Prologue

This essay first appeared in the Ruskin annual, The Companion (2013): pp. 42-47. I am grateful to The Guild of St. George for permission to republish it here. Minor changes have been made.

s the short essays which would soon be collected into Unto This Last (the only book among his dozens that Ruskin would ever describe as a “true book”; that is, a book true from first word to last), printed serially in London’s Cornhill Magazine in 1860, the editor, the famed novelist, William Makepeace Thackeray, started to receive, first a few, then an avalanche of letters from the prestigious magazine’s readers vehemently protesting against the economic practices the author of the essays was proposing. “Balderdash,” wrote some, “impossible,” said others, “lunacy,” said still others, “the preachings of a mad governess,” wrote one particularly incensed reviewer. Indeed, the uproar became so great Thackeray was finally forced to tell Ruskin that the Cornhill would not welcome the earlier agreed-upon three remaining essays in the series, although, he said, in an attempt to mollify his furious author, he was allowed by the publishers to let Ruskin have one last, double-length essay.

Responding in his “Preface” to Unto This Last in 1862, Ruskin expressed his surprise that his economic essays had been “reprobated” in so “violent” a manner. For at the heart of all his counsels lay a very simple notion: that in all our economic dealings we should be honest, that it was never our business to trick or cheat or harm one another, never our business to put our own personal interests above those of anyone we traded with. Indeed, economic exchange was no different than any other occupation, a way for those who could produce something we needed to produce it for us as efficiently and cheaply as possible. The truly great tragedy of the modern world, Ruskin said, was that we have lost our “faith in common honesty and in the working power of it” for good. Without such faith, civilization starts to crumble, and we start to regard each other as enemies rather than as associated helpers along life’s path that all logic and religious teaching instruct us to be. Hence, he concluded, “it is quite our first business to recover and keep” this commitment to honesty in the modern context. It was the intent of Unto This Last to demonstrate this verity beyond any reasonable doubt.

Two years later, in 1864, Ruskin’s father, the very rich and successful sherry merchant, John James Ruskin died. He was buried in Shirley Churchyard, near Croydon, south of London. On his sarcophagus, his son engraved the words below, words of tribute that, we trust, any merchant would be proud to have carved on their own gravestone as an enduring acknowledgement of how they conducted their life’s work:

John James Ruskin

Born in Edinburgh, May 18th, 1785.

He died in his home in London, March 3rd, 1864.

He was an entirely honest merchant,

And his memory is, to all who keep it, dear and helpful.

His son, whom he loved to the uttermost

and taught to speak truth, says this of him.

The First Library Edition

t was 1994, and, after paying my respects at some significant Ruskin sites, including Brantwood and the Ruskin Gallery in Sheffield, I had traveled to London for a day before flying back to the US. At the heart of those 24 hours would be a chance to meet Clive Wilmer whom I had first met in 1989 in Cambridge after reading his excellent (still excellent; still in-print!) compilation of some of Ruskin’s most important writings on society, Unto This Last and Other Writings. Our plan was to go to the National Gallery to study together its small collection of permanently hanging Turner oils using Ruskin’s lengthy descriptions of these masterpieces as our interpretive guide and food-for-talk. The descriptions, complete with marvelous reproductions and introductions, had been published not long before by Dinah Birch in her book, Ruskin on Turner (this book, alas, is now out-of-print, but good copies can often be found on the web). It turned out to be, of course, a thrilling afternoon and, when our Ruskin-Turner stroll was finished, Clive and I decided to celebrate with a pint (perhaps two!) in a pub on the edge of Trafalgar Square.

A page from Unto This Last in the Library Edition.

