erdan wrote his usual new year letter to Francis Bennoch, thanking him for the “Carte” with which Marion was “much gratified," and “admires the likeness and expression" (24 January 1863, MsL J55bAc, University of Iowa Libraries). The "Carte de Visite" was a small photograph mounted on a card the size of a normal visiting card, and had been introduced in France in 1854; it was a popular format in Britain throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Not to be outdone, Jerdan reported that he had “sat to Mr Carrick according to orders, but the sun was not favourable and the artist feared there was not force enough to afford the Negatives." The Carrick mentioned was most likely to have been Thomas Heathfield Carrick, miniature painter turned photographer. Between 1841 and 1866 Carrick exhibited his miniatures at the Royal Academy, his sitters including some of Jerdan’s associates and acquaintance, such as Lord John Russell, Eliza Cook, William Macready and William Farren of the Garrick Club. Towards the end of this period Carrick started a photographic studio in Regent’s Circus, London which failed in 1868. Because of Jerdan’s mention of negatives, he was clearly sitting for a photograph rather than a miniature. This photograph has not been found, and the only known photograph of Jerdan was by Charles Watkins, whose studio, with his brother John, was well known for its portraits of “artists and culturally influential people in the years between 1840 and 1875” — this one is in the Rob Dickens Collection at the Watts Gallery, Compton). It shows Jerdan seated, holding a cane in his right hand, and looking squarely into the camera. His hair has thinned, and his raven locks have turned to white or grey, and he sports a drooping moustache. The strong similarity to the earlier sketches and engravings attest to the various artists’ skill in depicting their subject.

erdan wrote his usual new year letter to Francis Bennoch, thanking him for the “Carte” with which Marion was “much gratified," and “admires the likeness and expression" (24 January 1863, MsL J55bAc, University of Iowa Libraries). The "Carte de Visite" was a small photograph mounted on a card the size of a normal visiting card, and had been introduced in France in 1854; it was a popular format in Britain throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Not to be outdone, Jerdan reported that he had “sat to Mr Carrick according to orders, but the sun was not favourable and the artist feared there was not force enough to afford the Negatives." The Carrick mentioned was most likely to have been Thomas Heathfield Carrick, miniature painter turned photographer. Between 1841 and 1866 Carrick exhibited his miniatures at the Royal Academy, his sitters including some of Jerdan’s associates and acquaintance, such as Lord John Russell, Eliza Cook, William Macready and William Farren of the Garrick Club. Towards the end of this period Carrick started a photographic studio in Regent’s Circus, London which failed in 1868. Because of Jerdan’s mention of negatives, he was clearly sitting for a photograph rather than a miniature. This photograph has not been found, and the only known photograph of Jerdan was by Charles Watkins, whose studio, with his brother John, was well known for its portraits of “artists and culturally influential people in the years between 1840 and 1875” — this one is in the Rob Dickens Collection at the Watts Gallery, Compton). It shows Jerdan seated, holding a cane in his right hand, and looking squarely into the camera. His hair has thinned, and his raven locks have turned to white or grey, and he sports a drooping moustache. The strong similarity to the earlier sketches and engravings attest to the various artists’ skill in depicting their subject.

The children of Jerdan’s third family were close, as he told Bennoch: “Willie [William, born 1841], was down for two of our birthdays, (Marion’s with Teddie’s added),” and Jerdan was grateful to Bennoch for undertaking to write a letter of recommendation for William junior, and also to ask him to visit. “We know the value of a little countenance in the struggling time!” He had been to Town, and enjoyed his visit, and was cheered to find several letters on his return home. He had not been entirely forgotten. He felt his health considerably mended, to the point where “If the pressure was not so very – very – heavy, I do believe I might yet show a few flares of light before my sinking taper went out. But when ‘Give us this Day’ and ‘Deliver us from evil’ are the most anxious burthens of the Prayer, it is of small use to think of mental exertion or literary effort.”

Three of Jerdan's "men." Left to right: (a) Isaac d'Israeli (1766-1848), Benjamin Disraeli's father. (b) George Hamilton Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (1784-1860), by John Partridge. c. 1847. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 750. (c) Thomas Cubitt (1788-1855), detail of his statue in Dorking, by William Fawke (1995).

He did, however, make strenuous literary efforts in this period, the Leisure Hour carrying fifteen "Men I Have Known" articles over twelve issues from February to November. These included Perry of the Chronicle, d’Israeli the Elder, Pinnock and Maunder, Dean Buckland, John Trotter and the Rev. T. Frognall Dibdin. The subject of his failed attempt to research him in the British Museum, James Holman the Blind Traveller, was published in June, followed by Robert Southey, the Earl of Aberdeen, Thomas Cubitt and William Bullock of the famous Egyptian Hall. The final contenders in this year were Wordsworth, Sir David Wilkie and Archdeacon Nares.

