uskin saved me – twice. As the son of a civil servant, it was socially inevitable that I should be sent to a British public school. The (private) school was the one my father had attended, and where my mother’s father had been Vice-Headmaster, Bedford School, Bedford. I was not happy there. In the 1950s the principal values it inculcated were conformism, deference to age and power, and entitlement to privilege. There were some good teachers, music and theatre, but sporting prowess trumped intellectual interests until one finally joined the elite expected to progress to Oxford or Cambridge. I thought the place utterly philistine.

I would not have known that word had luck not introduced me to William Gaunt’s wonderful cultural history, The Aesthetic Adventure (1945). His evocation of French and English artistic and literary life from 1830 to the 1890s was the perfect alternative world to the grey limitations of a Midlands town and the petty restrictions of boarding school life. The wit, the sensuality, the cultivation of ideas, even the melancholy appreciation that this world could never be recreated, offered consolation for my adolescent alienation. Bohemians versus the bourgeoisie, aestheticism versus heartiness, difference versus deference.

Ruskin has only a modest role in The Aesthetic Adventure, chiefly as Whistler’s butt when the artist sued him for libel over his “pot of paint” comments in Fors Clavigera (Works 23.29), but dreaming of the nineteenth century kept me sane, and I read the book over and over again.

I had reason to recall the Ruskin/Whistler trial several years later, when I was invited by a friend of mine to have a lunchtime drink at the BBC. Bedford School had done its job, and I had indeed gone to Oxford, where I had spent three happy years doing as little work, and as much theatre and comedy, as possible. I left with a modest degree in history, and the intention of becoming a television director. A six month traineeship at a regional commercial television station in Southampton had taught me that philistinism was not the exclusive property of Bedford School, and I had then spent a very stimulating year studying television at an art school, Ravensbourne, but I was getting nowhere.

My friend, Leslie Megahey – a friend made at Oxford, naturally – had been more fortunate, and had secured a general traineeship at the BBC. His latest task was to produce and direct a half-hour, studio-based drama documentary for a series called Contrasts, and he was looking for a subject. During my exile in Southampton I had taken refuge in the Goncourt Journals, and proposed a recreation of one of the Goncourt brothers’ literary dinners at Magny’s Restaurant. Leslie rejected this idea as “French”. Seeing that this rare window of opportunity was rapidly closing, I suddenly remarked: “trials make good television”, and told him about Whistler versus Ruskin.

