Translated and adapted for the

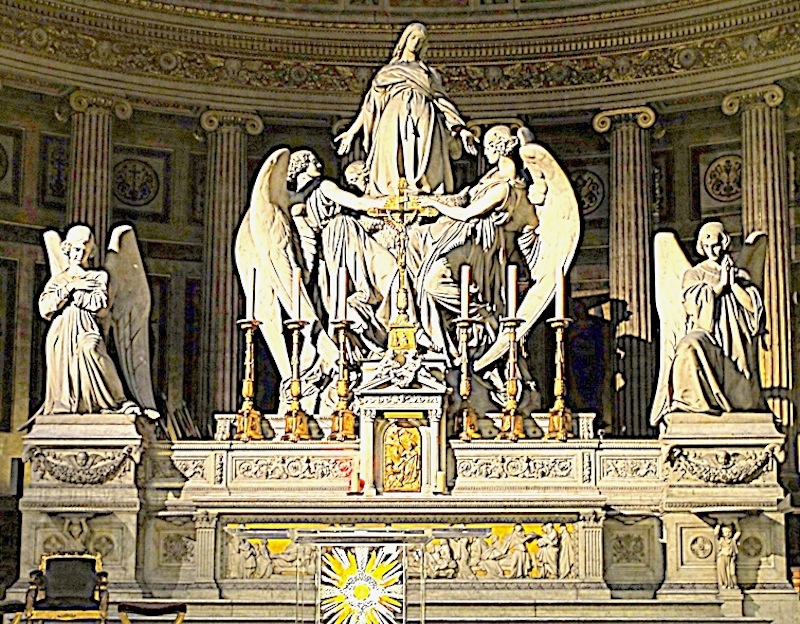

The Assumption of St Mary Magdalene, in marble, in the Church of the Madeleine in Paris, by Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867). [Note that the high altar's antependium, or fixed marble front, is now fully visible, as it was not in the past — see an earlier photograph of the same altar.]

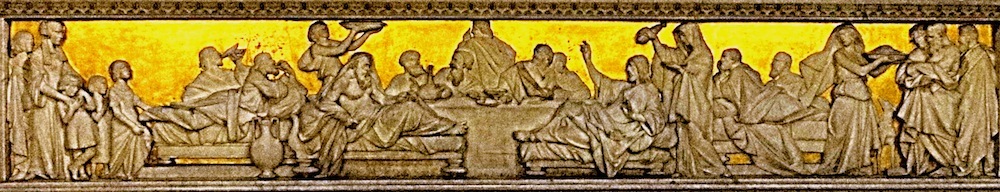

Paule Bathiard's new altar in the Church of the Madeleine in Paris was blessed on 16 December 2012, during the 11 p.m. mass. With its slim lines and light structure, it now gives us a clear view of the high altar of white marble behind it. This reveals Carlo Marochetti's bas-relief decorating its antependium, which was previously obscured. The bas-relief depicts the New Testament Bible story of The Meal at Simon's House.

The Antependium Bas-Relief

The bas-relief on the antependium, of white marble against a background of gold leaf, showing The Meal at Simon's House [also called "The Anointing at Bethany"]. Executed 1842-43.

The bas-relief of The Meal at Simon's House (detail) [showing Mary Magdalene anointing Jesus's head with precious ointment]

The episode is told by all four evangelists, with some variations. Marochetti has illustrated the version found in Matthew 26, 6-13, and Mark 14, 3-19, which features an unidentified woman, rather than the versions in Luke, which identifies her as a repentant sinner, or John, which identifies her as Mary, sister of Martha and Lazarus — although all the women became associated with Mary Magdalene in the early Catholic tradition. In Matthew 26, the episode starts: "Now when Jesus was in Bethany, in the house of Simon the leper, there came unto him a woman having an alabaster box of very precious ointment, and poured it on his head, as he sat at meat" (26, 6-7). The central group of the bas-relief had to be restored after fire damage on the night of January 5/6 1875, and it was several years before the task was accomplished [see "Mobilier et Vitraux" ("Furniture and Stained Glass")]. But it clearly shows the disciples' indignation at what they consider to be the woman's wastefulness. Jesus gestures to them with his left hand, indicating that they should not be annoyed: "Let her alone; why trouble ye her?" (Mark 14,6), he says, raising his other hand to add, "She hath done what she could: she is come aforehand to anoint my body to the burying" (Mark, 14, 8). This also reveals the deeper significance of the anointment: "Verily I say unto you, Wheresoever this gospel shall be preached throughout the whole world, this also that she has done shall be spoken of for a memorial of her (Mark 14, 9).