Jerdan sometimes sent a copy of these occasional pieces to his old friends and frequent hosts, Lord and Lady Willoughby de Eresby at Drummond Castle near Crieff in Scotland. He was happy when Lady Willoughby replied, and now and again sent him a basket of produce from the estate, no doubt well received in his crowded cottage full of ever-hungry children. His gratitude was pathetic, plainly demonstrating his fall from sought-after editor and jolly companion to impoverished and lonely old man. “I assure you in perfect truth”, he told her, “it has become almost a passion – a basket (I have to give thanks for one three weeks ago) – a letter – any sign of my not being forgotten, is a jubilee, of which it is impossible for your Ladyship or my Lord to imagine the enjoyment” (25 September 1863, National Archives of Scotland, GD160/316/34). He sent her the Leisure Hour with his sketch of the late Lord Aberdeen, and mentioned that he had read of Earl and Lady Sefton visiting Drummond Castle recently. This had prompted old memories, and he asked his patient correspondent,

Can your Ladyship recollect a sudden storm on the Lake which drenched the fair Lady, in thin costume, whom I was trying to boat, to the skin. I remember your Ladyship’s amusement when I brought my half-drowned charge home and presented her as Lady Muslin or Muslineux... I trust that this, like other of my exploits at Drummond Castle, may not come to be misrepresented – but Albrecht [Lady Willoughby’s son] told my friend Durham, the sculptor, that I went out shooting in my dress-shoes – which is certainly a libel, to be denied if ever I should meet my young friend of old.

His humour was laboured, and at last he confessed:

I have passed a sad year, amid painful privations, reducing me so low as to render even partial recovery very precarious. As it is, I am now brought face to face with the cold, wintry weather, most unprepared for the struggle and liking to hum Dibdin’s ballad [Charles Dibdin (1740-1814) wrote "Tom Bowling," a song mourning a dead sailor]. Whether to live or die, the Doctor did not know, and it is all I can now do, as patiently as possible await the issue, avert the dark thoughts, and encourage the cheerful... P.S. Oh, I might hope for another letter – angel visits.

In December he wrote to Lady Willoughby again, to thank her husband for his “vital succour,” quoting a French writer: “‘Woe to him who depends wholly on his pen....’ I am afraid that disappointment and woe are only too certain to the man who has sacrificed a life to literature and depended upon the result. Always unapt for business it has made a sad wreck of my closing years, for the comparative blest comfort of which I again and again return my heartfelt acknowledgements” (1 December 1863, National Archives of Scotland, GD160/316/35). Jerdan had not taken to heart the many criticisms of his Autobiography about his constant complaint that literature had caused his poverty when in fact it had been his own profligacy.

He enclosed for her Ladyship some of his “latest trifles in print”, telling her with some disgust that the editor of the Leisure Hour had taken his story, “The Godless Ship,” “and docked it in the Sunday at Home without my cognisance, where I do not like it so well and I like still less a small splice or two of lower-church phraseology, which is not in my style.” The Sunday at Home, sister paper to the Leisure Hour, started two years later, was designed to promote wholesome family reading. Jerdan’s tale appeared in two instalments, on 7 and 14 November 1863. It was based on a true incident about a competent master mariner whose single fault was his ignorance of religion. No services were held aboard his ship, no thanks were given to God for nature’s wonders or deliverance from storms. Jerdan told the story of a voyage to Australia in 1859 when the ship was embroiled in a terrible hurricane, badly damaging the vessel. The skill of the captain and crew repaired it, but neglected to offer prayers for their salvation. The narrative centred upon a death leading to such a brawl that the Captain had the instigator put in irons. Morale on the ship became low, and the vessel was “a hell upon the face of the tranquil waters”. The captain refused to land, as he would then have had to commit his prisoner to gaol, and preferred him to suffer his punishment on the ship. Vengeance and rage was rife, leading inevitably to a climax, when the first instalment ended.

The second instalment took up the tale when “the avalanche of evil was at hand.” Suspicious officers, discontented crew, and wretched, beaten boys ruled over by a tyrannical captain made for a desperate situation. Suddenly, the ship struck an iceberg creating a huge leak which only the strength and skill of the imprisoned sailor could repair. The captain was forced to release him from his chains; he dived into the icy waters and covered the hole with a sail, stemming the inrushing water. Afterwards however, he was responsible for another death. The crew mutinied and the murderer killed the captain. Jerdan vividly described the ensuing mayhem. All officers were murdered and thrown into the sea – no evidence could be left to indict the murderers. “Oh, what a reckoning for those who had never bent a knee in supplication to their God; who had never acknowledged his infinite mercy in a Redeemer...” were not Jerdan’s words, but the Editor’s, determined to reinforce the Christian message of his paper. The ship’s owners, believing after many months that the vessel had been lost at sea, were paid out by the insurers, and were amazed one day, when two boys, the only survivors from its crew appeared in their offices to tell their tale: how they had waited until all the men were insensibly drunk, and killed them, and how the two had somehow brought the ship to shore.

