he two original illustrators of Great Expectations were Marcus Stone (1862) in Britain, and

John McLenan (1860-61) in America. They treat the major characters of the novels very differently. Not the

smallest difference is their contrasting numbers: Stone's eight to McLenan's forty. But a

detailed discussion of several of Stone's full-page wood-engravings which parallel in

their depiction of Miss Havisham some of those in McLenan's series in

Harper's

Weekly (November 1860 through July 1861) is still instructive.

he two original illustrators of Great Expectations were Marcus Stone (1862) in Britain, and

John McLenan (1860-61) in America. They treat the major characters of the novels very differently. Not the

smallest difference is their contrasting numbers: Stone's eight to McLenan's forty. But a

detailed discussion of several of Stone's full-page wood-engravings which parallel in

their depiction of Miss Havisham some of those in McLenan's series in

Harper's

Weekly (November 1860 through July 1861) is still instructive.

Introducing Miss Havisham

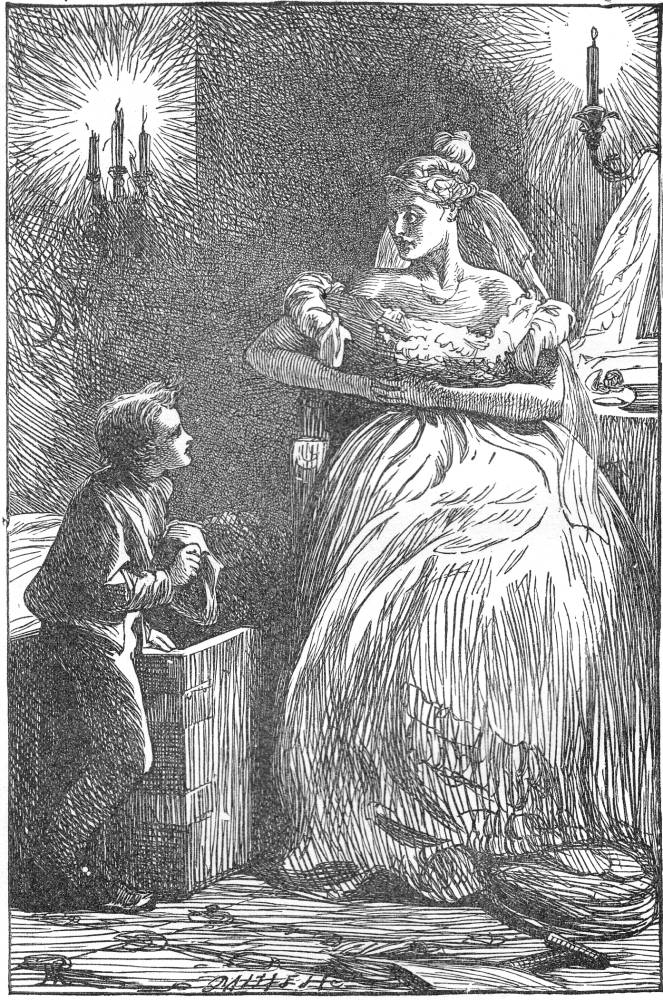

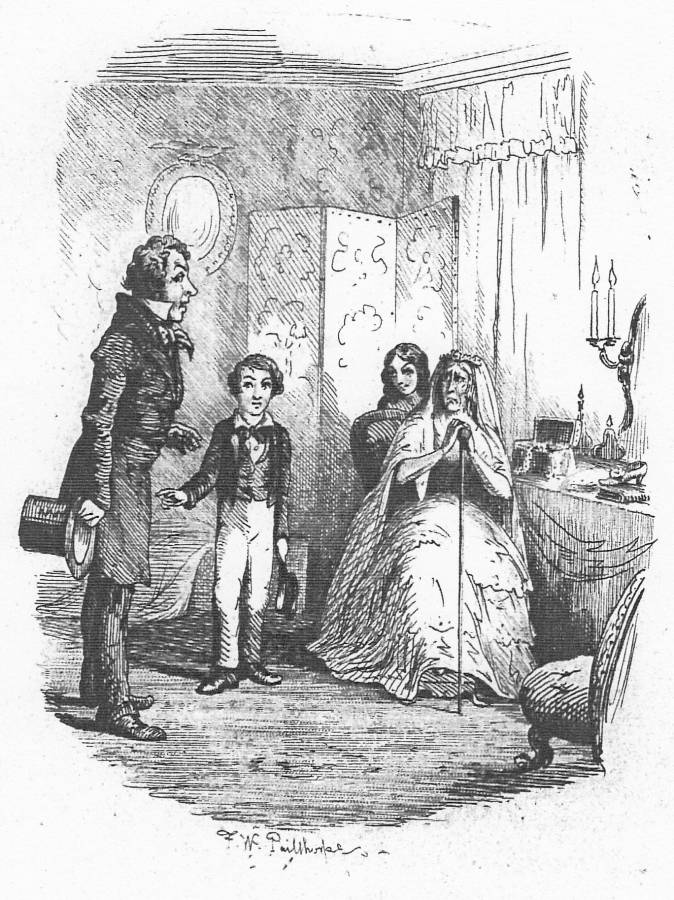

Marcus Stone's evocative illustration of the aging heiress as a young and beautiful fairytale godmother or princess: Pip Waits on Miss Havisham (1862).

