History of the monument, its destruction, and replacement

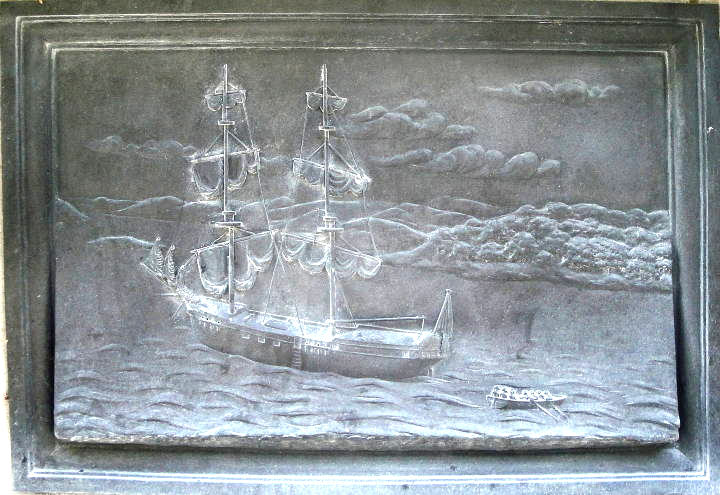

Memorial to Admiral Arthur Phillip by Charles Leonard Hartwell (modern copy” by W. Hamilton Buchan and Sharon A. M. Keenan). Original memorial 1932; most of the features of the present memorial date from 1968, 1976, and 2000. Bust originally bronze; bust now in resin coloured to resemble bronze; reliefs and descriptive panels beneath bronze; structure of monument, including main inscription panel, stone. Ward-Jackson explains, “Some parts of the memorial as it exists today are survivals from a large bronze wall monument in the style of the late eighteenth century, attached to the front of the church of St. Mildred Bread Street. This original memorial, which was blown down when a parachute mine destroyed the church on 17 April 1941, had been unveiled by Prince George, the future King George VI, on December 7, 1932.” Present location: Watling Street at the edge of a small garden in front of 25 Cannon Street, facing the front of New Change Buildings.

Vice-Admiral Arthur Phillip (1738-1814), first governor of New South Wales and founder of Sydney, Australia [from the DNB (1905)

Arthur Phillip was born in the parish of All-hallows, Bread Street, London, on 11 Oct. 1738, the son of a teacher of languages . . . His mother was Elizabeth (née Breach), the widow of Captain Herbert, R.N. The boy, being intended for the navy, was educated at Greenwich, and in 1755 became a midshipman in the Buckingham; this vessel was on the home station till April 1756, and then went as second flagship under Admiral” byng to the Mediterranean, where Philip first saw active service. He followed his captain, Everett, to the larger ship, Union, and then to the Stirling Castle, which went to the West Indies in 1761. He was at the siege of Havannah in 1762, and was there promoted lieutenant on 7 June 1762.

In 1763, when peace was declared, Phillip married and settled at Lyndhurst, where he passed his time in farming and the ordinary magisterial and social occupations of a country gentleman. But it would appear that about 1776 he offered his services to the government of Portugal, and did valuable work in that country. On the outbreak of hostilities between France and Great Britain in 1778, he returned to serve under his own flag. On 2 Sept. 1779 he obtained the command of the Basilisk fireship; on 80 Nov. 1781 he was promoted post-captain to the Ariadne, and on 23 Dec. transferred to the Europe of 64 guns. Throughout 1782 he was cruising, and in January 1783 was ordered to the East Indies, but arrived home in May 1784, without being in action.

