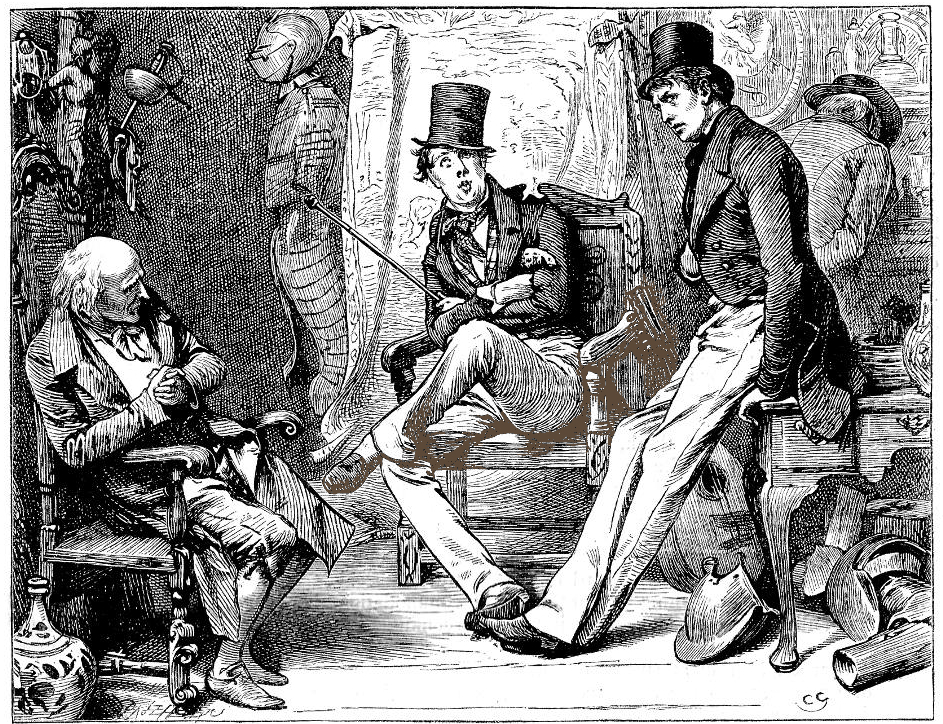

The old man sat himself down in a chair, and, with folded hands, looked sometimes at his grandson and sometimes at his strange companion — Chap. II by Charles Green. 1876. 10.7 cm high by x 13.8 cm wide. Dickens's The Old Curiosity Shop, in the British Household Edition, XII, 1.

Context of the Illustration: The indolent Mr. Swiveller in the Chair

It was perhaps not very unreasonable to suspect from what had already passed, that Mr. Swiveller was not quite recovered from the effects of the powerful sunlight to which he had made allusion; but if no such suspicion had been awakened by his speech, his wiry hair, dull eyes, and sallow face would still have been strong witnesses against him. His attire was not, as he had himself hinted, remarkable for the nicest arrangement, but was in a state of disorder which strongly induced the idea that he had gone to bed in it. It consisted of a brown body-coat with a great many brass buttons up the front and only one behind, a bright check neckerchief, a plaid waistcoat, soiled white trousers, and a very limp hat, worn with the wrong side foremost, to hide a hole in the brim. The breast of his coat was ornamented with an outside pocket from which there peeped forth the cleanest end of a very large and very ill-favoured handkerchief; his dirty wristbands were pulled on as far as possible and ostentatiously folded back over his cuffs; he displayed no gloves, and carried a yellow cane having at the top a bone hand with the semblance of a ring on its little finger and a black ball in its grasp. With all these personal advantages (to which may be added a strong savour of tobacco-smoke, and a prevailing greasiness of appearance) Mr. Swiveller leant back in his chair with his eyes fixed on the ceiling, and occasionally pitching his voice to the needful key, obliged the company with a few bars of an intensely dismal air, and then, in the middle of a note, relapsed into his former silence.

The old man sat himself down in a chair, and with folded hands, looked sometimes at his grandson and sometimes at his strange companion, as if he were utterly powerless and had no resource but to leave them to do as they pleased. The young man reclined against a table at no great distance from his friend, in apparent indifference to everything that had passed; and I — who felt the difficulty of any interference, notwithstanding that the old man had appealed to me, both by words and looks — made the best feint I could of being occupied in examining some of the goods that were disposed for sale, and paying very little attention to a person before me.

