This is a later version of "A Cut Above — George Meredith and the Landlady's Daughter," published as a commentary in the Times Literary Supplement of 4 September 2015, pp. 13-15. Illustrations, captions and links have been added to the original review. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.

Meredith as a young man, in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's portrait of him in about 1860 (Ellis, facing p. 110).

George Meredith was notoriously reticent about his origins. "Horribly will I haunt the man who writes [a] memoir of me," he wrote to a friend of later years, Edward Clodd (qtd. in Clodd 140). The embarrassment of being the son of a naval outfitter in Portsmouth had dogged him all his life. Like so much else, it found its way into his fiction — his novel of 1861, Evan Harrington, was subtitled in its earlier serial form, "He would be a gentleman," and traces the struggles of a tailor's son who falls in love with a diplomat's niece. But in 1849 when he married Mary Ellen Nicolls, the widowed daughter of the satirist Thomas Love Peacock, Meredith was still only twenty-one, and not prepared to divulge it in any shape or form. On the marriage certificate his father's occupation was given simply but misleadingly as "Esquire." There would be more to obscure later on too, specifically, the events surrounding the breakdown of this first marriage, which inspired his best-known poem "Modern Love." Inevitably, these have intrigued his biographers ever since. Nicholas Joukovsky alone has written three Times Literary Supplement commentaries on or touching on them ("According to Mrs Bennett: A Document sheds a new and kinder light on George Meredith's first wife"; "Mary Ellen's First Affair: New light on the biographical background of "Modern Love"; and, with Jim Powell, "A Peacock in the Attic: Insights and secrets from newly discovered letters by George Meredith").

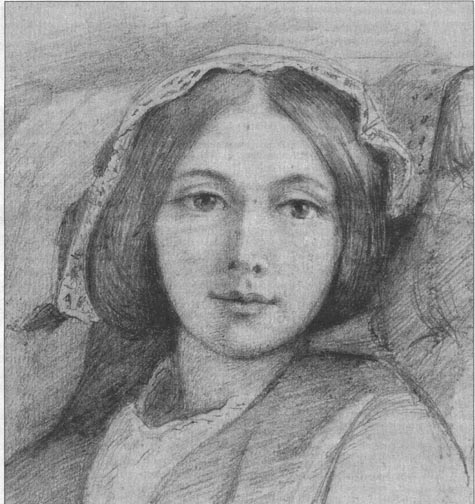

Left: Meredith as Chatterton in Wallis's well-known oil-painting of 1856. Right: Mary Ellen, in Wallis's pencil drawing of 1858.

Yet one contemporary view of the marriage remains unexplored. It is well known that Meredith modelled the tragic young poet Chatterton for the artist Henry Wallis, and that Mary Ellen ran off to Wales with Wallis in 1857. But Meredith unwittingly sat for his portrait long before this. The previous portrait was a verbal one, drawn by Emilie Maceroni, the daughter of the Merediths' landlady when they were first married. Apart from the inherent interest of catching a new glimpse of the situation at its earliest stages, the earlier portrait is significant in two ways. First, it confirms that the marriage was in trouble almost from the start, and that the affair with Wallis was not the cause of its collapse, only the last straw. Secondly, it introduces the author of the portrait. This is useful. Unlike other important figures who featured in Meredith's life, Emilie does not get much of a mention in Meredith studies. For example, not having (as far as we know) been one of his correspondents, she does not merit a biography among the others in his circle at the end of C. L. Cline's exemplary and comprehensive edition of Meredith's Collected Letters. But her family inspired one of Meredith's deepest political sympathies, and she herself inspired at least one, if not more, of his powerful and charismatic heroines.

The Limes, Weybridge, Surrey (Ellis, following p.60).