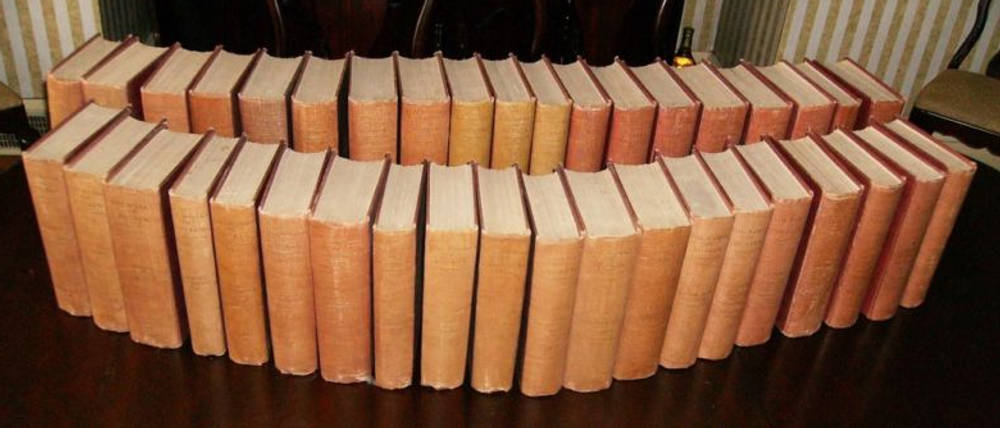

By now very much committed to Ruskin studies, it was not long before I lamented to Clive how frustrated I had become by my inability to find a full, 39-volume set of E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn’s Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin (1903-1912). Since 1989 I had been the happy possessor of the three Library Edition volumes containing Ruskin’s Fors Clavigera letters “to the Workmen and Laborers of Great Britain,” these having been found by my late wife, Tracy, in a Bloomsbury book shop and presented to me as a Christmas present. Reading the Fors volumes closely taught me how indispensable it was to have a complete version of this remarkable collection to hand when doing any serious Ruskin reading or research. Not only were the volumes impeccably produced on high quality paper with easy-to-read type, every page had been copiously footnoted by Cook, making cross-referencing to other passages in other volumes easy while explaining, in other notes, Ruskin’s then-current, but now arcane, references to classical sources, or journals or books of the day. Unfortunately, such a set was not to be found in any antiquarian bookshop in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York where I lived. To make matters worse, searches on library list-serves and the then-fledgling internet proved useless: there were either no Library Editions for sale or those that had made it to the market were well-beyond the means of a liberal arts university professor (not infrequently $10,000 or more).

It was at this point that Clive said: “Jim, I know where there’s a Library Edition you might buy.” Dumfounded, I asked: “Where?” “In Cambridge,” he said. “There’s what we call a ‘minor’ public school there—Americans would think of it as a ‘private’ school—The Leys School. They have a set they are hoping to sell. The set’s been in their library for a long time and it’s rarely used. In fact, it may never have been used; Ruskin’s been out of intellectual fashion for a long time. My friend, Charles Moseley, can tell you about the set. Shall we ring him up?”

And so it happened that, before five new minutes had passed, with my nerves jangling as coins dropped into the public phone at our pub (no cell phones in those days!), I found myself speaking to the good Dr. Moseley. “Yes,” he said, “it’s available, all 39 volumes, and it’s in fine shape. We’d need to have £1000 for it, however. Are you interested?” Was I interested? Not only was the Library Edition the Holy Grail I needed to do my Ruskin studies well, it was “in fine shape” and was being offered at a price at least three (and, as often, five or six) times cheaper than the few sets I had found on the web!

But the immediate problem was that I had a 4 PM departure from Gatwick Airport the following day and it was already late in this day’s afternoon! No matter, I told myself. I will find a way to do this! But how was I to pay for the treasure? I had nothing approaching £1000 with me and, in those days, bank machines dispensing large amounts of cash didn’t exist. Explaining this to Dr. Moseley on the phone, I felt that my chance, perhaps the only one I’d ever have, to buy a Library Edition I could (if barely) afford, was slipping away. “It’s no problem,” Dr. Moseley said, “If you are a friend of Clive’s, we’ll trust that you’ll wire us a certified check when you are back in America.” Pleased beyond words at this kindness, I told Dr. Moseley that my rental car and I would be at the Leys library door at 9 AM the next morning. Exhilarated, once I had hung up the phone, I thanked Clive profusely. He said he was more than happy to help. Then, as he headed back to Cambridge by train, I spent the following two hours spreading maps of Southern England on tables around the pub asking anyone and everyone what would be the quickest traffic-dodging route to Cambridge, following this query with another attempting to determine what would be the fastest route to get me from Cambridge to Gatwick.

