John Pritchard

On 22 March 1853, John Pritchard, Gordon's brother-in-law, achieved his political ambition and was elected at an unopposed by-election as Member of Parliament for the borough of Bridgnorth, after the 1852 general election result in that seat had been overturned on petition due to corruption (Times, 23 March 1853, 7). He held the position until 1868 when the Bridgnorth became a single-seat constituency. Pritchard's political leanings were summarised in the Who’s Who of British Members of Parliament in which he was described as a "Liberal-Conservative, in favour of national education being extended by voluntary exertion, aided by public grants; of a reduction of the qualification in counties and boroughs; of Dissenters being relieved from the payment of church-rates; but opposed to the ballot" (Stenton). In his acceptance speech in Bridgnorth town hall, he described his political principles as being "Conservative". Pritchard and his wife took an active part in the life of his constituency. He was President of the Bridgnorth Literary & Scientific Institution, and Patron of many amateur dramatic performances in aid of funds for the Bridgnorth Infirmary.

A few weeks after his electoral success, John and Jane Pritchard were guests at a dinner hosted by John James and Margaret Ruskin at the family home at Denmark Hill. At the table were John and Effie Ruskin, Effie's lover (or lover-to-be), twenty-three-year-old John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Sir Walter Trevelyan and his wife Pauline (1816-1866), wealthy, sensitive and talented patrons of the arts and friends of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Lockhart and Cheney are also listed as being guests at dinner in John James Ruskin's diary (Ms 33, fol. 38, Lancaster). Lady Trevelyan described the dinner party as "heavenly" (Batchelor 80), and the old Ruskins as "very kind and pleasant & Effie very nice" (private communication from Batchelor). The composition of the guest list ensured that it would be interesting and stimulating. Millais, proud of being a successful and controversial artist at an early age – "only 24 in June" – provided insights into the workings of the art world, "the mean way the Academy treated him", his anger at Windus's refusal to buy paintings direct from him. Lady Trevelyan, although three years younger than Ruskin, was not afraid to criticise him for what she considered to be his "savage" treatment of people in his books: he naturally disagreed and suggested that he "ought to be ten times more so" (Batchelor 80). In spite of her forthright manner, Pauline Trevelyan and Ruskin were to become and remain close friends, and, as she lay dying from ovarian cancer in a hotel in Neuchâtel on 13 May 1866, it was Ruskin who was called to her deathbed (Batchelor 232). The chemistry and flirtation between Effie and Millais at that April dinner party would have been difficult to conceal.

John Ruskin by Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1853-54. Oil on canvas, 31 x 26 3/4 inches. Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. WA2013.67.

Three months later, the young lovers, with Ruskin, would endure a tense situation in a small rented Highland cottage at remote Glen Finlas for the month of July 1853. Millais' task was, he informed William Holman Hunt, to "paint Ruskin's portrait by one of these rocky streams" (Batchelor 86). The weather was cold and wet, and made the huis clos situation even more intolerable. Effie's escape from her loveless, sexless marriage would take place nine months later.

Jane and John Pritchard were again guests at Denmark Hill on 1 June (Ms 33, Lancaster). This time the company included thirty-one-year-old Scottish landowner, William Macdonald (1822-1893), described in Praeterita as "a thin, dark Highlander" and "the son of an old friend, perhaps flame, of my father's, Mrs Farquharson" (35.423-424). Macdonald had been best man at John Ruskin's wedding (Hilton 112). John James's business partner Henry Telford and the artist brothers George and Thomas Richmond were also present. Yet another invitation was accepted by Jane and John Pritchard on 25 June (Ms 33, Lancaster).

Meanwhile, during the summer of 1853, Osborne Gordon was entertaining to dinner at Christ Church a visitor who would have an enormous impact in the world. He was dining with Andrew Dickson White (1832-1918), an American historian and educator, and future co-founder, with Ezra Cornell, of Cornell University. White had just completed his undergraduate studies at Yale, and was on a three-year study visit to Europe, at the Sorbonne, at the University of Berlin, and at the American Ministry in St Petersburg. White was much influenced by the early works of Ruskin, in particular The Seven Lamps of Architecture (complete text). One likes to think that Gordon had some input into the creation of Cornell University. White recorded, all too briefly, in his Autobiography, his impressions of Gordon:

At the close of my undergraduate life at Yale I went abroad for nearly three years, and fortunately had, for a time, one of the best of companions, my college mate, Gilman, later president of Johns Hopkins University, and now of the Carnegie Institution, who was then, as he has been ever since, a source of good inspirations to me,— especially in the formation of my ideas regarding education. During the few weeks I then passed in England I saw much which broadened my views in various ways. History was made alive to me by rapid studies of persons and places while traveling, and especially was this the case during a short visit to Oxford, where I received some strong impressions, which will be referred to in another chapter. Dining at Christ Church with Osborne Gordon, an eminent tutor of that period, I was especially interested in his accounts of John Ruskin, who had been his pupil. Then, and afterward, while enjoying the hospitalities of various colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, I saw the excellencies of their tutorial system, but also had my eyes opened to some of their deficiencies. [White I, 34]

In the Ruskin family circle, events moved swiftly between the summer of 1853 and April 1854. As Effie became increasingly estranged from the Ruskin family, so her closeness to her own family and to Cheney and Brown increased. Secrecy in planning her release from Ruskin was paramount. Cheney proved to be a loyal friend to her. On the surface, things appeared normal. In late November 1853, Effie and John were invited to stay again at Badger Hall with the Cheneys. Effie wanted to accept but John refused as she explained to Rawdon Brown: "I would have very much enjoyed a couple of days with our kind friends at Badger, and they wished it, but John is not inclined" (Lutyens2 113).

Dinner parties continued as normal at Denmark Hill. In mid-January 1854, John James noted in his list of guests John and Effie, Gordon, George and Thomas Richmond, and others (Ms 33, Lancaster). The older Ruskins continued to consolidate their relationship with the Pritchards, and invited them to their home for dinner on Tuesday 28 February, along with Gordon and Charles Newton, but seemingly without Ruskin (Ms 33, Lancaster). On learning of this arrangement, Ruskin immediately and high handedly cancelled an invitation he and Effie had accepted to dine with Lady James, informing Lady James that Effie would go alone. Ruskin preferred to be with his parents, the Pritchards and his two Christ Church friends. He did not consult Effie: she refused to go on her own to Lady James's (Lutyens2 145). In retaliation for what Ruskin considered to be Effie's unacceptable behaviour, he ordered her to either "stay here all the summer alone or go to Perth", for he was planning another long continental tour with his parents.

On 5 April 1854, the Pritchards dined again with Mr and Mrs Ruskin at Denmark Hill (Ms 33, Lancaster). Other guests were the Rev. Thomas Dale (Ruskin's former tutor), evangelical vicar of St Pancras, London, and his son Lawford. Effie, her eleven-year old sister Sophie (a shrewd observer of the Ruskin household), and Effie's devoted Scottish friend Jane Boswell were also present. It must have been a strange and strained occasion. Effie was in a nervous state and suffering from terrible pain. Wine flowed freely, to such an extent that "old Madam" (Mrs Ruskin) became inebriated and descended into vulgar conversation. Effie provides a fascinating insight into a little-known aspect of Mrs Ruskin's personality: "Jane is perfectly rabid on the subject of the R's, especially Mrs R. She was so disgusted with her conversation last night that she thinks she must have been quite drunk" (Lutyens2 168).

Tension was increasing between Effie and her husband. She confided fully in Rawdon Brown and Cheney who did not betray her secrets. Ruskin insisted on working and dining with his parents at Denmark Hill: it was, he told Effie, "absolutely necessary". Life was "a perpetual struggle" (Lutyens2 174), a battle of the wills between the incompatible couple. Effie could no longer tolerate Ruskin's hypocrisy, and that of his parents. She revealed to Rawdon Brown Ruskin's true feelings about the "kind friends" the Cheneys: "As for John, he is as hypocritical about the Cheneys as in other things. He says they are intensely worldly, know nothing about Art etc, but as he thinks everybody who does not flatter him mad or bad – this is not singular" (Lutyens2 176). Ruskin was becoming more and more selfish and intolerant – that was Millais' opinion (Lutyens2 178).

