Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

"William Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh, and 22, Pall-Mall, London."

o Joseph Conrad, a fledgling writer, as to its more established contributors, it was

simply Maga. However, to the majority of nineteenth-century

readers throughout the British Isles it was Blackwood's, one

of the principal periodical organs for new fiction, especially a certain species of short

fiction. It published in serial longer works as distinguished as George Eliot's Scenes of Clerical Life (1858), as well as her short story "The Lifted Veil" (July 1859).

o Joseph Conrad, a fledgling writer, as to its more established contributors, it was

simply Maga. However, to the majority of nineteenth-century

readers throughout the British Isles it was Blackwood's, one

of the principal periodical organs for new fiction, especially a certain species of short

fiction. It published in serial longer works as distinguished as George Eliot's Scenes of Clerical Life (1858), as well as her short story "The Lifted Veil" (July 1859).

Owing to the distinguished nature of its contributors and high calibre of the diverse material it published, poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge hailed it as "an unprecedented Phenomenon in the world of letters" (cited in Matheson, 100), a surprising assessment, considering how brutally the conservative journal initially attacked his work. As a publication featuring a diverse range of high-quality material, it provided a model for Fraser's Magazine, published in London from 1830 to 1882 and as solidly Tory in its sentiments as Blackwood's.

The magazines in this genre were of a different intellectual stature from their early nineteenth-century counterparts, and they dominated Scottish periodical publishing in the early Victorian period, attracting a readership that spanned not only Scotland but also England. They appealed to the professional reading market that was building up in Scotland and provided the educated sections of Scottish society with the kind of varied intellectual stimulus they sought. [Matheson, 100]