The silence was not of long duration, for Mr. Swiveller, after favouring us with several melodious assurances that his heart was in the Highlands, and that he wanted but his Arab steed as a preliminary to the achievement of great feats of valour and loyalty, removed his eyes from the ceiling and subsided into prose again. [Chapter II, 9]

Commentary: A Study in Contrasts: Affability, Insolence, and Querolousness

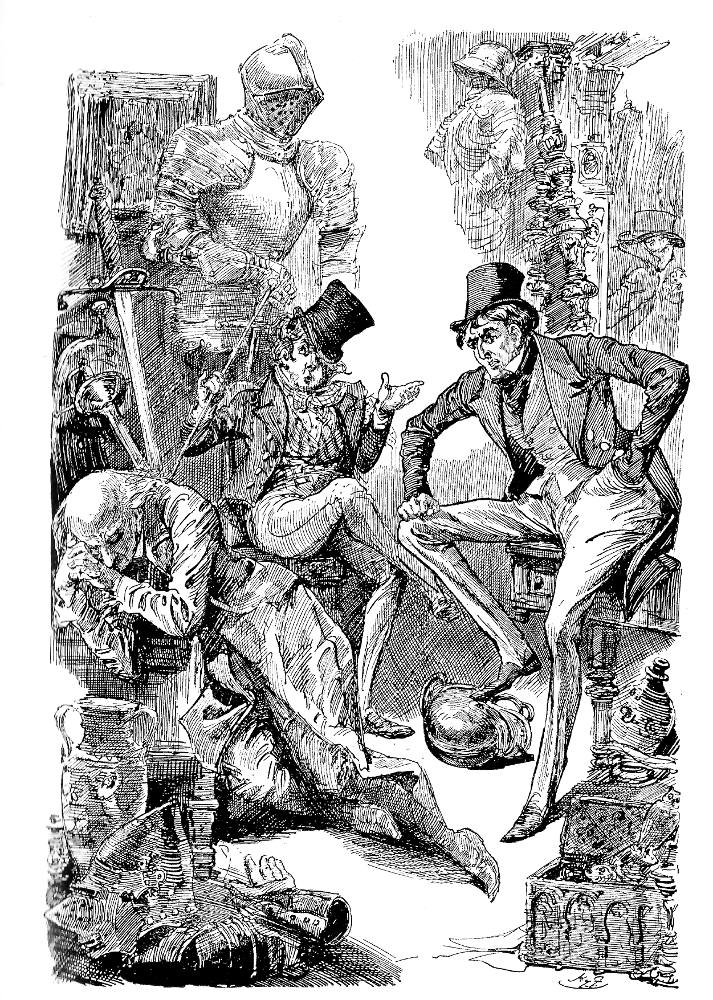

Right: Harry Furniss's study of the interview of Fred, his grandfather, and

the dissolute law clerk Dick Siveller, with the emphasis on the figures rather than on

the cluttered backdrop, in which Furniss has not placed the narrator, Master Humphrey:

Green has departed from the caricatural style of the original serial's illustrations by George Cattermole and Phiz, and the lesser members of the team of illustrators whom Dickens described as "The Clock Works." Although Green seems to be reiterating the importance of the Old Curiosity Shop as the novel's in the first three illustrations, this atmospheric interior only appears twice more as the illustrator follows Little Nell and her grandfather into the English countryside, and focusses on the figures of Dick Swiveller, the Marchioness, and particularly on the distorted figure of the villainous dwarf, Daniel Quilp.

As a customer (in fact, as the passage makes clear, Master Humphrey, the narrator) inspects an object at the back, in the foreground Grandfather Trent shrinks slightly in his armchair as the affable but somewhat addled-headed companion of grandson Fred, Dick Swiveller, tries in vain to settle himself comfortably into the chair as he sings an air from Robbie Burns. Fred, the tall, fashionably dressed young man to the right, nervously glances towards the viewer, as if the subject he is about to broach is an unpleasant one.

