n the midst of the extra burden imposed by writing a huge number of biographies for Fisher’s National Portrait Gallery, Jerdan became immersed in developing a new project, an idea for a Foreign Literary Gazette. He had a financial and active partner in this venture, a Captain Williams, later to become an Inspector of Prisons. (Always keen to take any credit he could, Jerdan speculated that Williams’s experience on the Foreign Literary Gazette cultivated his mind, produced sagacity in the performance of his duties, and lucidity in writing his Blue Book Reports (4.273). He was serious about this, believing that “There are few schools superior to the school of literary reviewing and miscellaneous essay for developing the intellectual faculties and enlarging the understanding.”) There were other staff assisting in producing the new journal; a Mr Smith, who became Secretary to King’s College London, and the faithful Mr Lloyd of the Foreign Post Office who had worked with Jerdan since he started with the Literary Gazette.

An enormous amount of “correspondence, research and application” ensued, resulting in appointment of correspondents “from Petersburgh to Naples”, and publishers in every corner. Jerdan sent Smith off to Belgium, Holland and Germany. Williams went to France, and Jerdan stayed in London pulling whatever strings he could. He canvassed his contacts abroad, and on 26 October 1829 he wrote to Lord Burghersh in Florence, reminding him that they had met in Paris in 1814, and that his Lordship’s work had been noticed from time to time in the columns of the Literary Gazette (Bodleian c. 4862). Jerdan outlined his plan to “make this new journal to Foreign what the Literary is to English literature”. He asked his Lordship’s assistance in garnering information concerning “interesting works – correspondence of able men – Reports of learned and Scientific Institutions – notice of what is new in Antiquities, the drama, music, the fine arts etc. etc.” The plan had been approved throughout the Continent, he explained, but he needed co-operation in Italy, which he hoped Burghersh could help to procure with his influence.

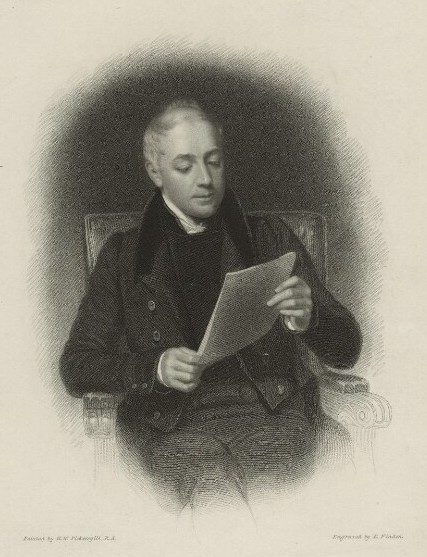

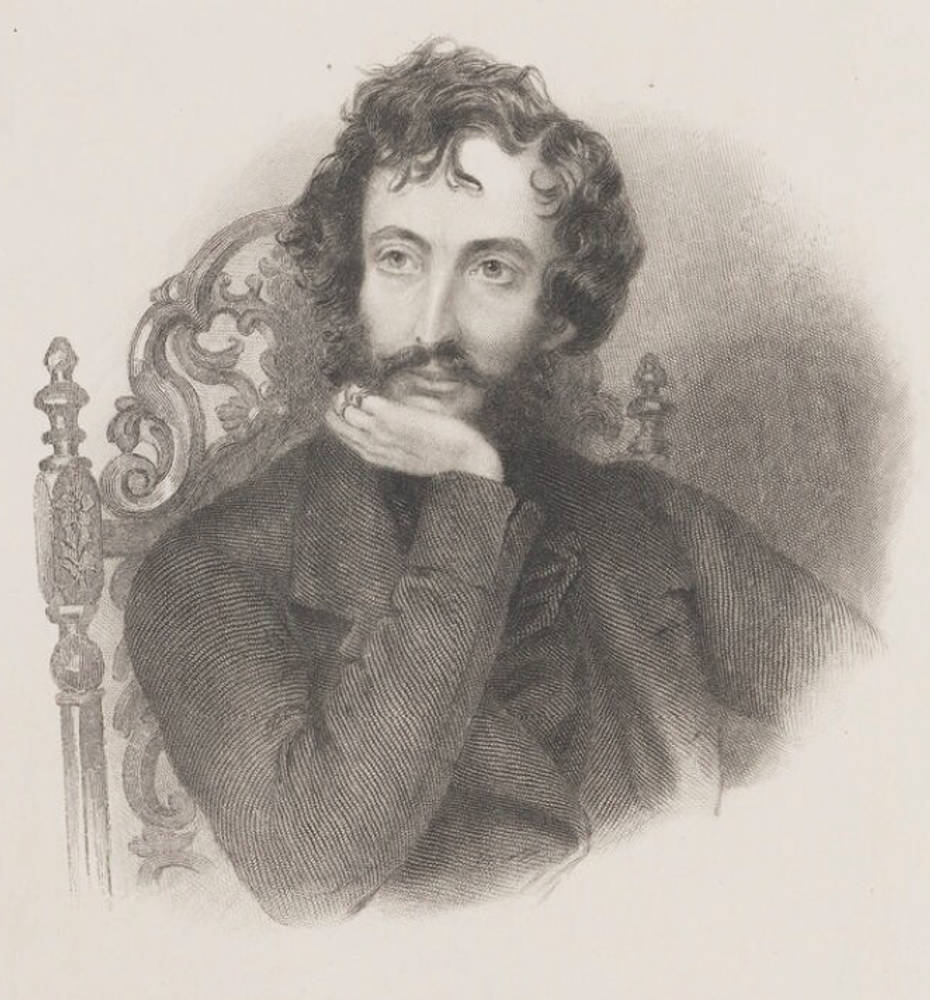

John Murray (1791-1857), engraved by E. F. Finden after H. W. Pickersgill.

Jerdan tried to interest John Murray in joining him in this venture, but without success. Murray had asked Messrs Longman if they intended to participate, but receiving no satisfactory reply, declined Jerdan’s offer. He also said that he would be “a restless and teasing partner” preferring to act alone (4.274). Jerdan also approached his partners in the Literary Gazette, the Longmans and Colburn, who debated for a long time about investing £500 each. They eventually declined. Jerdan thought it was because they were concerned that it would distract him from his duties on the Literary Gazette, which was then “a very lucrative investment.” This was probably a correct surmise as the printer Scripps wrote to Jerdan telling him that Mr Orme of Longmans was very displeased to see the Scripps name connected with advertisements and bills for the Foreign Literary Gazette, and asked for this to be discontinued (Bodleian d. 114, f205).

All Jerdan’s plans were in place, his overseas agents ready to send in their contributions and he still did not know how he was to produce the new journal. His failure to attract investment contributed largely to the failure of the project, but somehow thirteen issues were produced, between January and March 1830. The Age, never a friend to Jerdan, nevertheless remarked on 24 January 1830 that the new publication reflected “great credit on the Editor Mr Jerdan, not only for the originality of the information it conveys, but for the excellent style in which the various articles are written.” Thomas Carlyle commented to a German correspondent on 20 March 1830 that Britain had already two Foreign Reviews which were prospering, and there was now a third. “We have a Foreign Literary Gazette published weekly in London and which tho’ it is a mere steam-engine concern, managed by an utter Dummkopf solely for lucre, appears to meet with sale. So great is the curiosity, so boundless is the ignorance of men” (Carlyle to J P Eckermann . Carlyle Letters Online (CLO)). Carlyle’s optimism was misplaced, as was his unkind remark about Jerdan, who was working hard on the project, but it was not enough. The Literary Gazette of 6 March declared that as the publication’s first two months had been completed, “it would be a sacrifice of our opinion to ultra-delicacy were we to altogether avoid calling our readers’ attention to it.” Jerdan did so in a brief paragraph, saying that the mass of information in its pages was “both instructive and entertaining”. As well as a lack of investment from his partners, Jerdan blamed the stamp for defeating his project; he also blamed the public for being unwilling to pay two shillings a week for two literary journals, the Foreign on Wednesday and the Literary on Saturday; he blamed too the lack of advertising, especially from the house of Colburn. The whole enterprise had been very expensive – translations from several languages had been costly – and although the issues which did appear had met with approbation, it was not enough to keep the thing afloat, as he told readers of the Foreign Literary Gazette in March 1830:

Thus situated, though we might suppose that a great outlay of capital and a long course of persevering industry would raise this Periodical to that degree of circulation which should reward the proprietors; we are not inclined to resort to the expedients which now seem so necessary to bring any work into general notice. Our public is self-occupied, and nothing but a system of extravagant puffing seems adequate to awaken attention to any literary performance; and rather than resort to that system, we, thanking our friends for their many kindnesses, have resolved to close our well-intentioned labours.

Jerdan reckoned that he and Williams had lost a hundred pounds a week, but comforted himself that it was the best lesson his colleague ever learnt.

The pressure on Jerdan’s time and attention was considerable: the Foreign Literary Gazette had created much work, in addition to the mammoth task he had undertaken for Fisher’s National Gallery of Portraits, and his frequent contributions to the fashionable Annuals, all this to be fitted in around his main occupation of producing the Literary Gazette. As editor of the foremost weekly literary review, Jerdan inevitably got embroiled in various squabbles, some with lasting effect, others petty, blown up out of all proportion.