The dreadful fate of all these men was, in the Sunday at Home, put down to the captain running a “Godless ship”; the Christian message was spelled out more clearly than Jerdan would have originally written, an editorial intervention he was unhappy about but powerless to amend, not having been asked for his views or permission to alter his story. The two boys did not escape retribution for their own killing spree. They were awarded salvage money, with which one drank himself to death within three months, and the other embarked on an emigrant ship which never arrived at Sydney. Jerdan told Lady Willoughby that he had heard the tale from “the freighter of the vessel, my neighbour here, Mr Hodgson, Governor of the Bank.” Kirkman Daniel Hodgson (1824-1879) lived across the road from Jerdan, in a mansion called Laurel Lodge, later known as Sparrows Herne Hall, from 1845-1869. He was MP for Bridport and in 1863, Governor of the Bank of England. The Editor had somewhat softened the details of the tale, Jerdan told Lady Willoghby, “to avoid sensation writing, as in truth the crew were killed by the boys literally cleaving the sculls (sic) of their persecutors with hatchets when they were drunk.”

This was a violent story without any morality, transformed by the Editor into a tale where Christian redemption would have saved everyone had they only been believers. Jerdan’s own Christianity was an integral part of his upbringing but not, from his actions, central to his life; he would have been far more interested in the narrative and action of his story than its Christian message. He also sent his correspondent other extracts, these from the Leisure Hour, including “a brief sketch of Wilkie and the account of the painting of the Rent Day for the King of Bavaria.” Jerdan sent a small packet to Drummond Castle before Christmas, “to repair some blundering I discovered in my last enclosure” (5 December 1863, National Archives of Scotland, GD160/316/37). He also sent, marked as “For Lady Willoughby de Eresby”, an old Jacobite song entitled "Culloden" by Nicholson. It began “The heath-cock craw’d o’er muir and dale”, and the last two lines read “The sword has fallen frae aut his hands,/His bonnet blue lies stained and bloody!” Jerdan commented that “The change of chorus in the last verse seems to me most touching and the mere allusion to the sword and bonnet the soul of poetry” (n.d., National Archives of Scotland, GD160/324/38).

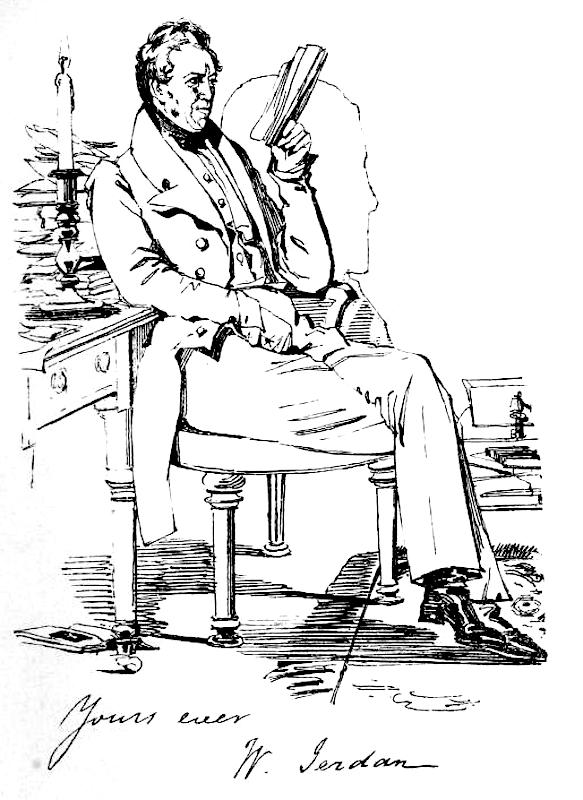

William Jerdan, from William Bates's The Maclise Portrait-Gallery of "Illustrious Literary Characters" (1883). Facing p.1.

He never lost his innate love of literature. Acknowledging that he wanted a favour, he told Bulwer of his novel The Caxtons, “if ever there was a classic in any language will last as such in the English tongue. How great a success in so small a compass!” (6 October 1863, Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies, D/EK C/11/25). The favour was once again on behalf of one of his sons, this time Henry, who was now twenty-six. Jerdan’s sketch of his son’s life to this point is poignant and telling:

As the Great Patron of the Drama I have sent you a Bill in which I am deeply interested. Do you remember helping me to redeem my son from the harsh military servitude. That effort failed and the effort was dissipated; my poor lad remaining, as you may see, from the Bill, playing female characters, which bespeak no athlete form or constitution. He is indeed a gentle boy, affectionate and deserving. Once before he came home the only soul saved from a fine merchantman in which he sailed from Liverpool; and it was upon another visit to that Port in which he failed in his object that he enlisted rather than return to be a burden on his father. Well, you may truly say What is that to me, and I can only reply it is dear to me on the very out-boundary of life, and the help of friendship will be a delightful illumination of the flickering lamp. His companion […] the husband in The Rifle is being bought off, and if Henry can be restored to liberty, has offered to take care of his “Wife” till better can be accomplished. Thus has been my urgency but I am very powerless.

The following year Jerdan reported to Bennoch that "Harry" was a Corporal in Canada, a life that may not have been appropriate for “a gentle boy.” Later in life he did indeed become a professional actor.