Frederick Trent reveals himself as Nell's older brother, scheming to get to old man's fortune. Fred mistakenly, and even obdurately believes that his grandfather has accumulated considerable wealth, which he hoards rather than gives to his grandchildren. Fred's moody truculence here prepares us for his schemes to have his friend Dick marry Nell so that the two can split in the old man's supposed treasure: "The other stood lounging with his foot upon a chair, and regarded him with a contemptuous sneer. He was a young man of one-and-twenty or thereabouts; well made, and certainly handsome, though the expression of his face was far from prepossessing, having in common with his manner and even his dress, a dissipated, insolent air which repelled one. [Chapter II, 8]

On the other hand, Dick Swiveller offers considerable comic relief in both the text and accompanying illustration. Whereas Phiz in his original plate Mr. Swiveller Seeks to Gain Attention seems to favour the more serious of the two young men, Fred Trent, Green's characterisation of both young men seems far more astute. Green has absorbed every detail in Dickens's description of the cigar-smoking, rum-drinking law clerk Richard 'Dick' Swiveller — Fred's manipulated friend who works in the law office of Sampson Brass and the Marchioness's guardian. Phiz would probably have had no notion that the boozy, pimply youth in the armchair would eventually free himself of Fred's dubious friendship and plotting to become the novel's secondary protagonist. He eventually inherits money, and marries the Brasses' maid, whom he has dubbed "The Marchioness."

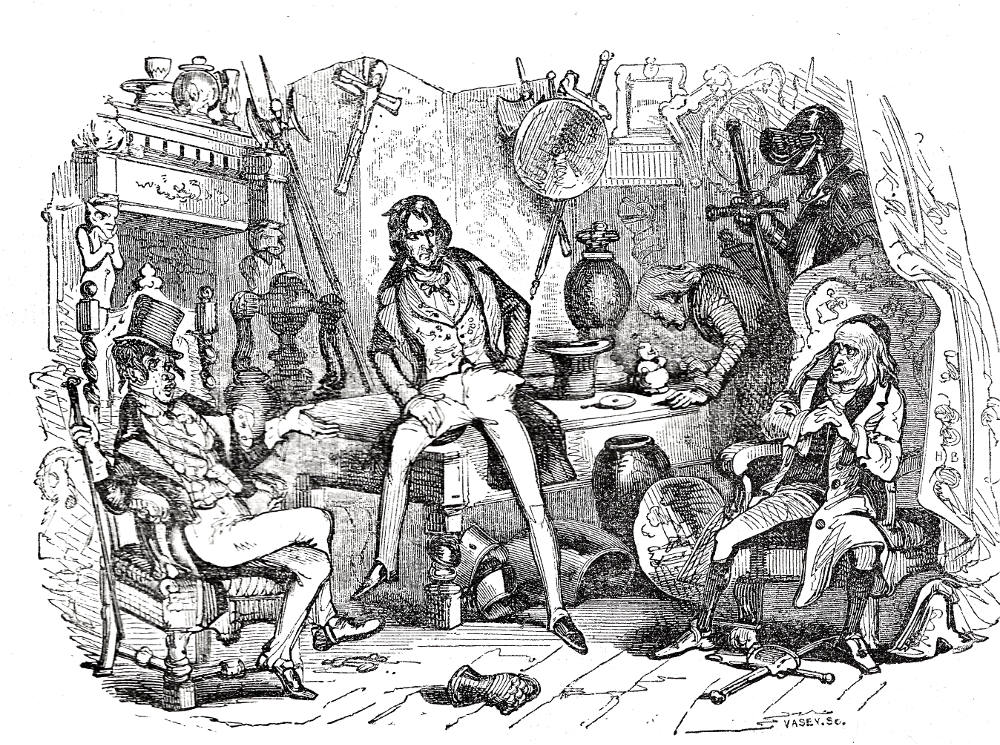

Phiz's and Worth's versions of the same scene (1840 and 1872)

The style of the leading member of the team of illustrators, Phiz, was well suited to the realisation of the odd trio meeting in the quaint interior of the London antique, Mr. Swiveller Seeks to Gain Attention (Part 2: 16 May 1840).