In 1849 Meredith was stepping into a new world. On coming of age he had received what was left of his maternal aunt's estate, and local historian J. S. L. Pulford tells us that he also came into the then quite princely sum of £1000, which had been settled on him under the terms of his parents' marriage (5). The couple got off to a good start with a wedding at St George’s, Hanover Square, and a honeymoon in the Rhineland, where Meredith was able to show his bride the scenery that he had loved since attending the Moravian Brothers' school in Neuwied. Soon after their return, they took rather special lodgings. The Limes was a grand establishment just over the river from Shepperton, close to Peacock's home in Lower Halliford (now actually a part of Shepperton). It was run by Elizabeth Maceroni, the cultured English widow of "Count Maceroni," a dashing Italian colonel who had been ADC to the King of Naples. She had "two very beautiful daughters, who were, of course, half Italian" (Ellis 61), Emilie herself and her younger sister Giulia. So it was an appealing and lively household for the young couple to join.

The guests at The Limes were a cut above average as well. Aristocratic novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and the narrative and portrait painter William Frith, were among those said to have lodged there (see Ellis 61; William Meredith in Selected Letters 5). Perhaps Katherine Frank is a little off the mark when she suggests that such lodgers made up a "a pale, spiritual band" (160). They seem to have been more spirited than spiritual. Meredith himself was personable, engaging, brimming with life both physically and mentally, and possessed of a great talent for friendship. Unsurprisingly, then, The Limes proved to be an important launching-pad for his career. One fellow-boarder who became both a useful contact and lifelong friend was Tom Taylor, a future editor of Punch, whom he met in 1850 (see Joukovsky "'Dearest Susie Pye,'" p. 616, n.95). Through him Meredith met the titled Duff Gordons, then spending their summers at nearby Nutfield Cottage with Lady Duff Gordon’s parents, the Austins. After a dislocated childhood, and despite having (quite literally) no family to speak of, Meredith seemed to be entering the establishment at last.

Meredith's initial happiness is reflected in Poems of 1851, his first independent publication. One particular poem, "Love in the Valley," caught the public eye; to the fledgling poet’s delight, Tennyson himself admired it. It was a propitious debut, and some readers, like William Sharp (a.k.a. the writer Fiona MacLeod), have wished "that, in his later poetry, Meredith had oftener sounded the simple and beautiful pastoral note which gave so lovely a beauty to his first volume of verse" (57-58).

But this was not the golden period it seemed, or only briefly and precariously so. The Merediths could not afford to go on living in style. Having abandoned any pretence of training for the law in London, Meredith was making next to nothing by the pen. Moreover, his past was not so easily buried. The very year he and Mary Ellen got married, his father emigrated to South Africa, where he settled with his second wife, and opened a tailor’s shop in the Cape. Not long afterwards, as Joukovsky revealed in his 2004 commentary, Mary Ellen discovered a bill he sent his son, for forwarding to a customer (see Joukovsky, "According to Mrs Bennett," 15). At last the truth came out: "Gentleman Georgy" (the telling nickname Meredith acquired at his first school in England) was, in the words of young Evan Harrington, nothing better than "the thon of a thnip" (Evan Harrington, 541). She felt deceived. It is a fair assumption that this was at least one of the reasons why, by the time of the 1851 census, Meredith and his step-daughter, Mary Ellen's little girl Edith from her first marriage, were staying in more ordinary accommodation behind the High Street, while Mary Ellen was in Lower Halliford again with her father.

The unhappy lover, illustrated by E. H. Wehnert in Emilie's Magic Words (following p.10).

What has yet to be realised is how the couple's problems were echoed in a typical girls' "conduct" book of the time, written by Emilie, the elder of Mrs Maceroni’s two talented daughters. She was just of an age with Meredith, and her life too was already moving in a new direction: she had had a punting accident on the Thames one weekend in 1850, and been rescued by a young lawyer called Edmund Grimani Hornby, who was staying in Weybridge at that time, and who also had Italian blood. They were married within the same year, and took a cottage near her family for £20 per annum (Hornby 35). In the meantime, however, while still using her maiden name, Emilie published Magic Words: A Tale for Christmas Time with the firm of Cundall & Addey. Dedicated to Mrs Austin, it is all about the mending of broken relationships by "magic words" of conciliation. It was well received in the Athenaeum of 28 December 1850 as a "poetical illustration of the goodness of a word spoken in season — and yet more, a special application of the Christmas motto, 'Peace and good will'" ("Our Library Table," 1377). Certain particulars in its contents suggest that Magic Words was at least partly written with Meredith and Mary Ellen in mind, and even with a view to healing a rift that had already, at such an early stage, developed between them.