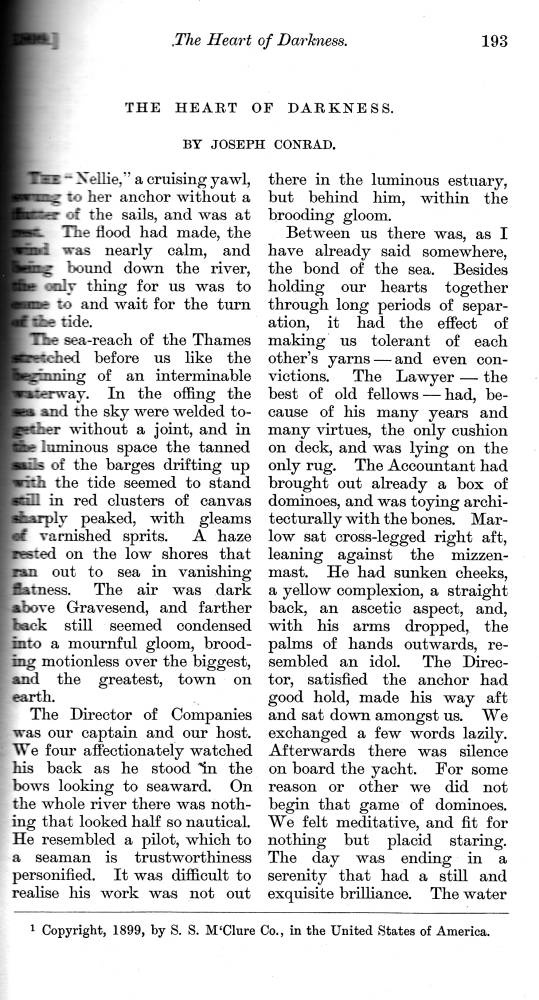

So devoted was novelist George Eliot to the magazine that she published all but one of her massive novels in it, the exception being Romola, which she serialised in the rival Cornhill, whose owner, George Smith, offered her a more exciting format, and arranged for her Renaissance novel to be illustrated by Sir Frederick Leighton. When she made her first submission, Scenes of Clerical Life (1858), William Blackwood did not know that the potential contributor was a woman. He took great interest in her work, and even went so far as publishing "The Lifted Veil" (July 1859) “anonymously, despite the success of Adam Bede, the 'better not to fritter away the prestige which should be kept fresh for the new novel [The Mill on the Floss]” (Small, ixl). Eliot's greatest work, Middlemarch, appeared serially in Blackwood's Magazine in eight monthly instalments (December 1871 through December 1872, skipping a month each time between instalments), although she had writted only three parts when the serial run began. Other notable literary contributors to Blackwood'sincluded Sir Edward G. D. Bulwer-Lytton, whose The Caxtons, A Family Picture ran serially April 1848 through October 1849), and Joseph Conrad, whose The Heart of Darkness ran in three parts (February, March, and April, 1899) and whose Lord Jim ran serially from October 1899 through November 1900) — unfortunately, all these significant novels first appeared without the benefit of illustration.

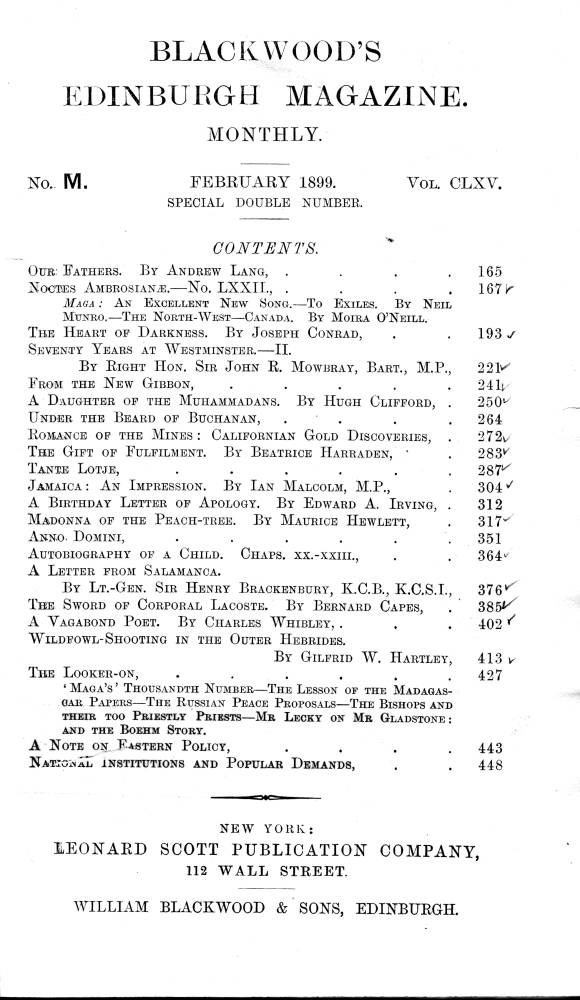

Left to right: (a) Title-page of volume 4, October 1818-March 1819. (b) Index, showing the anonymous "Night in the Catacombs". (c) Opening of "A Night in the Catacombs" (p. 19). [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

In April 1817, the monthly literary journal began life as Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, edited by James Cleghorn and Thomas Pringle; however, at the conclusion of 1905, when the magazine moved its headquarters entirely to London, it became simply Blackwood's Magazine. It survived in that form until 1980, although the magazine experienced a sharp decline in circulation with advent of such new format, illustrated monthly literary journals as the Cornhill Magazine in 1860, when it went from 10,000 per month to just 3,000, ending twenty highly prosperous years as a joint London-Edinburgh publication. But even in the heyday of the illustrated monthlies it proved to have longevity under William Blackwood's successors, Alexander and John, publishing the fiction of Trollope, Lever, Hardy, and Wilde. So devoted was novelist George Eliot to the magazine that she published all but one of her massive novels in it, the exception being Romola, which she serialised in the rival Cornhill, whose owner, George Smith, offered her a more exciting format, and arranged for her Renaissance novel to be illustrated by Sir Frederick Leighton. Popular novelist Margaret Oliphant, born near Edinburgh, was also a frequent contributor and devotee of William Blackwood's monthly publication.