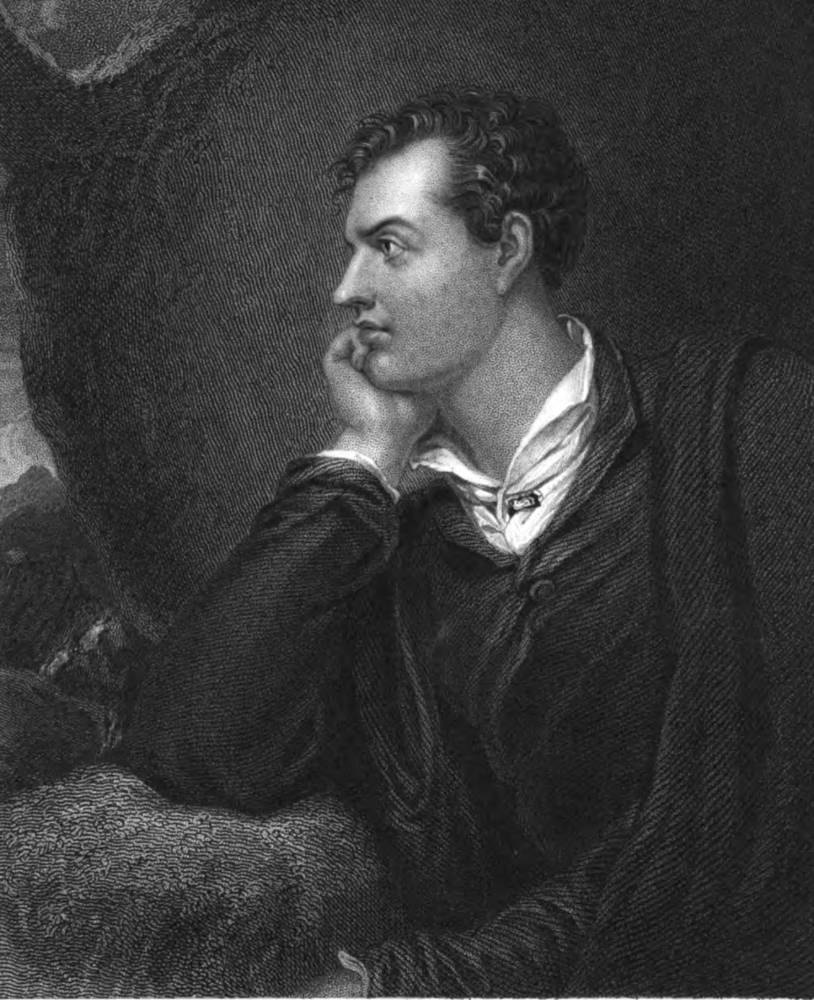

George Gordon Lord Byron. Engraved by H. Robinson after a painting by Richard Westall, R.A.

From the 1840 Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrapbook edited by L.E.L. and Mary Howitt.

His leading review of 16 January 1830 featured a book published by Murray, an instance when Jerdan’s choice trumped a Colburn publication. Volume I of Thomas Moore’s Letters and Journals of Lord Byron with Notices of his Life was given seven pages, mainly extracts, with the eulogy that “Under this modest title we have now before us – whether we consider the subject, the writer, or the performance itself – one of the most interesting pieces of biography that has ever adorned the literature of England.” Lady Byron took offence and on 20 March the Literary Gazette printed ‘Remarks occasioned by Mr Moore’s Notices of Lord Byron’s Life’, reproducing her letter to Moore, which objected to his publishing domestic details prior to her separation from Byron. She maintained that if such details were printed, persons affected had a right to refute injurious charges; she especially resented that her parents were spoken of badly. Jerdan believed that the ‘Remarks’ were legitimate prize to be printed, though ‘unpublished’, and promised to explain his views in the next week’s Gazette. His rather evasive and nit-picking response duly appeared; vindicating his editorial decision in ‘Sketches of Society’ of 27 March, Jerdan informed his readers that “the Literary Gazette is the last Journal to be looked to, either for controversy or for such news as is merely calculated to gratify prurient appetites”. By using italics, he claimed, the Gazette showed that it was incapable of intruding on anyone’s privacy and had merely reprinted a document already in circulation. It was absurd to suppose that Lady Byron’s printed ‘Remarks’ were intended to be kept secret. Triumphantly, the Literary Gazette asserted:

Our sheet, with this exclusive paper, was not dry from the press, when a would-be fashionable contemporary, called in mockery we suppose, The Court Journal, thought fit to attract the public attention by covering London with placards of a second edition, “containing Lady Byron’s Letter to Mr Moore, stolen, within a few hours, from the Literary Gazette – for if the plagiarist had seen the original, he would have discovered that the title was not Letter but Remarks…Now that the Literary Gazette stands so high, that it can very well afford to be plundered in this way (and we never complain of the hundreds of our columns taken daily and weekly into other periodicals, in the ordinary course without acknowledgement).

By 3 April the quarrel had spread, and under ‘Sketches of Society’ the Literary Gazette noted that “this subject continues to be discussed in almost every society and a new filip has been given to it by a determined attack upon Mr Moore and his biography by Mr T Campbell, as a friend to Lady Byron, in the New Monthly Magazine.” Campbell had accused Byron of “some dark crime” and Moore of “screening his hero by disparaging his exemplar lady and her relatives”. Primly, Jerdan remarked that such information had come too late for considered comment, “the matter is too serious and indelicate, not to say disgusting, of being treated of hastily.” He insisted that the Gazette’s publishing of the “Remarks” was fully justified. Pressing his point on 10 April, he again protested against Campbell’s “odious imputations…in the name of all that is honourable in human nature.” Colburn had two of his journals at each other’s throats, so he could not lose as long as readers were kept enthralled by the squabble.

Clearly out of sorts, and contrary to his habitual practice of kindly reviews, or no review at all, Jerdan and the Literary Gazette vented spleen in the issue of July 10, on Charles Lamb’s Album Verses. It accused Lamb of vanity and egotism for printing verses he wrote in young ladies’ albums, whilst he had called them “the proverbial receptacles for trash!” Lamb had said in his dedication that his motive was to benefit his publishers by showing their skills, and accordingly the Gazette’s slashing comments ended with a final rapier thrust, “the title page is especially pretty”. On 17 July 1830, the Athenæum maintained that this harshness was solely because the book was published by Moxon, not by Colburn and, predictably, talked of “a Lamb offering itself for the sacrifice” (435-36). It was believed that Jerdan disliked Lamb for taunting “his hero William Gifford”, and furthermore, an object of Jerdan’s displeasure, Samuel Rogers the Banker Poet, was named in the dedication of Album Verses. Jerdan’s Men I Have Known (1866) treats Rogers with a biting criticism almost unique in his considerable biographical writings. Nonetheless, such vituperation was unusual for Jerdan, giving rise to another theory that it was Landon who wrote the cruel review, as it was too personal to be in Jerdan’s style, and Jerdan had reviewed Lamb kindly some years earlier, in August 1819 (Duncan 65). Landon would have objected to albums being denigrated, as she was so closely involved with them; furthermore, as others like Chorley complained, she could be biting in her reviews. Chorley said, “For years the amount of gibing sarcasm and imputation to which I was exposed was largely swelled by this poor woman's commanded spite" – commanded, he meant, by Jerdan (Chorley 107; quoted Duncan 100).

Southey came out in defence of Lamb in The Times of 6 August, a gracious act as it was his first public utterance on his old school-friend since “Elia’s” famous letter to him some time earlier. Southey’s verse, To Charles Lamb: On the Reviewal of his ‘Album Verses’ in the ‘Literary Gazette’ spoke of Lamb’s “genius”, his “sterling worth”, his lasting name when those of his critics would be forgotten. For good measure Southey attacked not only Jerdan but also Jeffrey, founder, and until July 1829 editor, of the Edinburgh Review. His defence of Lamb ended:

Matter it is of mirthful memory

To think, when thou wert early in the field,

How doughtily small Jeffrey ran at thee

A-tilt, and broke a bulrush on thy shield.

And now, a veteran in the lists of fame,

I ween, old Friend! Thou are not worse bested

When with a maudlin eye and drunken aim

Dulness hath thrown a “jerdan” at thy head.*

*(a pun, ‘jordan’ being an Elizabethan term for chamber-pot)

The Athenæum praised Southey for picking up the cudgels, especially as his name was distinguished and influential. It warned, “unless there be more discretion both in the praise and censure of the Literary Gazette, not all the interest of Messrs, Longman and Co. and Colburn and Bentley, whose property it is, can uphold that paper” (7 August 1830, 491).

Leigh Hunt’s old paper, The Examiner, was also unhappy with Jerdan. In ‘Rejected Epigrams, offered to, but not accepted by the editor of a weekly publication’ signed T.A. There appears to be no concensus as to the identity of “T.A.” One source, E.V. Lucas’s The Life of Charles Lamb suggests that Lamb might have written the final epigram, but another doubts this as one of the epigrams is addressed to Lamb himself. The first and second of these, published in the issue of 15 August 1830 were of two lines each and were heavy-handed and not witty. The third Epigram, although longer, was vicious:

In lanes and at the corners of the streets,

The eye of passengers a caution greets,

Advising them that at that sacred spot

The laws of decency be not forgot,

In terms so plain, the most unletter’d lurdan

Can scarce mistake – save Literary J-----n,

Who thinks he hits the meaning, and the true sense

While in his writing he commits no new sense.