It was beautiful; one of the maroon-covered sets, almost perfect in fact—the covers intact and tight, the pages—oh, my goodness!—at least in all the volumes I thumbed through (about a dozen), uncut! Clive had been right: the set had never been used! The only “blemish” (minor!) was that the spines of some volumes had faded as a result of their regular encounter with afternoon sunlight as the decades passed.

But, immediately after my initial rush of excitement had passed, a problem presented itself: how was I to get all these books on the plane? Dr. Moseley, who, from the first, had been delighted with my delight, had the solution, he said. He quickly left the room, to return minutes later with four large cardboard boxes, into which we speedily—but carefully!—packed my three just acquired Very Important Misters: Cook, Wedderburn—and Ruskin! But it was now close on ten-thirty. After thanking Dr. Moseley exuberantly (I really wanted to hug him, but refrained; we were, after all, in England, and I had just met him!), my car and I drove, at whatever reckless speed I was willing to brook, toward Gatwick, my cornering ability much enhanced by the weighty contents in the rear seat and boot.

“You say that these boxes are filled with books?” the lady at the British Airways ticket counter asked her breathless customer? “Yes.” “Books by…?” “By John Ruskin.” “Who?” “John Ruskin. He was a very important British writer of the last century.” “Well, I never heard of him. Did he really have four boxes worth of things to say?” “Absolutely.” “Hmm…But then why is it, if he wrote that much, that I never heard of him!” “Well, actually, I could answer that question, but it would take some time and I’ve only got a half hour until my flight lifts off.” “Yes, I see that. All right, but I want you to know that this is highly irregular. I’ll let these go, but it will cost you £20 per box for extra baggage.” Credit card immediately on the counter. “But I’ll tell you this,” she called after me as I sprinted for the gate, “I don’t think you’re going to have an easy time of it at American customs!”

“What’s in the boxes?” the customs agent in Newark, New Jersey, asked. “Books,” I said, and then, trying to anticipate the next question, added: “Books by John Ruskin, an important British writer of the last century. These are his collected works, very rare.” (Mistake First!) “Never heard of him. How rare and how valuable a set is it? You may have to pay import duty.” “Ah…well, actually, they are really not all that valuable, I only paid £1000 for them.” “How much is that?” “Oh, sorry. It’s about $1800, perhaps slightly more these days.” “That’s way more than your allotment. You are only allowed, as you know, as I see on your passport that you’ve been to England often, $400 in duty-free items.” “They are all for scholarly use, sir. I’m not really a book collector and I’m certainly not a book seller.” “All right, if that’s the case—and I can see from your passport that you are a professor—I guess I can let you go without paying duty. Where’s your receipt for the purchase?” Panic! “Ah…well…you see, I actually don’t have a receipt. I made an agreement with a man at the English school where I bought them to send payment when I got home.” “Then, for all I know, you might have paid five times as much for them.” More panic. Then inspiration: “Look, while I can’t prove how much I paid for the set, let’s open one of the boxes, even all of them if you like, and I can show you that they all have the bookplate of the school, a small school in Cambridge and not a wealthy one.” (Mistake Second!) “How do I know it’s a poor school? Isn’t Cambridge University there? And isn’t it one of the richest schools in England?” he asked, immediately seeing the flaw in the professor’s rattled reasoning. “Wait here.” Then he’s gone. This followed by ten minutes of escalating nervousness and worry that I was going to be forced to leave my priceless Library Edition in a customs warehouse somewhere in New Jersey, leave it until that time when, after posting payment to Mr. Moseley and getting back acknowledgement that the money had arrived, I could go and collect them following a six-hour drive back to Newark. Finally, the agent comes back: “I talked to my boss. Take your damn books and get out of here. But know that we’re cutting you a lot of slack on this, Mr. Professor! Know too that we’ve put a note in your file. So, if you ever try this sort of thing again, we’ll confiscate whatever it is you are bringing in!” Then, sardonically, as I wheeled my cart toward the exit: “Enjoy your Ruskin! Whoever he is!”