In November, Jerdan’s son Walter, now aged twenty, came for his Sunday visit to the family on Bushey Heath. Jerdan gave him some money to deliver to Bennoch, on the way to his office in Gresham House. The money was to repay Bennoch for helping him with the draper’s bill. Jerdan also sent some papers for the archives of the Noviomagians, marvelling how time had flown since his convivial days in their society. Now, he told Bennoch, “I am pottering out and near the end of my journey. It may be that we have a few cheerful meetings yet, but such angel visits cannot be far between” (1 November 1863, MsL J55bAc University of Iowa Libraries). Jerdan’s references to “angel visits” may have been his attempt to avert the evil eye but he had a few more years still left to him and a major book to produce. In December he wrote to an unnamed lady, “It is a well-known fact that I am not a millionaire. Yet, though set down for it, I never was a careless man. I was naturally and simply regardless of money, as I am still, and shall be till cemetery time...” (Leisure Hour, December 1869, p. 813). Jerdan seemed oblivious of the fact that his being “regardless of money” had caused hardships to his family, annoyance and embarrassment to his friends, and the loss of his own hard-won good reputation.

The Leisure Hour, having featured of many of the “Men” Jerdan had known in the previous year, soft-pedalled in 1864 with his series appearing in only three issues. Sir James Ross and the gastronome Dr Kitchiner were featured together in October, with John Britton the following week, while Sir Francis Chantrey the sculptor made an appearance in December.

The year began and ended with letters to Halliwell, the first enquiring for information about Shakspere’s (sic) purchase of the Stratford property, and offering to call on an imminent visit to town. The old tone of friendship had disappeared, the greeting being “My dear Sir,” but in his Christmas letter he was back to “Dear Halliwell.” This letter was used as an excuse to wish his friend happy years ahead, and was ostensibly to draw Halliwell’s attention to his “correcting Clare’s Poems for a friend, and have met with a number of Northamptonshire archaisms...” (19 December 1864, Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections Department, LOA 6/24). He listed several, including “soodling: up and down strolling” and “chumbled: food storing by dormice.” The novelty of such localised words might have charmed Jerdan now, although in earlier years he had criticised Clare’s "The Village Minstrel" for words judged “radically low and insignificant ... too decidely provincial...” (Literary Gazette, 6 October 1821, with thanks to Cynthia Lawford for bringing this to my attention). Always ready for any kind of word-play, especially puns, he explained to Halliwell, “Some time ago I amused myself by putting together a collection of slang and fashionable mis-used words to send to some magazine, and when I saw Mr Hotter’s publication reviewed, I wrote him a note to say I had such matter to which he was welcome, without fee or reward, if he thought it might be of any use to him. He had not the civility to acknowledge my letter. If you have any intercourse with him, you may say that I tell the anecdote not to his credit.” Jerdan had conveniently forgotten the times when he himself had delayed responding to similar letters. He was thirsty for any news, asking Halliwell for advice on the best Shakespeare editions, and whether Halliwell had made any new discoveries. “Aught to relieve my monotonous life (after all my busy one) will always be prized....” A while later he was still thinking of Clare’s Northamptonshire poems, illustrating his love of unusual words: attempting a synonym for “dandering” he told Halliwell, was “Wandering helplessly, does not quite express it”; for “hirpling,” “Crippling is not feeble enough” and so on (Letter to Halliwell, 8 February 1866, Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections Department, LOA 105/19). He had recently been to London and dined with Vice Chancellor Stuart and slept in Brompton, but had not managed to call on Mrs Halliwell; his letter was “merely a passing thought to show that I am still alive and mindful of old friends.”

He was not entirely forgotten, as a booklet published in March by the London Society called London Papers and London Editors devoted more than four of its sixteen pages to him. It referred to his Autobiography, written to “coin his own life into money” after literary interest in him failed. The writer called the volumes “Queer, rambling, gossiping, egotistical books the most of them are, in which a good story, or a curious bit of local history, or some half-forgotten incident of parliamentary warfare is found overlaid with heaps of rubbish ... the reader [must] surrender himself to the illusion that of all the men there described, Jerdan was the foremost – of all the scenes he was the hero.” The rest of the article paraphrased the Autobiography and featured the quasi-sonnets on Byron which Taylor and Jerdan had printed in the Sun, forty-seven years earlier.

Jerdan’s main focus now was on his family, and in response to an enquiry from Bennoch as to their welfare, he set out what his “boys” were now doing. The “boys” he referred to were his sons with Mary Maxwell, the children of his first two families being now either deceased or grown up, some with families of their own. This letter to Bennoch, of 15 March 1864 (MsL J55bAc, University of Iowa Libraries) reveals more details about his family than any other single document yet discovered, and one can feel Jerdan’s relief that some of his brood were making their own way in the world:

You ask about the “Boys.”

1. Charles, a first Engineer, Galatea. Has just earned high praise by his gallantry in descending six or eight times in Diving dress to ascertain the injury the fine vessel had received in a hurricane. I am told the service is likely to promote him [Charles Jerdan of the Galatea was, in fact, promoted to First Class Assistant Engineer (The Scotsman, 29 August 1864], as the repairs of the ship abroad or at home rests on this examination of the very machinery he helped to make at Penns!

