Immediately to the east of the Chelsea Hospital lay the once-famous Ranelagh Gardens, the fashionable resort of beaux and fair ladies from 1742 to 1803 built on the grounds of Ranelagh House by the Earl of that name, who had been the military Paymaster for James II. A sharp and unscrupulous businessman who amassed a fortune while in office, Ranelagh obtained a grant of the land from the Royal Chelsea Hospital, on which he built a great house and laid out an ornate garden, with "plots, borders, and walks . . . curiously kept, and elegantly designed" (London Parks and Gardens, 1907). His heirs later leased part of the property to a series of developers who created the fashionable amusement park, which had been closed for nearly four decades when William Harrison Ainsworth used them as one of the settings for his 1842 historical novel The Miser’s Daughter. — Philip V. Allingham. —

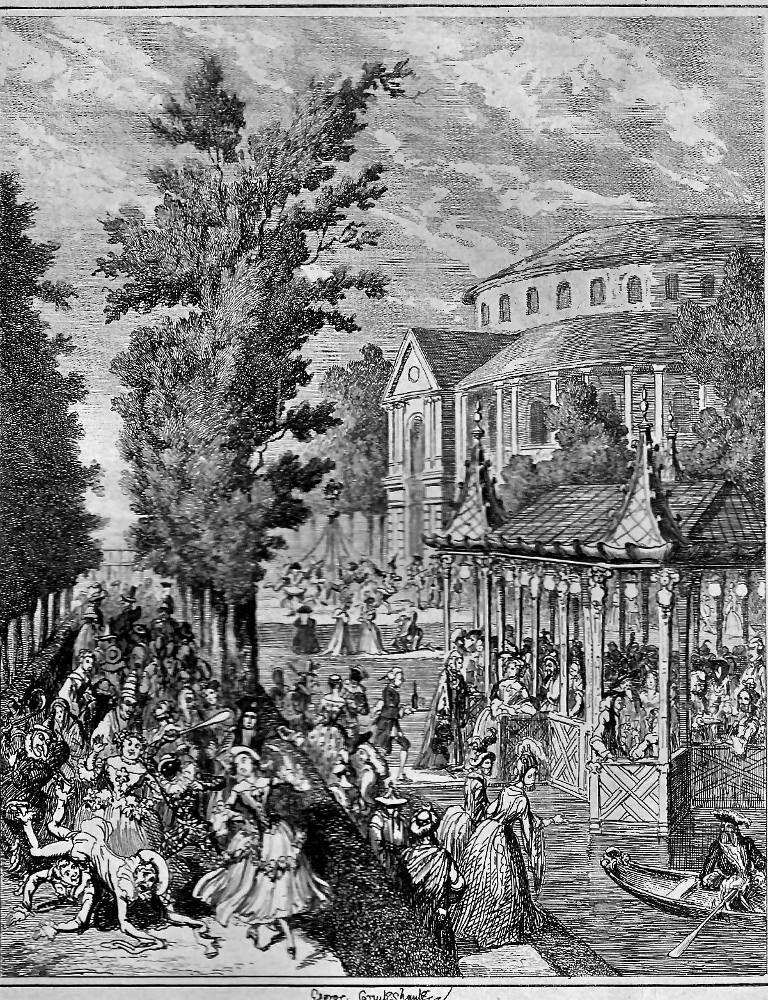

The Pleasure Gardens at Ranelagh, Chelsea, as envisaged byGeorge Cruikshank [June 1842].Cruikshank probably modelled his book illustrations after a hand-coloured engraving by Charles Grignion’s engraving of a work by Antonio Canaletto, dating from the 1750s.

