he Yorkshire Philosophical Society was founded in 1822. Its purpose was "to collect and diffuse information on the Antiquities, Geology, and Natural History of the County, — by the establishment of a Museum and Library and the holding of periodical meetings" (Hume 146).

The finding in a cave of exotic animal bones, which some believed were evidence of the biblical Flood, was a powerful stimulus to the formation of the Society. This had happened in the previous summer. In July 1821, the Yorkshire-born manufacturing chemist, John Gibson, was up from Essex visiting friends, and happened to pass a party of workmen filling in potholes. Like so many at this time, Gibson was fascinated by fossils, and knowledgeable about them too — knowledgeable enough to recognise some unusual fragments in the heap of filling material — "among the bones were those of hyenas and bears: not animals generally found in Yorkshire. Questioning the roadmenders, he established that these came from a nearby quarry, close to the church of St Gregory, Kirkdale" (Hogarth)

Kirkdale Cave specimens, left to right: (a) Leg joint from bison. (b) Hyena jaw. (c) A gnawed bone. Images courtesy of York Museums Trust: https//yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/ CC BY-SA 4.0.

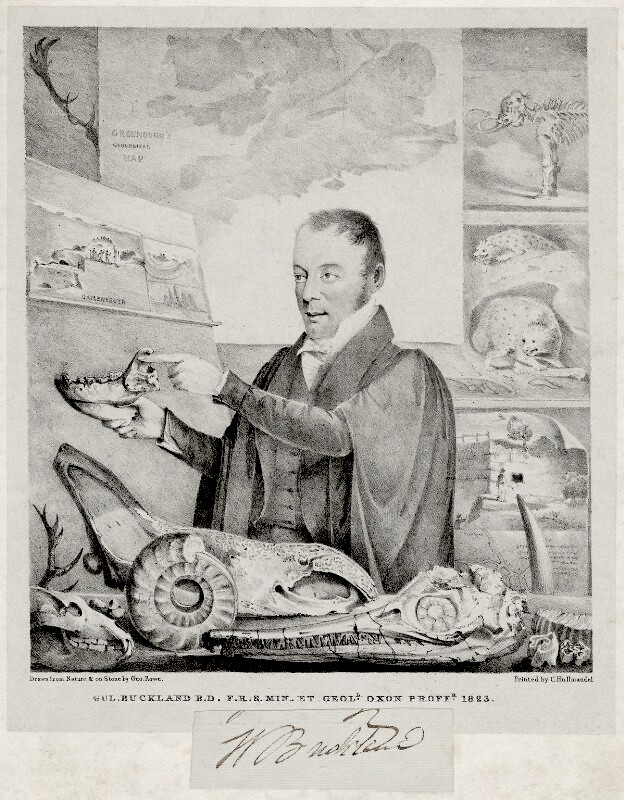

News of the finds eventually reached the Rev. William Buckland, Reader in Geology and Mineralogy at Oxford, who visited the cave where they were found in December 1821, and began a systematic study of everything of interest that was found there, and wrote about them in his Reliquiae Diluvianae of 1823.

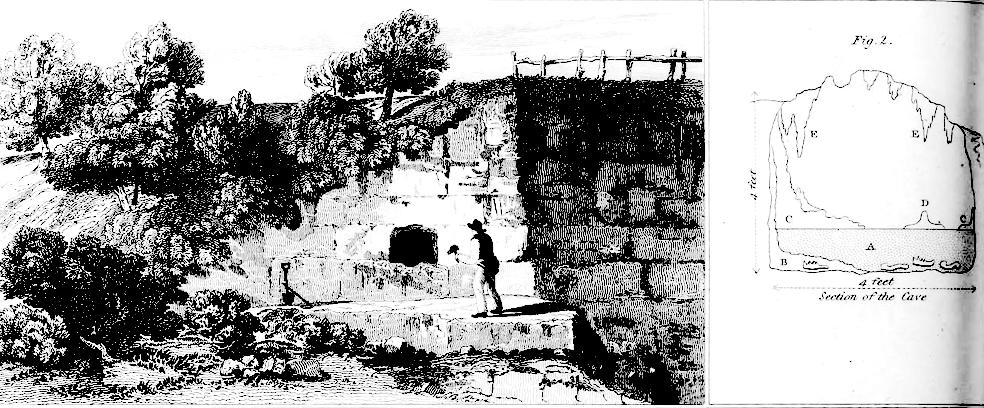

Plate II in Buckland's Reliquiae Diluvianae: "View of the mouth of a cave at Kirkdale, in the face of a quarry, near the brow of a low hill."