Plans were being put in place for Effie's departure. Her parents arrived in London on 14 April, took legal advice and made appropriate arrangements for the separation. Almost on the eve of the continental journey from which Effie was excluded, Ruskin said goodbye to her at King’s Cross railway station, London, on 25 April 1854. He had, seemingly, no suspicion that she was planning to leave him and would never return. She left for Scotland and the home and care of her own family. Later that day, a citation was served on John Ruskin. Effie returned her wedding ring, keys and accounts book to Mrs Ruskin and enclosed a letter informing her of the impending divorce and the reasons for it. Effie severed all relations with the Ruskins and decisively signed the letter "Euphemia C. Gray" (James 227).

Ruskin’s marriage was annulled on 15 July 1854 on the grounds of non-consummation. He was conveniently in Chamonix at the time with his parents and was to remain abroad until the beginning of October. Liberated from the strain of his marital situation, and back in the familiar family triangle, Ruskin pursued his work with renewed vigour, preparing materials for the third and fourth volumes of Modern Painters.

Meanwhile, Gordon was preoccupied with other things, in particular the constitution of Christ Church. He argued his case for change with W. E. Gladstone, also a Christ Church man, who, in 1854, was both Chancellor of the Exchequer and MP for Oxford University. Gordon believed strongly that Fellowships at the College should be earned and based on merit and achievements. He explained his strong personal feelings in a letter to Gladstone of 11 April 1854 now in the British Library: "I was appointed by the Dean unasked and without any knowledge – and I felt at the time and ever since that the college had acquired a right to my services, such as they are. But if I had been appointed, for instance, after I obtained the Ireland scholarship, I should have considered that I had earned it by fair examination, and felt under no obligation to any one" (Add. Ms. 44379, folio 288). The correspondence to hand on the matter of scholarships and studentships begins on 21 March 1854 and demonstrates Gordon's commitment to his principles and his relentless pursuit of the matter in the face of opposition, and some criticism from Gladstone who had accused him of being too negative. Gordon's overriding concern for the welfare of Christ Church undergraduates and staff is paramount. At one point he only pauses to take "a week's tour in Normandy" just after Easter in April 1854 (BL Add. Ms. 44379, folio 226).

That same year marked the marriage of Gordon's brother William Pierson Gordon, a solicitor, to Anne Hunt. John and Jane Pritchard, who remained childless, were close to William and his family, and particularly fond of his only son (their nephew) William Pritchard Gordon who inherited much of their estate on their death. (Four girls were also born: Jane Gordon (died in 1912), Clara Gordon, Hilda Gordon and Agnes Isabel Baker.) William's middle name of Pritchard is both an acknowledgement of his grandmother's maiden name and his uncle's family.

Shortly before Christmas Jane and John Pritchard celebrated the festive season at a small party at the Ruskins' house at Denmark Hill to which the Rev. Daniel Moore and his wife – travelling companions abroad in 1851 – the two Richmond brothers and Mr and Mrs Fall were invited (Ms 33, Lancaster).

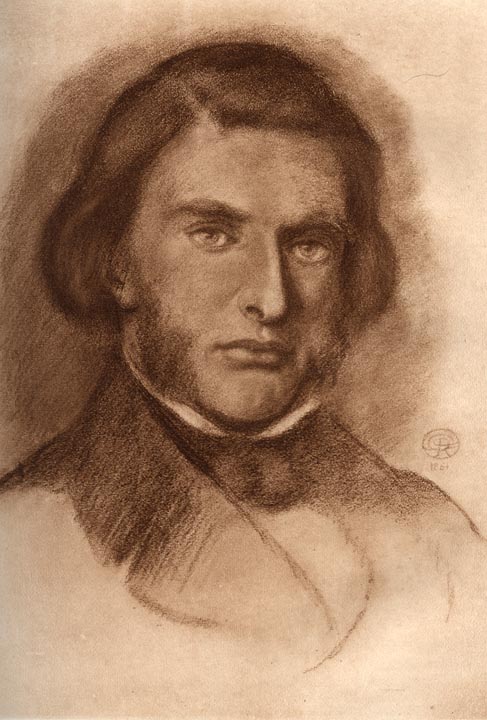

John Ruskin by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 36.26.