Prominent in both the original illustrated edition and the subsequent British editions of 1862 through 1910, Miss Havisham is the lonely doyenne of Satis House, an arch manipulator. Stone's initial treatment is anything but realistic; in fact, his wood-engraving, Pip Waits on Miss Havisham, is almost a comment on the psychology of the narrator. The mature Pip, looking back upon his initial meeting with her inside the candle-lit house, sees her in his mind's eye as a Fairy Godmother, and not a wizened crone in a desiccated wedding-dress. She is beautiful, enthralling, and aloof. In contradiction to the letter-press, Stone depicts her as youthful and attractive. Commanding in presence, she is lit by candelabra, enthroned as it were before her humble supplicant, the village blacksmith's boy. Cap in hand, Pip slightly bends at the knees, while the large-eyed, imperious woman with the elaborately arranged blonde hair and bare-shouldered, voluminous wedding dress (apparently no worse for a number of years of wear), her mirror just disappearing off the right-hand margin.

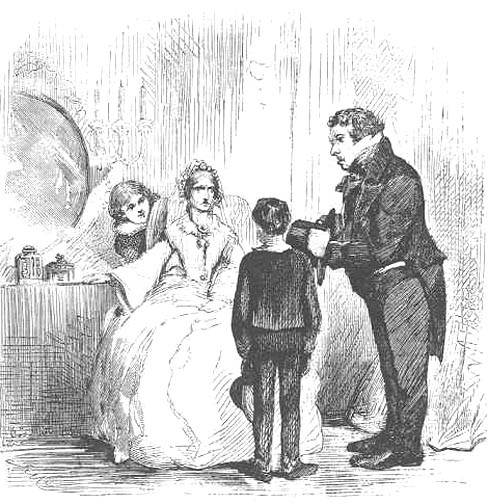

McLenan's introduction of Miss Havisham in her curtained boudoir: "Who is it?" said the lady at the table. "Pip, Ma'am." (15 December 1860).

McLean's larger-scale illustrations for Harper's Weekly, reproduced in the T. B. Peterson single-volume edition of 1861, show Miss Havisham in a far more realistic light. The American illustrator's three early Miss Havisham plates are on pages 49, 63, and 70 in this edition. Instead of the glowing image from Pip's memory, McLenan depicts a despondent, introverted, somewhat elderly and angular bride in front of her mirror. McLenan has responded more accurately (if less delightfully) to the letter-press.