Indeed, Plate I in Buckland's book is simply a map of the countryside surrounding the Kirkdale Cave. Next to the graphic presentation of the cave is a ground-plan of it by William Salmond (1769-1838), one of the three founding members of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, society, "showing its extent, ramifications, and the fissures by which it is intersected" (no page number).

Portrait of William Buckland, 1823, by George Rowe, printed by Charles Joseph Hullmandel, lithograph reproduced by kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG D7669).

By the time the book appeared, the Yorkshire Philosophical Society had already been founded, with Salmond and his two fellow founding-members combining together "their private collections in order to form a Museum" in 1824 (Hume 146). At first they found accommodation for their items in a bank, but the bank failed while the collections continued to expand (see Hogarth and Anderson, 1-2). Then in 1828 a part of the grounds of St Mary’s Abbey was given to the Society by royal grant. The Yorkshire Museum was built there in 1829 to house the collections, and the Society also established a botanic garden.

The society flourished. Abraham Hume explains, "In 1831 the first meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science was held at York, when Earl Fitzwilliam (then Viscount Milton) united in himself the offices of President of the Society and President of the Association"; Hume also mentions that "in 1843, Stephen Beckwith, M. D., bequeathed to the Society the sum of £10,000 (146). By the time Hume was writing, the society had 300 members, and their museum had not only a library but an observatory.