The next attack was even more personal:

If we believe St, Paul and Scripture sense

There are, and must be, “Vessels of Offence”:

And such is one, whose name would dirt our pen,

That casts its water upon blameless men,

Replenished to the brim with stalest ware,

Yet, strange to tell, a favourite with the fair;

And for perversion, with an eye to pelf,

Makes of good things a handle for itself.

Lest Jerdan think this was the worst damage The Examiner could do to him, the paper noted that the Epigrams were “To be continued weekly, till the proprietors of the publication in question shall dismiss their present editor for incompetency and imbecility – an event which is calculated as probable to happen about the first week of October.”

The following week, the fifth epigram addressed itself to L.E.L. advised her to “Come from that unclean cage”, and that her genius “…should scorn – O servile tax/ To be the hack to booksellers vile hacks.” T.A. warmed to his task, and the sixth epigram warned:

The number of the dunces, dunce by dunce;

There were four hundred, if I don’t forget,

The readers of the Literary Gazette:

But if the author to himself keep true

In some short months they’ll be reduced to two.

Several more Jerdan-attacking squibs followed, including one on 12 September, poking fun at Jerdan’s attribution to Shakespeare of a modern poem, a trap into which Jerdan had readily fallen: “To shew what Shakespeare did not write is easy/But what he did! J-----n I see you’re queasy.”

Leigh Hunt printed an ‘Inquest Extraordinary’ in the first issue of his Tatler on 4 October 1830:

Last week a porter died beneath his burden;

Verdict: Found carrying a Gazette from Jerdan.

Same day, 5 September 1830, in the Age:

Two gentlewomen died of vapours,

Verdict: Hair curl’d with Mr Jerdan’s papers.

The next issue carried Objections to the “Lines on Jerdan”:

Why, Mr TATLER, should you tell

The world a truth it knows so well?

That JERDAN is a dunce we know,

For every week he tells us so.

Sure, Mr TATLER, you conferred an

Honour unmerited on JERDAN,

Saying his intellect was small;

’Twas thought that he had none at all.

Hunt’s Tatler was short-lived, closing in February 1832.

Lamb received a note of comfort from Bernard Barton following the Literary Gazette review, and replying on 30 August assured him, that the sight of annuals made him sick, and further, that “They are all rogues who edit them, and something else who write in them.” His ire was excited by Jerdan’s unnecessarily cruel review, especially in a journal so renowned for its habitual kindness. Jerdan was, apparently, not in his usual generous frame of mind and had created a row over a trifle that a respectable literary journal might have been well advised to ignore. He mentioned nothing of all this furore in his Autobiography, neither did he take it further in the Literary Gazette, possibly because Landon had written the offending review, or because he generally tried to avoid personal controversy, especially as in this case he must have felt outnumbered and outgunned.

Another rare glimpse of his irritability is apparent in a letter of 8 February 1830 he wrote to William Blackwood in Edinburgh requesting his friend and rival to reconsider a book sent to him for review three months earlier; he followed this with “I dare not do more than suggest to such a Wizard as Ebony, but I think if he will look at …he will find quotations fit for his various page; and he will oblige me by paying as early an attention to this recommendation as I am always inclined to pay to any from him” (National Library of Scotland, 4027/236-7). He must have felt the fates conspiring against him, although he was at the peak of his powers at this time: he told ‘Ebony’ that “LEL is also shelved I fear – so that I fear it will be fearful for you to venture to London this Spring” . He does not explain why L.E.L. was “shelved” but if she was indisposed, he would have had an extra burden of work to get through on the Literary Gazette, which would not have improved his temper, and at the same time, the great issue of ‘puffing’ was gathering steam. He was in need of all the support he could get. Crossly, he told ‘Ebony’ in his postscript: “By the bye, why do your Editors fling at me – the ill-will is but slight and I regard it not; but it should not appear in a friend’s publication. Instead therefore I have contributed to the Annuals (fairly enough for a busy body – have put my name to the National Gallery of Portraits, and have set up a New (Foreign) Lit Gazette in all of which you might have given me a good office.” He presumably meant ‘puffs’ in Maga, which were not forthcoming.

One of his contributions to an annual was to The Keepsake of 1830, a poem entitled “The Time Was – And Is,” a clumsy title for a sad poem about drinking and singing with friends in earlier days; they are now dead, and wine has no power to restore feelings and friends of youth. Jerdan took some time off to accompany Wordsworth to the Royal Academy exhibition; they inspected J. M. W. Turner’s painting of ‘Jessica’, Shylock’s daughter, which Jerdan thought “an outrageous slapdash”. The future Poet Laureate went further: “She looks as if she had supped off underdone pork, and been unable to digest it in the morning” (Men I Have Known 480).

There was considerable financial pressure on Jerdan at this time and he was driven to repeat a sacrifice which had cost him dear the first time around. On 27 November 1829 he assigned his one-third share in the Literary Gazette to Longmans for £1000; this was part of a complex arrangement negotiated with Twinings, to whom Jerdan owed a considerable sum, and Roby who held his insurance policy. Jerdan agreed to pay interest to Longmans at two pounds per cent per annum on a quarterly basis, and if he failed to pay it, Longmans was authorized to withhold it from monies due to him as Editor (Longmans Archive, II 129/8. University of Reading, Special Collections).

Despite grumbling about the volume of work he was getting through, Jerdan seemed to thrive on it. “Activity of mind seems to grow with the utmost stretch of employment” he remarked, continuing with the memory that “The Literary Gazette gave me incessant occupation, I may say night and day. On returning from the gayest party, I was usually at my books and desk writing for reviews, or scribbling down some disjuncta membra to remind me of passing original thoughts. To use a much-abused phrase, my imagination was much more ‘suggestive’ in post-prandial and nocturnal than in breakfasting and matitudinal hours” (4.246). Here, he lightly touched upon the subject for which he was most noted in contemporary memoirs, that of a man who enjoyed a bottle or two, but for Jerdan the stimulation gained from partying was the lubricant he needed to accomplish his work. Then to be productive, “to enjoy the needful quietude and sedateness, the busy world must be shut out and asleep, and then you may glide from all the philosophies of letters and life, to revel in stranger abstractions and the fantastic delirium of dreamland. Castles in the air are delicious buildings; unreal? No! they are real cities, temples, sanctuaries of refuge from the cares, the troubles, the anxieties of the material lump-world.” Small wonder that Jerdan, with all his professional, domestic and extra-curricular cares, welcomed the “fantastic delirium of dreamland”.

Given his concerns, it was remarkable that Jerdan’s interests were far wider than solely the promulgation and review of literature; his active interest in the Royal Society of Literature and the Literary Fund were part and parcel of his primary focus, but he also used the Literary Gazette as an instrument to lay the foundation for the (later Royal) Geographical Society. The seed had been sown in the issue of 24 May 1828 when, responding to a letter from ‘A.C.C.’ identified later as Thomas Watts, a clerk or librarian in the India House, he agreed that a Geographical Society “would be an excellent institution in England…It is a great desideratum among our literary and scientific associations...it only needs three or four active and influential persons to originate such a plan. We trust to see this matter taken up by efficient hands” (4.405). “From the egg thus dropt”, said Jerdan, “the Royal Geographical Society was hatched” (4.267). He received, and published on 20th September, a letter from W. Huttman, of the Asiatic Society, enthusiastically supporting and elaborating the idea. More than a year passed, during which meetings were held by Huttman, with John Britton, Jerdan, and a few others, a Captain, a Colonel and a Lieutenant. Eventually, after their various deliberations, Jerdan received an uncorrected proof of a Prospectus, which he published in the Literary Gazette of 8 May 1830. Jerdan made some amendment to the prospectus which mentioned only Britton’s name. This was then printed and circulated amongst interested parties. Jerdan reprinted this Prospectus in the Appendix to Volume IV of his Autobiography, plainly delighted to have had such an influential part in the establishment of an august institution.

Understandably keen for his journal to take full credit for initiating such an important new Society so in keeping with the exploring and discovering spirit of the age, Jerdan wrote again in the Literary Gazette:

We are happy to see the suggestions, first promulgated in the Literary Gazette, respecting the formation of a Geographical Society in London, at length so highly and powerfully adopted as to leave no doubt either as to the formation of such an Institution, or as to its efficiency. In England we move slowly – perhaps, but if the cause be good, perhaps not the less surely. The hints we have thrown out during the last two years did not immediately fructify, but they made their impression; or, not to spoil our metaphor, they took root; and when we lately intimated that they were about to produce the desired return, the statement seems to have stimulated those most competent to realise the harvest into the activity which was, alone, requisite to the occasion.