Home. Geneva, New York. Relieved. Tremendously pleased. Tracy pleased for me. The certified check sent via Western Union to Dr. Mosely at Leys next day; followed by, on the second day, a visit, all four boxes in tow, to the Archives at Hobart & William Smith Colleges, where I meet my good friend, the Colleges’ Archivist, Charlotte Hegyi, to show off my treasure; she more than a little familiar, as are all the staff at the library, with my love of Ruskin. “All the pages are uncut!” Charlotte says as she pulls first one volume and then another out of the boxes. “How are you going to use the books?” A tiny point. One that had not occurred to me during the frenetic days just passed!

“How many volumes are there?” Charlotte asked, seeing my consternation. “39,” I said. “And how many pages in each?” “Well,” I said, “it varies a bit, but usually at least 500!” “So, that means that the set has about 17,000 pages, which in turn means, allowing for some variance in one direction or another depending on any given volume, that, if you are going to use these books, given that each cutting frees four pages, that something like 4300 cuts have to be made!” My heart sinks.

“Oh, I’ll do it,” Charlotte says after a pause. “I know how to do it properly and have the right tool.” “You are such a good soul,” I say, delighted and enormously relieved, “but can’t you get your student workers to help?” “Not a chance,” she says: “They are often careless and this needs to be done carefully.” And thus, Charlotte, already high in my personal pantheon for her sweet friendship, rises into my realm of heroes for bestowing a kindness neither expected, imagined, or perhaps deserved, a generosity honored in my thoughts every time I reach behind me in my carrel in the library to take down a volume of Cook and Wedderburn to read, check some detail, or just to peruse the wondrous contents.

After leaving the 39 volumes with dear Charlotte, I head up to my carrel, the special space where all my Ruskin work is done. As I turn the key in the door, for the first time, this disturbing thought occurs: “Wait a minute! Clive doesn’t have a Library Edition, and he loves Ruskin as much as I do! He lives in Cambridge and knew the set was available and, to boot, had Mr. Moseley’s phone number readily available! Why didn’t he buy the set?” Which was followed by another thought, in answer: “Oh, my goodness! He didn’t buy it because he didn’t have the money! I have what should have been Clive’s Library Edition! Unable to buy it himself, he ‘gave’ it to me out of kindness and friendship, never mentioning the disappointment he must have felt when he saw my excitement and gave me Mr. Moseley’s phone number.” And in this way, I came to the realization that that which I had been seeing solely as my fors-aided good fortune had been something far beyond and more laudable than that: it had been a selfless gift.

The Second Library Edition

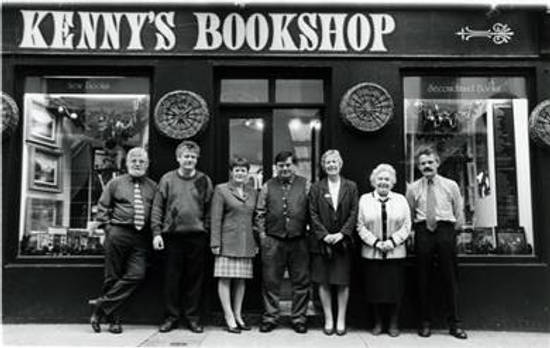

Kenny’s Bookshop in the Galway High Street, 1990s: L-R: Tom Kenny, Gerry Kenny, Monica Rigney, Des Kenny, Jane Hogan, Maureen Kenny and Conor Kenny/

t was a year later, the fall of 1995. I am leading a semester-long program for my students in Galway, Ireland. Naturally, it is only a matter of days before I am on the hunt for the best bookstores in town. Asking, I am repeatedly told that Kenny’s Bookshop in the High Street is not only the best in the city but is, in many estimates, arguably the best in Ireland.

Always on the lookout for Ruskin or Ruskin-relevant titles (even with a Library Edition there is much else one needs!). Inside, I am greeted by Des Kenny, one of the store owners: “Welcome to Galway, Professor. Call me Des.” “Any Ruskin, Des? Call me Jim.” “Well, Jim,” the Irish eminent replies, “to tell the truth, we don’t get much call for Ruskin these days, but you can try upstairs and see if there’s anything under art or architecture.” There is, as Des says, not much—a couple of “George Allen Greens” (cheaper versions of Ruskin’s works), a tattered copy of Kenneth Clark’s marvelous compendium, Ruskin Today (which I already own in better condition). I report back to Des. “I’ll keep a lookout for you, Jim,” he says. “You never know what might come in. Give me your phone number and if anything does, I’ll call.” As I turn and start to leave, I hear this from Des, behind me: “I don’t know if you know it, but we have a huge collection of used books in our store out back, just across the street. I don’t know if we have any Ruskin, but you are welcome to poke around.”

