Introduction

Thomas Nast created 52 illustrations for the 1873 Household Edition of Pickwick Papers issued by Harper & Bros., New York. Typically, these illustrations, with the exception of a few full-page character studies, are set horizontally in the middle of a page and are 10.3 cm high by 13.4 cm high on a double-columned page approximately 21 cm high. Thus, each plate occupies approximately half of the page. The print is sharp, but quite fine, so that the entire book is 332 pages, exclusive of a four-page Harper's "advertiser" for its "Valuable Standard Works." In contrast, the British Household Edition, issued the following year, is printed on heavier paper, has larger type, and has each page framed as well as double-columned, in more accurate imitation of the original Household Words format. With larger type, the Chapman and Hall text is 400 pages (there is no "advertiser"). In size and juxtaposition on the page, Phiz's fifty-seven illustrations are similar to Nast's fifty-two. However, Chapman and Hall provide a two-and-a-half page index (pp. x-xii) to Phiz's illustrations, while the Harper and Brothers' text has no such index for Nast's. Phiz has provided four full-page illustrations, running about one to one hundred pages of letter-press; Nast begins with two full-page illustrations, then provides three others throughout the text.

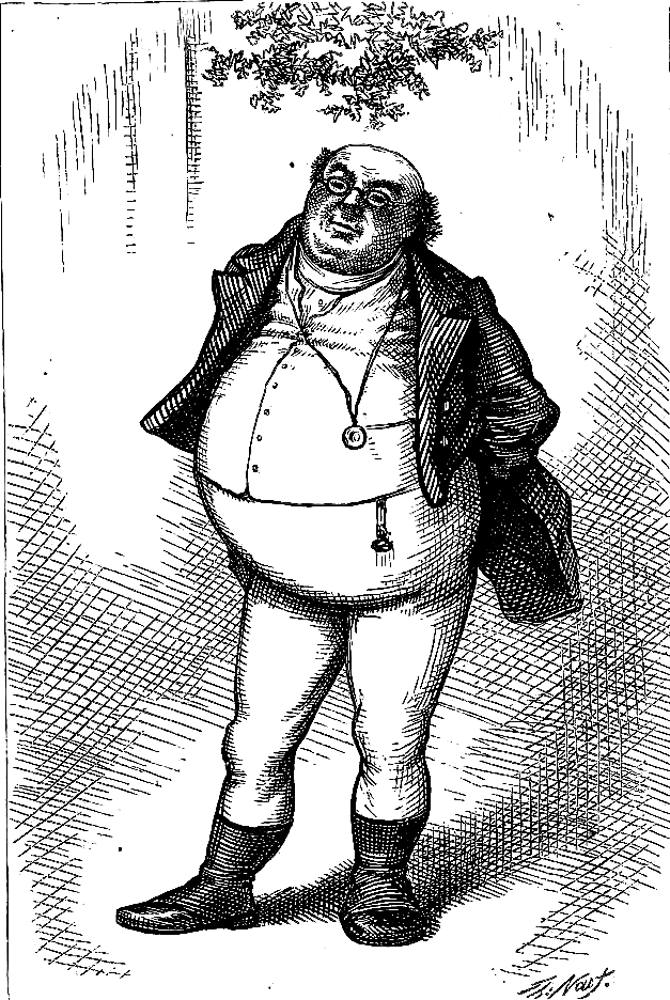

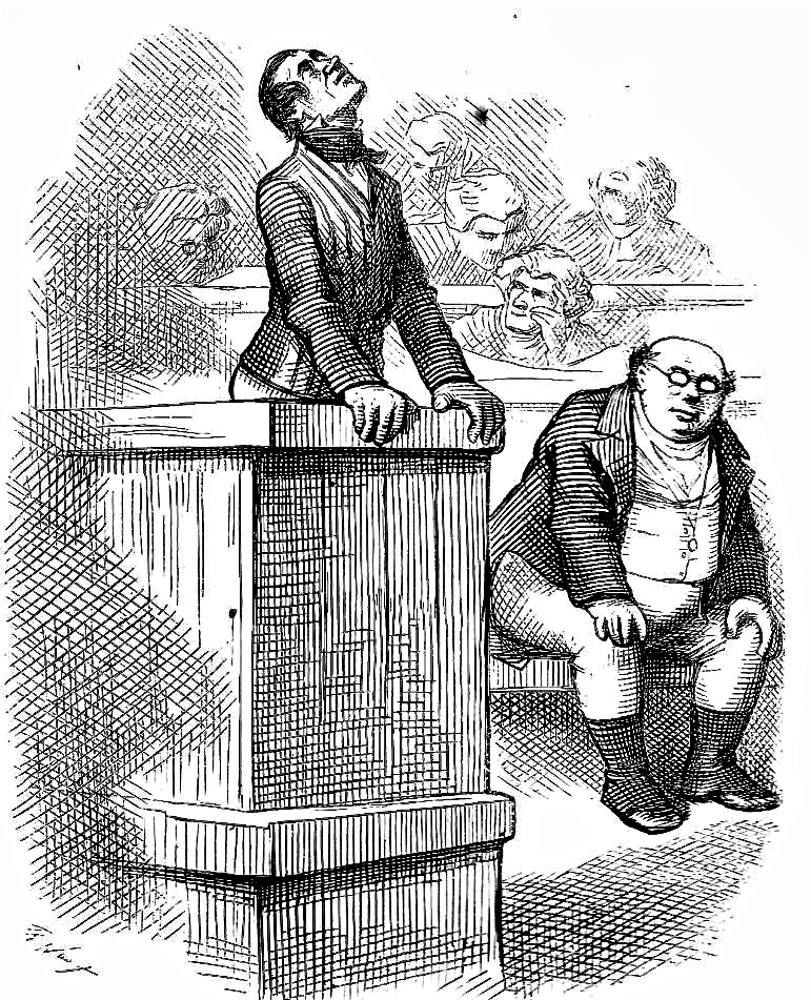

In choosing subjects for his illustrations, Nast had to decide if he should follow the original illustrations of Seymour and Phiz, or if he should he place his own stamp on Dickens’s time-honoured scenes and characters. How much did later illustrators in general such as Nast feel constrained to conform to the precedents for Dickens's originals established