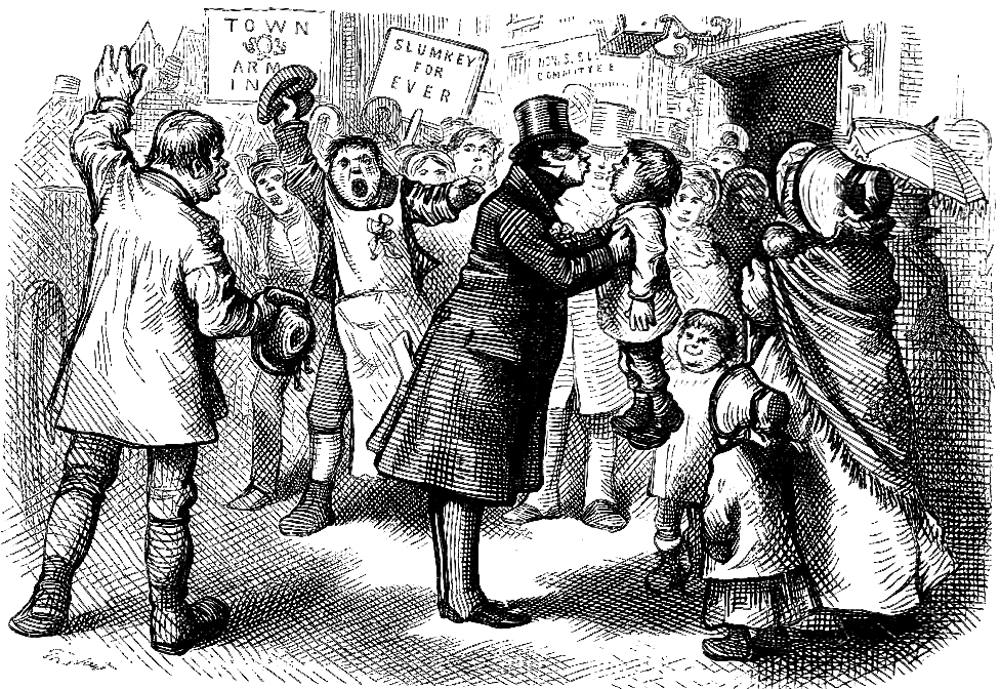

"He's kissing 'em all!" by Thomas Nast (1873)

Bibliographical Note

The illustration appears in the American Edition of Charles Dickens's The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club, Chapter XIII, "Some Account of Eatanswill; Of the State of Parties Therein; And of the Election of a Member to Serve in Parliament for that Ancient, Loyal, and Patriotic Borough," page 81. Wood-engraving, 3 ½ inches high by 5 ¼ inches wide (9 cm high by 13.5 cm wide), vignetted, half-page; referencing text on the preceding page; descriptive headline: "Electioneering Progress" (p. 81). New York: Harper & Bros., Franklin Square, 1873.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Context: Playing to the voters in the Eatanswill election

Amidst the cheers of the assembled throng, the band, and the constables, and the committee-men, and the voters, and the horsemen, and the carriages, took their places — each of the two-horse vehicles being closely packed with as many gentlemen as could manage to stand upright in it; and that assigned to Mr. Perker, containing Mr. Pickwick, Mr. Tupman, Mr. Snodgrass, and about half a dozen of the committee besides.

There was a moment of awful suspense as the procession waited for the Honourable Samuel Slumkey to step into his carriage. Suddenly the crowd set up a great cheering.

"He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as their position did not enable them to see what was going forward.

Another cheer, much louder.

"He has shaken hands with the men," cried the little agent.

Another cheer, far more vehement.

"He has patted the babies on the head," said Mr. Perker, trembling with anxiety.

A roar of applause that rent the air.

"He has kissed one of 'em!" exclaimed the delighted little man.

A second roar.

"He has kissed another," gasped the excited manager.

A third roar.

"He's kissing 'em all!" screamed the enthusiastic little gentleman, and hailed by the deafening shouts of the multitude, the procession moved on. [Chapter XIII, "Some Account of Eatanswill; Of the State of Parties Therein; And of the Election of a Member to Serve in Parliament for that Ancient, Loyal, and Patriotic Borough," page 80]

Commentary: Politician Kisses Infant

The election is not nearly the raucous, partisan affair that Phiz's original 1836

steel-engraving suggests as the Household

Edition illustrators on either side of the Atlantic reduce electioneering to kissing

children. However, at least the recipients of the candidate's osculation in the Phiz

illustration are babes in arms; Nast, who was something of a cynic about politics owing

to his New York City experiences with corruption and coercion, depicts the child being

kissed by Slumkey as neither a toddler not entirely willing; in fact, the child about to

be honoured seems stunned as a consequence of his having been lifted five feet off the

ground by a complete stranger.

The election is not nearly the raucous, partisan affair that Phiz's original 1836

steel-engraving suggests as the Household

Edition illustrators on either side of the Atlantic reduce electioneering to kissing

children. However, at least the recipients of the candidate's osculation in the Phiz

illustration are babes in arms; Nast, who was something of a cynic about politics owing

to his New York City experiences with corruption and coercion, depicts the child being

kissed by Slumkey as neither a toddler not entirely willing; in fact, the child about to

be honoured seems stunned as a consequence of his having been lifted five feet off the

ground by a complete stranger.

