Church of St Remigius, Long Clawson, Leicestershire. Victorian restoration, completed in 1893, by R.J. & J. Goodacre of Leicester. The Grade II* listed building is on Church Lane, Long Clawson. Photographs and scans by the author, reproduced here by kind permission.

Commentary

John Betjeman's parody of the hymn, "The Church's One Foundation" (Hymns Ancient & Modern New Standard, no. 70), starting "The Church’s Restoration," gives us his mid-century reflection on what the Victorians did to our parish churches. It starts with what the poet obviously saw as the desecration of the woodwork:

The Church’s Restoration

In eighteen-eighty-three

Has left for contemplation

Not what there used to be.

How well the ancient woodwork

Looks round the Rect’ry hall,

Memorial of the good work

Of him who plann’d it all.

He who took down the pew-ends

And sold them anywhere

But kindly spared a few ends

Work’d up into a chair.

O worthy persecution

Of dust! O hue divine!

O cheerful substitution,

Thou varnished pitch-pine! .....

Yet should Betjeman not have reflected on what the Victorians did for our parish churches? St Remigius’s Church at Long Clawson is a case in point. It started as a single cell Norman church built around 1088 by the lord of the manor. About 100 years later, a plan was dreamed up for a cruciform church with a central tower, nave and transepts, the Norman church becoming the chancel. All this was completed, plus a chantry chapel in the angle of the chancel and north transept. By say 1450 the nave roof had been taken down and a clerestory added. North and south porches were added but then came not only the Reformation but also the extinction of the family who were lords of the manor. From then on, as with so many parish churches, three centuries of gentle decline ensued. The Georgian churchwardens did their bit of make-do and mend, but by the 1880s the condition was parlous. Window tracery had fallen out, the transept and chancel roofs had been taken down and the spaces covered with low-pitched lead roofs exposing the tower crossing arches to the elements, and so on.

The interior prior to restoration, with the old box pews.

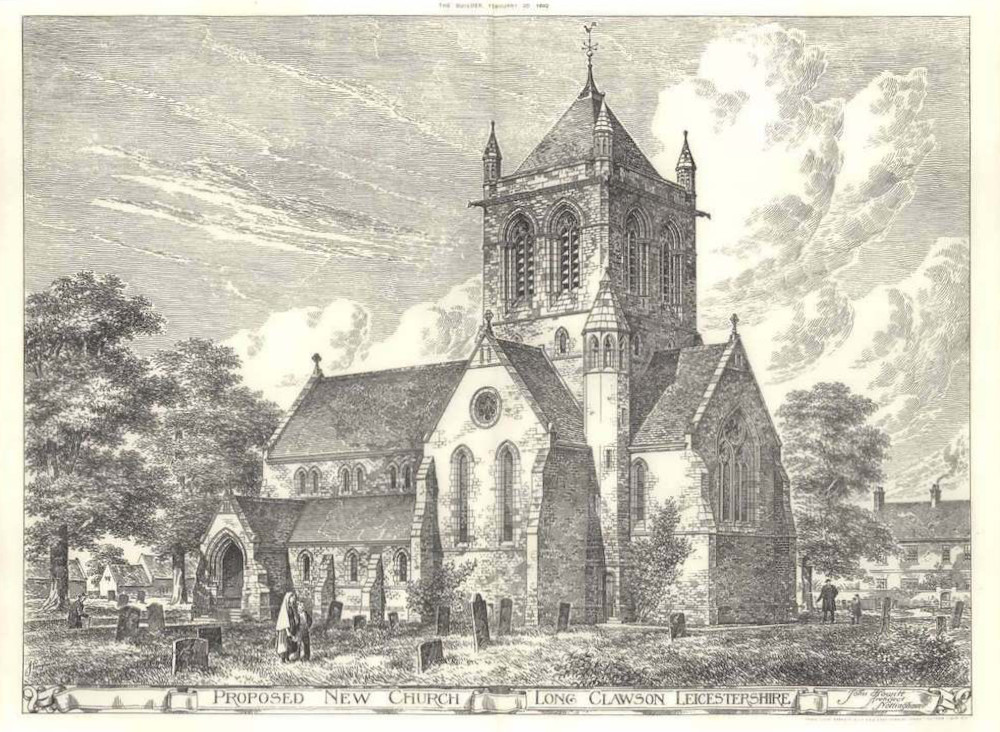

What then did the Victorians do? In 1885 Thomas Mitchell, vicar, patron and poet died after 37 years in post. He left the advowson to his daughters, one of whom was married to Edward Newcome Elborne, a Nottingham solicitor, who no doubt had a hand in presenting subsequent vicars. He teamed up with his second choice, a Mr Russell, in 1890, to obtain a bill of quantities, specification and a faculty to tear down the church and to build a French Gothic replacement with lancet windows, high roofs and no clerestory, a somewhat lumpen design by John Howitt FRIBA of Nottingham, several of whose Grade II listed warehouses and shop terraces survive in that city.

The proposed new church (never built).