In the summer of 1830 a meeting occurred at the Raleigh (Travelling Club) where Captain Smyth proposed his own draft prospectus. John (afterwards Sir John) Barrow, Secretary of the Admiralty, was in the chair, and resolutions were agreed for the establishment of a Geographical Society. Britton sent the rival prospectus to Jerdan who saw its marked similarities to his own draft. He “confessed to a feeling of mortification at the supercession of the plan at which he and his friends had been working for two years, but he made the best of the situation.” Formally invited to become a Member of the Society, Jerdan wrote to Barrow on 10 June:

I am very much obliged by the Prospectus of the Geographic Society, which being first suggested in the Literary Gazette is naturally a favourite with me. I should be proud of the honour of being a Member of the Society; and happy to promote its interests by every means in my power, tho’ with such names as I now see associated with it, and under such influence as yours, it can need very little from the humble efforts of an individual like me. [Records of the Royal Geographical Society CB1/28]

Jerdan did as he promised, and kept the public informed about the Geographical Society through the columns of his magazine. The consequence of this publicity, Jerdan claimed, was that “above five hundred adhesions were announced of noblemen and gentleman of distinction in life and literature, such as I never knew combined before at the commencement of any undertaking of any kind…” Before the end of the season Lord Goderich (Earl of Ripon and lately Prime Minister) “was elected President, and the Society entered fairly and fully upon the career of its imperial usefulness…somewhat in loco parentis, I take a papa’s pride in believing that it is at the present day in as flourishing and beneficial a condition as ever it was at any preceding date” (4.272). In February, probably of the following year, he wrote again to Barrow, offering the services of a correspondent who wished to travel in Paraguay and was seeking a grant for the purpose. There was no suggestion of this approach being of any financial advantage to himself, so it would seem to be another instance of Jerdan’s kindness in using his network to help anyone who needed assistance. Although one of the original Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society, Jerdan took on no official role, but retained a great interest in the Society throughout his life.

Neither the Literary Gazette nor the Athenæum, in common with other similar journals of the time, named their reviewers. In the Literary Gazette the leading reviews were likely to have been largely written by Jerdan himself, assisted by L.E.L., although it is probable that her input was in poetry reviews rather than prose. As far as the Literary Gazette’s rival, the Athenæum was concerned, its editor Charles Dilke insisted not only on anonymity in the printed publication, but he also “never signed anything that he himself wrote, and he carefully refrained from putting the names of reviewers of books written by members of the Athenæum staff in the marked office file” (Marchand 106n). Jerdan’s failure to keep an office file at all avoided this difficulty. (Unfortunately, it was an omission which now renders it impossible to identify many contributors with certainty.) Dilke’s insistence on impartiality was of a piece with the highly moral stance for which the Athenæum had, by this time, become well known; it was, however, at odds with the practices common in journals which had business links with publishers, like the Literary Gazette, the New Monthly Magazine, Court Journal and United Services Journal, all part of Henry Colburn’s stable. Dilke pursued this moral stance to an obsessive degree, even demonstrating a “reluctance to go into society in order to avoid making literary acquaintances” (Marchand 98). What a contrast to the excessively sociable editor of the Literary Gazette, for whom society in all its forms provided the materials and enthusiasm for his work and even, it may be said, for his life.

Decisions whether or not to review works by friends and colleagues was of a different order from decisions about reviewing works published by those with a financial interest in the journal, making the “reviews” look like impartial criticism, when they were in fact paid paragraphs. This was the “puffing” that the Athenæum so despised, and of which Jerdan had been so violently accused – notably by Westmacott, and again in the pages of the Athenæum. The latter made the charge very openly on 29 October 1831: “The deceptive influence, against which the public should be put on their guard, is that of book publishers; we have no doubt, that if Mr Watts will examine five hundred columns of reviews in the Literary Gazette, one half will be found filled with the praise of works published by Colburn” (705; quoted 109).

From this distance in time it could be suggested that frequent mention of the works emanating from Colburn’s publishing house was almost unavoidable. The Literary Gazette was aimed at the middle-class family, whose taste in fiction was, at this period, for the ‘silver-fork’ school in which Colburn specialised. It has been pointed out, in fact, that “It is hardly an exaggeration to say that nine-tenths of the fashionable novels bear the colophon of Henry Colburn” (Rosa quoted Marchand 109). Colburn’s list for 1828 showed sixty-five new books in addition to his back list (Marchand 111). His authors included Hazlitt, Disraeli, Hook and Bulwer. Therefore, if Jerdan had refused to review the output of Colburn’s silver-fork fiction and the flood of other novels under this publisher’s imprint in order to avoid the charge of partiality, the Literary Gazette could have been accused to failing to review the popular fiction of the day. Jerdan was between a rock and a hard place. In England and the English (2833) Edward Bulwer stood up for Jerdan, although without naming him, claiming that as far as Colburn was concerned,

it was a matter of the most rankling complaint in his mind, that the editor of the journal, (who had an equal share himself in the journal, and could not be removed), was so anxious not to deserve the reproach as to be unduly harsh to the books he was accused of unduly favouring…I certainly calculated that a greater proportion of books belonging to the bookseller in question had been severely treated than was consistent with the ratio of praise and censure accorded to the works appertaining to any other publisher. [Quoted Lawford]

However, it has been noted that “the majority of readers of the New Monthly or the Literary Gazette and newspaper ‘paid paragraphs’ accepted the judgments as opinions of impartial critics of literature.” There were occasional exceptions: in the issue of 30 January 1830 appears a notice of a book published by Colburn and Bentley. Random Records deserves a random review and these volumes are not entitled to more than desultory notice”. In the same issue, Adventures of an Irish Gentleman, also published by Colburn and Bentley, was harshly reviewed: “The ‘adventures’ are improbable and absurd, as well as coarse and of a style and school quite departed, as the Americans say, ‘slick right away’.”

The Court Journal, (the reincarnated London Weekly Review) another of Colburn’s publications, had revealed that a novel by Lady Charlotte Bury, published by Colburn, was a revision of another book which had appeared fifteen or twenty years earlier. The Literary Gazette defended Colburn & Bentley, asserting that they did not know of this deception. The Athenæum was delighted to have a real target:

‘We are convinced’, says the Editor of the Literary Gazette, ‘that Mr Colburn must have been unconscious of this trick, for we find the following preparatory announcement in the New Monthly Magazine for August, which is also his publication and would not have sanctioned the utterance of such a paragraph had he been aware of the truth.’ Here is the admission of the Editor of the Literary Gazette that Mr Colburn is in the habit of sanctioning and approving (of inserting, for that is the plain English), paragraphs in his own papers and the newspapers which are so worded as to pass for the honest judgment of the Editor of the work; - and the Editor of the Literary Gazette speaks with authority, seeing that Colburn is a large shareholder in his own paper.

Jerdan could not win, at the behest of such a man as Colburn.

The other side of the puffing coin was one that did not directly involve Jerdan and the other editors at all, but was crucial to the publishers. They, and most notably Colburn, used their skill in advertising books to tempt authors to choose them above rival publishers to produce their works. Reputedly, around 1830 Colburn was spending on average, £9000 a year on advertising (Collins). Advertisements containing excellent reviews, whether ‘puffed’ or genuine, might persuade a potential best-seller writer to select one house over another. Colburn had a reputation for paying high prices and achieving substantial sales, benefits which, for writers, overcame his other reputation for “unsavoury or at least undignified methods of advertising (which) grew into something of a byword in the trade” (Marchand 112). Jerdan fought back.

In a rare example of writing a Leader or Editorial for the Literary Gazette, Jerdan used his journal’s front page and half a column of the next, on 17 April 1830, for an article he called ‘The Cut-and-Dry System of Criticism!’ It is a method, he pronounced, “growing into great force and magnitude, is individually and patriotically odious in our eyes. It affects us and it injures literature: it is founded on selfish motives and abuses the public mind.” The practice referred to was the selection of twenty or so striking passages from a book about to be published, made by the writer or the publisher. These extracts were printed on to a separate sheet and sent out with review copies of the book to newspapers and magazines. The reviewer was thus relieved of the task of reading the book, but could merely quote from the suggested passages. Jerdan acknowledged his ingratitude in exposing this “cut-and-dry” method, which was designed to make his, and other reviewers’ lives easier. He noted ironically that they were not only saved from “wading through lots of dulness and trash”, but the system also put reviewers on excellent terms with authors and publishers, as they just had to praise them and give the selected extracts, thereby avoiding the abuse often hurled at them for not praising enough. Even remote provincial journals could thus be reached by publishers, resulting in the rapid spread of unanimous good opinion of the cut-and-dry promoted books. The consequences of this abysmal practice, said Jerdan, are “humbug and imposition”. The public were gulled into buying, were disappointed, felt cheated, until the next reviews, when the cycle started again.

