Sixties were focused on a typical concern of the period: the lives of the middle-classes, with a special emphasis on bourgeois leisure, pleasure, and the importance of romance and domestic relationships. Most notable are the lyrical designs he did for London Society, each of which makes a strong appeal to the well-heeled readership by offering vivid representations of domestic life and the rituals of repose. In The Pic-nic, for instance (1865), he shows a group of mid-Victorians engaged in what the accompanying text describes as a sharing of pleasure in the great outdoors, with figures assembled around a table-cloth furnished with food and drink; one opens a bottle, one holds a pie and a couple in the background are trying to pull something (apples?) from a tree. Cooper depicts the characters as well-dressed and relaxed, engaged in conversation as they commune with each other and with nature. It is a casual scene, intended to illustrate an episode in an undistinguished account of ‘A Holiday’, but Cooper makes the characters, especially the women, in their elaborate dresses, into monumental types; arranged in the manner of painterly composition, their poses are echoed and reinforced by the rhythmic arrangement of the trees in the background. The effect is one of classical stillness, alluding to the Renaissance exemplars of Titian and especially Le Concert Champêtre (1510, Louvre, Paris) in which the figures, this time fully-dressed, are Victorian equivalents to the Italian painter’s Arcadian cast of idealized types. This approach infuses the ‘modern’ with significance, aligning the contemporary revellers with the universality of a mythologized past and takes them beyond the words of the accompanying article. Modernity is also suggested by the connection between Cooper’s design and the rural idylls of Watteau, as he celebrated the leisure time of the privileged in country settings.

Cooper’s idyllic representation of The Pic-nic.

Cooper is equally interested in commenting on Victorian mores and the associations of the countryside. Depicting the rural as a paradise, he emphasises nineteenth century attitudes to nature, articulating the idea that a retreat into the country was a refreshing escape from the facts of urbanization and busy metropolitan life. His escapist imagery was also an assertion of national values, of England as an idyll peopled by prosperous inhabitants. His image of the picnickers is in this sense a patriotic text: as one critic observed when his London Society illustrations were re-issued in Pictures of Society, Grave and Gay (1865), the artist combines landscape with ‘sturdy, manly men and fresh, lovely, high-bred women … all of which are unmistakeably English’ and project an idea of ‘England at her best’. This approach appeals to and reinforces the original reader/viewers’ orthodox beliefs in social hierarchy and the stability of an ‘England of the rich, not the poor’ (‘Pictures of Society’, Round Table 202)

However, Cooper adds another dimension in teasingly suggesting the sexual politics inherent in the pursuit of rural pleasure. This idea is considered by the writer of the second text which accompanied the illustration when it was republished in Pictures of Society (1865). Having arrived at the rural site, Cooper’s characters engage in play as it is described by the commentator ‘JAS’:

The usual gambols and flirtations follow … after a while it is found that Charley and Clara have disappeared; then Harry and Kate start in search of them, Fred takes pretty Annie for a pull on the river, and each happy pair commences the pursuit of pleasure on its own account. [Pictures of Society, 18 ]

Cooper embodies this idea in his composition of young men and women lounging and talking to each other, perhaps flirtatiously; a couple in the left background have already gone off together, and perhaps the others will too. Indeed, Cooper produces several other idyllic scenes in which he makes an explicit linkage between rural leisure, courtship, and marriage. In On the Hills (The Churchman’s Family Magazine, 1863), he shows a contented couple positioned in another idyllic landscape. The image is accompanied by an anonymous poem and embodies its interconnectedness of nature and harmonious love: the poet writes of ‘Emblems of love’, and Cooper shows the characters looking affectionately at each other, at one with each other and at one with nature. In Drifting the metaphor is taken further, as a couple’s uncertain relationship is suggested by their floating on a stream, and in At Anchor he suggests the harmonies of married love and parenthood, with a contented young father looking at his wife and children as they float comfortably on a still river; the proud paterfamilias, he still has time to have a smoke.

