This is a significant and invaluable book which pushes forward the study of Victorian serial fiction. Most modern readers engage with Victorian fiction in large paperback form, almost always lacking the original illustrations, and the authors try to reveal why this difference matters. By exploring archival materials they attempt to bridge the gap between the Victorian and modern reader to create what Catherine Golden has termed “a vital window” into Victorian reading practice. The aim here is to replicate the reading of illustrated serial novels in their original publication formats, issued in parts and over time, and the authors question how these forms suggest specific reading habits with the illustrations not as additional extras but as an integral part of the reading experience. In this quest archival materials are crucial to explore this point, and the writers make a strong case for examining the texts with care and penetration.

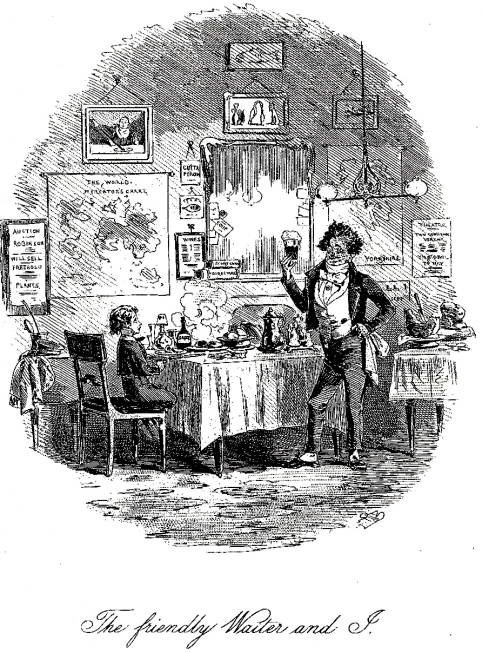

Phiz's young David Copperfield at the coaching inn, where he is less than kindly treated.

They comment on the widespread use of wood engraving as opposed to steel engraving because this had the advantage of being able to print image and text together in the same press. Steel engravings by their intaglio nature meant that each one had to be printed separately and in a different press. There is a cogent commentary on the types and varieties of illustrations before the virtual domination of wood-engraving for illustration which became the extensive form by the 1860s. Nevertheless, several of the novels examined are illustrated by etchings notably by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) for David Copperfield. It is sensible to concentrate on serials because they represent the initial form of distribution of many classic Victorian novels and there is strong discussion of pictorialism in these serials. Even though illustrated texts came to dominate the Victorian serial readership, not all the novelists were happy with the illustrations which were used by the publishers to accompany their texts. A notable example of this displeasure was George Eliot who disliked Frederic Leighton’s designs for Romola, which appeared in the Cornhill Magazine. Similarly in poetry, Tennyson was not happy with the designs employed by Edward Moxon for the celebrated volume of his work which appeared in 1857 with some remarkable and groundbreaking images by Pre-Raphaelite artists.