This was merely the tip of the iceberg. “The great wrong lies deeper”, he declared. “It is by the protrusion of what is worthless that real merit and talent are stifled. The voice of modest Genius cannot be heard amid the din of clamorous puffing…” Jerdan believed, furthermore, that the practice of cut-and-dry had a deleterious effect upon the national literature, because learned volumes, beautifully produced poetry and original research, were too expensive for publishers to produce good quality for a limited number of readers, whereas the Circulating Libraries bought quantities of “the ephemermides of the hour, which, by being puffed into notoriety, attract the multitude, are disposed of, repay the outlay, disgrace our literature, deprave the public taste, and are forgotten.” The newspapers were devoted mainly to political news and were content to fill their other columns with paid paragraphs and advertising, the one ensuring the other, so that all newspapers were alike, because they used the same material. The Literary Gazette, promised Jerdan, would “adhere to the opposite course…and deliver its own opinions”. He pointed out that the practice he abhorred was so widespread, no personal allusions had been made. “If the English reader wants a book calculated for future times, he must go to Germany, or France or Russia! For in England there are nothing but reprints, compilations, annuals, periodicals and the old species of machinery of the druggists’ bottles mingling the contents of several and shewing off the mixtures of every colour of the rainbow”. His readers would now recognize the “cut-and-dry” method, and know that such reviews were “not the dicta of literary independence and justice.” This was a startling and daring article, and Jerdan was taking a considerable risk. A large part of the Literary Gazette’s income emanated from the pages of advertising for new books and annuals, as well as the compilations of which he complained. To risk cutting off the hands which fed his journal, he would have had to feel very strongly on the matter, which, as well as an attack on publishers in general, was a more specific attack on Colburn, whose puffing activities were notorious. Such a serious and responsible attitude to his profession belies the story told of Jerdan that he cut the pages of a book and smelled the paper knife for matter on which to base a review (Rosa 204).

The charge of puffery was one that continued to bedevil Jerdan. George Whittaker threatened him with withdrawing advertising in the Literary Gazette unless reviews of his works improved, even though he maintained that sales would remain the same with good or bad reviews. This was a threat to be taken seriously, as Whittaker’s publishing house was second only to Longmans in the number of new titles listed in the English Catalogue of Books for this period. When he was thirty years old in 1823 Whittaker had been elected sheriff of London and Middlesex, so was a man who wielded some considerable clout in many circles and it took courage to stand up to him. Jerdan protested to Cosmo Orme, a partner in Longmans, that nine of the ten reviews of Whittaker’s works in the previous month had been favourable, and that “It is utterly impossible to produce a review which shall always be puffing: and every person of common sense must feel that individual pretensions…must be contemned if we mean to cultivate an honest reputation with the general reader” (4.22). Jerdan followed this up with a spirited response to Whittaker himself: “be assured that indiscriminate praise is not the course to serve any publisher; at any rate, I will not sacrifice my independence and integrity by making the Gazette its organ...I will not give up one jot of its fairness, impartiality or justice, to conciliate all the publishers in London.” (An examination of the ten reviews disclosed “that of the nine works Jerdan claimed had received ‘praise’, five were met with qualifications which would have made buyers hesitate and booksellers, who expected enthusiastic puffs, uneasy” Duncan 74) In his Autobiography Jerdan offered his correspondence with Whittaker as proof of his clear intention to keep the Literary Gazette impartial. To do so, he had to fight not only outside publishers, but also his own partners, a heroic but ultimately impossible task. In self-defence he wrote:

In vindicating the Gazette from the aspersions with which it was so insidiously assailed and misrepresented, till a pretty general belief was obtained for the falsehoods, I do not mean to say that it, or any journal of its class, can be carried on with perfect freedom, and uninfluenced by any circumstances. On the contrary, personal regards and attachments, literary connections, and friendly interferences must have an effect in enhancing praise, and moderating blame; and, in a baser manner, rivalry, envy, and malignity will, in some instances, have the opposite effect in producing damning faint praise, or undue commendation, and abusive censure. To the former I plead very partially guilty – the latter I utterly repudiate and deny. I never penned a malevolent article during the whole of my long career; and, to the best of my knowledge, I never concealed or perverted a truth, even when noticing the performances of those I knew to be my unscrupulous enemies. [4.82]

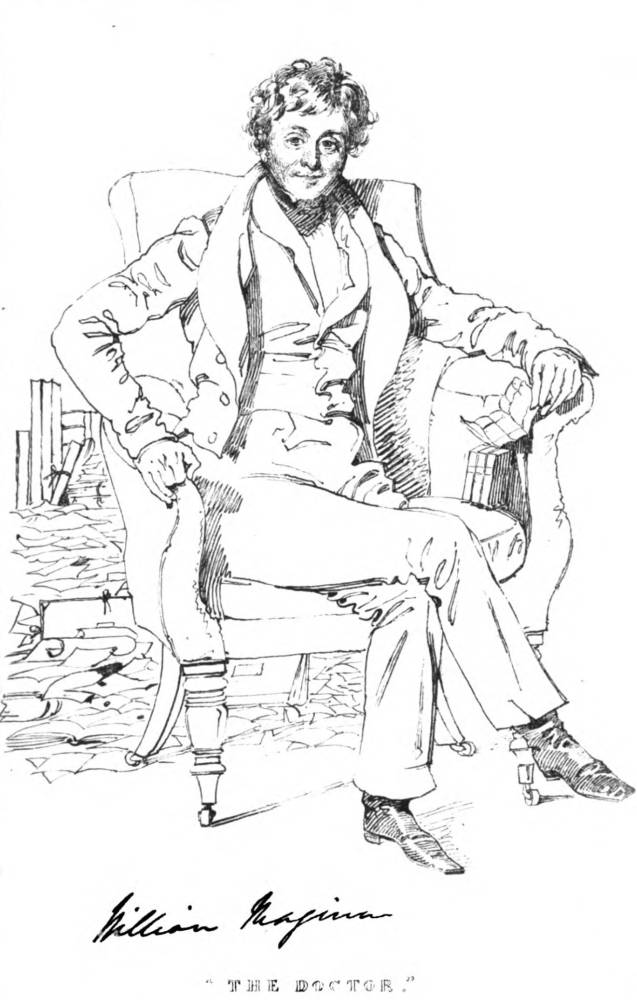

William Maginn by Daniel Maclise from Jerdan’s National Portrait Gallery.

Despite his best endeavours to maintain high principles, he was still perceived as the publishers’ hack, leading him to protest “I do not believe that any periodical and its editor were ever exposed to the industrious circulation of systematic falsehood in a greater degree than the Literary Gazette and myself for many years” (4.24). There is a degree of naivety in his protestations: the practice of puffing was expected by the publishers, and compliance was a form of mutual back-scratching. In return, journal editors were favoured with early copies of books for review. William Maginn, editor of Fraser’s magazine wrote to Jerdan in 1825, “I write to you – for there is no use of talking humbug – to ask you for a favourable critique, or a puff, or any other thing of the kind – the word being no matter...You will oblige me by giving it a favourable and early review in your ‘Gazette’” (4.102). Maginn may have been squeamish about using the ‘puffing’ word, but his request was clear.

Jerdan had an almost impossible task in struggling to keep the Literary Gazette impartial. Colburn was remorseless in demands to ‘puff’ the books he published, and became so synonymous with the practice that jokes and jibes at his expense appeared in the popular press, and were encouraged by writers who were not part of his stable. Commercial rivalry and professional jealousy would be primary motivators for such attacks, as well as a fairly universal dislike of Colburn’s self-promoting personality. Dilke’s Athenæum was in the forefront of fighting the practice of puffery, and the target of Dilke’s opening barrage was the ‘Juvenile Library’ published by Colburn and Bentley.

Only a month after the demise of the ill-fated Foreign Literary Gazette, Colburn and Bentley came up with a plan. Seeing the success of a series of good works in cheap editions pioneered a few years earlier by Constable’s ‘Miscellany of Original and Selected Publications’, they proposed to publish four distinct series of their own. A printed Prospectus for ‘The Library of Modern Travels, Voyages and Discoveries’ did not proceed past the planning stage; ‘The Standard Novels’, “a reprint series, was profitable enough to appear from 1831 into the 60s. A third series, ‘The National Library’ “produced seven original books in late 1830 and early 1831, before harsh but well-deserved reviews halted it” (Pyle 189). The fourth in the proposed series was the ‘Juvenile Library’.

Jerdan worked hard, producing a four-page list of suggestions for this project, the puffing of which were to cause the Athenæum such fury. His suggested subjects ranged from a History of Christianity including the Accounts of Massacres and Martyrdoms, to Dress and Costume, the Medici, a History of Trees, and many other topics. He slipped in a line for “Jerdan’s Cyclopaedia” to be 24 volumes, commencing two years hence. He also suggested a few possible writers, including Mrs Hofland, Miss Edgeworth and Bulwer. It has been noted that “Jerdan’s selection of authors was safe, for he took the easy course of engaging writers who had contributed to other serial works” (Gettman 40). It seems natural that he would indeed choose authors who had a proven track record, and whose names would be well enough known to attract the buying public to the new series. Jerdan mentioned his ideas to a few people who thought well of the plan.