But then the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings intervened, much as the Victorian Society might today [see in list of societies]: Thackeray Turner of the society wrote to the vicar and churchwardens on 18 June 1891, saying, “I who have seen the church have no hesitation in saying that the building possesses qualities of beauty which no modern church would possess…. From a religious point of view the solemnising effect of such an ancient building is of untold value.” The vicar’s committee resolved to ignore him, but others, including Mary Elizabeth Mitchell, widow of the much-loved previous vicar, agreed with Mr Turner, who even offered to fund a second architectural opinion. Thus R.J. & J. Goodacre of Leicester were appointed as architects for a restoration in the alternative. An estimate was obtained from Pendleton & Bambury, stonemasons of Leicester, in July 1892 after which the Bishop of Peterborough (then Clawson’s Diocesan) promptly wrote to the vicar advising restoration rather than rebuilding. The work was largely funded by Dr John Moore Swain MRCS, the village doctor, at a cost in today’s money of about £2million. The church was reopened in 1893, and the vicar resigned soon after. So the Victorians saw a problem, negotiated the best way to proceed, and solved the problem in just three years, exhibiting a confident can-do mentality so often missing from project management today.

Right: Vestry door, with Moore Swain's label-stops. Left two: Closer view of the label-stops.

The restoration included an 80% rebuild of the chancel, and 100% rebuild of the transepts and chantry chapel, the latter becoming the vestry. The north aisle roof was replaced, and the north arcade of the nave was dismantled and rebuilt with new clerestory windows above, and the west end of the nave and aisles were also rebuilt, retaining the window tracery. Failed corner buttresses were enlarged and intermediate buttresses added. Inside, the west gallery, the Georgian box pews, the three-decker pulpit and the low-slung ringing chamber over it were taken out, and in a nod to Tractarian views, the floor levels which had been lowest in the chancel, rising towards the nave, were reversed, lifting the Georgian stone altar by maybe three feet. And yes, there was a plethora of varnished pitch pine to seat the congregation, a bit of carved oak for the vicar, and encaustic tiling (another typically Victorian addition mentioned by Betjeman in his poem) in the sanctuary. Inside, the Georgian box pews, the three-decker pulpit and the low-slung ringing chamber over it were taken out, and in a nod to Tractarian views, the floor levels which had been lowest in the chancel, rising towards the nave, were reversed, lifting the Georgian stone altar by maybe three feet. And yes, there was a plethora of varnished pitch pine to seat the congregation, a bit of carved oak for the vicar, and encaustic tiling (another thing that Betjeman mentions in his poem) in the sanctuary.

Looking along the nave to the raised choir.

No more structural work was done than necessary. The nave roof was propped while two of its four supporting walls were rebuilt; the lead roofing to the nave, tower and south aisle, already then 150 years old is still serving now, and, albeit that the sagging porch roofs were marked for replacement in the specification, one remains unamended, the shape of a skateboard ramp. Mr Turner had observed that “the whole of the north arcade seems to have moved westward… the movement… is very marked in the western column and the cap of this column has broken in half….” Goodacres the architects noted that the “wrought stonework is mostly in good condition and required to be carefully taken down and marked and replaced in the same position.” The broken abacus could not be saved, and a new octagonal one was spliced almost seamlessly onto the cushion below. Two new archways were constructed to support the transept roofs over their abutment with the end of the aisles, with beautifully flowing and individualised corbels all carved in Corsham stone. The quality of the fine masonry is superb.

Left to right: (a) Arch to north transept. (b) One of the beautifully carved corbels, with oak leaves and acorns. (c) Spliced abacus.

Was it a win for the SPAB? Not by today’s standards. What Goodacres did was to obliterate part of the history of the building, its post-Reformation decline. If the project were taking place today and got beyond the question of whether merely to repair what was then standing, there would be accusations of pastiche about the chancel and transept design, and proposals for thermally efficient cedar-clad box-like carbuncles instead. Still, the parish remains hugely grateful to Dr Swain and his Victorian vision.

A particularly characterful "big beast" corbel.

However, it is not stuck in his era. Despite the fine stone-carving — including the quirky corbel shown on the left here — he left the interior dull, with crowded pews, a dominant pulpit, buff plaster walls, uninspired fenestration and obscure-glazed windows reminiscent of boarding school lavatories. Since his time about half the pews have been taken out creating more ambient space, the walls have been whitewashed, a Lady Chapel created in one transept with a life-sized pre-Raphaelite painting of Our Lady and Child by A. S. Coke, and clear glass put in eight windows and stained glass put in several more windows including top quality twenty-first century work by Pippa Blackall.

Later Artwork

Left to right: (a) Lady Chapel with A.S. Coke's Our Lady and Child. (b) Baptism window. (c) Creation window.

The result is a living church which retains something of its medieval past (including a stone effigy of a knight from the late thirteenth century), bolstered up by Victorian architects, and made welcoming by its present clergy for a new generation of worshippers.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Church of St Remigius, Church Lane. Historic England. Web. 1 July 2025.

Leics & Rutland Records Office DE 2300/39/1 and DE2300/43.

Created 1 July 2025