And now before entering Ranelagh, it may be proper to offer a word as to its history. Alas! for the changes and caprices of fashion! This charming place of entertainment, the delight of our grandfathers and grandmothers, the boast of the metropolis, the envy of foreigners, the renowned in song and story, the paradise of hoops and wigs, is vanished, — numbered with the things that were! — and, we fear, there is little hope of its revival. Ranelagh, it is well known, derived its designation from a nobleman of the same name, by whom the house was erected, and the gardens, esteemed the most beautiful in the kingdom, originally laid out. Its situation adjoined the Royal Hospital at Chelsea; and the date of its erection was 1690-1. Ranelagh House, on the death of the earl, in 1712, passed into the possession of his daughter, Lady Catherine Jones; but was let, about twenty years afterwards, to two eminent builders, who relet it to Lacy, afterwards patentee of Drury Lane Theatre, and commonly called Gentleman Lacy, by whom it was taken with the intention of giving concerts and breakfasts within it, on a scale far superior, in point of splendour and attraction, to any that had been hitherto attempted.

In 1741, the premises were sold by Lacy to Messrs. Crispe and Meyonnet for 4000£., and the rotunda was erected in the same year by subscription. From this date, the true history of Ranelagh may be said to commence. It at once burst into fashion, and its entertainments being attended by persons of the first quality, crowds flocked in their train. Shortly after its opening, Mr. Crispe became the sole lessee; and in spite of the brilliant success of the enterprise, shared the fate of most lessees of places of public amusement, being declared bankrupt in 1744. The property was then divided into thirty shares, and so continued until Ranelagh was closed.

The earliest entertainments of Ranelagh were morning concerts, consisting chiefly of oratorios, produced under the direction of Michael Festing, the leader of the band; but evening concerts were speedily introduced, the latter, it may be mentioned, to shew the difference of former fashionable hours from the present, commencing at half-past five, and concluding at nine. Thus it began, but towards its close, the gayest visitors to Ranelagh went at midnight, just as the concerts were finishing, and remained there till three or four in the morning. In 1754, the fashionable world were drawn to Ranelagh by a series of amusements called Comus's Court; and notwithstanding their somewhat questionable title, the revels were conducted with great propriety and decorum. A procession which was introduced was managed with great effect, and several mock Italian duets were sung with remarkable spirit.