by earlier illustrators such as Cruikshank, Leech, and (above all) Phiz? Barnard and other later illustrators of the Household Edition seem to have been mindful of the work of the earlier illustrators for serials such as Pickwick and Oliver. Certainly Barnard has not departed significantly from the lineaments of such well-known characters as Seth Pecksniff in Chuzzlewit. Thomas Nast could have felt somewhat limited in his artistic choices when working with images of such popular characters as Pickwick and Sam Weller. These same constraints, however, do not seem to have been applied to minor characters such as Jingle and Wardle, or to most of Dickens's female characters such as Mrs. Bardle and Rachael Wardle. Nast also reinterprets familiar illustrations. For example, unlike Seymour, who shows Pickwick from the front in his opening plate, Nast has chosen a vantage point behind the speaker that emphasizes the Pickwickians to whom the chair (not Pickwick at all, but the club's secretary, Joseph Smiggers) is speaking, and then, in the second, shifts the focus to his conventional image of the society's founder, rotund, bespectacled Samuel Pickwick. Pickwick gestures grandly with one hand under his coat-tails, exactly as in Seymour's introductory illustration, but Nast has moved in for the closeup, and depicts only two other Pickwickians with any conviction. Perhaps Nast here modifies Seymour's interpretation of this opening scene in an effort to surpass it, and thereby establish himself in the minds of American readers, as a thoroughly contemporary illustrator. His Pickwick here is a dynamic giant among an audience of complacent smokers and drinkers. Nevertheless, Nast's Pickwick here and in the many illustrations that follow very much resembles the Pickwick of Seymour and Phiz.