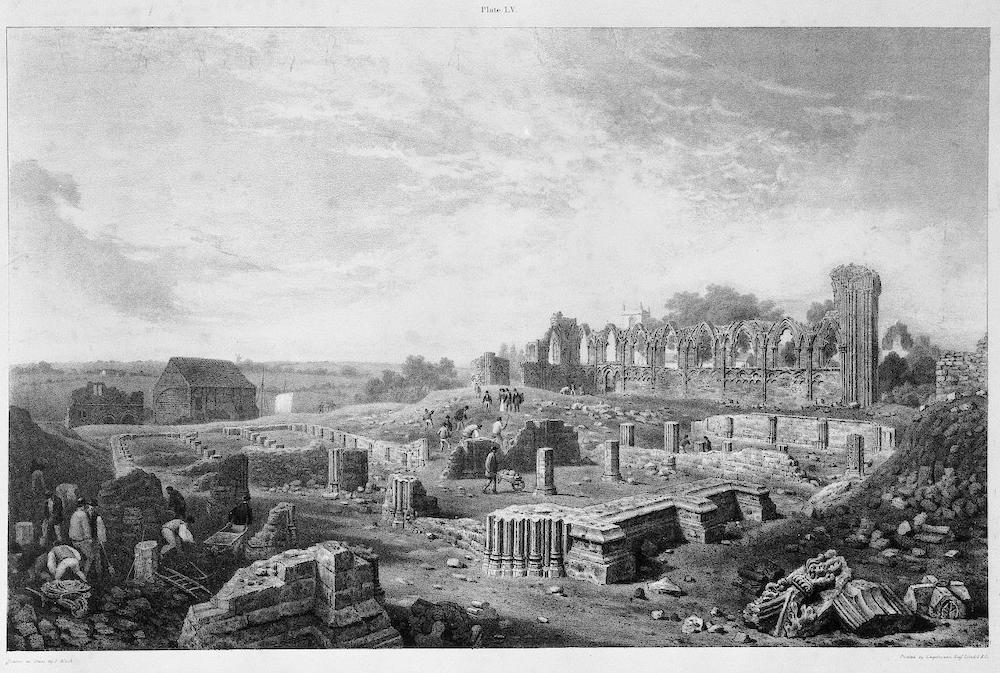

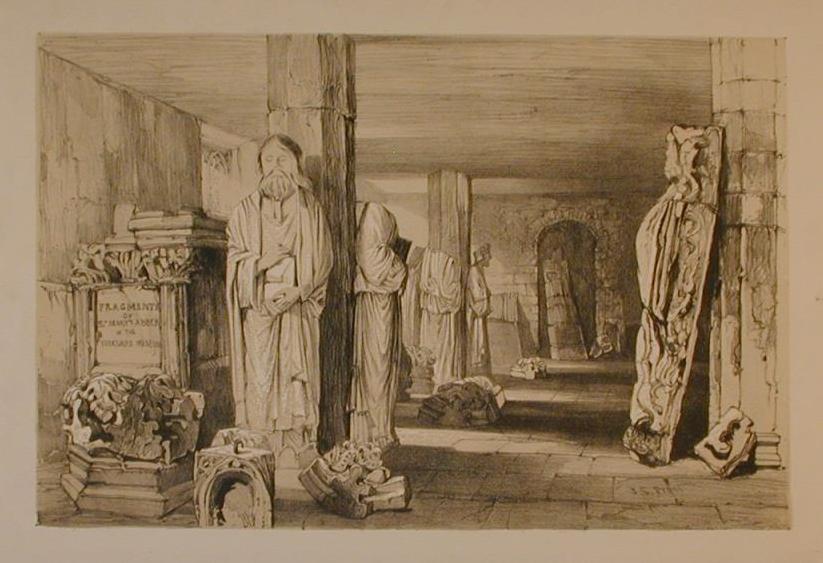

Left: F. Nash (Artist) and Charles Hullmandel (Printer), published by the Society of Antiquities [mistake for "Antiquaries"?], dated 1829. Right: Samuel Prout's drawing, c. 1820-50, “Fragments from St Mary’s Abbey in the Yorkshire Museum.” Both images courtesy of York Museums Trust: https//yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/ CC BY-SA 4.0.

There were certainly materials for archeologists at York. The lithograph on the left, above, shows workmen excavating the ruins of Saint Mary's Abbey in the foreground. Beyond the excavations is the still-standing north wall of the abbey church. The bases of the columns seen here would be incorporated into the medieval gallery of the Yorkshire Museum, below the Tempest Anderson lecture hall, in 1912. On the right can be seen some of the unique finds discovered in the ruined abbey.

The area controlled by the society continued to grow during the Victorian period until those parts of the monastic precinct which were still open ground, along the river and up to its western boundary wall, were acquired.

Links to Related Material

- The Yorkshire Museum, by William Wilkins

- The Interior of the Yorkshire Museum, by William Wilkins

- The Observatory

- Museum Lodge

- Museum Gardens, York

- The Conservation of St Mary's Abbey's Ruins in the Yorkshire Museum Grounds

Bibliography

Boylan, Patrick. “The 200th anniversary of the discovery and first publication of the Kirkdale Cave fossil hyaena den, near Kirkbymoorside, North Yorkshire.” In Yorkshire Geological Society Circular 636, Jan-Mar 2022: 19-26. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1d9a3MbRBOBwKDyWqauwtivuvDO_OU6I4/view

Buckland, William. Reliquiae Diluvianae.... London: John Murray, 1823. Internet Archive. From a copy in the Wellcome Library. Web. 24 August 2023.

Hogarth, Peter. "Two Hundred Years Ago...." Yorkshire Philosophical Society. Web. 24 August 2023.

Hogarth, Peter J. and Ewan W. Anderson. “The most fortunate situation …” The Story of York’s Museum Gardens. York: The Yorkshire Philosophical Society, 2018.

Hume, Abraham. The Learned Societies and Printing Clubs of the Unite Kingdowm: being an account of their respective origin, history, objects and constitution.... London: G. Willis, 1853. Internet Archive. From a copy in Cornell Univeristy Library. Web. 24 August 2023.

Knight, R. and D. Hawley. “Kirkdale Cave and the Birth of the YPS.” YPSAR (York Philosophical Society Annual Record) for the Year 2021. 2022: 46-50.

YPSAR: a link to the early YPS Annual Reports: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/148582#/summary.

Created 23 August 2023

Last modified 2 September 2023