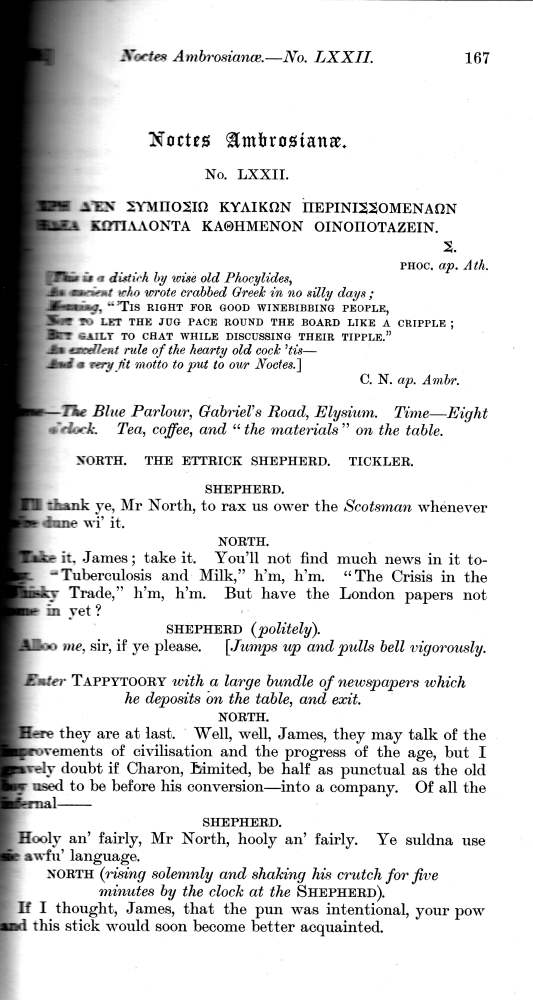

In its first number, publisher and former second-hand Edinburgh book-seller William Blackwood (1776-1834) signalled the reading public that he intended to publish extracts of memoirs, original verse, travelogues, antiquarian writings, reviews, synopses of parliamentary speeches, history (particularly Scottish history), and foreign affairs; it was a literary review rather than an organ for original fiction at the outset, a highly combative Tory or Conservative foil to the Whig Edinburgh Review, published from 1802 until 1929. Among the original contributors were Thomas De Quincey, John G. Lockhart (as editor), and James Hogg (whose nom de plume of "Ettrick Shepherd" accorded well with his tales of the supernatural involving the witches, elves, and fairies of the Scots peasantry — The Shepherd's Calendar published between April 1819 and April 1828, and admirably reprised in such tall tales as "The Mysterious Bride," of December 1830). Among its principal columnists were John Wilson (writing under the pseudonym "Christopher North") and (from 1819) William Maginn. Within four years of its inception, Blackwood's, with the advantage of far more frequent numbers than the unwieldy quarterly reviews then in vogue, began publishing original fiction with John Galt's Annals of The Parish serially in 1821, a classic example of such a tale being the anonymously published "Buried Alive" of October 1821.