Two idealized illustrations by Cooper. Left: The romantic vision of On the Hills; Right: Drifting. In both designs, Cooper creates another version of the English idyll.

Cooper at his sweetest: At Anchor.

All of these designs of rural pleasure and leisure are resonant images of the bourgeois idyll, symbolized by leisured characters in idealized landscapes. The iconography is related to Watson’s ruralism, and there is clearly a connection between Cooper’s imagery and designs such as Watson’s Blankton Weir and An Evening Stroll. Cooper also shares Watson’s intense aesthetic effects, offering a self-consciously beautiful version of a poetic domain which is as much a state of mind as a place. This Romantic focus links him to the ‘Idyllic school’ of the Sixties, assigning him a place next to North, Walker and Pinwell.

Later Developments

Cooper’s illustrations of the sixties are prime examples of the carefully-modelled, heavily-blocked designs cut by the Dalziels and Harral. They are striking pieces, poetic and understatedly suggestive of a harmonious life, the emblems of the relative stability of the mid-nineteenth century. Cooper’s later work was less homogenous and focused. Responding to economic need, he serviced diverse publications in styles that varied between the journalistic and the lyrically child-like, producing complete series and single frontispieces, wood engraved designs both black and white and hand-coloured, and images reproduced lithographically and using chromolithography; he also designed several book-covers, creating a fusion between the publications’ exterior and interior.

Cooper was one of the artists recruited by William Luson Thomas to illustrate the Graphic newspaper when he set it up in 1869, and like others contributing to its pages created documentary engravings of contemporary life. However, unlike Luke Fildes, Hubert Herkomer, Frank Holl and William Small, who focused on issues of class and social injustice, Cooper’s central concern, as in the sixties, was on bourgeois leisure, this time representing the practice of blood sports. He did several composite tableaux which depict the shooting of exotic animals in India – images worked up from photographs – but was most effective in his observations of the home-spun sport of fishing. The Contemplative Man’s Recreation; Fishing at Teddington Lock (Graphic, 3 September, 1892) exemplifies his journalistic approach: stripped of the poetic atmosphere of his earlier river-scenes, the image is purely a record of the business of leisure, with a row of fishermen crowded together at the bankside, with boats on the water and a character at the left hand side once again smoking a cigarette. Cooper’s low-key, suburban realism, observing but making no political or didactic comment, is vividly immediate, catching a moment of late Victorian life in a direct, almost photographic style. The same is true of his detailed record of types of fishing and hunting in his illustrations for Francis Francis’s Sporting Sketches with Pen and Pencil (1878). The author notes in his preface how Cooper ‘has a thorough knowledge of Sport in all its branches and of the implements and requirements needed for its prosecution’, and this expertise is embodied in rural scenes of the inedible in pursuit of the edible. Here, as in the work for the Graphic, the impression is one of sophisticated observation, enshrining an historical account of how middle-class men filled their down-time.

Cooper’s journalistic take on sporting events. Fishing at Teddington Lock.

His reporting of another sporting event from 1878.

In complete contrast are Cooper’s later books for children, of which he produced a considerable number. These were both exotic and domestic: The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (1896) is in vivid chromolithographic colour, depicting oriental scenes in the boys’ adventure style associated with Victorian concepts of the East, while Found at Eventide (1872), The Martyrdom of Madeline (1889) and Who Did It? (1882) are closely observed portrayals, engraved in black and white, of contemporary domestic life and its rituals. The most accomplished of these later books is Mrs Sale-Barker’s Inmates of Our Home (1888). For this publication Cooper designed the chromolithographic cover and the illustrations in lithographic grisaille. These designs show the lives of children in a series of lyrical interiors and in the form of rural settings. Again making the link between landscape and leisure, his illustrations are a version of the imagery of his paintings, and represent a departure from his nature engravings of the Sixties, being much looser and impressionistic in effect than his earlier designs.