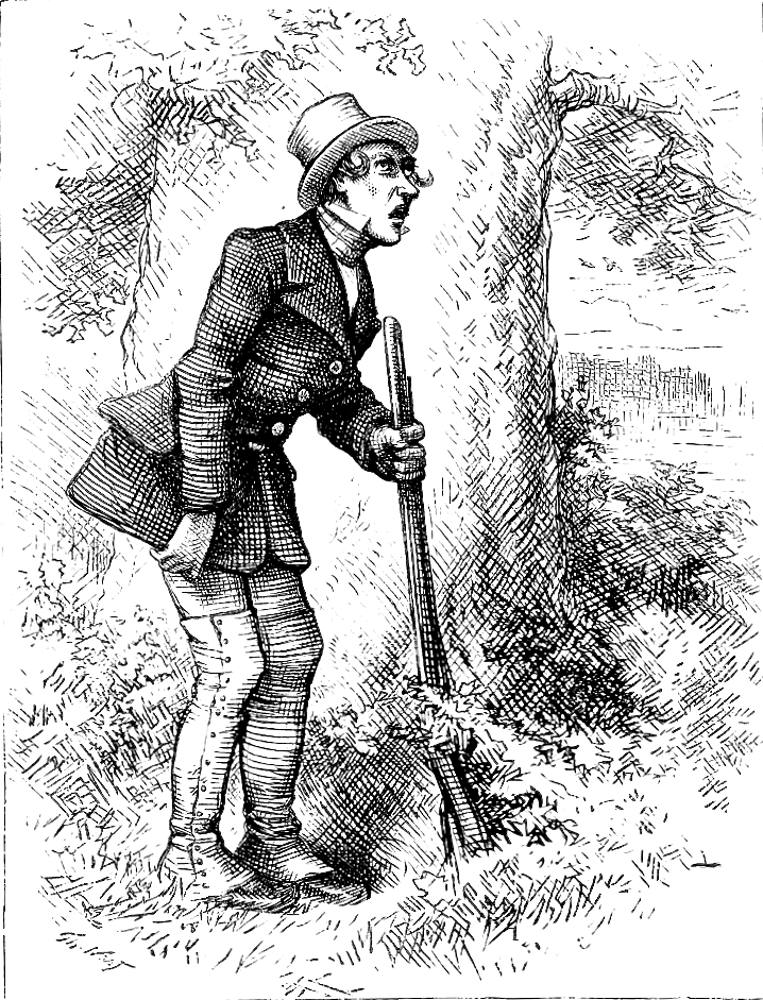

A further complication that Nast effectively confronts is how to represent the other Pickwickians effectively: he simply incorporates the others into his initial plate, in which Joseph Smiggers reads the articles of incorporation to the club. Freed from the obligation to delineate the entire club as Seymour did, Nast took the opportunity to focus on just two characters: the pseudo-sportsman Nathaniel Winkle and the commanding figure of Pickwick himself, speaking above the other members' heads (perhaps literally as well as figuratively), having "mounted into the Windsor chair, on which he had been previously seated" (10). Nast treats his subjects in a three-dimensional manner rather than in a purely caricatural mode, blending the new realism of the Sixties with the earlier, caricatural styles of Hablot Knight Browne and Robert Seymour, with whose original illustrations American readers had been long familiar thanks to such pirated editions as that published in Philadephia by Carey, Lea, and Blanchard in 1836 — in other words, even before serialisation in Britain was complete.

The Illustrations

- 1. Frontispiece, "Went slowly and gravely down the slide with his feet about a yard and a quarter apart." [Page 178]

- 2. "Mr. Pickwick" [Page 162]. Second Frontispiece. [Pickwick under the mistletoe at Dingley Dell]

- Uncaptioned Title-Page Vignette [Sam Weller welcomes the reader.]

- Uncaptioned half-page plate ["Unanimously agreed to resolutions forming the Pickwick Club"] Page 9

- 5. "And addressed club himself had founded." Page 11

- 6. "Have you got everything?" said Mr. Winkle, in an agitated tone. Page 20.

- 7. "Never shall I forget the repulsive sight that met my eyes I turned round." Page 24.

- 8. Mr. Snodgrass seized his revered leader by the coat tail, and dragged him backward. [Page 27]

- 9. Mr. Pickwick displayed that perfect coolness and self-possession, which are the indispensable accompaniments of a great mind. [Page 29]

- 10. "Bless my soul" exclaimed the agonized Mr. Pickwick, "there's the other horse running away!" Page 35

- 11. "To describe the confusion that ensued would be impossible" Page 44.

- 12. "Mr. Tupman" [and Cupid, full-page illustration facing p. 48]

- 13. "He knows nothing of what has happened," he whispered. [Page 52

- 14. "Hurra!" echoed Mr. Pickwick, taking off his hat and dashing it on the floor, and insanely casting his spectacles into the middle of the kitchen. [Page 54]

- 15. "Mr. Winkle. Take your hands off. Mr. Pickwick, let me go, Sir!" Page 57.

- 16. "Is this the room?" murmured the little gentleman. Sam nodded assent. [Page 64]

- 17. "He, too, will have a companion," resumed Mr. Pickwick. [Page 74]

- 18. "He's kissing 'em all!" Page 81

- 19. A most extraordinary change seemed to come over it. [Page 86]

- 20. "Come on, Sir!" replied Mr. Pickwick [Page 91]

- 21. That immortal gentleman completely over the wall. [Pickwick tumbles over the wall of the ladies' seminary] Page 100

- 22. "Sir!" exclaimed Mr. Winkle, starting from his chair. [Page 107

- 23. Mr. Winkle. [in sporting mode, with shotgun; full-page illustration, facing p. 113]

- 24. "Who are you, you rascal?" Page 117

- 25. "Pray do it, Sir!" Page 121

- 26. "She's been gettin' rayther in the Methodistical order lately, Sammy." Page 132

- 27. "Wretch," said the lady. [Page 137]

- 28. "What is the meaning of this, Sir?" [Page 143]