One of the intertwined narratives, and the one with which the books opens, concerns a couple driven apart by dissension perpetuated by pride. It is painfully easy to see behind it Emilie's experience of her mother's boarder and his difficult relationship with his wife. The young man, whose name is Percy, is a writer who loves the countryside and who has taken rural lodgings. He has at this time "a sad and thoughtful cast of countenance, yet one that all who looked upon it must instantly love and respect; it was at once so engaging and so noble" (6). The problem is that, exactly like the eager and persistent young Meredith, Percy had wooed the woman he loved "with all the ardour of his nature and the energy of hope" (8) — only for their relationship to come to grief. No details are given of the rift, but the woman, whom Emilie calls Edith (Mary Ellen's daughter's name, and the name she herself would give to her own first child) lives nearby on a "fine estate" inherited from an uncle (44). Like Mary Ellen, therefore, Edith is the man's social superior. Edith blames herself for what has happened, accepting that she is "a wilful, imperious woman" whom Percy "once foolishly loved" (41), and recognising that she has been responsible for their separation. She knows that she has brought her present misery upon herself.

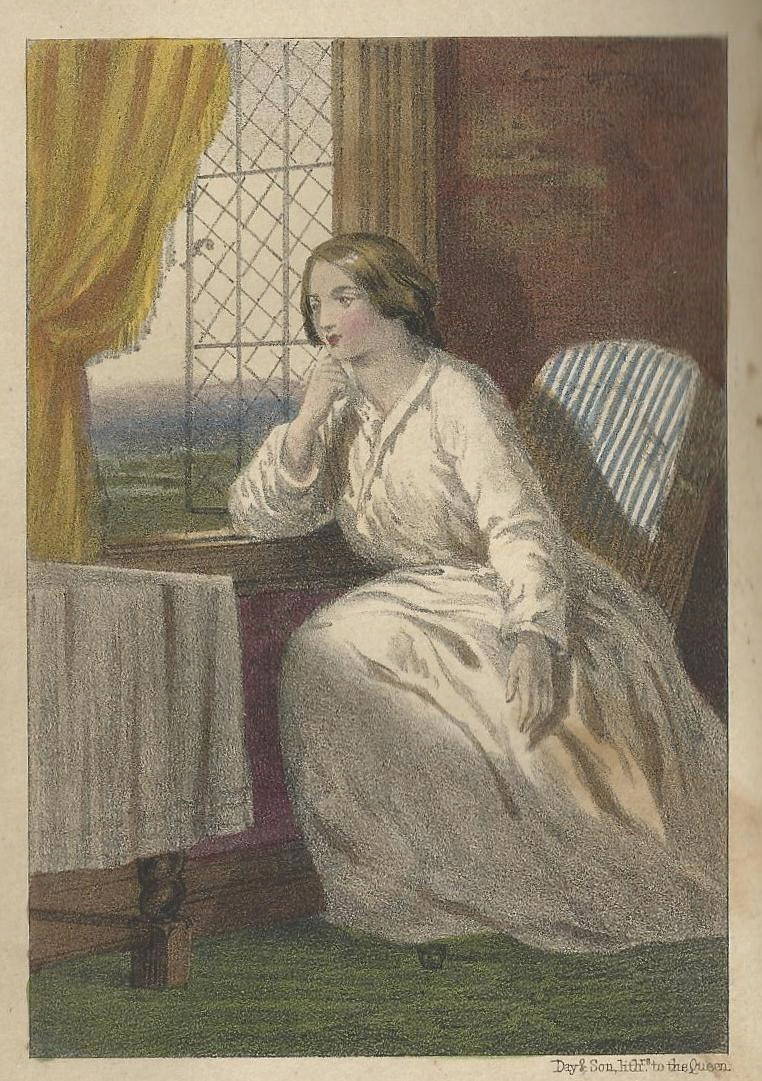

E. H. Wehnert's illustration of Edith in Emilie's Magic Words, entitled there, "Edith watching the Dawn" (following p. 38).