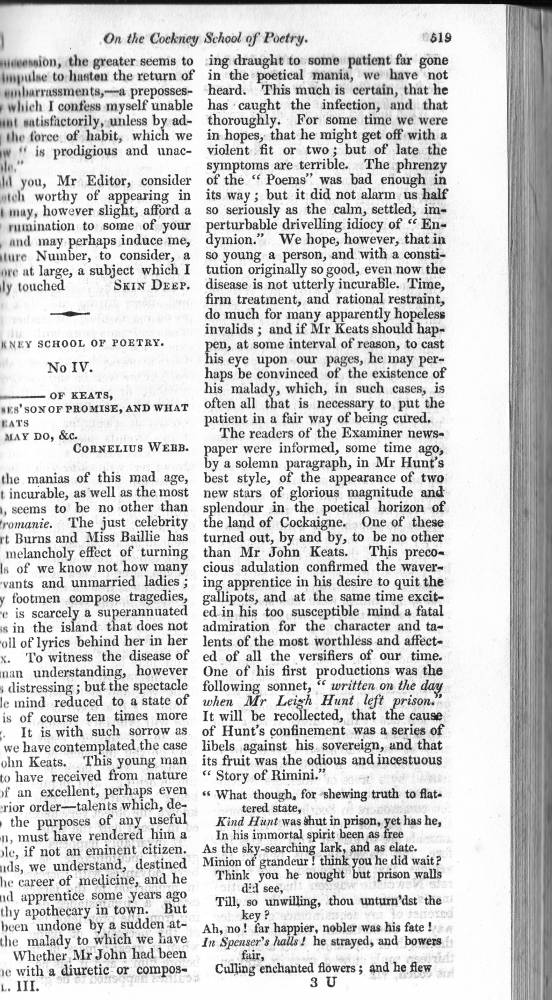

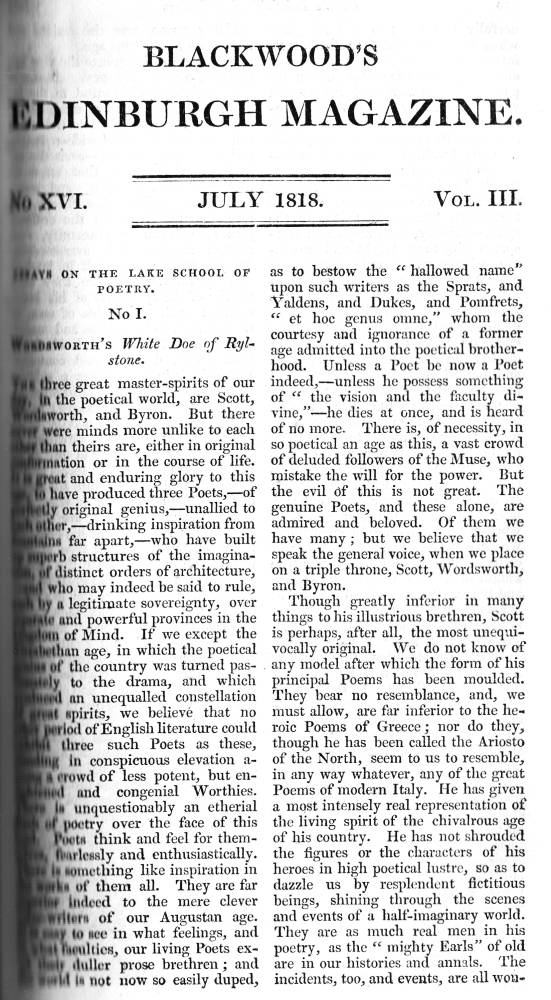

Left to right: (a) Attack on Leigh Hunt in "The Cockney School of Poetry, IV. 3 (1818): 519. (b) Lake School of Poetry and Wordsworth.

[Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Although J. G. Lockhart savagely (and on the basis of less than respectable social class as much as literary quality) derided John Keats's verse as belonging to "The Cockney School of Poetry," and John Wilson was as scathing in his attacks on Coleridge as was Lockhart on Leigh Hunt, Blackwood's published such radical early nineteenth-century English poets as Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Wordsworth, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The journal's other literary targets included the Romantic era essayists Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, and Leigh Hunt. Among the journal's most popular continuing features was a satirical column chiefly authored by John Wilson, supported by Thomas De Quincey and Maginn, "Noctes Ambrosianae," a kind of witty literary and political tabletalk for dedicated Blackwoodians which ran from March 1822 until February 1835 in seventy-one instalments.