In 29 April 1830 he drafted a Memorandum of Agreement in a letter to R. Bentley, asking for three hundred pounds per annum — which is overwritten as £200 — for twelve volumes, twenty-five pounds for any extra volumes, and fifty pounds extra per annum for the sale of every thousand copies above four thousand. The agreement to be for one hundred volumes (i.e. over eight years’ work), to be continued thereafter by mutual consent or, if unsuccessful, to be discontinued after twenty volumes. His draft stated, “The discretion in the choice of subjects and writers to be vested in the Editor”. He wished to clarify payments to his writers at one hundred pounds per volume for eight, and seventy-five pounds per volume for four within the year, anything larger to be agreed with Colburn and Bentley. He substantiated his suggestion of three hundred pounds per annum, saying that twenty-five pounds per volume was a fair price. “I have the same for writing 24 pages of the National Gallery, which has risen in thousands within the five months of my superintendance, the labour of the Library must be much more – infinitely more.” He assured Colburn and Bentley that “writers will make fairest bargains with me than with you. They will press less greedily.” On payments, he may pay some fifty pounds, others one hundred and fifty pounds, but the total would remain as agreed. Jerdan urged that the project be started at once, and that writers should be engaged for the first twelve to fifteen volumes. To hasten their decision he told them that Mr Whittaker (of the rival publishing house) had been to see him, and had agreed to abandon his plan for a similar Library in favour of Jerdan’s.

The following day, 30 April 1830, a revised contract was drawn up between Jerdan and Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley Publishers of New Burlington Street (British Library. Add.MSS.46611 f.137). Jerdan was to “edit, revise and prepare the said work for publication in the most careful manner” and to acquire the best writers on reasonable terms, and promote the sale of the work. His remuneration was that “so long as the work shall be regularly published and continued at one volume per month” Jerdan would receive three hundred pounds per annum. Should any monthly part reach sales of five thousand copies (this revision increased the original suggestion by one thousand copies per month), Jerdan’s salary would rise to three hundred and fifty pounds per annum, and so on, adding fifty pounds per annum for every additional thousand copies sold monthly. Colburn and Bentley agreed to the extra twenty-five pounds to edit and prepare any additional volumes. A clause that underwent a fundamental change was the one which stated “The choice of subjects and the writers and the sums to be paid to them to be mutually agreed upon between the said parties – that is to say neither party to be at liberty to enforce the writing purchases or publication of any work against the reasonable advice of the others.” Jerdan was thus kept in tight control under the thumb of the publishers, who further inserted into their contract a clause to the effect that “the work to be continued only so long as the said Colburn and Bentley find it sufficiently advantageous to them to do so” differing again from Jerdan’s original suggestion of a minimum of twenty volumes, and a rethink after one hundred. No security then for Jerdan, who was under enormous pressure to perform well in this new project, in addition to his already arduous duties on the Literary Gazette. A postcript to the contract noted that Bentley and Colburn “will not object to the sum of from Fifty to One hundred pounds per volume being given when the interest of the Work and the influence of the writers shall warrant the same”, again taking from Jerdan control of what was paid to an individual writer.

The several changes to his draft agreement, all reducing his control and power over subjects and writers, drew an angry letter from Jerdan to Bentley on 1 May 1830. So indignant was he at the lack of trust, that he declined the editorship of the Juvenile Library, explaining carefully that it was specifically the fourth clause to which he objected, the one in which there was to be mutual agreement over writers, subjects, and fees. Jerdan’s letter is the clearest contemporary surviving statement of his professionalism, his self-esteem and self-confidence in his editorial abilities. He may justifiably have been outraged by the cavalier treatment of his potential employers; he had, after all, been associated with Colburn for better or worse, for the previous thirteen years, and felt that his credentials had been impugned: “Upon the editing of this work I must stake my whole literary credit...” Under the redrawn terms Colburn and Bentley could end the Library, and Jerdan’s employment in it, at any time; it was thus obviously in his own interest, Jerdan pointed out, to put in the work necessary to ensure its success. “I therefore hold myself entitled to the whole trust and to your perfect confidence, in the selection of works and writers.” In addition – and this was brave, considering Colburn’s monopoly of the popular market for fiction – Jerdan continued: “I should desire to keep myself distinct from your particular class of writers, without meaning the slightest disrespect to them...to be monthly discussing which is best or worst would I fear led to misunderstandings, and I cannot go on with a work unless I give my heart and soul to it in my own way.” He went on to insist that he should pay what he saw as necessary to specific writers as long as the total did not exceed the sum agreed. He demanded that his would-be employers look “to me and not to my means for the proper execution of my work.” If the scheme did not work, he wrote, he would step down, with six months’ notice on either side. Tacitly acknowledging his bad record with figures, he concluded, “The simplification of operations and accounts the whole being reduced to twelve entries per annum is a powerful recommendation of the task.”

That Colburn and Bentley finally agreed to his terms seems apparent, as within a very short time, a scant two months, the first issue of the ‘Juvenile Library’ was published. This was Lives of Remarkable Youth of Both Sexes, by D.S.Williams and Don J. Telesforo de Trueba y Cosio, the first of two volumes. It seems to have been a case of ‘more haste less speed’. Jerdan’s letter of 29 June 1830 told Richard Bentley that he was “much chagrined to see a Volume so full of errors as the first of the Juvenile Library to go forth to the world as sanctioned by me, and I certainly cannot permit my name to be so abused”. He also objected to the price being raised from three shillings and sixpence to four shillings. Prophetically, he remarked “I am not a grumbler, but we must proceed fairly together, with a good understanding, or evil will come of it.” For once, the Athenæum agreed with him, declaring, “we do not know how the young of both sexes could be better employed, for the improvement of their minds, than in correcting the sentences in the first volume of the Juvenile Library” (Quoted Gettman 40).

The Literary Gazette of 26 June 1830 noted the arrival of the new volume, but had not time to review it. The “puff” highlighted the four portraits and suggested the book as a “holyday gift”. The following week it reluctantly reviewed the book. Sensitive to the ongoing accusations of ‘puffing’ the reviewer claimed to be embarrassed as to how to deal with the book. If he wished to dispraise it, that “would be an effort of stern virtue scarcely to be expected from human nature; to eulogise it, however deserving we may consider it of eulogium, would be inevitably to expose ourselves to the sneers and ridicule of all our ‘good-natured friends’; entirely to abstain from noticing it, would be signally to fail in our duty both to the public and the publishers.” He compromised by letting the book speak for itself, and selecting one life of the nine lives it contained and quoting the extract in full over about one and a half pages. There is also a comment that three thousand copies were ‘disposed of’ on the first day the book appeared. The ‘review’ ended by promising a further extract from one of the other lives in the next issue of the Literary Gazette. In the same issue, under the heading ‘To Our Correspondents’, Jerdan proclaimed that

Our review of this work, to a certain degree explains the difficulty of our position with regard to it;…the volume was submitted for criticism to a gentleman as independent of the Literary Gazette as the Literary Gazette is itself independent. A man of firmness, talent and integrity, he was assured that our invariable rule was to know neither friend nor adversary in these pages; and that therefore he should exercise in this and every similar case, his unbiased judgment.

This declaration conflicts somewhat with the “embarrassment” mentioned by the reviewer, but it served to bring the ‘Juvenile Library’ to the notice of the reader once again. In all, it received six mentions in the Literary Gazette; Jerdan was clearly not so embarrassed that he did not make full use of his position to promote this project of his own, at a time when the death of King George IV, briefly mentioned under ‘Politics’ in the stamped edition of the Literary Gazette was likely to be uppermost in the minds of his readers, together with the accession of his sixty-five year old brother, William IV.

The second volume in the new series was Samuel Carter Hall’s Historic Anecdotes of France. Hall recollected how Jerdan, in a state of harassed apprehension, came to him on the ninth day of a month and explained that a history of France promised for the first day of the next month was not forthcoming. Jerdan declared that it was a case of producing the book or closing the series, and he asked Hall to undertake the task. Agreeing to do so, Hall spent one day surrounding himself with a hundred books on France. He then had only eighteen days in which to produce a book of four hundred pages. During one stretch of twelve days he never went to bed, and the result was “a brain-fever” and a wretched book. Hall naïvely concluded: ‘it is somewhat strange that Jerdan in his Autobiography has made no mention of this series, or of his engagement with Colburn and Bentley, as its editor’” (Retrospect 1.312) There is no reason to doubt Hall’s account of the pressure Jerdan put him under, although his concluding remark is inaccurate. He was by then a man of eighty-three years old, recalling events of several decades earlier.

Learning from past experience, Jerdan took his time producing the third volume of the ‘Juvenile Library’, which appeared on 4 October 1830. It was by Miss Jane Webb (later introduced by Jerdan to C. Loudon, writer on landscape gardening, whom she married. Her contribution was titled Africa: its History. Sending Jerdan the concluding pages, Jane Webb told him that Colburn had advanced her ten pounds three weeks earlier, but the money was now gone. She had written two or three times to Bentley. “He however is not as fascinating as the dear little man for he has never replied to my letters” (Bodleian Library MS. Eng. lett. d. 114, f300). The Examiner, which devoted several columns to extracts from the book, was vicious about its editor: “We know not…why the instruction of little folks must be superintended by Mr Jerdan, who knows nothing, little or great”; and went on to point out grammatical errors which had slipped past his notice. The Athenæum remarked meanly that Africa was “in a less pretending style than that of its melancholy predecessors”, hinted at hostility between Jerdan and his publishers, and concluded “it is not very improbable but that this juvenile expedition to the Timbuctoo of knowledge may utterly perish in Africa” (23 October 1830). They were right. The ‘Juvenile Library’ was not a success. In desperation, Jerdan wrote to Bentley at the beginning of October

I think you are not truly keeping faith with me respecting the Juvenile Library; but on the contrary are sacrificing it to the National Series. After what we agreed to I could not expect that you would depreciate this work by statements that it was to be immediately dropt, as has been done to Mrs Hall – rumours of this kind leave no fair chance for the publication, and are very painful as well as injurious to me – my name and literary character being made mere sports of on the occasion. I think it only right to let you know my sentiments on this business in which I embarked at your own pressing instance and through which you are in honour bound to hear me respectably.