A full-page illustration of Edith by Edward Henry Wehnert, who was very much a part of the artistic circle of that time, bears a strong resemblance to the Mary Ellen of Wallis's portrait. Mrs Bennett (as reported in Joukovsky's earliest commentary) noted that Mary Ellen's "physical appearance" was striking. She was not of a common type (13). Yet the hairstyle and features, the shape of her face and the very soulfulness of her eyes, are identical in both. It is hard to believe that Wehnert himself had not met Mary Ellen and did not have her in mind as his model here.

Missing Percy as much as he misses her, Edith is overcome with remorse: "I shall never see you again — mine the sorrow, mine the fault!" (41). Meanwhile, we are told, Percy has struggled to overcome his hurt feelings by throwing himself into his writing — exactly as Meredith was doing at this stage. Indeed, he has begun to make a name for himself But Percy, again like Meredith, seems to have no other family. He cannot help desponding amid the general rejoicings at Christmas. Just when "his head lay buried in his hands, his whole soul given up to an overwhelming agony of regret" (10), he is visited by Mary, a young girl from the village whom he had once tutored, and has taught to love books. "Why don't you go to her?" asks his protégé (15), knowing full well what his problem is. "Did you speak gently, and ask her to love you again: or were you proud?" (16) The shot finds its target, pride is jettisoned, and Percy makes a start by visiting Edith's friend Marion to get news of her.

Marion's father-in-law has disapproved of his son's marriage to her; theirs is the other reconciliation narrative in Magic Words. Empathising with both the parties involved, Marion urges Percy to attend a New Year's Eve gathering that Edith has arranged at her home. He does so. Unaware of his presence, Edith makes a speech there about the subject closest to her heart, the lesson she too has now learnt, from her own experience:

"There may be some among us," she says, "estranged from friends and kindred, grieving over the fault, (for few, let us hope, in a Christian land, can live unmoved in enmity one with another, and yet hanging back, in mistaken pride or want of moral courage, from the few conciliatory words which would, in most cases, suffice for a perfect reconciliation. The old year is now passing away, — may it bear with it all anger, all animosity! May those few healing words be spoken, — and Peace, and Love, and Charity be with us all!" [51-52]

At this, Percy, who has hidden himself in a recess at the back of the gathering, is moved to come forward. Edith sees him and hurries to him: "And Percy and Edith once more stood side by side, — united, happy!" (53).

Here was a suitable message for the older girls, and future wives, whom Emilie was addressing, perhaps also for a certain young couple in her Weybridge circle. If so, it indicates a marriage that was in trouble almost from the start. Meredith and Mary Ellen were also reconciled, at least for a while. The marriage limped on for several years, producing one son, Arthur, who was born at Peacock's house in 1853. The couple had been staying there since about November 1851 (see Joukovsky, "Dearest Susie Pye," 602). Soon after the birth, Peacock took a house for the young family just across the green from him, the rather cramped Vine Cottage on Russell Road. Perhaps this is an indication that there had been too much disruption to the older author's routines, if not actual friction to disturb his peace. For the marriage was now under more financial strain than ever: Meredith told Clodd later that there were literally "duns at the door" when he was writing his first piece of fiction, the exotic Eastern tale of The Shaving of Shagpat (Clodd 141). At this time too we find Mary Ellen thinking up a scheme to augment the family income by running a servant-girls' school. It came to nothing, but brought her close to Charles Mansfield, a charismatic Weybridge-based scientist and polymath, possibly (according to Joukovsky in his second TLS commentary) more important in the breakdown of the marriage than Wallis would be. Mansfield died in agony in 1855 from chemical burns received in his laboratory: if the two had indeed been in love, this would have been one of many romantic entanglements for Mansfield, and only the latest in several tragedies for her. Little Arthur had been preceded by miscarriages and still-births, and in 1851 Mary Ellen had also lost her mother, who had never got over losing a child of her own.

In fact there is every indication that Mary Ellen, a highly-strung, passionate woman herself, found the various stresses of these years quite unendurable. Catherine Horne, wife of the Victorian editor and adventurer Richard (later Hengist) Horne, spent three weeks with the Merediths in the late autumn of 1852. She sent her husband a startling account of a quarrel, during which Mary Ellen screamed loudly and seemed suicidal, only to dress for Sunday dinner with her father afterwards as if nothing had happened. "What a strange nature he must have to bear this, and still retain his affection for her," she wrote, adding, "How will it end?" (in Meredith's Selected Letters, 28).