In minutes, I am poking. In the shop in the back, there are at least a hundred bookcases chock full of earlier owned titles. Checking by section, I find there is nothing of Ruskin’s under art, nothing under architecture, nothing under society; nothing any place: in short, a dead end. But wait! Over there, on a wall of mixed books near the cash register, I see a familiarly-sized volume with a blue cover—about two and a half inches wide and ten inches high. Could it be a volume of the Library Edition? It is, amazingly enough! Volume 13, as it happens, which contains a swath of Ruskin’s writings on Turner—in very good condition. “May I take this to show Des?” I ask the clerk. “Sure.”

“Des, look at what I found,” I say once I am back in the main store, already thinking of Clive and my fervent wish, if ever it proved possible, to redress the “wrong” of the year before: “It’s a volume of the great set of Ruskin’s works. Are there anymore?” “I don’t know, Jim, if you didn’t find any others out there, it’s probably a stray.” My heart descends. “Hold on,” Des says some seconds later, “we have a warehouse with thousands of boxes of books not far from here. Maybe we can find a few more volumes if we search there. I’ll get my staff on it right away. Check back tomorrow.”

Tomorrow: “Jim,” Des says as I enter Kenny’s. “Guess what? We found a dozen more volumes in various boxes, scattered all around the warehouse. How many volumes are there in the set?“ “39,” I respond. “OK, let me keep hunting. There may be more. Why don’t you go to the store out back and look at those we found? They’re lined-up on the floor near the register.” I go; Des comes too. I start checking: the Library Edition volumes, now 13, are in, if not perfect, then fine condition—most of the spines are tight, the plates pristine (some marginalia in a few volumes). I am delighted. “Come back tomorrow,” Des says. Hope!

Tomorrow: “Come with me,” Des says excitedly as I enter. “Look!” He smiles as we arrive at the top of the stairs by the cash register in the backstreet shop. My heart leaps! For there, lining the floor, is what has to be a complete set of the Library Edition, all the volumes which have been added since the day prior seemingly as unspoiled as the others. “I told you we had lots of books in the warehouse,” Des says. “My staff found these in other boxes. I don’t know why they were separated, where we got them, or when, but here they are! Remind me how many volumes there are?” “39.” “Ah, well, there’s a bit of a problem then,” Des says. ”I thought 39 was the number. But, as it happens, we have only 38 and, even doing a double search, we couldn’t find that last one. Somehow, it’s gone missing.” “Which one is missing?” I ask. The volumes on the floor being unordered we rectify the situation and discover that Number 35 is missing. Number 35? Praeterita! Ruskin’s autobiography, one of the most important volumes in the collection! But still! Here, in front of me, stand 38 volumes in superb shape. “Des,” I say, “OK, so we have an incomplete set. It’s not for me. It’s for a dear friend in England who very much wants this set and, in truth, needs it for his Ruskin research. How much do you want for what’s here?” Des thinks about it for a few moments. “How does £325 sound?” “Amazingly good, amazingly fair,” I reply. “Let me get to my friend and see if the price is OK with him. Can you hold them for a few days? I’m not quite sure how long it will take to work this out.” “Sure,” says Des. “They’ll stay right here until I hear from you.”

Calls to Cambridge. No answer. More calls. More no answers. Clive finally reached at home that night. All explained, the set, its fine condition, Praeteritamissing, my great delight at finding a set for him. “Let me make a few calls and I’ll get back to you, Jim. It might take me a couple of days.” “Fine,” I say, “Des said he’d hold them until I hear from you.” A day passes. Another. Finally, on the third day, Clive calls and says happily: “Let’s do it! I’ll work out the details of payment and shipping with your bookstore man.”