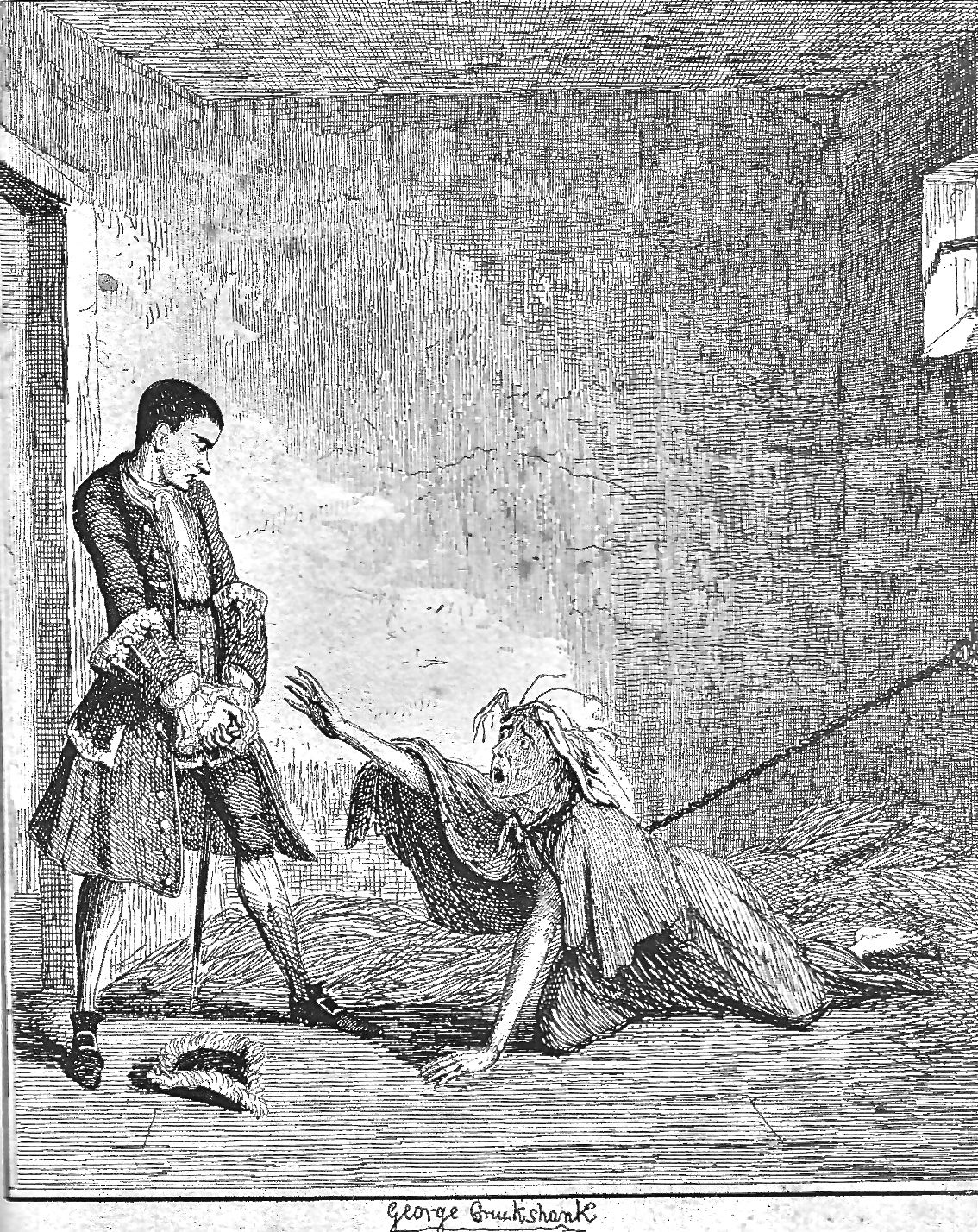

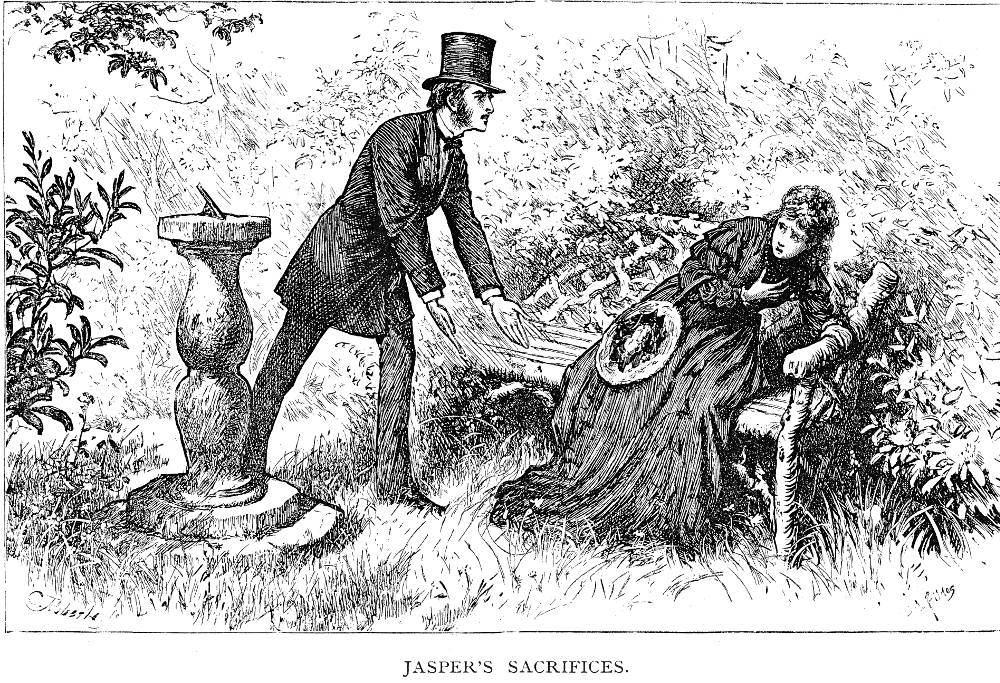

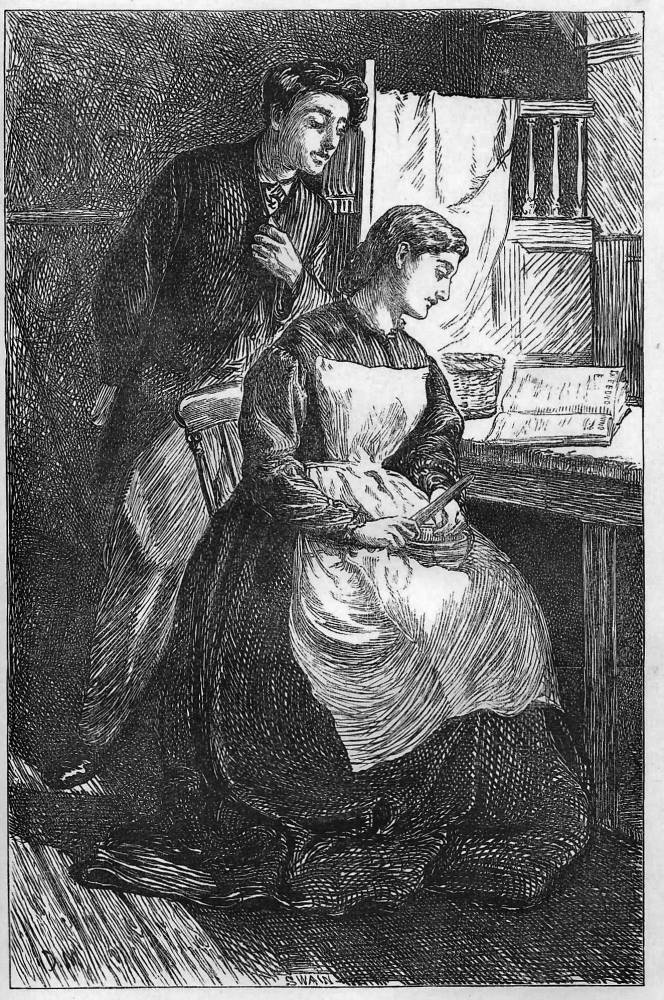

Left to right: (a) Jack Sheppard visiting his mother in Bedlam, as shown by by George Cruikshank. (b) Rosa shrinks from Jasper's "frightful vehemence" in one of Luke Fildes's illustrations for Edwin Drood. (c) Gerald Du Maurier's "word picture" of Cousin Phillis peeling apples while reading Dante’s Inferno.

The authors take a number of case studies to interpret prolepsis and analepsis, the process by which illustrations prefigure or foreshadow what is to come, or reflect on what has happened. The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) with illustrations by Luke Fildes, is carefully examined, with the illustrations often being placed in advance of the relevant text and as as flashbacks. The reader is told of the uniqueness of Drood because it offers a window into Victorian reading practice at variance with most Victorian serials, which do not all provide such clear evidence. A useful example is offered by a close examination of Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard (1839) for which George Cruikshank provided etched designs, several being either proleptic or analeptic. Gaskell’s Cousin Phillis is similarly discussed as the novel was published in The Cornhill Magazine in four parts beginning in November 1863. Du Maurier contributed just a single design, though later he produced further illustrations for Mrs Gaskell’s works. The Cornhill was the premier literary journal of the day and in Du Maurier’s image we see Phillis peeling apples while reading Dante’s Inferno. Both Paul and Phillis are shown in profile and indeed it is a very visual story, with Paul providing “word pictures” of Phillis. The authors argue that both David Copperfield and Cousin Phillis represent selfhood as it is imagined through visual images recalled over time.

