The following excerpt from J. W. Mackail's early biography of Morris explains how the Society came about and gives almost the full text of the "Manifesto" printed in the Athenaeum of 23 June 1877 (issue no. 2591, p. 807), there headed "Restoration" and prefaced by the words, "A society coming before the public with such a name as that above written must needs explain how, and why, it proposes to protect those ancient buildings which, to most people doubtless, seem to have so many and such excellent protectors. This, then, is the explanation we offer. No doubt...." There is also an additional short paragraph in the manifesto: "Thus, and thus only, shall we escape the reproach of our learning being turned into a snare to us; thus, and thus only can we protect our ancient buildings, and hand them down instructive and venerable tothose that come after us." [Transcribed, formatted, illustrated and linked by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on all the images to enlarge them and for more information about them.]

t the beginning of March, 1877, an account of the proposed

restoration of the splendid Abbey church at Tewkesbury

roused him to take practical steps. Mr. F. G. Stephens

had for some years been upholding the cause of ancient

buildings in the

Morris's Letter to the Athenaeum (5 March 1877)

Portrait of William Morris in 1870, by G.F. Watts.

©National Portrait Gallery.

"My eye just now caught the word 'restoration' in the morning paper, and, on looking closer, I saw that this time it is nothing less than the Minster of Tewkesbury that is to be destroyed by Sir Gilbert Scott. Is it [340/341] altogether too late to do something to save it, it and whatever else of beautiful and historical is still left us on the sites of the ancient buildings we were once so famous for? Would it not be of some use once for all, and with the least delay possible, to set on foot an association for the purpose of watching over and protecting these relics, which, scanty as they are now become, are still wonderful treasures, all the more priceless in this age of the world, when the newly-invented study of living history is the chief joy of so many of our lives?

Your paper has so steadily and courageously opposed itself to these acts of barbarism which the modern architect, parson, and squire call 'restoration,' that it would be waste of words to enlarge here on the ruin that has been wrought by their hands ; but, for the saving of what is left, I think I may write a word of encouragement, and say that you by no means stand alone in the matter, and that there are many thoughtful people who would be glad to sacrifice time, money, and comfort in defence of those ancient monuments : besides, though I admit that the architects are, with very few exceptions, hopeless, because interest, habit, and ignorance bind them, and that the clergy are hopeless, because their order, habit, and an ignorance yet grosser, bind them; still there must be many people whose ignorance is accidental rather than inveterate, whose good sense could surely be touched if it were clearly put to them that they were destroying what they, or, more surely still, their sons and sons' sons, would one day fervently long for, and which no wealth or energy could ever buy again for them.

"What I wish for, therefore, is that an association should be set on foot to keep a watch on old monuments, to protest against all 'restoration' that means more than keeping out wind and weather, and, by all [341/42] means, literary and other, to awaken a feeling that our ancient buildings are not mere ecclesiastical toys, but sacred monuments of the nation's growth and hope."

The train caught fire. A fortnight after this letter appeared, the Athenaeum announced that his proposal was likely to take effect, and within another fortnight the Society for Protection of Ancient Buildings had been constituted and had held its first meeting, Morris acting as secretary. The eminent men in many walks of life who at once joined it were sufficient to protect it from either contempt or ridicule; and if it has not stayed destruction, it has at all events saved much that would otherwise have been lost, and has had an immense though quiet influence in raising the standard of morality on the subject of ancient buildings throughout England. Architects and owners alike now take a wholly new and wholly beneficial sense of their responsibility. The principles of the Society are given by Morris with unsurpassed lucidity and force in the statement issued by it on its foundation.

"Within the last fifty years a new interest, almost like another sense, has arisen in these ancient monuments of art; and they have become the subject of one of the most interesting of studies, and of an enthusiasm, religious, historical, artistic, which is one of the undoubted gains of our time ; yet we think that if the present treatment of them be continued, our descendants will find them useless for study and chilling to enthusiasm. We think that those last fifty years of knowledge and attention have done more for their destruction than all the foregoing centuries of revolution, violence, and contempt.