2. Harry, your old vis-à-vis in Canada – a Corporal!

3. Wm at Penns. Has been home a fortnight covered like Lazarus with boils. Is better and hopes to go with his regiment to the Review on Monday.

4. Walter in the Telegraph office Gresham House – under £40 pr ann. He and Wm mess together at Greenwich.

5. Gilbert at home – poor gardener nothing to do etc. Ahoy

6. George (Tiny) has been a fortnight with Mr Bickley a stock and insurance broker Union Court, Wood Street. He is brother of C. Bickley Matilda’s husband – a character – but seems willing to give Tiny an introductory training at nominal wages.

The younger boys are thriving on the Heath and short Commons – the youngest a vast pet, and very interesting in countenance and manners.

As for me, I am off and on. Now and then expecting the Crisis; then rallying, and holding on through coughs, colds and the long etceteras that pertain to fourscore. When I am in good case I really thrive wonderfully and it is only at straining epochs (too frequent) that I bid so fair to fall off my perch.

Oh if I had the power to show you how I value yr friendship by lending you a lift, you would not be able to fancy me a mere Begging Letter Importer. I am sick of myself, yet always the same.

The “Penn’s” mentioned as ex-employers of Charles and where William was currently employed, made ships’ machinery; the boils suffered by William, and at an earlier time by Charles, could well have been caused by the lead used in such a manufacturing process. “Harry” was the Henry who, in his youth, had so admired Bennoch, and who was following in the family Army tradition in the footsteps of his uncle and older half-brother, having recently tried his luck upon the stage.

Jerdan’s final group of "Men" for his series in the Leisure Hour featured Lord de Tabley, founder of the first Gallery for British art, coupled in February with the famous artist Sir Thomas Lawrence, followed by another artist Sir David Roberts, in June. August was given to Jerdan’s dear friend Sir Willoughby de Eresby, September to Forbes and the final contribution in this series in October was devoted to John Galt.

From the depths of his isolation and despair, his fear of being forgotten and abandoned in the previous two or three years, Jerdan seemed to have taken on a new lease of life in the summer of 1865. He accepted an invitation from Halliwell delivered by Wright – his two collaborators on the Camden and Percy Societies – to attend a dinner in town. His good mood continued although he had been ill again, telling Halliwell on 23 September,

Dic mitic who was the author of Chrononhotonthologus – about what period etc. I hope you are all well with Mrs Halliwell and daughter enjoying the country or returned like Chinese gigantics refreshed, to partake of the comforts of home. I have just weathered an attack of gout on the head, which is a very grave matter; but I may yet live to see you with a better vis-à-vis at table than, Dear Halliwell, Yours very sincerely, [Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections Department, LOA 107/47.

His better mood was because he had been hard at work again on his final book, Men I Have Known, based on his Leisure Hour articles.

Jerdan was very unwell. He suffered from chronic bronchitis, as he wrote to Bulwer on 14 March 1863, “provoking cough and phlegm with considerable effort and exhaustion” (Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies, D/EK C/11/24). His hand-writing was unusually shaky, when he asked Halliwell in December, to vote for a Mr Acworth at a meeting of the Society of Antiquaries (Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections Department, LOA 104/13). Having left the Society many years earlier, he had no direct influence, but would have been happy to think that his opinion could still make a difference.

He still managed to keep in touch with his daughters by Landon. A surviving letter to Ella in Australia reads:

My dear Ella, I send you my Autograph at the age of Eighty-four and upwards – rather downwards. I think you have neglected me a good deal, but I rejoice, not the less, that you are well-doing in the world. Laura is a dear Creature and I love her beyond expression. I have been greatly pleased with the accounts of your children. Perhaps the new generation in the next few years may lead to many acceptable recognitions when I am in the grave. Till I go, believe me Ella to be most affectionately Your, W Jerdan. [Lawford, Diary]

Jerdan’s letter to Ella did not use the terms "daughter" or "father" perhaps from a sense of concern that such acknowledgement could somehow compromise him, his latest young family or Ella herself. His rather wistful hope that his paternity might eventually be recognised is a touching insight into the heart of a loving and gentle man whose faults were many, but never included neglect of any of his children. Jerdan took a great interest in them all, using whatever influence he had to assist them in gaining positions or advancement. Unfortunately, nothing has been found to support this interest in the case of Fred Stuart in Trinidad, but the absence of surviving evidence does not mean that it never existed. Laura Landon had been well placed with the Goodwins and needed no support from Jerdan, and Ella Stuart had married well and was secure. Ella and her half-brother Charles met in Melbourne during the visit of the Galatea on which "Coz Charlie" was an engineering officer. It was a ceremonial trip captained by HRH The Duke of Edinburgh (Milner, The Cruise of the Galatea). There were several weeks between November 1867 and January 1868 whilst the ship was in Melbourne when the officers had considerable free time, and it was likely to have been during this period that the two children of the same father but different mothers forged a friendship which continued to future generations.