It being around noon, ten minutes later, I’m at Kenny’s. Des not at his desk. “Where?” “Out back, in the other shop.” Mounting those back stairs, I immediately notice that the Library Edition is no longer on the floor! Seeing my man near the register, I ask: “Des, what’s happened to the set? My friend in Cambridge has said yes. He very much wants it.” “Funniest thing happened after you left the other day, Jim,” Des replies. “You won’t believe it! Less than an hour later, a fellow from Dublin came in, saw the books on the floor, came to find me, and asked about them. I told him that they were on hold for another customer. He asked me what price I had asked for the set. I told him £325. He said that he had been looking for a set of this edition for twenty and more years and that he was willing to pay me £1500 in cash right now if I would sell them to him. (My heart nearly in my shoes at this point.) I told him one volume was missing. He said it didn’t matter. He’d buy the set as is. It was, as you might imagine, Jim, a very tempting offer, almost five times as much money, capital we very much need right now in the business. It’s not every day we make £1500 sales here, you know. But,” he went on, seeing my distress, “I told him that I just couldn’t do it. I had made a promise to another customer and until that customer told me he wasn’t interested, I couldn’t in fairness sell the set to someone other at any price. An agreement is an agreement. He wasn’t pleased! He even offered me another £100! But I refused once more. He was furious when he left! But he gave me his phone number just in case your friend changed his mind.”

My now immensely grateful heart now back in its rightful position, I grasp that, not only was this unexpected Galway Library Edition going to become Clive’s, but that Des Kenny, who didn’t read Ruskin, who hardly knew who he was in fact, by refusing the much larger offer and brooking the ire of an obviously well-heeled collector, had acted exactly as Ruskin argued all merchants should act, had done in practice exactly what an entirely honest merchant should do—put the well-being of your customers first and hold to it come hell or high water.

“Clive Wilmer and Jim Spates in Venice, 2008

“But, Des,” I asked, “if this is all true, as I am sure it is, where’s the set? When I didn’t see it on the floor and you began your story, I thought you must’ve sold it to that fellow.” “Oh, it’s out in the back, Jim!” came the reply. “I had to put it there. This whole thing has been so nerve-wracking! I just couldn’t take the chance that someone else would come in and want to buy the set for even more! Now, give me your English friend’s phone number and we’ll get this sorted! After which,” he added with obvious distaste, “I’ll have to call that guy in Dublin and tell him the set has sold!” As it turned out, Clive phoned Des first, hearing the following words when the honest merchant picked up the phone: “I’m so glad you have rung, sir! Your books have nearly been the death of me! I may die of starvation because of them!”

Ten days later, a blue-bound, 38-volume version of The Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin carefully packaged from Galway arrived in Cambridge. A perfect Ruskin ending to a Ruskin story.

Epilogue

It is 1999; I am in New Orleans at a sociology conference. As per usual, in my spare time, I am on the lookout for antiquarian book shops. “Any Ruskin?” I ask in store after store in that city’s famed French Quarter. “No,” always the answer. Finally, there is one store left according to the list I have earlier copied out of the phone book in my hotel room (no Google in those days!). It is far down Decatur Street. It is, I see when I get there, a very old shop, with a very old man in charge. My usual question posed: “No, never get any Ruskin here. Haven’t for years. No one reads him now.” Pause. Then: “But wait a moment, I think I do have one Ruskin book. Check back in English Literature.” And there, incredibly, it is! A single volume of the Library Edition: Volume 35: Praeterita! How is this possible? It’s a maroon-binding, like mine. It won’t match Clive’s set, but it will complete his collection! And by facilitating this completion, at last, my “debt” to Clive will finally be paid: My friend, who had so generously put me in the way of a set of the Library Edition which rightfully should have been his—would have been his under different financial circumstances!—will have his Cook and Wedderburn entire. I buy the book. I can’t remember how much I paid. The cost was immaterial. Home in my smaller, North American aversion of Geneva, I carefully pack the book and ship it airmail to England, never even thinking of calling Clive to alert him about the gift that is winging its way over the Pond to Norwich Street, Cambridge, delighting in imagining him opening the package on coming home one evening after teaching.