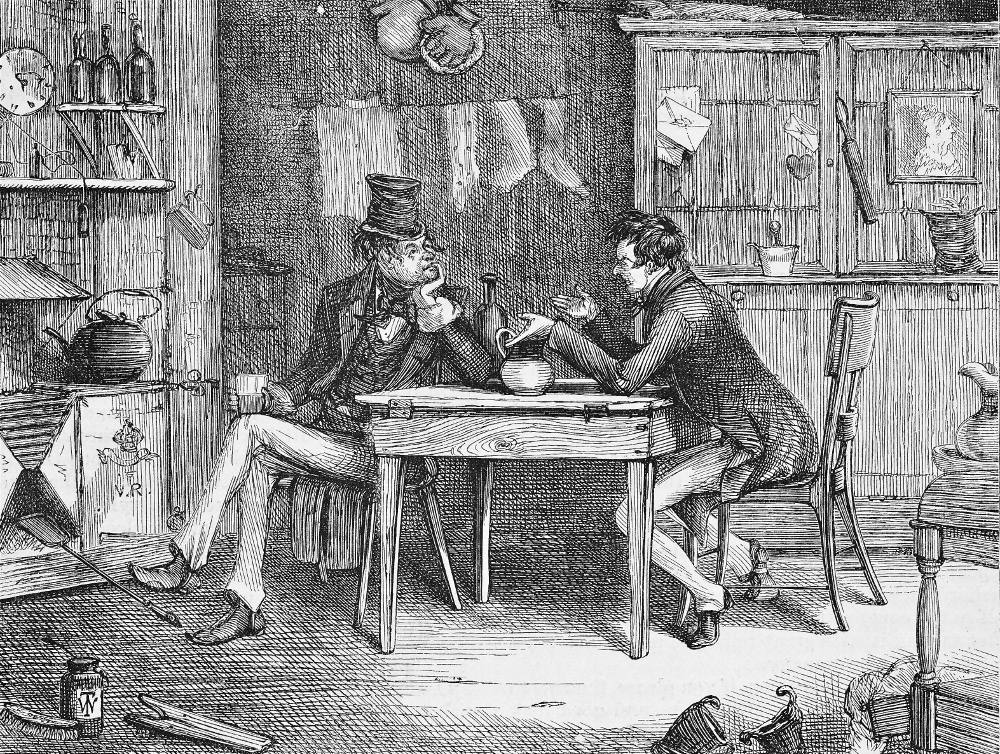

Thomas Worth in a markedly realistic manner describes the general untidiness of Dick's rooms and his lifestyle in general in "Whether he lives or dies, what does it come to?" (1872).

Relevant Illustrations from various editions

- O. C. Darley's Little Nell and her Grandfather (1888)

- O. C. Darley's Dick Swiveller and Quilp (1888)

- O. C. Darley's The Fugitives (Frontispiece, Vol. 2, 1861)

- O. C. Darley's "Marchioness, your health. You will excuse my wearing my hat . . ." (Frontispiece, Vol. 3, 1861)

- Kyd's Player's Cigarette Card watercolours, No. 11: Dick Swiveller (1910)

- Kyd's Characters from Dickens; watercolours: Dick Swiveller

- Harry Furniss's illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop (1910)

Other Artists' Illustrations for Dickens's The Old Curiosity Shop (1841-1924)

- George Cattermole (13 plates selected)

- Hablot Knight Browne (61 wood-engravings)

- Felix O. C. Darley (4 photogravure plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- Thomas Worth (47 wood engravings)

- W. H. C. Groome (9 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (13 lithographs from watercolours)

- Harry Furniss (31 lithographs plus engraved title)

- Harold Copping (2 chromolithographs selected)

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography: The Old Curiosity Shop (1841-1924)

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz, George Cattermole, Samuel Williams, and Daniel Maclise. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury and Evans, 1849.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Thomas Worth. The Household Edition. New York: Haper & Bros., 1872.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by William H. C. Groome. The Collins' Clear-Type Edition. Glasgow & London: Collins, 1900.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. V.

Hammerton, J. A. "XIII. The Old Curiosity Shop." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. 170-211.

Kitton, Frederic George. "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne), a Memoir, Including a Selection From His Correspondence and Notes on His Principal Works. London, George Redway, 1882.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Matz, B. W., and Kate Perugini. Character Sketches from Dickens. Illustrated by Harold Copping. London: Raphael Tuck, 1924.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Created 27 November 2019

Last modified 7 October 2020