Money was always an issue with Jerdan. He had agreed to pay seventy-five pounds to the writer of the fourth volume, Greece, due in November, and asked Bentley for a cheque to cover this. He again had to write to Bentley telling him that he was “obliged to anticipate fifty guineas at Messrs. Longmans in order to meet my draft on Drummonds tomorrow on account of the Juvenile Library. I think it is very hard.” Another note, written with great urgency, instructing the bearer to wait for a reply, asked Bentley for a ‘note’ of fifty pounds payable in two months, to cover the next two volumes of the Juvenile editorship; his reason was that he in turn was having to give advances to writers and was “dry as a chip” for a few days (Ransom). Dated only ‘Monday night’ and annotated 1830, another letter from Jerdan to Bentley referred to money, but also to another matter which is now not clear. This may have referred to L.E.L., Dr Thomson being her physician and friend. It read:

I am much obliged by your letter and exceedingly vexed that we should correspond on so unpleasant a subject. I fear the real gist of the matter is evaded, or not seen in what has been done. From Dr Thomson’s I have the most degrading representations – it is (myself out of the question) the most vexatious thing that could occur for the credit of C & B – All that I shall do is to clear myself – I am no beggar off of engagements and I dread being held up even by the worst of periodicals in so miserable a light …I have today borrowed money again to give for the honour of the concern, while much put about myself. I hope to hear tomorrow, but after the delays I have seen, will proceed as declared.

He added, squeezed into a corner, “I had not room to sign W. Jerdan but I shall not allow another day to pass without taking steps to set myself right with all concerned.”

Far from puffing the new project as he was widely accused of doing with all his productions, Colburn was, in Jerdan’s estimation, “liberally damning it”. Jerdan informed Bentley that he would be “glad to release you from an undertaking prosecuted with so little cordiality.” Two weeks later the relationship between Jerdan and the publishers had deteriorated to the point of no return. Jerdan claimed to have put his own feelings aside, in the matter of the ‘Juvenile Library’, only to find that Colburn and Bentley had gone behind his back, trying to negotiate secretly and separately with the writers with whom he had already made arrangements. Speaking of his “disappointment and mortification” Jerdan protested vehemently that all his own efforts had been counteracted and that

you seem bent on incurring the evils pecuniary and literary I have been so anxious to prevent by very fruitless, and I think not very creditable or high-spirited negociations with each in their turn. You will find this fail, and you are provoking hostilities of the most irritating and injurious kind. Cost in the end, and public attacks upon your characters to boot are inevitable….my position appears to be utterly forgotten, and every individual whom I have engaged with to write is treated separately in a manner I deeply disapprove, and without reference to what has passed between them and me – placing me in a light so ridiculous and contemptible that I neither can nor will endure.

A scrawled list in Jerdan’s handwriting probably relates to the commissions he handed out for the ‘Juvenile Library’. His ‘Absolute’ list of five writers totalled £375; the second group of four, “may be stopped at (say £25)”, and included Landon; the third, six writers who should share £100 between them. The total owed was £534. A few more names came under the heading ‘Doubtful’.

To salvage what he could from the impossible situation Jerdan offered Colburn and Bentley “more in pity than in anger” a choice of two courses: one, that for five hundred pounds he would continue his original negotiations, and take any claims upon himself; alternatively, that he would send all writers a circular letter (a copy of which he enclosed for their information) absolving himself from all responsibility and informing the writers that they were now answerable to Colburn and Bentley directly. This would cost them far more: “I believe that £1000 and much odium must be the price and result of this alternative.” He gave them the weekend to make up their minds. The note which he appended to the copy of his letter circulated to the writers, announced that they chose the second option, and “I have therefore to request you will not proceed farther with the work you engaged to write, but furnish them with the amount of your demand for what you may have done, which they have assured me will be immediately and honourably discharged.” They were possibly not quite as immediate as they promised: in December Jerdan received a request from his friend James Robinson Planché for a formal letter stating that he had been engaged to write a volume on Costume for the Juvenile Library for a fee of one hundred pounds, confirming that this had been sanctioned by Colburn and Bentley, together with ten similar engagements. The possibility of a second volume had not been discussed with the publishers. Had the publishers paid their debts on time, Planché would not have needed this formality from Jerdan.

Barely on speaking terms with his publishers, Jerdan’s eyes and ears at New Burlington Street were those of Charles Ollier, the partners’ general assistant, who drew up a list of works in progress when the ‘Juvenile Library’ was abandoned (Gettman 39). This named titles and authors, with a note of the status of each work. It corroborated the letter Jerdan wrote to Bentley asking for seventy-five pounds for the manuscript of a History of the Children of Israel for which he held the writer’s discharge, noting “besides a further advance”. The list itemised which works were “in progress”, “nearly complete”, or “hardly begun”, and stated that Planché’s work on Dress, which they were slow to remunerate, was in a state of “considerable progress.” Planché sued Colburn for failure to accept and pay for his commissioned work, and won. According to a report in the Athenæum of 25 June 1831, Jerdan said he thought that Planché and the other writers would have accepted twenty-five pounds because they were his personal friends, and “he had the power of obliging them.” The Athenæum believed they were each due double that amount, but the journal had every reason to belittle their rival, Jerdan. On the other hand, the writers were Jerdan’s friends, and he may well have made such an ill-considered statement, to rile Colburn. The Times was more objective, stating that Jerdan had contracted to pay one hundred guineas for the volume, and thought fifty pounds only a fair remuneration for his trouble. “He had never said £25 was sufficient. A paper was, however, produced in Mr Jerdan’s writing”, saying that Planché and others might be satisfied with one hundred pounds between them. “Mr Jerdan said this was on the footing of an arrangement personally with himself, as friend of the parties, but he thought the plaintiff’s claim against the booksellers, of £50 was quite fair” (The Times, 15 June 1831).

Jerdan and his writers were not the only ones to lose by the abandonment of the ‘Juvenile Library’. According to Gettman(42), Colburn and Bentley bore a financial loss, as itemised in this statement of the project amongst the Bentley papers which also shows how quickly sales declined with each volume produced:

| Jerdan editing | £125 | sale no. 1 3300 | |

| Copyrights | 400 | sale no. 2 2000 | |

| Advertising | 500 | sale no. 3 1300 | |

| Illustration | 250 | 6600 | |

| Binding | 180 | stock 3600 | |

| Printing | 180 | £1035 | |

| Paper | 300 | Loss £ 900 |

If Jerdan’s claim that the first volume sold three thousand on the first day is true, then the additional three hundred indicates the poor reception of the book once it was in circulation. Jerdan’s dissatisfaction seems to have been only with Colburn, as he wrote to Bentley that he believed it was not his fault things had gone so badly wrong, and he would not add another complaint to all the unpleasantness which the publisher must be experiencing. Jerdan mentioned that he had already been censured for the debacle “in a high quarter”. Colburn tried to make Bentley pay two hundred pounds for three books intended for the Juvenile Library, a claim Bentley stoutly refuted. Three other books were salvaged and published later (Gettman 43).

Jerdan’s only reference to this fiasco in his four-volume Autobiography was in the concluding chapter of Volume Four, indicating either its insignificance to him or, more likely, that over twenty years later he was still so hurt by the treatment he had received he could hardly bear to mention it. “after some progress”, he recalled, “the design was abandoned by the publishers; in consequence of which several annoying disputes arose between them and the contributors, led to considerable expense, and vexed me extremely…it is yet an excellent plan, and might be carried into effect” (4.376)

Abandonment of the project was hardly surprising in the light of the Athenæum’s attack on the puffing Colburn lavished upon it. The issue of 17 July 1830 sneered:

No-one will have the hardihood to say that the ‘Juvenile Library’ is not become a positive nuisance in the newspapers; for it is scarcely possible to get through a single column of Chronicle or Herald without having to suffer a Burlington Street paragraph. Nothing can be so moral and edifying as the 'Juvenile Library'; nothing so pure and pleasant as its style; nothing so disinterested and generous as its object. The paragraphs, which are paid for, say all this;

(This accusation is at odds with Jerdan’s perception that Colburn was ‘liberally damning’ the project, but perhaps the ‘damning’ was merely verbal to those in Colburn’s circle.) The Athenæum and, in Jerdan’s eyes at least, the Literary Gazette set out to bring literature into public notice and encourage readers. However, for Colburn and others like him a book was a commodity to be advertised and regarded no differently from boot polish or potatoes. It was this mercantile approach and the onslaught of advertising, as well as its poor opinion of the ‘Juvenile Library’, that goaded the Athenæumon July 17 1830 into complaining: “It is the duty of an independent journal to protect as far as possible the credulous, confiding and unwary, from the wily arts of the insidious advertiser. And as we honestly think that the ‘Juvenile Library’, judging it from the volume before us, is a hasty, pretending, ill-written work… we hold it right to strike out of the path which our contemporaries have pursued, and to devote to it a candid column instead of a paid paragraph” (440 quoted Marchand 125). Three weeks later on August 7, 1830 it referred again to “one of the most hasty, inaccurate and contemptible books ever published – the first number of the ‘Juvenile Library’ (491). Unsurprisingly, Colburn withdrew his advertising for the ‘Juvenile Library’ from the Athenæum. When the fledgling project failed, the Athenæum jibed: “By the bye, we have not seen even one little pleasant paragraph paying gentleman-usher to the third volume of the ‘Juvenile’.” Jerdan’s hope of extra income had died with it.