Two weeks later, a large package, sent from the UK, arrives in Geneva. Opening it, I am shocked to discover it’s the same Volume 35 I had sent Clive. A letter is inside the book. In it, Clive explains that he couldn’t be more grateful for my thoughtfulness and generosity, but goes on to add that, not long before, another strange and wonderful thing happened: his best friend, Michael Vince, completely by chance, discovered a Volume 35 at an antiquarian book sale and bought it. But then, after he found out that Clive was lacking that particular volume, he gave it to him, as a birthday present, Clive thinks. As for the now truly “extra” copy of Volume 35, Clive wanted me to have it back just in case I wanted to give it to someone else.

It is 2006. I am in Switzerland, traveling, as I often do in June after my teaching year has ended, on Ruskin’s “Old Road,” ferreting out the many places he wrote about so elegantly, many of which he had drawn so beautifully. One place I want very much to find this year is the house in Mornex, not far from the Swiss version of Geneva, where Ruskin lived in 1862 during the months when Munera Pulveris, his sequel essays to Unto This Last, were printing serially in Fraser’s Magazine, in London. (Before long, Fraser’s, like the Cornhill Magazine, had before it, would censor Ruskin’s new essays on political economy because of the incendiary effect they were having on his readers.) At last, after some hours trying to find the house using my remarkedly bad French, I am directed to it. There, I meet the house’s owner, Suzanne Varady. Over the next few years, more visits to Mornex ensue and Suzanne and I become fine friends. Better still, it happens that Suzanne becomes more than a little interested in Mr. Ruskin. To support that interest, I regularly send her articles and books about him. She is always pleased. And then, what must now seem to be the obvious outcome occurs. Some years prior, Clive had returned to me the copy of Volume 35 I had sent him. Having a copy of that volume in my Leys School Library Edition, and now knowing of Suzanne’s keen interest in Ruskin, it seemed to me that, if anyone should have that “extra” volume, it was her good self; for who can understand Ruskin rightly who has not read his autobiography, Praeterita? I post the book. Suzanne is very, very delighted when it arrives. “It is a treasure to me,” she says in her thank you letter. And, in this way, the final volume in this strange saga of two Library Editions, found its way at last to its proper home.

It strikes me, as I near the end of these sentences, that this story does not merely demonstrate the truth of what Ruskin contends are the always salutary effects that attend the decision to always be an entirely honest merchant, it illustrates the salutary effects that follow in the wake of kind and selfless behavior generally, other lessons Ruskin tries to teach us in Unto This Last (indeed, such moral teachings lie at the heart of all his writings). Such fine effects are on prominent display throughout the tale: in Clive’s generosity in giving me a chance to buy a Library Edition which, by rights, should have been his; in Dr. Moseley’s decision to give me a remarkably fair (professor possible!) price for the set; in Charlotte Hegyi’s choice, for friendship’s sake, to hand-cut the more than 17,000 uncut pages in my new Library Edition; in Michael Vince’s finding and gifting the missing Volume 35 to Clive; in Suzanne Varady’s willingness to share her Mornex house with myself and other Ruskin folk over the years; even in the cranky help accorded me by the lady at the British Airways counter and the customs agent in Newark; in, finally and most importantly, the decision to stand on the principle of how to conduct business nobly and honestly made by Des Kenny in Galway, even when such a stance meant losing needed capital for his shop. With the exception of the Dublin collector who tried to tempt Des into placing self above principle, everyone in this story was helped, served, or made happier or stronger in some manner, was able to feel, whatever the role they played, that they had acted honorably. Not bad “pay” at any time, in any place.

“Treat the servant [or customer, or acquaintance, or anyone…] kindly,” wrote Ruskin in the first essay of Unto This Last, “The Roots of Honor,” “with the idea of turning his gratitude to account, and you will get, as you deserve, no gratitude, nor any value for your kindness. But treat him kindly without any economical purpose, and all economical purposes will be answered.” “In true commerce,” he wrote a few pages later, “as in true preaching, or true fighting, it is necessary to admit the idea of occasional voluntary loss, that sixpences have to be lost, as well as lives, under a sense of duty, that the market may have its martyrdoms as well as the pulpit, and trade its heroisms as well as war.” “All of which sounds very strange,” he said in the essay’s final paragraph, “the only real strangeness in the matter being that it should so sound.” (Library Edition, 15.31, 39, 42, respectively).

Last modified 22 June 2020