Ruskin did not go abroad in 1855: work was his priority and unnecessary social invitations were refused. In a letter to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, he explained: "I am deep in difficult chapters of Modern Painters. I cannot be disturbed even by my best friends or greatest pleasures" (5.xlvii). This was not entirely true, for there were numerous invitations. The Poet Laureate, Alfred Lord Tennyson was invited to Denmark Hill to view Ruskin's Turner collection. Gordon remained close to the Ruskins, and on 14 April, he was invited to the family home where he was introduced to Coventry Patmore (1823-1896), poet, critic, reviewer of Modern Painters II and The Stones of Venice, and writer of articles on architecture with views at times opposed to Ruskin's. In February 1854, he had praised the new style of railway architecture and wrote: "What can be more pleasing [...] than the light iron roof, with its simple, yet intricate supports of spandrels, rods, and circles, at Euston square, or the vast transparent vault and appropriate masses of brickwork at King's Cross?" (quoted Brooks 101) George Richmond, and Edmund Oldfield with whom Ruskin had collaborated on the stained glass windows for St Giles's Church, Camberwell, were also present. In this stimulating company, against the background of Ruskin's Turner collection, the conversation ranged from art, religion, architecture and the battle of the styles, to poetry and church windows.

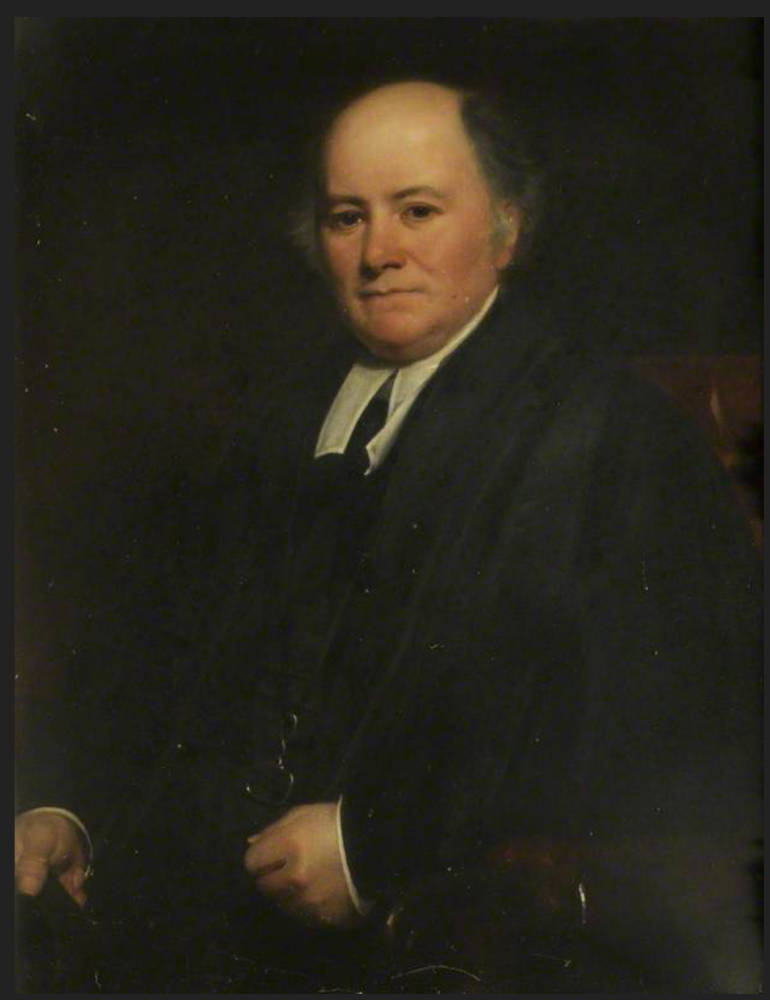

Thomas Gaisford (1779-1855) Henry William Pickersgill (1782–1875. c. 1847. Oil on Canvas. 88.9 x 69.9 cm Courtesy of Christ Church, Oxford LP 264 and ArtUK

Although Liddell’s temporary departure had facilitated Gordon’s career in 1846, his return to Christ Church as Dean in 1855, a hasty appointment not without controversy, precipitated Gordon’s leaving. Dodgson recorded in his diary of 7 June 1855: "The Times announces that Liddell of Westminster is to be the new Dean: the selection does not seem to have given much satisfaction in the college" (Carroll Diaries 101). The previous incumbent, Thomas Gaisford (1779-1855), Regius Professor of Greek, had been Dean since 1831. For Ruskin, whose undergraduate drawings had been so admired by Gaisford (Burd II, 450), he was England's "greatest scholar" (35.192). John James Ruskin had shown his gratitude to Gaisford for helping his son by sending him a hamper of thirty-six bottles of rare vintage sherry of 1823 (Burd II,734). Gordon was particularly close to Gaisford, his "chiefly trusted aid" (35.251). His sudden and unexpected death at the age of seventy-seven caused much sorrow. Dodgson wrote in his diary of Saturday 2 June 1855:

This day died our old Dean, respected by all, and I believe regretted by very many – only Saturday last he was with Mr Gordon and myself in the Library, putting away the new books, and apparently in perfect health: little did I suppose that was the last time I should ever see him – all this morning they have been issuing bulletins hour by hour: the one announcing that all was over came out about half past 11. [100]

On the death of Gaisford, Gordon delivered a lengthy funeral oration, in Latin, that was "worthy of the best days of Roman eloquence" (Marshall 41).

John Pritchard was now on Royal guest lists, and, as The Times for 15 June 1855 reported, he was invited by Queen Victoria to a "Drawing-room" – a court reception – in St James's Palace on the afternoon of Thursday, 14 June 1855. Similar invitations were received in subsequent years. Gordon, too, was on the Royal guest list of the Prince of Wales (whom he tutored at Christ Church in 1859), and was invited to several all male receptions, called levées, at St James's Palace on 26 June 1868, 1 June 1869, 11 March 1878, and on 3 May 1879 with his brother-in-law, John Pritchard. On another occasion in July 1872, Gordon was invited by the Prince and Princess of Wales to a garden Party at Chiswick.

“The Serjeant.” Sir John Simon ('Statesmen. No. 500.') — Vanity Fair’s 1886 caricature.

Ruskin wanted to introduce the Pritchards to his own circle of friends, away from Denmark Hill. So he arranged for them to meet his new friends John Simon (1816-1904) and his Irish wife Jane (née O'Meara, born 1816, died 1901). Dr Simon (Sir John from 1887) was a medical doctor who, in 1855 had been appointed to the new post of Medical Officer to the Privy Council. He was also the first Medical Officer of Health for the City of London, appointed in 1848, and had a particular responsibility for the prevention of cholera and other public health issues. Ruskin was concerned that the threatened dissolution of Parliament – it was dissolved in March 1857 – would thwart his plans. At first he thought that Pritchard would have to be out of London, campaigning in his Bridgnorth constituency at the time of the proposed meeting with the Simons. But all was eventually arranged and confirmed in Ruskin's letter to Mrs Simon: "I did not answer your kind note, because the threatened dissolution of Parliament might have sent Mr Pritchard and his wife, whom we wanted you to meet, into the country again, – but as matters are now arranged, they are coming, and if you can come too, it will give us all very great pleasure" (36.256-57).

The voice of the leading art critic of the day was eagerly awaited at the Royal Academy Exhibition that opened in early May. Within a few days, Ruskin's Notes on some of the Principal Pictures Exhibited in the Rooms of the Royal Academy and the Society of Painters in Water-Colours etc. had to be completed, published and made available to the public. Budding art collector and connoisseur John Pritchard attended, along with John James Ruskin on 5 May 1857 (Ms 33, Lancaster). There they saw works by John Everett Millais (about whom Ruskin was uncomplimentary), Naftel (whose Paestum Pritchard would purchase a few years later), Clarkson Stanfield, E. W. Cooke, J. D. Harding (Ruskin's former drawing master), Pierre Édouard Frère and many, many others. In June, Ruskin's Elements of Drawing was published. It was a manual and practical guide, made up of much of the material that Ruskin used in his classes at the Working Men's College, London. On 8 December 1857, John and Jane Pritchard were invited to Denmark Hill along with Dr Grant, Harrison and artist Tom Richmond (Ms 33, Lancaster).

Towards the end of 1858, Ruskin became an Honorary Student of Christ Church. This was a great honour – he was only one of ten elected at the time – and due to the influence of Gordon who put his name forward, seconded by the Dean. Other Honorary Students elected at the same time were W. E. Gladstone, Sir George Cornewall Lewis, Sir Frederick Ouseley (Professor of Music), Dr Acland, Henry Hallam, Lords Stanhope, Elgin, Dalhousie and Canning (Bill and Mason 96).

Last modified 10 March 2020