We know how it ended. The effect on Meredith was devastating. But, true to form, and like Emilie Maceroni's writer in Magic Words, he submerged himself in his work again. Undeterred by the mainly tepid reception of his second romantic fantasy, Farina: A Legend of Cologne, he started a realistic novel, The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, while Mary Ellen was pregnant with Wallis’s child. Richard first glimpses the heroine Lucy while boating on a stretch of river with a rushing weir, in a setting very like that of Shepperton where the author’s own romance had blossomed. It also recalls the story of Emilie Maceroni's recue from the water by Edmund Hornby, for Richard Feverel too first sees his vision of delight as she slips into the Thames, and enables her to "gain safe earth" (128) — though unlike Hornby, who was on the bank, Meredith's hero is sculling, and unlike Emilie, who was punting, Meredith's heroine Lucy has simply stretched too far in reaching for dewberries on the brink.

Dusk falls on a Thames-side mooring at Shepperton.

Losing the second "Eden" that he too had found by the Thames was now a crucial part of the life-experience on which Meredith drew for his novels., but he recreated its loss most directly in his sonnet cycle of 1862, "Modern Love." The title of the sequence is a bitter one, of course, since it focuses not on union but on alienation. Far from offering fulfilment and eternal bliss, marriage, it seemed, could be nothing but a battleground, a "wedded lie." This discovery was all the more devastating for the poet because it threatened his whole vision of life in an evolving nature. Yet, much to Meredith's credit, instead of being crushed by it, he rescued something positive from it even within the work itself. In the poetry the reconciliation is still more fleeting than it had been in real life, but it is unforgettably transcendent. Rather than meeting each other as individual spirits, the two are momentarily embraced in a cosmic harmony. In his poignant Sonnet XLVII, Meredith pictures the beleaguered couple walking by his beloved river in the dusk and finding that

... in the largeness of the evening earth

Our spirits grew as we went side by side

The hour became her husband and my bride.

Love, that had robbed us so, thus blessed our dearth!

It is a moment imbued with all the beauty of the surrounding scenery, including the swallows among the willows, the sunset, and the swans:

Love that had robbed us of immortal things

This little moment mercifully gave,

Where I have seen across the twilight wave

The swan sail with her young beneath her wings.

The moment passes, as moments do. Whatever strains there were before, Mary Ellen's elopement with Wallis was the final act in the story of a fraught relationship, from which it could not recover again. The elopement dealt a humiliating double blow for Meredith. He had been "robbed" and "robbed" again, as the sonnet suggests: betrayed by both his wife and his friend. Was there any excuse for those who cuckolded him? Perhaps Mary Ellen, finding herself in a difficult marriage, turned to Wallis more for solace than love; perhaps neither wanted a long-term relationship. But these hypotheses put forward by other commentators are confounded by a letter she sent the artist that year, to be found in Mohammad Shaheen's edition of Meredith's Selected Letters. "I am always dreading to lose you because I feel I have no right to you," she wrote, "and I love you so really, so far beyond anything I have known of love" (31). She looks besotted as she gazes at Wallis in his pencil portrait of her in 1858.

Mary Ellen never recovered either her strength or her spirits after the birth of her son by Wallis. Although she went to Capri with him that year, probably for her health as much as anything, she returned alone. Her few remaining years were pitiable in the extreme. She finally settled in Oatlands, just outside Weybridge, where she died in 1861, miserably unreconciled to the fate that she had partly brought on herself. Meredith was obdurate and held out against any contact with her, and this seems cruel in view of her precipitate decline. But his second cousin and biographer, S. M. Ellis, tells us that Emilie, still living in Weybridge and now with a family of her own, acted as an "intermediary" between the estranged couple (179). This is corroborated by Mrs Bennett's dim memory from this time of a certain "Lady E — I forget her name" (qtd. in Joukovsky, "According to Mrs Bennett," 14). According to a more recent biographer, Mervyn Jones, the Duff Gordon's daughter Janet, with whom Meredith was more than a little in love, finally persuaded Meredith to let a nursemaid take Arthur to see his mother in her last days (89).