In 1786 Phillip was assigned the duty of forming a convict settlement in Australia. . . . Phillip proved exceptionally well suited for the work. From September 1786 he was engaged in organising the expedition, and on 27 April 1787 he received his formal commission and instructions. The 'first fleet,' as it was so long called in Aus- tralia, consisted of the frigate Sirius, Captain (afterwards admiral) Hunter (1738-1821) , the tender Supply, three store-ships, and six transports with the convicts and their guard of marines. On 13 May 1787 it set sail, Phillip hoisting his flag on the Sirius. Dangers began early, for before they cleared the Channel the convicts on the Scarborough had formed a plan for seizing the ship. Making slow progress” by way of Teneriffe and Rio Janeiro, the fleet left the Cape of Good Hope, where the last supplies were taken in, on 12 Nov. On the 25th Phillip went on board the Supply, and pushed on to the new land, reaching Botany Bay on 18 Jan. 1788.

Phillip and HMS "Supply" reaches Australia.

Founding the penal colony.

It was of the first importance to make the colony self-supporting, and the soil around Sydney turned out disappointing. The unwillingness of the convicts to work became daily more apparent, and it would be long before free settlers could be induced to come over. In October 1788 Phillip despatched the Sirius to the Cape for help. The frigate returned in May 1789 with some small supplies; but even in January 1790 no tidings from England had yet reached the colony; the whole settlement was on half-rations; the troops were on the verge of mutiny, and their commanding officer was almost openly disloyal. Phillip shared in all the privations himself; kept a cheerful countenance, encouraged exploration, and made every effort to conciliate the natives. It was not till 19 Sept. 1790 that the danger of starvation was finally removed. About the same time Phillip's efforts to enter into regular relations with the natives bore fruit. On a visit to the chief, Bennilong, he was attacked and wounded” by a spear; but he would allow no retaliation, and his courage produced a good effect. Bennilong sent apologies.” by the firmness with which he dispensed justice to native and to convict alike, Phillip gradually won the confidence of the former, and when he left the colony in 1792 the native chiefs Bennilong and Yemmerawanme asked to accompany him to England. To exploration Phillip had little time to devote. As early as March 1788 he examined Broken Bay at the mouth of the Hawkesbury River, calling the southern branch Pitt Biver, after the prime minister. In April 1788 he made an inland excursion, but did not get far. In July 1789 he explored the Hawkesbury River to Broken Hill. In April 1791 he set out with a party to explore the Nepean River, taking natives with him, and, not being successful, he sent another party in June 1791, which produced better results. The settlement of Norfolk Island was entirely due to Phillip and his lieutenant, King. In September 1791 his confidential envoy, King, arrived from England, and brought from the home government formal approval of his policy. But Phillip's health was failing, and in November he asked permission to resign.

His government was still full of difficulties. In December the convicts made a disturbance before Government house” by way of protest against Phillip's regulations for the issue of provisions; Phillip repressed such disorder with a strong hand. The home government begged him to withdraw his resignation. But his state of health compelled him to return to England on 11 Dec. 1792, and final permission to resign was granted him on 23 July 1793.

Phillip's energy and self-reliance, his humanity and firmness, made a lasting impression on New South Wales. He per- manently inspired the colony, despite the unpromising materials out of which it was formed, with an habitual respect for law, a deference to constituted authority, and an orderly behaviour (Rusden).

On his return to England Phillip's health improved, but he lived in retirement on the pension granted 'in consideration of his meritorious services.' On 1 Jan. 1801 he became rear-admiral of the blue, on 23 April 1804 rear-admiral of the white, and on 19 Nov. 1805 of the red. On 25 Oct. 1809 he was made vice-admiral of the white, and 1 on 31 July 1810 of the red. He died during November 1814 at Bath. — C. A. H. [C. Alexander Harris], Dictionary of National Biography, 1st edition

[Click on these images for larger pictures.] Photographs by Robert Freidus. You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography [from the DNB]

Gentleman's Magazine. 1814, ii. 507.

Naval Chronicle, xxvii. 1

Phillips, Arthur. Voyage to Botany Bay. London, 1789.

Rusden, George William. History of Australia. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1883.

Therry, History of New South Wales.

Last modified 12 July 2011