The following passage, from Notes of a Son and Brother, the second of his autobiographical volumes, provides powerful evidence of the great importance the appearance of The Cornhill Magazine had upon Victorian readers. I have transcribed it from the Project Gutenberg online edition, adding links, images, and italicized titles. Most of the links on the names of Victorian authors take you to James’s complete essays or other remarks on them. — George P. Landow

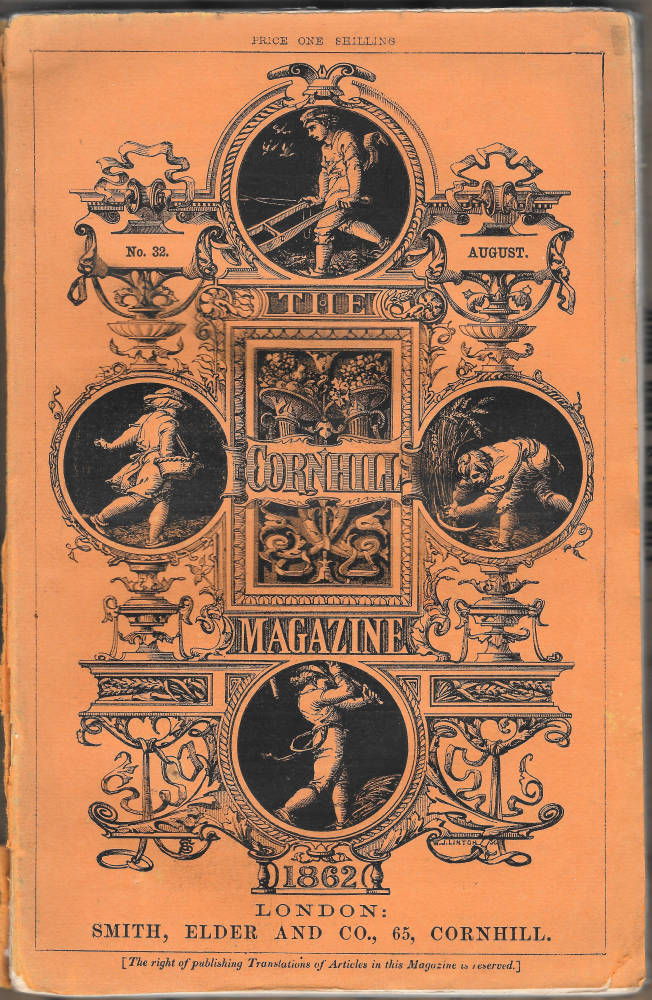

ith which mild memories thus stands out for me too the lively importance, that winter, of the arrival, from the first number, of the orange-covered earlier Cornhill—the thrill of each composing item of that first number especially recoverable in its intensity. Is anything like that thrill possible to-day—for a submerged and blinded and deafened generation, a generation so smothered in quantity and number that discrimination, under the gasp, has neither air to breathe nor room to turn round? Has any like circumstance now conceivably the value, to the charmed attention, so far as anything worth naming attention, or any charm for it, is anywhere left, of the fact that Trollope's Framley Parsonage there began?—let alone the still other fact that the Roundabout Papers did and that Thackeray thus appeared to us to guarantee personally, intimately, with a present audibility that was as the accent of good company, the new relation with him and with others of company not much worse, as they then seemed, that such a medium could establish. To speak of these things, in truth, however, is to feel the advantage of being able to live back into the time of the more sovereign periodical appearances much of a compensation for any reduced prospect of living forward. For these appearances, these strong time-marks in such stretches of production as that of Dickens, that of Thackeray, that of George Eliot, had in the first place simply a genial weight and force, a direct importance, and in the second a command of the permeable air and the collective sensibility, with which nothing since has begun to deserve comparison. They were enrichments of life, they were large arrivals, these particular renewals of supply—to which, frankly, I am moved to add, the early Cornhill giving me a pretext, even the frequent examples of Anthony Trollope's fine middle period, looked at in the light of old affection and that of his great heavy shovelfuls of testimony to constituted English matters; a testimony of course looser and thinner than Balzac's to his range of facts, but charged with something of the big Balzac authority. These various, let alone numerous, deeper-toned strokes of the great Victorian clock were so many steps in the march of our age, besides being so many notes, full and far-reverberating, of our having high company to keep—high, I mean, to cover all the ground, in the sense of the genial pitch of it. So it was, I remember too, that our parents spoke of their memory of the successive surpassing attestations of the contemporary presence of Scott.

Related material

Bibliography

James, Henry. A Small Boy and Others. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913. Project Gutenberg online version produced by Chuck Greif, Martin Pettit, University of Toronto Libraries, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

James, Henry. in Autobiography. Ed. F. W. Dupee/ New York: Criterion Books, 1956.

James, Henry. Notes of a Son and Brother. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913. Project Gutenberg online version produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

Last modified 16 April 2020