Picturing the past with illustration is dealt with in some detail using as just one example W. H. Ainsworth’s The Tower of London (1840) where the reader is encouraged to see how the form of the illustrated serial allowed the recounting of history, the reader knowing the outcome of certain events. There is also valuable coverage of Millais’s designs to the tales of Harriet Martineau, where again the reader is already aware of the historical events being pictured.

Left: The famous scene at the beginning of Vanity Fair, depicted by Thackeray himself, in which Becky Sharp throws her presentation copy of Johnson's Dictionary out of the carriage as she leaves school for the last time. Right: The equally famous scene in A Tale of Two Cities, this time by Phiz, of revolutionary Paris.

Vanity Fair is unusual in that it is illustrated by the author; Thackeray barely includes the Battle of Waterloo and indeed there is a deliberate underlining of historical reconstruction by a deployment of playful anachronism. All this is closely examined and analysed in a manner which seems entirely new and pioneering. For example, the female costumes are depicted in anachronistic form combined with metonyms, with simple signs alerting the reader to the contemporary present rather than the past. Moving on to Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, there is a strong case made for re-valuing Phiz’s designs, the last the artist made for the author. A useful comparison is made between the Phiz images in the English edition and those by McLenan for the American one — the latter showing violence in a manner completely at variance with his English counterpart.

Chapter 3 is entitled “Hallowing the Everyday” and deals with illustration and realism in Gaskell’s Wives and Daughters, Mistress and Maid and Trollope’s The Small House at Allington. Here Millais and Du Maurier are examined in detail, with their emphases being essentially on minor everyday events. Both these artists depict domestic life nobly and poetically, and in this they may be compared with the heroic images of ordinary people made by artists of the French Barbizon school such as Courbet and Millet. As an example, Mollie’s long hair indicates that she is too young to be married. All such similar depicted clues would be read and recognised by the Victorian reader of these novels. Again, it is the penetrating survey of these visual themes which make the book so fascinating. The reader is led through the visual experience of these books with care and foresight.

The Baron hypnotises Rosalie in one of George du Maurier's illustrations for The Notting Hill Mystery

In Chapter 4 the authors turn their attention to the popular sensational novel notably ‘Charles Felix’s’ The Notting Hill Mystery, Charles Reade’s Griffith Gaunt and Wilkie Collins’s The Law and the Lady, all of them a matter of “Arousing the Nerves” in the febrile sixties. The Notting Hill Mystery is illustrated by du Maurier and the emphasis on mesmerism is acutely depicted by him with several key moments captured with force and vitality. The designs are an integral part of the action and the authors are correct to stress just how apt they are for the action: the reader is told of the ‘serial’s trope of collapsed bodies’ being important in bringing home the themes of the story and ‘visual shock’ which is so intrinsic a feature of sensation fiction. The illustrator of Griffith Gaunt is the underrated artist William Small, who provides racy scenes to match Reade’s excess. Here, the reader is told, quite correctly, that horses play an important part in the illustrations and that ‘The horse stands as a primary symbol for passion’. Such insights would be immediately recognised by the Victorians, but they would be completely lost on the modern reader. The close analysis of both the text and the designs of these three novels is perceptive, and the authors go into valuable depth. With ‘The Lives and After-lives of illustrated Victorian Serials’ the book comes to its conclusion, mentioning that so many of these works with their illustrations are self-reflexive in their very nature. The cover of the book shows the 1873 portrait of Effie Millais painted by her husband. She is holding on her lap a recognisable copy of the Cornhill Magazine. Not for nothing did one of the period’s greatest illustrators of serial fiction depict his wife in so deliberate and self-conscious a manner. Leighton and Surridge have produced an immensely important and profound volume and by their efforts have set before the reader the concept that illustration studies might become a subject itself worthy to be taught at post-graduate level. Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. The Plot Thickens – Illustrated Victorian Serial Fiction from Dickens to Du Maurier. Athens Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2019. 331 pp. (including numerous black and white illustrations and index). ISBN 9780821423349. $70.00. Created 2 July 2019Book under Review