Suddenly, Jerdan was busy again. He told Gaspey, “I am plunged in press-correcting and know not of the hour to spare; and, my friend, I am not so alert as I was with brain, pen and limbs. I cannot walk far.... I am seeing my volume of Eminent and Exemplary Men I Have Known through the press – and the task has been and is quite and more than quite enough for my old head. I expect little from the publication but hope it will be some small help” (24 January 1866, Huntington Library, San Marino, California). His activity was a welcome distraction, as he had other news to tell his old friend: “My two boys sailed for Adelaide on Tuesday and I have just had a good (female) cry over their Farewell letters from Plymouth.” The boys were George, known as "Tiny," and Gilbert, who arrived on 16 April 1866 on the Atalanta. Their voyage of eighty-one days had been plagued by severe winds and then long calms; seven children died on the journey (Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild, "Arrival of the Atalanta with 394 Government Immigrants"). Worse than two sons going off to make their lives in Australia was the untimely death of his daughter Tilly at the age of 29. She left two daughters for her husband Charles Bickley to care for. He remarried at the beginning of September 1868, a Julia Archer, and died in 1877 aged 38.

Jerdan compiled his book from the Leisure Hour articles with no certainty of getting it published. He originally offered it to Richard Bentley, whom he had yet again somehow offended greatly, without knowing why.

I was sorry to hear from Mr Macaulay that you did not think my Volume had sufficient interest for the risk of publication. Your letter, declining it, has somewhat touchingly recalled my memory to other times, when, for many years, you and I held on together in very friendly and pleasant intercourse and I passed many happy social days in the enjoyment of your personal intercourse, not uncongenial with our little literary concerns.

I am aged now, and regret the more that any misunderstanding should have broken off this agreeable state of relation, but I never felt otherwise toward you but to wish you well with all my heart, and so it was not in my power to mend the rent. [6 November 1865, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin]

Title page of Men I Have Known (1888 ed.).

In April, Men I Have Known was published by George Routledge and Sons. The genre of biographical sketches mixed with memoirs was popular at the time and, with the vast acquaintance he had accumulated over the years, coupled with his experience of biography writing for Fisher’s National Portrait Gallery, Jerdan was well placed to make his own contribution in a huge effort to swell his coffers. Routledge printed one thousand copies. Their costs of composition, engraving, machining and paper totalled just over £189. Jerdan’s royalties were a few pence over £48 (Routledge Archives, Publication Book, Special Collections Library, University College London). Considering that much of the material had already been paid for by the Leisure Hour, this was a sum he would have been satisfied to receive. The book was a collection of all his pieces for the Leisure Hour, and Jerdan dedicated it to his “Dear Friend”, Rt. Hon. The Lord Chief Baron Pollock, referring him to the entries on Truro and Hallam especially, as they mentioned Pollock. Emotionally, Jerdan’s dedicatory letter continued, “But, above all, an intimate friendship rendered (to my feelings) almost sacred by the extent of its period from youth to age, inspires my earnest wish to dedicate the last of my literary efforts to One who has cheered my path and comforted my toil, throughout every concomitant vicissitude and anxiety. It is but a faint expression of the faithful attachment and affectionate regard....”

The subjects Jerdan chose had all, to some extent, been friends or acquaintances, and he had selected them from amongst writers, poets, artists, scientists, politicians and explorers; very few had appeared in his biographies in Fisher’s National Portrait Gallery in the 1830s, but where there were duplications, Jerdan’s treatment of them was completely different. His entry on Wilkie is an example, as in the Portrait Gallery Wilkie’s status and artistic achievements were paramount, but in

Jerdan’s style throughout was, as the title indicated, that of personal experience of the history and character of his diverse subjects, positive and uncritical, but not sycophantic. His articles and Addenda formed a substantial octavo book of four hundred and ninety pages, and included a Postscript in which he vouched for the truthfulness of his sketches and begged “indulgence for its imperfections”. He had looked back at a panorama of a long life and remarkable personages and others who had been forgotten. “For the rest,” he continued, “it is a weary journey to look back upon; and at an age beyond fourscore, with flagging brain and wavering hand be reminded that my work must be very nearly done.” Endeavouring to pre-empt criticism of some anecdotes thought to be “too trivial to contribute effectually to the elucidation of character”, Jerdan invoked the dictum of Horace Walpole who observed that trifles may appear in a stronger light in retrospect. He apologised in advance that only the memory and experience of age can “reveal, verify and satisfactorily discuss”, and that “there are many interesting things which must suffer when left to report and conjecture to determine.” He pleaded unashamedly to any potential critic:

I am still so beset with saucy doubts and fears about my own production, that I would fain bespeak the gentle handling which my shortcomings need…My revelations ought to have been of a higher order; but there are things that cannot be told, and I can only offer my contribution, in its unassuming form, to the fund of general information. May it be accepted!

Such insecurity was sad in a man who, for over thirty years, had been an arbiter of literary taste; here was Jerdan at eighty-four, running scared of adverse criticism such as he had suffered with his Autobiography. It is remarkable that he had managed to produce such a substantial quantity of work over the previous few years, and then added extra material to bolster his book.