- 29. "Well, now," said Sam. [Page 153

- 30. "I suppose you've heard what's going forward, Mr. Weller?" said Mrs. Bardell. [Page 157]

- 31. "Governor in?" inquired Sam. [Page 159]

- 32. It was a pleasant thing to see Mr. Pickwick in the centre of the group. [At Dingley Dell, under the mistletoe] Page 169

- 33. His eyes rested on a form that made his blood run cold. [Gabriel Grub and the Goblin] Page 172

- 34. "I wish you'd let me bleed you." [Page 177]

- 35. A large mass of ice disappeared. [Page 179]

- 36. "get along with you, you old wretch!" [vignetted, Page 191]

- 37. The particular picture upon which Sam Weller's eyes were fixed. [Page 193]

- 38. "No, I don't, my lord," replied Sam, staring right up into the lantern in the roof of the court. [Full-page illustration facing p. 206]

- 39. Then having drawn on his gloves with great nicety. [Page 209]

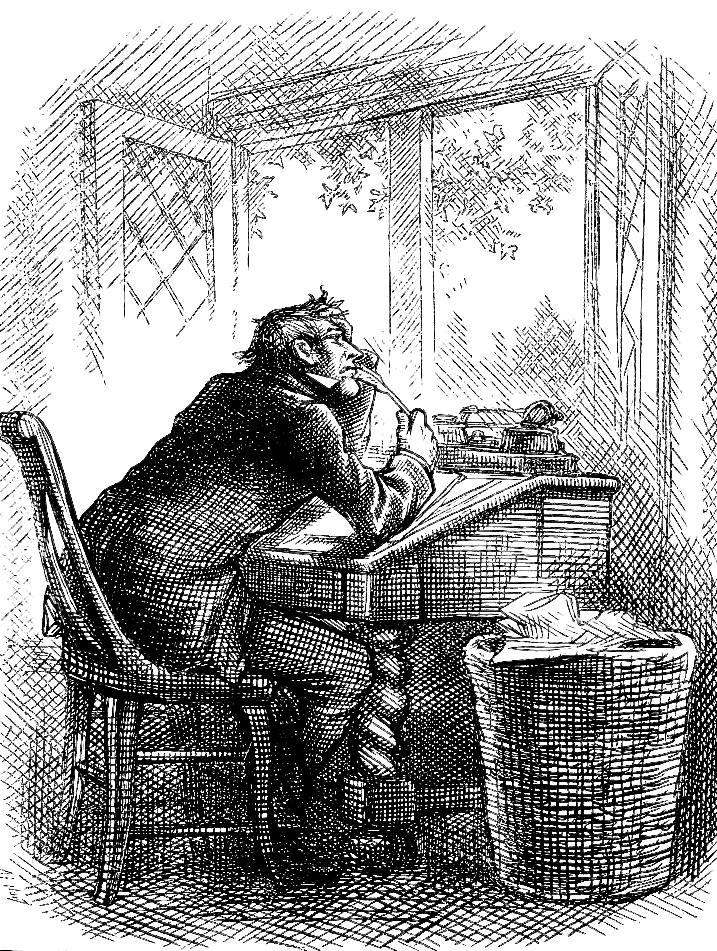

- 40. Having taken a short walk through the city. [Page 214]

- 41. Packed up a few necessaries ready for flight. [Page 220]

- 42. "Bless my soul," every body says, "somebody taken suddenly ill! Sawyer, late Nockenorf, sent for!" [Page 229]

- 43. "Lor do adun, Mr. Weller!" [Page 234]

- 44. "Don't be longer than you can conveniently help, Sir. You're rayther heavy." Page 237

- 45. "Come on — both of you — both of you!" Page 247

- 46. Mr. Stiggins raised his hands, and turned up his eyes. [Page 266]

- 47. The arrival of two most unexpected visitors [Sam and Pickwick]. Page 281

- 48. Resumes his kicking with greater agility than before [Tony Weller vigorously assaults Stiggins at the public house in ch. 52] Page 305

- 49. "Will you have some of this?"said the Fat Boy. [Page 314]

- 50. "All I can say is, just you keep it till I ask you for it again" [Tony Weller entrusts his estate to Pickwick to invest, ch. 54, page 324]

- 51. Mr. Snodgrass [full-page illustration, facing page 331]

- 52. Uncaptioned Tail-piece [Sam Weller and Mr. Pickwick, page 332]

Related Materials

- Interpolated Tales in Dickens's Pickwick Papers

- Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (homepage)

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- The complete list of illustrations by Phiz for the 1874 British Household Edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. New York: Harper and Brothers 1873.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. The Household Edition. Illustrated by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Last modified 14 July 2019