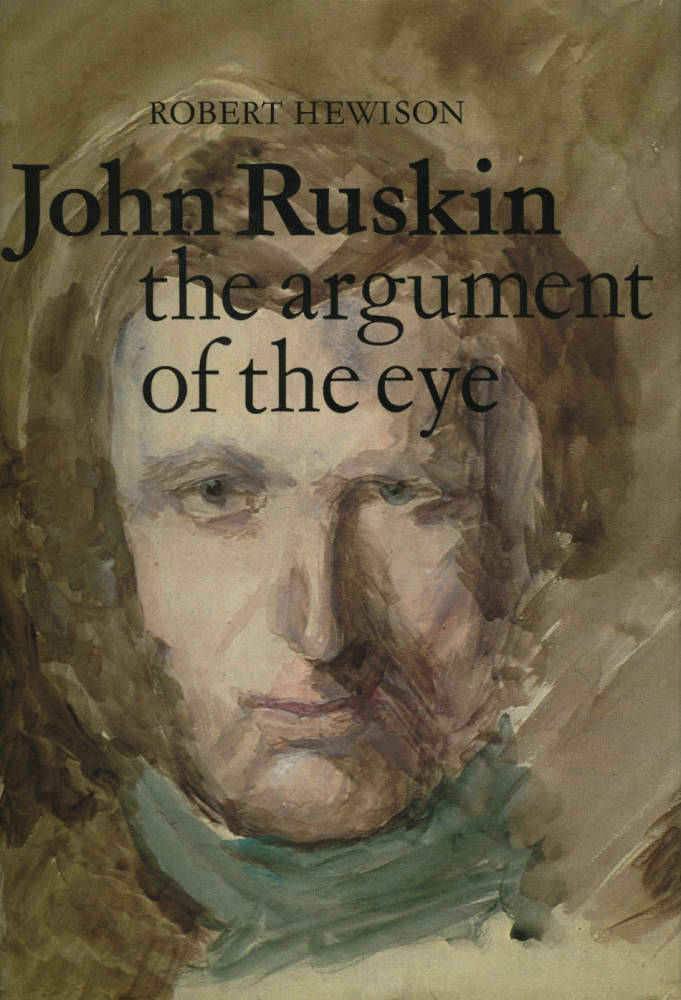

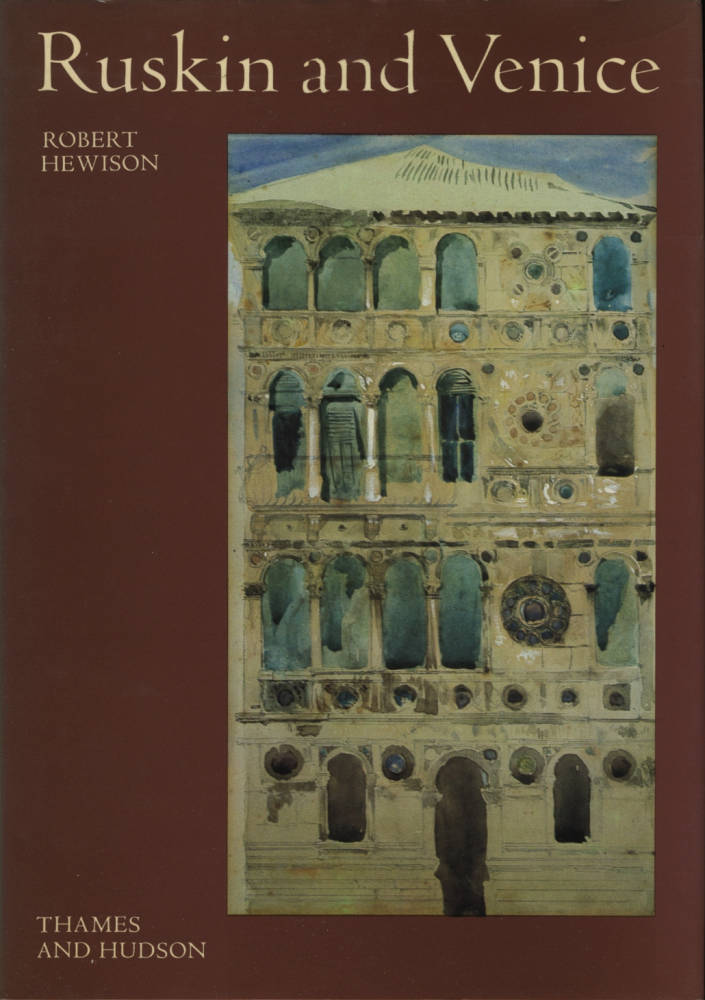

Seemingly without any of the elaborate editorial procedures that are now required, I was duly commissioned to dramatise the trial. I was fortunate in that I discovered that a lot of the trial papers were in the US Library of Congress, and obtained them on microfiche. At the Chelsea public library I encountered for the first time the weight of a morocco-bound volume of the Library Edition, and the texture of its deckled pages. I had sold the idea on the grounds that Whistler was the epitome of style and wit, and that Ruskin was a Victorian fuddy-duddy who got what he deserved, but even from the limited reading done to write the script, I began to discover something deeper, and switched my allegiance.

The programme, titled, predictably, “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies” was recorded in May 1968 and transmitted in September, with Michael Gough as Ruskin and Al Mancini – an American who had come to London with an improvisational revue in 1960 and stayed on – as Whistler. Two Oxford actor friends, who have since had distinguished careers, Oliver Ford Davis and Roland Oliver, had a line each. Leslie Megahey went on to make more arts programmes for the BBC, becoming editor of the flagship programme, Omnibus.

By the time the programme went out I had got a part-time job as one of the regular presenters of a news programme for the African Service of the BBC. This gave me time to develop my interest in Ruskin, and, seeking advice, I contacted Mary Lutyens and her husband Joe Links. They told me about a conference that James Dearden was organising at Brantwood for Easter 1969. I was invited to the conference, where, as an entertainment, we performed my script. (The late Hal Shapiro rose from his sickbed to inhabit the part of Whistler.) Rachel Trickett, Fellow in English and later Principal of St Hugh’s College, Oxford, gave a paper, and I was introduced to her. By now I was beginning to find my direction, and I asked her if she would accept me as a post-graduate. She agreed, and since I was paying my own way by continuing to work part-time at the BBC, my former college, Brasenose, gave me a place.

I never became a television director, and “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies” has long been wiped. But, to misquote Ruskin on his experiences in Turin in 1858, I came out of that television studio, in sum of several years of thought, a thoroughly converted man.

Created 18 November 2014

Images added 4 May 2019