As we turn page 48 in the late 1861 Philadelphia volume we encounter the vignetted illustration "Who is it?" said the lady at the table. "Pip, ma'am." — Page 49 before we actually find the same moment in the letter-press. Whereas Stone had filled the frame with the enchanting fairy godmother, McLenan sets his crone in the midst of her furnishings and belongings. As in the text, open trunks (left and right) covered with clothing frame the scene, and an inward-gazing Miss Havisham in an attitude of despondency, hand supporting her head, sits before an oval mirror which has four candlelabra attached. Faithful to his copy, the illustrator has included such details as the white shoe on the dressing table (Pip indicates that he can see the other white shoe on her foot, which McLenan conceals beneath her skirts). Although neither artist has depicted the faded flowers mentioned in the narrative, the watch and chain are evident just to the right of Miss Havisham's left elbow in Stone's version, important symbols of her rejection of the passage of time. Another interesting if minor detail which varies in the two plates is Pip's hat: in Stone's plate, it is a cloth cap such as was worn by the British working class, whereas in McLenan's plate it is a brimmed felt hat, which the American artist supplied from his own experience and period. Yet another detail given in the text is Miss Havisham's jewellery. Stone passes over this, despite the glimmering of the four powerful candles in his illustration. But the American artist does depict the jewels, seen by the faint light of the four tapers in the room. Attention to such minutiae is not always an advantage, however: the English illustration is dramatic and powerful because Stone has reduced the scene to its essentials, and placed the contrasting figures in close proximity, balancing the difference in their heights by placing three candles above Pip and creating a sense of the numinous that the American plate entirely lacks. The overall effect of McLenan's composition is awkward and stilted in comparison.

Stone's and McLenan's later Illustrations of Miss Havisham

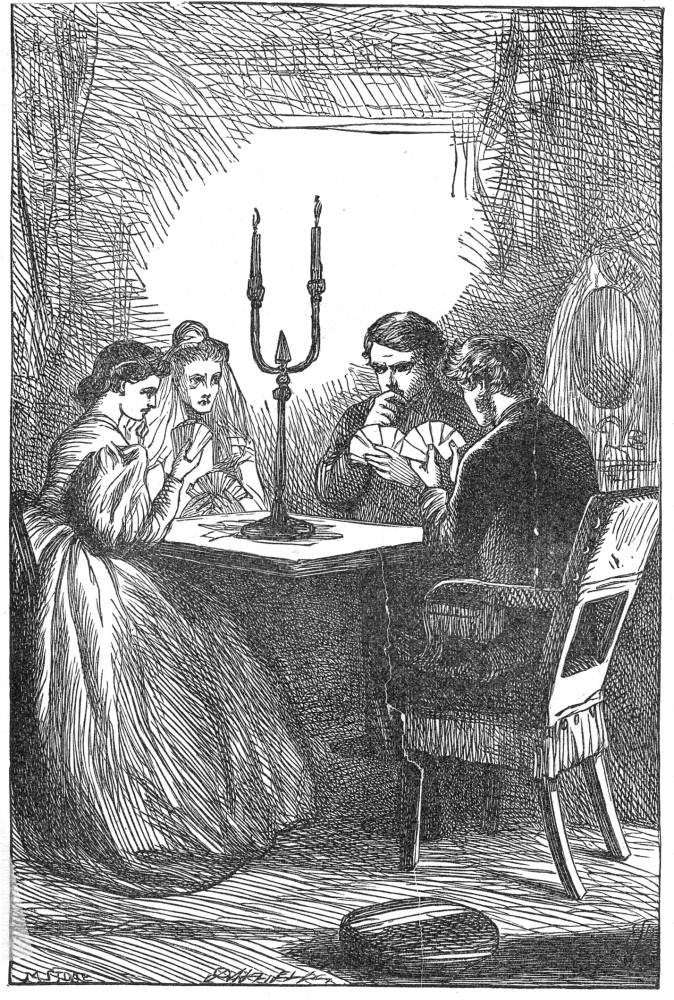

Marcus Stone's far more realistic assessment of a wily manipulator, an elderly heiress keeping her cards close: A Rubber at Miss Havisham's (1862).