Whilst awaiting the reviews Jerdan remarked on his efforts to a friend, “I hope it may be liked. I deserve some praise as revealing some curious facts and exhibiting not a few characteristic traits of my time and Men though in the poor cloudy amber of querulous age” (Letter to Pigott, 1 May 1866, Huntington Library, San Marino, California). He had not too long to wait. On 2 June the Athenaeum noticed his book, only mildly sarcastically:

For many reasons, including the recollection of past controversies (hard enough in their time), this book by Mr Jerdan can be here spoken of only in a tolerant, rather than critical spirit. It is a republication of scattered papers contributed to the Leisure Hour, with annotations and corrections. If literary historians to come fail to find in it those marking anecdotes which are welcome as "illustrating character," they may recognize the placid and gentle spirit befitting one who (as we are here told) in its pages, closes accounts with a long and busy life. There is no reckoning with faults of taste and judgment under the circumstances.

In stark contrast the July issue of the London Review, under the heading "Contemporary Celebrities," moaned:

How wearisome is that class of literature, if indeed it be literature at all, which thrives and flourishes on the rank soil of scandalous gossip, and is popular just in proportion as it gratifies an idle, if not an impertinent, curiosity! "Men Whom I Have Known" – "Men whom I Have Seen" – "Places I Have Visited" – how well we know the contents before reading a page of the volume! Next we shall have "Wives I Have Flirted With" – "Cabmen who have cheated me" – and "Women who object to smoking." These, indeed would be an agreeable change after the inanities under which we have suffered so long. Would that somebody would give us an account of "Men he has not seen," or of "Places he has not visited."

Having complained thus bitterly, the reviewer grudgingly observed, “By these remarks we would not imply that Mr Jerdan’s book is among the worst of its class: there are many things in it which deserve recording, and, were it not so, we could willingly overlook its failings out of respect to the writer’s great and lengthened services to literature.” A few of Jerdan’s factual errors were pointed out, followed by descriptions of his articles on several of his "Men." The review concluded fairly positively that although it could not name all of the "Men," they “refer readers to the volume, where they will find Mr Jerdan’s pen-and-ink sketches lively enough, if not always very new.”

The New Sporting Magazine was much more enthusiastic and right on Jerdan’s wavelength: “Mr Jerdan’s style is delightful to every reader and there is no book in our literature on which we would so readily stake the fame of the old unpolluted English language – no book which shows so well how rich that language is in its own proper wealth and how little it has been improved by all that it has borrowed” (July 1866). Notes & Queries gave the book a warm review posssibly prompted by the prospect of advertisements for it such as duly appeared on 23 June, promising that it “will be read by the public with the greatest pleasure and the greatest profit.”

Just as Jerdan had created Men I Have Known from his Leisure Hour articles, now he attempted to create a further commission from his book. In September he wrote to John Blackwood, son of his old Edinburgh friend William, mentioning his book and in particular the article on John Galt. Galt’s son was now Finance Minister of Canada, and “when he was over in England he and I had some intercommunion about his Father’s life and works,” he wrote (5 September 1866, National Library of Scotland, 4201/15-16). Blackwood owned the copyright and Jerdan asked him whether he thought “there is any fair prospect for a good biography and a new edition of the best of Galt’s works?” Playing on his old associations Jerdan took the opportunity of enclosing a contribution asking for “a place in Maga or if not, that it be sent to his nephew at the Kelso Mail. Not receiving a reply Jerdan approached Blackwood’s London colleague, a Mr Langford, asking if his letter had been delivered. “I am sure no pooh-poohing can be meant. To repel a friendly correspondence which existed 49 years ago when Mr Blackwood and Maga and William Jerdan and the Literary Gazette started together. He never published a Work respecting which I was not immediately informed and frankly interested – not only, indeed, as an influential kinsman but a personal and family friend” (18 September 1866, National Library of Scotland, 42201/17-18). His appeal did not go unanswered, and Jerdan responded gratefully, explaining to Blackwood that he had been “retired and quiet” for more than ten years, and understood that others were “immersed in the engrossing business of life”. His idea for the Galt biography had emanated from his book, he said, but “I fear it must remain an idea”. Regarding the contribution he had enclosed with his earlier letter, he was “half-ashamed to say it was a rhyming attempt to depict ‘The Working Man’ as the coming dictatorial power of the Country and which, if accepted, might have procured me the pride of once more appearing on the page of Maga. Most likely you think that there can be no Jeu d’esprit in a brain over four score years, ramshackling, and I am, myself, pretty much of that opinion.” Blackwood would be fifty in April, Jerdan noted, the same month in which he would be eighty-five.