"For architecture, long decaying, died out, as a popular art at least, just as the knowledge of mediaeval art was born. So that the civilized world of the nine-[342/43] teenth century has no style of its own amidst its wide knowledge of the styles of other centuries. From this lack and this gain arose in men's minds the strange idea of the Restoration of ancient buildings; and a strange and most fatal idea, which by its very name implies that it is possible to strip from a building this, that, and the other part of its history of its life, that is and then to stay the hand at some arbitrary point, and leave it still historical, living, and even as it once was.

"In early times this kind of forgery was impossible, because knowledge failed the builders, or perhaps be- cause instinct held them back. If repairs were needed, if ambition or piety pricked on to change, that change was of necessity wrought in the unmistakable fashion of the time; a church of the eleventh century might be added to or altered in the twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth, or even the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; but every change, whatever history it destroyed, left history in the gap, and was alive with the spirit of the deeds done amidst its fashioning. The result of all this was often a building in which the many changes, though harsh and visible enough, were by their very contrast interesting and instructive, and could by no possibility mislead. But those who make the changes wrought in our day under the name of Restoration, while professing to bring back a building to the best time of its history, have no guide but each his own individual whim to point out to them what is admirable and what contemptible : while the very nature of their task compels them to destroy something, and to supply the gap by imagining what the earlier builders should or might have done. Moreover, in the course of this double process of destruction and addition, the whole surface of the building is necessarily tampered with; so that the appearance of antiquity is taken away from [343/44]such old parts of the fabric as are left, and there is no laying to rest in the spectator the suspicion of what may have been lost; and in short, a feeble and lifeless forgery is the final result of all the wasted labour.

"Of all the Restorations yet undertaken the worst have meant the reckless stripping a building of some of its most interesting material features; while the best have their exact analogy in the Restoration of an old picture, where the partly perished work of the ancient craftsmaster has been made neat and smooth by the tricky hand of some unoriginal and thoughtless hack of to-day. If, for the rest, it be asked us to specify what kind or amount of art, style, or other interest in a building, makes it worth protecting, we answer, Anything which can be looked on as artistic, picturesque, historical, antique, or substantial : any work, in short, over which educated artistic people would think it worth while to argue at all.

"It is for all these buildings, therefore, of all times and styles, that we plead, and call upon those who have to deal with them, to put Protection in the place of Restoration, to stave off decay by daily care, to prop a perilous wall or mend a leaky roof by such means as are obviously meant for support or covering, and show no pretence of other art, and otherwise to resist all tampering with either the fabric or ornament of the building as it stands; if it has become inconvenient for its present use, to raise another building rather than alter or enlarge the old one; in fine, to treat our ancient buildings as monuments of a bygone art, created by bygone manners, that modern art cannot meddle with without destroying."