Just a few months before Mary Ellen's death Meredith told Susie Pye, whom Joukovsky has convincingly argued was Peacock's illegitimate daughter, that "it is impossible for me to see anyone who is in the habit of seeing, or is on familiar terms with, the 'opposite party'" ("A Peacock in the Attic," 14). Yet he must have exempted these kindly go-betweens, for he modelled heroines on both of them. Janet recognised herself as Rose Jocelyn in Evan Harrington, and was "thrilled at her central role," according to her mother's biographer, Katherine Frank (196). Emilie, however, made starring appearances in his much more serious works of the mid-sixties, the so-called "Italian novels": Emilia in England, later entitled Sandra Belloni, and its sequel, Vittoria. Was she "thrilled" like Janet? Although Edmund Hornby talks about his wife in his autobiography, he was not a literary man. Preferring Pope, Dryden and Goldsmith, he found contemporary writers beyond him and says nothing at all about Meredith or his works. The two men had quite different personalities; perhaps Edmund disapproved of Emilie's more flamboyant acquaintance.

Emilie must, however, have recognised herself in Emilia. Like Mary, one of her mouthpieces in Magic Words, she had a wonderful singing voice. She was also strikingly good-looking: "She had brilliant eyes, and a splendid complexion of deep, rich colouring. A superb Italian head, with dark-banded soft hair, and dark strong eyes under unabashed soft eyelids" (qtd. in Ellis 179). Meredith had already borrowed her punting accident for his hero's first encounter with his sweetheart in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. Now, whether or not he had actually seen Magic Words (which he for his part never mentions), he returned her complement with interest, and more flatteringly. His inspiration for Emilia, he told Janet in a letter of 17 May 1861, came from a real story that he had once outlined to her. Of course, he continues, "one does not follow out real stories; and this has simply suggested Emilia to me" (Letters I: 25). As so often, there is also much in his heroine that comes from his own experience: just as she has been taken into the Poole household at "Brookfield," he had found himself in Weybridge among people whose background in fashionable society he did not share. But there is no denying that the "feminine musical genius" who stars in the two novels takes her presence and passion, as well as her particular talent, from Emilie.

In the sequel, the gifted singer moves from England to Italy, where she can express herself more freely. She acquires her symbolic stage name of Vittoria and becomes a potent inspiration for the Italians in their struggle for unification and independence: "She seized the hearts of those hard and serious men as a wind takes the strong oak-trees, and rocks them on their knotted roots, and leaves them with the song of soaring among their branches" (29; a typically powerful Meredithian extended simile). That Meredith himself sympathised so profoundly with the Italian cause, to the point that he went out to Italy in the summer of 1866 as a highly partisan war correspondent for the Morning Post, no doubt owed much to his days at The Limes. He told Clodd that after the fighting was over, he "went on to Venice, where [he] wrote the greater part of Vittoria" (qtd. in Clodd 142). But Weybridge and the past were still very much in his mind as he wrote what was, after all, the continuation of a novel which drew heavily on both. One of the most haunting scenes in this sequel is that in which, instead of singing a patriotic song for Italy, the heroine sings one of her old airs, which conjures up a magical "vision of a foaming weir, and moonlight between the branches of a great cedar-tree" (348) transporting us back to the Thames between Shepperton and Weybridge, and the scenes of Meredith's first and lost love again.

Emilie, rather later in life (Ellis, facing p. 180).