Of Stone's eight plates, only one other besides Pip Waits on Miss Havisham features this figure. He is more interested in graphing Pip's journey from childhood to maturity, indicating that the Bildungsroman aspect of the novel was uppermost in the British illustrator's mind. This second and last one is A Rubber at Miss Havisham's. Here, the desiccated figure serves as a chronometer for the mature Pip, Herbert, and Estella: one has the distinct sense that she has aged and shrunk considerably since Pip first encountered her in Stone's narrative-pictorial sequence. Although she is still associated in this later plate with lighted tapers, our view of Miss Havisham is blocked by the youthful figure of Estella, who now wields the real power over Pip.

This yielding of place is much less succinctly shown by McLenan, who continues to give Miss Havisham prominence. Of the American illustrator's thirty-four full-size plates (in other words, those reprinted in the Peterson single-volume edition after their serial appearances), four depict Miss Havisham in her boudoir (facing pages 48, 64, 70, and 204); one shows her candle in hand in a corridor (facing page 176), and the last and most sensational one depicts her ablaze in the dining-room (facing page 224). Thus, McLenan features Miss Havisham prominently in five of his plates while, for example, Magwitch occurs in five, Joe in seven, and Pip in 29. And not once is she shown in flashback as youthful, beautiful, and optimistic: for McLenan she is never the fairy godmother but the haggard, vengeful witch out of myth, legend, and fairytale.

McLenan's explanation of Miss Havisham's reclusive behaviour:"It's a great cake. "'A bride-cake. Mine!" (5 January 1861).

Miss Havisham remains a static figure in McLenan's "It's a great cake. "'A bride-cake. Mine!" — Page 63 and "Which I meantersay, Pip". — Page 70 (12 January 1861), both of which are nevertheless accurate in the details of each scene, the dining room and the boudoir — although Pip is perhaps too well dressed for a mere labouring boy and one wonders how the latter scene is lit, considering that the windows are covered but the candles above Estella are unlit. Interestingly, all three of McLenan's Havisham plates have mirrors as their central features, though none of them actually reflects anything. These "blind" mirrors may reflect the psychological blindness of Miss Havisham to her true condition; in David Lean's 1946 film, Miss Havisham is, as Regina Barreca notes, "framed next to mirrors in a number of scenes, making visual the way the spinster wishes to multiply her image through Estella" (41). However, McLenan's mirrors return no image, suggesting the sterility of lifelessness of Satis House which accords well with the static, rigid depiction of the figures, rotund Joe furnishing in his darkly clad amplitude a sharp contrast to Miss Havisham's severe whiteness, stark thinness, and pronounced angularity.

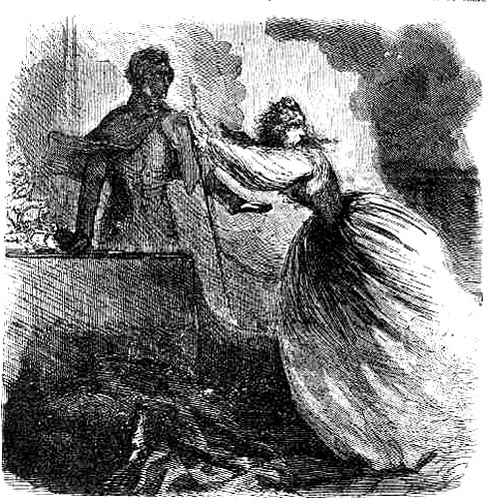

Left: McLenan's only scene of comic relief involving Miss Havisham: "Which I meantersay, Pip" (12 January 1861). Right: McLenan's sensational immolation scene, in which statue-like Pip is momentarily powerless to assist Miss Havisham: I saw her running at me, shrieking, with a whirl of fire blazing all about her (22 June 1861).