A water-colour produced for

The Arabian Nights

Cooper might thus be described as a versatile artist who employed a variety of idioms and techniques. At once a realist, with a sharp eye for social nuance and the intricacies of the everyday life of his time, he was also an idealist whose images of rural leisure suggest timelessness as well as the here-and-now; his illustrations of childhood, likewise, are sensitive treatments of their subjects. All of his work is carefully conceived. Another visual poet of his time, Cooper deserves to be better remembered than he is, and should be promoted from his usual position in the footnotes.

A Note on Biography: Cooper’s biographical details have been retrieved from the online Census returns available in Ancestry.co.uk

Bibliography

Note: The following is a outline of publications that were illustrated or co-illustrated by Cooper. This is very much a tentative listing, and there is currently no complete catalogue of his work.

Adams, H. C. Who Did It? Or, Holmwood Priory. London: Dutton, 1882.

Allen, Phoebe. Two Little Victims. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge [1891].

A.L.O.E. [Charlotte Maria Tucker]. Proved in Peril, or, The Shield of Faith. London: Gall & Inglis, 1879.

Andersen, H. C. Fairy Tales and Sketches. London: Bell, 1875, 1884.

Andersen, H. C. Later Tales. London: Bell & Daldy, 1869.

Andersen, H. C. Our Favourite Nursery Tales. London: Warne [1883].

[Anon]. Arthur Morland. London: John Morgan, 1867.

[Anon]. Stories for Mamma to Read. London: Nelson, 1886.

The Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. London: Routledge, 1896.

Aunt Judy’s Magazine (1866).

The British Workman (1865).

Buchanan, Robert. The Martyrdom of Madeline. London: Chatto & Windus, 1882.

Burnside, Helen M. A Day with the Sea Urchins. London: Warne, 1893.

Chiswell, Alfred. The Slave Prince. London: Griffith & Farran, 1890.

The Churchman’s Family Magazine (1863).

Dalton, William. The White Elephant. London: Griffith & Farran [1898].

De Liefde, Jan. The Postman’s Bag and Other Stories. London: Hamilton, 1863.

Fenn, George Manville. The Weathercock. London: Griffith Farran, 1892.

Francis, Francis. Sporting Sketches with Pen and Pencil. London: The Field Office, 1878.

Goddard, Julia. The Boy and the Constellations. London: Warne, 1866.

The Graphic (1871–1892).

Keepsake for the Young. London: Warne [1871].

London Society (1862, 1865, 1868–69).

Lynch, Theodora E. The Family Sepulcre: A Tale of Jamaica. London: Seeleys [1848].

Marshall, Emma. Rainy Days. London: Partridge [1863].

Martineau, Harriet. The Playfellow. London: Routledge [1880].

Miller, O. T. Friends in Fur and Feathers. London: Bell and Daldy, 1869.

Once a Week (1863).

Pictures of Society, Grave and Gay. London: Sampson Low, 1866.

Reade, Charles. A Terrible Temptation. London: Chatto & Windus [1883].

Sale-Barker, Lucy. Holiday Album for Girls. London: Routledge, 1877.

Sale-Barker, Lucy. Inmates of Our Home . London: Routledge, 1888.

Sale-Barker, Lucy. Puff, the Pomeranian. London: Routledge [1885].

Taylor, Charles B. Found at Eventide. London: Religious Tract Society, 1872.

Tinsley’s Magazine

The Weekly Welcome(Jan–June, 1879). Engen, Rodney. Richard Doyle. Stroud: The Catalpa Press, 1983. Graves, Algernon. The Royal Academy of Arts. A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904. London: Henry Graves-George Bell, 1906. Layard, G. S. The Life and Letters of Charles Samuel Keene. London: Sampson Low, 1892. Pictures of Society, Grave and Gay. London: Sampson Low, 1866. ‘Pictures of Society, Grave and Gay.’ Round Table 2 (December 2 1865): 202. Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; rpt. New York: Dover, 1975.

Reynolds, Jan. Birket Foster. London: Batsford, 1984. White, Gleeson. English Illustration: The Sixties, 1855–70. London: Constable, 1897. Created 18 January 2023Secondary Material