When Dickens wrote the chapter, the Great Reform Bill of 1832 was still recent history, and the extended franchise undoubtedly impacted the subsequent bye-elections that young shorthand reporter covered, including the local election at Bury St. Edmunds, which seems to have inspired Dickens to create Eatanswill, Essex. Nast's subject is not "Buff" (Tory or Conservative) Samuel Pickwick, retired capitalist and opponent of wide-scale social change; rather, Nast focusses on "the Honourable Samuel Slumkey himself, in top-boots, and a blue neckerchief," playing to the multitude assembled in front of the Town Arms Inn. The bands and banners appear in the original Phiz illustration, but in neither Household Edition volume:

There were bodies of constables with blue staves, twenty committee-men with blue scarfs, and a mob of voters with blue cockades. There were electors on horseback and electors afoot. There was an open carriage-and-four, for the Honourable Samuel Slumkey; and there were four carriage-and-pair, for his friends and supporters; and the flags were rustling, and the band was playing, and the constables were swearing, and the twenty committee-men were squabbling, and the mob were shouting, and the horses were backing, and the post-boys perspiring; and everybody, and everything, then and there assembled, was for the special use, behoof, honour, and renown, of the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, of Slumkey Hall, one of the candidates for the representation of the borough of Eatanswill, in the Commons House of Parliament of the United Kingdom. [Chapter XIII, page 80]

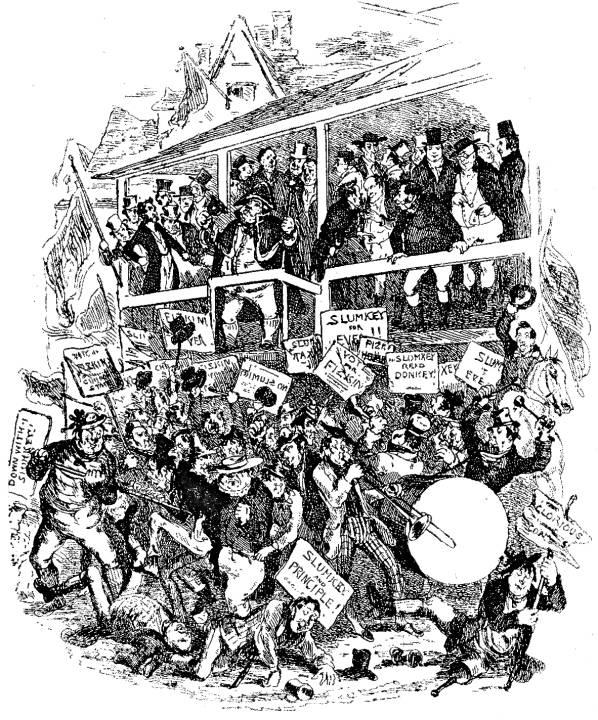

Although the nature of elections in support of British parliamentary democracy must have become somewhat less adversarial, corrupt, and raucous between 1834 (the date of the Sudbury by-election covered by young reporter Charles Dickens) and the 1870s, Phiz merely reprised the 1836 engraving The Election at Eatanswill (Part 5: August 1836) for his 1873 woodcut for the British Household Edition. Whereas Phiz's baby-kissing candidate, Slumkey, seems to have some tender regard for the infant he is about to kiss (centre), Nast's great-coated politician holds aloft a seemingly paralyzed toddler. The comparable juxtaposition of the candidates, the crowd — more raucous in the American version, more benign in the British — as a backdrop, and in particular an almost identical positioning of the sign "Slumkey for ever" (left rear) suggests that one artist was responding to the other's work. In the crowd in the British illustration, the young mothers and their infants predominate — Phiz includes eleven young women and nine children, six of them babes in arms. In contrast, Nast has included only three children and one baby; and his Slumkey supporters are largely male.

The instigator of this electoral strategy for Samuel Slumkey is none other than than attorney Perker, who had negotiated earlier with Jingle at the White Hart in the Borough (Southwark) on behalf of Mr. Wardle. We may assume that, since neither Pickwick nor his comrades appear in either illustration, the perspective from which we see each scene is theirs. The vociferous supporters whom Nast describes, a labourer in linen smock-frock and a butcher in a cotton bib, do not seem to traditional Tory enthusiasts; in fact, these are the very proletarians whom Conservatives sought to exclude from the electorate. Consequently, Nast seems to be implying that they have been suborned or bribed into rallying enthusiastically for the establishmentarian candidate.

Another approach: Phiz's electioneering scene in the British Household Edition (1873)

Phiz's approach to this episode in the novel is completely consistent with that which he took in his 1836 steel engraving "He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as their position did not enable them to see what was going forward.

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Hablot Knight Brown (1836-37)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Hablot Knight Browne (1874)

- A selected list of illustrations by Harry Furniss for the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustration for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Related Material

- Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- Nast’s Pickwick illustrations

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz for the Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Robert Seymour and Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman & Hall, 1836-37; rpt., 1896.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Last modified 13 November 2019