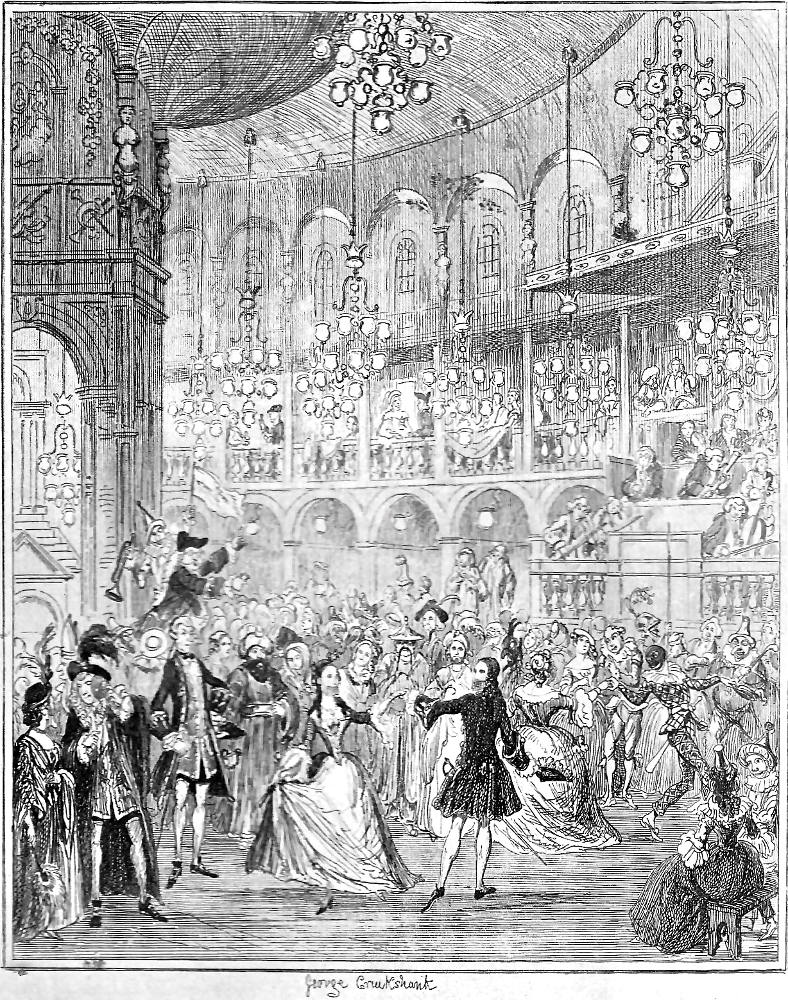

Almost to its close, Ranelagh retained its character of being the finest place of public entertainment in Europe, and to the last the rotunda was the wonder and delight of every beholder. The coup-d'oeil of the interior of this structure was extraordinarily striking, and impressed all who beheld it for the first time with surprise. It was circular in form, and exactly one hundred and fifty feet in diameter. Round the lower part of the building ran a beautiful arcade, the intervals between each arch being filled up by alcoves. Over this was a gallery with a balustrade, having entrances from the exterior, and forming a sort of upper boxes. Above the gallery was a range of round-headed windows, between each of which was a carved figure supporting the roof, and forming the terminus of the column beneath. At first, the orchestra was placed in the centre of the amphitheatre, but being found exceedingly inconvenient, as well as destructive of the symmetry of the building in that situation, it was removed to the side. It contained a stage capable of accommodating thirty or forty chorus-singers. The original site of the orchestra was occupied by a large chimney, having four faces enclosed in a beautifully-proportioned hollow, hexagonal column, with arched openings at the sides, and a balustrade at the base. Richly moulded, and otherwise ornamented with appropriate designs, this enormous column had a charming effect, and gave a peculiar character to the whole amphitheatre. A double range of large chandeliers descended from the ceiling; others were placed within the column above mentioned, and every alcove had its lamp. When all these chandeliers and lamps were lighted, the effect was wonderfully brilliant.

The external diameter of the rotunda was one hundred and eighty-five feet. It was surrounded on the outside by an arcade similar to that within, above which ran a gallery, with a roof supported by pillars, and defended by a balustrade. The main entrance was a handsome piece of architecture, with a wide, round arched gate in the centre, and a lesser entrance at either side. On the left of the rotunda stood the Earl of Ranelagh's old mansion, a structure of some magnitude, but with little pretension to beauty, being built in the formal Dutch taste of the time of William of Orange. On the right, opposite the mansion, was a magnificent conservatory, with great pots of aloes in front. In a line with the conservatory, and the side entrance of the rotunda, stretched out a long and beautiful canal, in the midst of which stood a Chinese fishing-temple, approached by a bridge. On either side of the canal were broad gravel walks, and alleys shaded by lines of trees, and separated by trimly-clipped hedges. The gardens were exquisitely arranged with groves, bowers, statues, temples, wildernesses, and shady retreats. [The Miser’s Daughter, Chapter VIII, pp. 171-73]

Related Materials

- The Development of Leisure in Britain, 1700-1850

- The Development of Pantomime, 1692-1761

- Music, Theater, and Popular Entertainment in Victorian Britain (sitemap)

- London Recreations from Dickens's Sketches by Boz (1839)

- Vauxhall Gardens by Day (1839)

- Greenwich Fair (1839)

- Mr. Lambkin goes to a Masquerade as Don Giovanni (1844)

References

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. With 20 illustrations by George Cruikshank. First published in 3 volumes by Cunningham and Mortimer, London, 1842. London, Glasgow, and New York: George Routledge, 1892.

"Ranelagh Gardens." Chapter 12: "Historical Gardens," in London Parks and Gardens, 1907. Online version available from Garden Visit.com — The Garden Guide. Web. 18 June 2018.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Last modified 22 June 2018