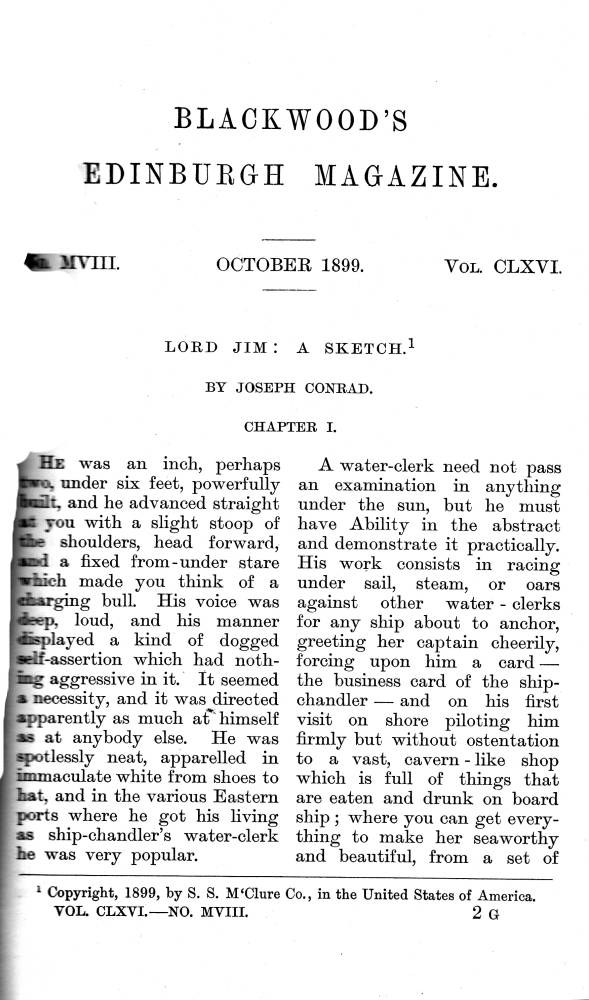

Left to right: (a) (b) Lord Jim: A Sketch (October 1899). (c) Noctes Ambrosianae (February 1899). (d) Opening of Heart of Darkness (February 1899) Index for February 1899 — issue 1000. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

By the end of the century, Blackwood's had become so venerable a literary institution that a novice writer such as Joseph Conrad could be justly proud of having one of his journeyman pieces, Heart of Darkness published in three monthly instalments in "Maga." Conrad, indeed, made his mark with the British reading public through this magazine, which published his early short fiction "Karain" (November 1897), "Youth" (September 1898), and "The End of the Tether" (July through December 1892). Other notable contributors over its 160-year history include John Buchan (whose The Thirty-Nine Steps appeared in the August-September 1915 numbers), Charles Neaves, Elizabeth Clementine Stedman, William Mudford, Charles Whibley, and Robert Macnish, who wrote under the nom de plume "The Modern Pythagorean." Margaret Oliphant describes in some detail the proceedings of the first eighty years of the house of Blackwood Annals of a Publishing House: William Blackwood and His Sons (3 vols., 1897). The magazine ceased publication in 1980. Particularly in its first decade of publication, the magazine did not always connect an author's name and the title of the story, so that Alan Lang Strout's A Bibliography of Articles in Blackwood's Magazine, 1817-1825 (1959) is useful tool for anybody researching stories and articles published during the magazine's early years.

Related Material

References

Cox, R. G. "The Reviews and the Magazines." The New Pelican Guide to English Literature. 6. From Dickens to Hardy. Ed. Boris Ford. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1958, rpt. 1983.

Harris, Wendell V. British Short Fiction in the Nineteenth Century: A Literary and Bibliographic Guide. Detroit: Wayne State U. P., 1979.

Harvey, Paul, ed. "Blackwood's Magazine." Oxford Companion to English Literature. Fourth Edition. Oxford and New York: Clarendon and Oxford U. P., 1983.

Hidden Treasure Tales from 'Blackwood'. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood, 1969.

Matheson, Ann. "Scottish Periodicals." Victorian Periodicals: A Guide to Research. Ed. J. Don Vann and Rosemary T. VanArsdel. New York: MLA, 1989. Vol. 2.

Morrison, Robert, and Chris Baldick, eds. Tales of Terror from Blackwood's Magazine. Oxford World's Classics. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Small, Helen, ed. "A Note on the Text." The Lifted Veil and Brother Jacob by George Eliot. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics, 1999.

Sutherland, John. The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford U. P., 1989.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 19 June 2013.