Looking back, Edmund Hornby felt that his wife should probably have made a more ambitious match. He writes self-deprecatingly, saying in his autobiography that she not only had a glorious voice but was "fitted to be a leader of society" (55), much as Meredith surmised when he based Emilia/Vittoria on her. She was certainly aware of her own talent and power to move. In August 1855, she left her first-born child (her own Edith, or Edie as she liked to call her) at home with her mother in Weybridge, and accompanied Edmund to Constantinople. For all Edmund's self-deprecation, he did in fact have a distinguished career, and was being sent out to manage the loan to Turkey for carrying on the Crimean War. During the voyage Emilie entertained her fellow-passengers, including the troops on board, by playing and singing for them in the evening. She also wrote numerous letters home from the trip, vividly describing amongst other episodes the Christmas Day festivities at the Embassy in 1856. Florence Nightingale was a fellow guest, and, despite her pallor and frailty after an illness, laughed till she cried at the children's lively games (see In and Around Stamboul, 163). A visit to a harem, not the first but one of the earliest made by a western women, was another high point of Emilie's stay. These letters were put together and published by Richard Bentley in 1858 as In and Around Stamboul, and proved popular. They were republished as recently as 2010.

Meredith would surely have known about the letters at that time, just as Emilie for her part would have known of his publications. In one of her letters, she specifically asked to be sent "Mr Meredith's Eastern Tales [The Shaving of Shagpat, 1855], which I hear are very charming" (In and Around Stamboul, 124). Two such larger than life personalities, in whom the flame of life burned so brightly, were not likely to forget each other, and it was on her return from this trip that Emilie helped both Meredith and Mary Ellen in the last days of their doomed marriage. Emilie herself was to die suddenly and unexpectedly of dysentery in Dieppe on 30 September 1866, while Vittoria was still being serialised in the Fortnightly Review. Having shown how important it is for women as well as men — and indeed countries — to be given "autonomy and proper conditions for growth" (Banfield 70), and how magnificently they can respond under such conditions, Meredith writes there in his very last paragraph of his heroine's "unequalled strength of nature" (629). One wonders just how much of the vivacious, ardent and gifted Emilie Maceroni also went into the strong heroines of his later novels.

References

Banfield, Marie. RSV (Rivista di Studi Vittoriani) XI/21 (January 2006):57-74.

Clodd, Edwards. Memories. London: Chapman and Hall, 1916. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 11 December 2015.

Ellis, S. M. George Meredith: His life and Friends in Relation to his Work. London: Grant Richards, 1920. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 11 December 2015.

Frank, Katherine. Lucie Duff Gordon: A Passage to Egypt. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1994.

Hornby, Edmund, Mrs. (see Maceroni).

Hornby, Sir Edmund Grimani. An Autobiography. Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 1928. Hathi Trust. Contributed by the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Web. 13 December 2015.

Joukovsky, Nicholas. "According to Mrs Bennett: A Document sheds a new and kinder light on George Meredith's first wife." Times Literary Supplement. 8 October 2004: 13-15.

_____. "'Dearest Susie Pye': New Meredith Letters to Peacock's Natural Daughter." Studies in Philology. 111: 3 (Summer 2014): 591-629

_____. "Mary Ellen's First Affair: New light on the biographical background of "Modern Love." The Times Literary Supplement. 15 June 2007: 13-15.

_____, with Jim Powell. "A Peacock in the Attic: Insights and secrets from newly discovered letters by George Meredith." The Times Literary Supplement. 22 July 2011: 13-15.

Maceroni, Emilie (Mrs Edmund Hornby). In and Around Stamboul. Philadelphia: James Challen & Son, Lindsay & Blakiston, 1858. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California. Web. 13 December 2015.

____. Magic Words: A Tale for Christmas Time. London: Cundall & Addey, 1851. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California. Web 13 December 2015.

Meredith, George. Evan Harrington. New York: Harper, 1860.

____. Letters of George Meredith, Vol. I. Ed. William Maxse Meredith. 2 vols. London: Constable, 1912. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California. Web. 13 December 2015.

_____. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel: A History of Father and Son. London: Penguin, 1998.

_____. Vittoria. London: Constable (Mickleham ed.), 1924.

"Our Library Table." The Athenaeum. 28 December 1850: 1377. Google Books Free Ebook. Web. 12 December 2015.

Pulford, J. S. L. George and Mary Meredith in Weybridge, Shepperton & Esher, 1849-61. Walton & Weybridge Local History Society, 1989.

Sharp, William. "The Country of George Meredith." Selected Writings, Vol. IV. Ed. Mrs William Sharp. Internet Archive. London: Heinemann, 1912. 31-61. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 13 December 2015.

Last modified 13 December 2015