The desiccated figure who serves as a chronometer for the mature Pip, Herbert, and Estella in Stone's A Rubber at Miss Havisham's eventually becomes her own candle in McLenan's plate I saw her running at me, shrieking, with a whirl of fire blazing all about her (22 June 1861) opposite page 224 in the Peterson edition (bottom, p. 286, in Harper's). She has aged and shrunk considerably. As the smoke billows (right) and flames engulf her skirts in McLenan's plate, we are struck once again by the awkward rigidity of the figures: although Miss Havisham's look of horror is utterly convincing, her waist is not.

Again, a comparison with Stone is telling. Real bodies seem to have sat as the originals for all of Stone's plates, which show a pronounced tendency towards realistic portraiture: "Stone worked from models, and his naturalistic portrayals of characters suited the academic tastes of the times" (Cohen 204). Miss Havisham is a difficult subject to present in an entirely naturalistic way. Perhaps nowhere else in his series of plates for Great Expectations is Stone's departure from what Cohen terms the outmoded "Hogarth-Cruikshank-Browne tradition" (204) of the steel etching more evident and effective than his last of the eight illustrations, with the mature Pip and Estella in the ruined garden at Satis House. They have left Miss Havisham behind: In With Estella after all, "morning mists" have dispelled the shadows of the past and the legacy of this blighted and unfortunate character.

Miss Havisham by Other Illustrators (1867 onwards)

Left to right: (a) Miss Havisham and Estella (1867), from the Diamond Edition by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (b) F. A. Fraser's Household Edition version of Pip's presenting his benefactress to Joe for his apprenticeship: "Well, Pip, you know, . . . . you yourself see me put 'em in my 'at" (1876). (c) Frederic W. Pailthorpe's version of this same scene: I present Joe to Miss Havisham, in the Garnett Edition (1885). (d) Harry Furniss's illustration of an enthroned but desiccated heiress in a crumbling wedding-gown: Miss Havisham (1910).

Related Material

- Dickens's Great Expectations in Film and Television, 1917-2000

- Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

- Bibliography of works relevant to illustrations of Great Expectations

Various Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (2 lithographs from watercolours)

- Felix O. C. Darley (4 photogravure plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- F. A. Fraser in the Household Edition (29 wood engravings)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

- Frederic W. Pailthorpe (21 steel engravings)

- Marcus Stone (8 wood engravings)

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

Barreca, Regina. “David Lean's Great Expectations."Dickens on Screen, ed. John Glavin. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2003. Pp. 39-44.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Chapter 16, Marcus Stone." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1980. Pp. 203-209.

Davis, Paul B. "Dickens, Hogarth, and the Illustrations for Great Expectations." Dickensian 80, 3 (Autumn, 1984): 130-143.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. All the Year Round. Vols. IV and V. 1 December 1860 through 3 August 1861.

_______. ("Boz."). Great Expectations. With thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson (by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York), 1861.

_______. Great Expectations. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1862. Rpt. in The Nonesuch Dickens, Great Expectations and Hard Times. London: Nonesuch, 1937; Overlook and Worth Presses, 2005.

_______. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition.16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. XIII.

_______. Great Expectations. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. Illustrated by F. A. Fraser. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

_______. Great Expectations. The Gadshill Edition. Illustrated by Charles Green. London: Chapman and Hall, 1897-1908.

_______. Great Expectations. "With 28 Original Plates by Harry Furniss." Volume 14 of the Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

McLenan, John, illustrator. Charles Dickens's Great Expectations [the First American Edition]. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Vols. IV: 740 through V: 495 (24 November 1860-3 August 1861). Rpt. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1861.

Paroissien, David. "Hypothetical Chronology." The Companion to "Great Expectations." Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 2000. Pp. 424-434.

Created 14 November 2021