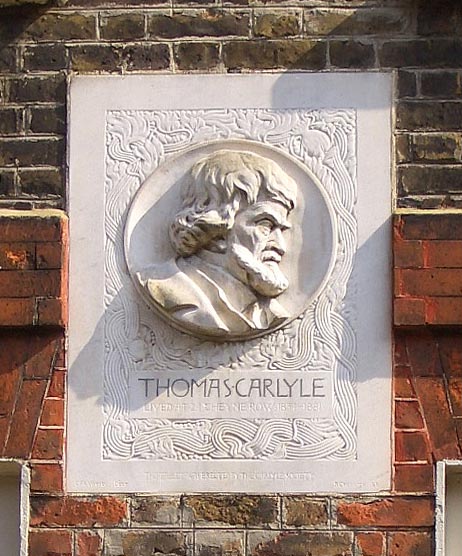

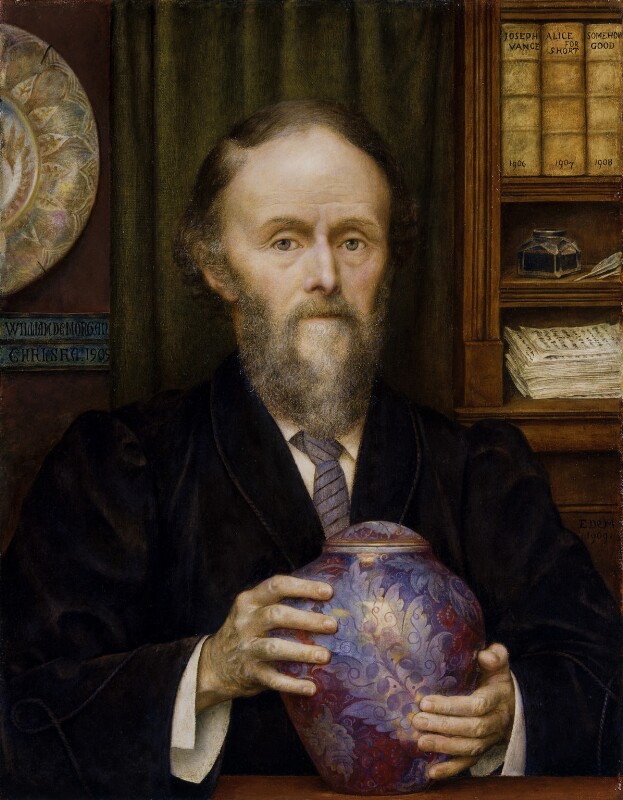

Involvement of Carlyle and William De Morgan

Left: Benjamin Creswick's portrait plaque of Carlyle on his house on Cheyne Row, Right: Portrait of William De Morgan, by his wife Evelyn, 1909. ©National Portrait Gallery.

Among the celebrated names whom the newly-founded Society was able to announce as members was that of Carlyle. The story of how he was induced to join it is highly characteristic: I owe it to Mr. William De Morgan, [344/45] through whom, as a neighbour and friend, living in Cheyne Row a few doors off, Carlyle was approached.

"I sent the prospectus to Carlyle," Mr. De Morgan tells me, "through his niece Miss Aitken, and afterwards called by appointment to elucidate further. The philosopher didn't seem in the mood to join anything in fad it seemed to me that the application was going to be fruitless. But fortunately Sir James Stephen was there when I called, and Carlyle passed me on to him with the suggestion that I had better make him a convert first. However, Sir James declined to be converted, on the ground that the owners or guardians of ancient buildings had more interest than any one else in preserving them, and would do it, and so forth. I replied with a case to the contrary, that of Wren's churches and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. This brought Carlyle out with a panegyric of Wren, who was, he said, a really great man, 'of extraordinary patience with fools,' and he glared round at the company reproachfully. However, he promised to think it over, chiefly, I think, because Sir James Stephen had rather implied that the Society's object was not worth thinking over. He added one or two severe comments on the contents of space.

"I heard from his niece next day that he was wavering, and that a letter from Morris might have a good effect. I asked for one, and received the following:<>/p>

Horrington House,

4 April 3

My dear De Morgan,

I should be sorry indeed to force Mr. Carlyle's inclinations on the matter in question, but if you are seeing him I think you might point out to him that it is not only artists or students of art that we are appealing to, but thoughtful people in general. For the rest [346/47] it seems to me not so much a question whether we are to have old buildings or not, as whether they are to be old or sham old : at the lowest I want to make people see that it would surely be better to wait while architecture and the arts in general are in their present experimental condition before doing what can never be undone, and may at least be ruinous to what it intends to preserve.

Yours very truly,

WILLIAM MORRIS

Next day," Mr. De Morgan goes on, " I received from Miss Aitken a letter from Carlyle to the Society, accepting membership. It made special allusion to Wren, and spoke of his City churches as c marvellous works, the like of which we shall never see again/ or nearly that. Morris had to read this at the first public meeting you may imagine that he didn't relish it, and one heard it in the way he read it I fancy he added mentally, 'And a good job too!'

Furtherance of the Project

Morris's prejudice against the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was indeed carried to a pitch that amounted to pure unreasonableness: and in the work of Wren and his successors he steadily declined to acknowledge either fitness, or dignity, or elegance.

The rather lumbering title of the Society was at an early date replaced for familiar usage by the more terse and expressive name of the Anti-Scrape, a word of Morris's own invention. Two months after its formation he writes to a friend: "By the way you have not yet joined our Anti-Scrape Society: I will send you the papers of it: the subscription is only 10/6, and may save you something if people ask for subscriptions to restorations by enabling you to say, 'I am sorry, but be damned — look here.'"

Related Material

- On Joining the SPAB

- (Offsite) The SPAB website

Bibliography

Mackail, John William. The Life of William Morris, Vol. I. London, New York & Bombay: Longmans, Green and Co., 1899. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 18 April 2021.

Created 18 April 2021