Jerdan’s brain was not “ramshackling” at all, but reinvigorated by his renewed activity. He took up his interest in the magazine Notes & Queries and in the second half of 1866 there appeared thirteen entries under his pen name, "Bushey Heath." These covered topics as diverse as a Relic of Charles I which he had seen as a young man, some explanations of Scottish and common sayings, and a note on the witty sayings of Lord Erskine. His fourth entry was about Blackwoods, a detailed enquiry about a preface found in one early edition but not another. This is signed "T.B." and does not read like a letter from Jerdan, but it is indexed under the name "Bushey Heath." Jerdan’s fascination with words is evident in several of his contributions, as is his humour. As an example, in August he offered, “Is not smittle equivalent to, or a mere variation of smitten i.e. smitten by a disease which if contagious, becomes a smittle complaint?” He discussed the meaning of the farewell blessing “God speed”, and “salamagundy”, “a north country saladian concoction of which a salt herring (instead of the southern lobster) is the primary ingredient. It was a favourite dish years ago, and very relishing and toothsome.” One can hear his lips smacking over his ill-fitting false teeth at the memory! The variety of Jerdan’s Notes & Queries is astonishing; in the same issue he offered a schoolboy version of an old song and a disquisition on the pronounciation and etymology of the surname of the poet Cowper. In December he railed against the careless idiomatic use of English, noting that even in respectable publications one finds "neither" followed by "or" rather than "nor," and other misuses. If he had no other occupation at this time one could understand these detailed and varied contributions, but he was busier than he had been for a long time, so it is evident that such miscellaneous matters were of importance to him, and that he was keen to have his opinion known in the world; but then, if so, why use a pen name?

Lord Lytton, an engraving by E. Stodart from a photographer by Alex. Bassano, in The Life and Times of Gladstone, vol. III.

In July 1866 Jerdan’s long-time friend the novelist and politician Edward Bulwer, was elevated to the peerage, becoming Lord Lytton Bulwer-Lytton. Writing to congratulate him, Jerdan said:

My dear Bulwer, I will once, before I write ‘my Lord’, address you by the old familiar name, to say that in all that can contribute to your honour and happiness I continue to feel the deepest interest. When you were in your youth and I was about my prime, our intimacy began, and in all that has happened to you since – every step by step – it has been my joy and pride, and I may add my acceptable privilege, to go along with you, if possible with good offices and always with good wishes. No living soul can more sincerely congratulate you on your wholly earned elevation to be an English baron. Soft and long auspiciously worn may the coronet be. [July 8 1866, Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies, D/EK C/10/106.]

Their ways, once so intertwined, had gone in such very different directions, especially since Landon’s marriage and untimely death, but it was Jerdan’s instinct to be generous and not envious of his friend’s ennoblement and success.

Jerdan was extremely sensitive about being forgotten in his old age. He had spent many decades in the centre of activities both cultural and political and it was not surprising that his resentment occasionally boiled over, albeit thinly disguised. Evidence for this is a letter he wrote to Halliwell in 1867, having watched his erstwhile close friend and colleague being extremely busy in the preceding period. In 1865 Halliwell was involved in thirteen publications, all of a scholarly nature, in which he edited documents related to his Shakespearian studies. In 1866 a further three appeared, and the catalyst for Jerdan’s letter was yet another volume edited by Halliwell which had just been published in 1867, “Selected Extracts from the ancient registry of the causes tried in the Court of Record at Stratford-upon-Avon in the time of Shakespeare; including many entries respecting the poet’s family.” Most of these and subsequent publications were printed in only ten copies, a fact Jerdan chose to ignore. His April letter to Halliwell read, in part,

Is it not a strange thing that as soon as one is out of the way, people forget their old friends and publish, and publish, and publish, without ever thinking that it might gratify the aforesaid to be complimented with a remembrance. Now, you see I am particularly sensitive on this subject.... I seem to feel, as it were, rather neglected. There is a wise old Scottish proverb, “No more pipe, no more dance” and indeed I can suggest no earthly reason…why there should be any dancing to keep up the ball, after the music has ceased.... I have been confined to bed and chair since March 20th with a severe and dangerous illness, but am again slowly and wonderfully recovering.... [28 April 1867, Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections, LOA 82/12.]

His purpose was to make Halliwell feel guilty about neglecting to send him his publications, but for Halliwell, as with so many other of Jerdan’s one-time friends, it seems to have been a case of out-of-sight, out-of mind.

Jerdan took a break from his entries in Notes & Queries during 1867, with a single exception in February where he commented on historical books dealing with George III. He reported that he had heard, from an informant of “eminent qualifications,” that the King had been able to deal with his correspondence speedily and effectively, demonstrating a clear understanding of the Constitution, contrary to reports in the books under review. Jerdan’s loyalty to the late King is touching if, in the light of better informed history, misguided. He signed his name to a column of “Varieties” in the Leisure Hour of 1 March 1867, which included topics as diverse as nightingales, the American book trade and discharged prisoners.

Bibliography

[Illustration source] Bates, William. The Maclise Portrait-Gallery of "Illustrious Literary Characters. Chatto & Windus, 1883. Internet Archive. From a copy in the Centre for Nineteenth-Century French Studies, University of Toronto. Web. 27 June 2020.

Fisher, J. L., "'In the Present Famine of Anything Substantial': Fraser's 'Portraits' and the Construction of Literary Celebrity; or, 'Personality, Personality Is the Appetite of the Age.'" Victorian Periodicals Review. Vol. 39 (2): 97-135. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Jerdan, William. Autobiography. 4 vols. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co., 1852-53.

Jerdan, William. Men I Have Known. London: Routledge & Co., 1866.

Created 23 June 2020