The Athenæum now had the bit firmly between its teeth, and regularly attacked the practice of puffery. Although its ire was directed mainly at the publishers the Literary Gazette, perceived as a lackey of Colburn’s, did not escape its barbs. The issue of 4 September 1830 devoted a whole article to the Literary Gazette, noting that twenty-one columns concerned books published by Colburn and Bentley, but only one-eighth of a column to a book from John Murray’s ‘Family Library’. In fact, the four issues of September 1830 carried over 53 columns devoted to Colburn & Bentley publications, 10 to Longmans, 17 to Murray, 12 to Saunders and Otley and 14 to two other publishers. It is easy to imagine the forceful demands that the aggressive, publicity hungry Colburn made upon his partner, the editor of the Literary Gazette. On one notable occasion however, Jerdan refused to toe the party line, causing the startled Athenæum praisingly to remark that “The Literary Gazette has out-heroded Herod…it has honestly slaughtered Mr Williams (The Life and Correspondence of Sir Thomas Lawrence); but the attack on ‘book-making’ – ‘the tricks of the trade’ – ‘puffing’ and ‘paid paragraphs’ is really so like a column out of the Athenæum, that we imagined we had mistaken the paper, and, feared we had been repeating ourselves” (Quoted Marchand 163).

Unfortunately for Jerdan, who must have felt besieged by the strength and regularity of attacks on his journal, he was linked in business to the odious Colburn and thus laid himself open to the Athenæum’s scorn. The Athenæum of 4 September 1830 had another of Colburn’s journals in its sights too: it noted that in his New Monthly Magazine, a list of forthcoming books comprised ninety-five per cent from the publishing house of Colburn and Bentley, the remaining five per cent being books published by every other publisher in the kingdom. The note concluded ironically “Commend us to the announcements in the New Monthly, but above all, to the criticisms in the Literary Gazette!!!” (566).

Determined to avoid any possibility of the Athenæum being found guilty of ‘puffing’, it was made quite clear that it would accept only advertisements which were indisputably advertisements, and would reject anything smacking of a ‘paid paragraph’. Lest any reader should doubt its intention or confuse its ethos with other literary journals, Dilke announced loudly in January 1831 that: “It surely ought to be enough for one house to have property in, and therefore influence over, the Literary Gazette, the Sunday Times, the Court Journal, the New Monthly Magazine, and the United Service Journal without shaking the public faith in every other journal in the kingdom by criticisms, which, we again repeat, were all paid for.”

In addition to inserting his ‘paid paragraphs’ into as many papers as he could, Colburn also sent free extracts from his books to country papers who were often glad of such material to fill their pages. This was the practice Jerdan had discussed in his ‘Cut-and-Dry’ article, and of course, this practice was also not to the Athenæum’s liking. Neither was Colburn’s habit of sending review copies to his favoured journals pre-publication. As the Athenæum was obviously not on his list at this time, they reacted badly to a letter from the publishers “asking them not to print a review until due notice of publication had been given”. This was a gift to their satiric pen: “this honest testimony to our integrity by Messrs. Colburn and Bentley deserves our best thanks., When did they ever serve a like notice on the Editor of the Literary Gazette? We ask Mr Bentley if he interfered to prevent the review of the first number of the Juvenile Library from appearing in that paper previous to the publication of the work itself?” (540; quoted Marchand 131).

The following issue again complained that the Literary Gazette had prior information, (and indeed, Hood quipped that ‘Jerdan does not review books, he previews them’ [Kitton 47]), and enthusiastically praised a book which the Athenæum and other independent literary papers had been embargoed to discuss until a later publication date. Jerdan did not have it all his own way, however. He wrote to Colburn and Bentley in August 1831 complaining: “The next time you send me an early publication in common with the Athenæum, however little you may care for the Gazette, I will be obliged by its being mentioned in order that I may avoid similarity of appearance, so injurious as today between an 8vo and a 4vo publication.” Colburn’s partly illegible scrawl on this note is something to the effect that “I have frequently pointed out the necessity of a better management so as to give the LG the priority interest …totally to give advantage to Mr Jerdan…” Trying to hedge his bets by supplying more than one journal with an early publication, he succeeded in alienating them all. The problem did not disappear, although the preference turned towards the Athenæum. In 1832 Jerdan wrote to Bentley an uncharacteristically furious letter pointedly marked “not private”, in which he chided:

As I perceive you coquette so entirely with the Athenæum while you pretend to give me a priority, I beg to say that my only objection is to be mystified in this manner. You are as welcome as you can be to be exclusive where you think fit and all I ask is (1) not be told Clouds, and (2) not to be induced to make the LG in its contents the like of any other publication, so that a heedless reader of a puff might not tell the one from the other. If you chuse to whore your favours you will find that virtue would be better than prostitution.

As it is, I do not know how to treat your early favours. One does not like to be laught at for boasting of a preference in such consarns. My rule is, if unpublished I will not blame where I cannot praise – the issue is with you, and I would rather not have common copies upon which I may not justly exercise my discretion.

His fight was always for a degree of independence that Colburn, in particular, was not prepared to permit. The Athenæum was not alone in fighting Colburn and his fellow publishers. According to Marchand, Blackwood’s disliked Colburn not so much for his puffing, but for his vulgarity in “encouraging broken down roués to write memoirs of the society from which they had been cast” (Marchand 153).

A change in literary tastes occurring at this time was marked by the debut in February 1830 of Fraser’s Magazine. Poetry, personified by the Romantics including Landon, had lost much of its popularity, replaced by the ‘silver-fork’ novels, and the era of what has come to be known as classic Victorian fiction had not yet quite begun. The change was not clear-cut. W. St. Clair’s The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period argues that at the end of the ‘romantic period’, the oft-quoted shift from verse to novel was based on evidence from catalogues and advertisements, which does not take into account the fact that a book might have sold only a tiny number of copies. Verse still came from the aristocracy or gentry, often privately printed and attributed by name. Poetry by others, moved down socially and materially, was published in smaller books and needed to be pushed onto the market, whereas purchase of novels became demand-led. The advent of stereotype rather than the slow and tedious moveable hand setting meant that editions did not vary as they had previously, and that popular books never went out of print. Authors and would-be authors were constantly on the look-out for publications to take their work, and Fraser's came along to fulfil their need.

The new monthly publication promoted reality against romanticism, launching what J. H. Buckley in The Victorian Temper “a merciless assault on the lesser disciples of Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron, on the pretentious Edward Bulwer and the ‘satanic’ Robert Montgomery. They flayed alike the rhetorical bombast of Mrs Hemans and the lachrymose nostalgia of Tom Moore” (29). Fraser’s politics were Tory, a sworn rival to Colburn’s Whiggish New Monthly Magazine. The largest part of the new periodical was written by Maginn, recognisable by his biting satiric tone. He was the nominal editor of Fraser's between 1830 and 1836 assisted by Thackeray. Although it was immensely popular, selling about 8700 copies at a cover price of two shillings and sixpence in its first year, its proprietor James Fraser, did not make a profit that year. He paid well, although not so much as Colburn, who reputedly paid twenty guineas per sheet (sixteen pages) for the New Monthly Magazine; the Quarterly paid about sixteen guineas, but Fraser paid according to the value of the contributor, offering Thomas Carlyle fifteen guineas a sheet, rising to twenty pounds, and Thackeray ten pounds, equal to twelve shillings and sixpence per page (Leary). These payments were comparable with those Jerdan offered Griffin (a guinea a page) and Pyne for ‘Wine and Walnuts’ (three pounds for three pages) but possibly less than he paid for Literary Gazette reviews reflecting the decline in the Gazette’s circulation, at this time calculated to be about seven thousand. Maginn earned about six hundred pounds a year for his editing and contributions to Fraser’s, less than Jerdan was making for his comparable work on the Literary Gazette.

Fraser’s flung itself into the ‘puffing’ controversy, the April 1830 issue hitting out at Colburn’s practices, calling him the “Prince Paramount of Puffers and Quacks” (318-20). They included in their opprobrium all his editors, with the single exception of “honest Mr Jerdan”. Jerdan was a member of the twenty-seven strong group of Fraserians, famously drawn by Daniel Maclise carousing around the table in Fraser’s office at Regent Street. Members included Fraser’s editor, William Maginn, Thackeray, Galt, Hogg, Coleridge and other luminaries. However, it has been pointed out that of the twenty-seven men pictured, eight, including Jerdan, wrote nothing or only once for Fraser’s, but were included to enhance the prestige of the publication (Leary).