It should be stressed that Marochetti had not been specifically commissioned to execute the bas-relief. In fact, in his directions of 30 June 1834, the Minister of the Interior had been vague about the other marble sculpture-work of the altar, stating simply that the sculptor should consult with the architect (see National Archives F/21/577). Yet a drawing by architect Jean-Jacques-Marie Huvé (1783-1852), dated June 1842 and preserved in the Médiathèque de l'architecture et du patrimoine [the Mediatheque of Architecture and Heritage], suggests that he was unfamiliar with the subject that Marochetti had chosen: instead of the "Meal at Simon's House," he depicted the Last Supper (Projet de maître-autel: Elévation).

Thus it was Marochetti's own choice to illustrate this episode from Mary Magdalene's life. As François Pupil points out, the scene is that of a banquet in ancient times, with Christ reclining, facing Simon, while Mary anoints him; Judas rises to mark his disapproval; the servants are busy around them, and around those of the apostles who are in attendance. Thus, Christ and Simon, on couches facing each other, are at the centre of the bas-relief, in the foreground. Mary, solemn and composed, with the fabric and drape of her robe shown in minute detail, stands behind Jesus, her left foot slightly out of the frame of the bas-relief, giving the scene the appearance of a tableau vivant. In adopting the triclinium — the formal dining room arrangement of a banquet of ancient times, Marcochetti was reusing Nicholas Poussin's idea for Penitence (1647), in the second series of the Seven Sacraments [...], a connection helpfully noted by Philip Ward-Jackson. Two centuries later this was no longer anything new, as it had been for Poussin (see Poussin's letters of 30 May 1644 and 2 February 1646). But, for Marochetti, such an arrangement had the advantage of producing a perfect fit for the low horizontal space in front of the altar for which his bas-relief was destined. The arrangement also allowed him to place the main protagonists of the scene, Christ and Simon, in the foreground, on couches facing each other. Marochetti's Christ would seem to refer to Poussin's tableau: the same posture, the same gesture with his right hand, with only that of his left arm being different.

The Family Group on the Left

Left to right: (a) The bas-relief of The Meal at Simon's House (detail) [showing the family group to the left of the antependium]. (b) Marochetti's Medallion portrait of Camille Marochetti in marble. (c) Marochetti's Medallion portrait of Maurizio and Filiberto Marochetti in bronze.

To the left of the scene, however, is a group that resists analysis, even by the insightful Hélène Zanin (see Zanin II: 144): that of a woman preceded” by her three children, a girl and two little boys, one with his hands clasped in prayer, the other tenderly held close to his mother and protected by her arms. The singularity of the presence of these spectators did not escape Antoine Kriéger, who, in 1937, concluded his description of the bas-relief by pointing out that servants come and go on each side, adding that some figures, outsiders at the banquet, are nevertheless present at the scene (330-31) — repeating almost verbatim the words of Anatole Gruyer in the General inventory of art treasures of France, who says that on each side, the servants come and go, while some figures, outsiders at the Lord's Supper, nevertheless attend this divine spectacle. The difference here is that the inventory takes Marochetti's bas-relief as a representation of the Last Supper, an understandable enough confusion in the case of a bas-relief on an altar.

Careful observation of this group supports the hypothesis that here is a "signature" of the artist: the representation of a true family portrait at the heart of this biblical scene. Giovanna / Jeanne, born April 10, 1836, Maurizio / Maurice, born August 31, 1837 and Filiberto / Philibert born November 28, 1838, shortly after the inauguration of Marochetti's equestrian statue of Emanuele Filiberto in the Piazza San Carlo, Turin (4 November 1838) and named thus for this reason — the three Marochetti children stand in front of their mother, Camille, who was born in 1816. The dresses and hairstyles of the mother and daughter, in contrast with those of the other female figures in the bas-relief, evoke the era during which the work was sculpted, but the sculptor has left their feet bare, as a sign of humility, and this ensures that nothing jars; the boys' tunics also harmonise with the clothes worn” by other figures, which belong to a” bygone age.

Camille's hairstyle, divided in two by a centre parting and falling in two bands on either side of her face, corresponds to that of a contemporary illustration [...] Three portraits of the sculptor's wife, made around the same time, also provide valuable evidence, the first executed by the sculptor himself [see above centre]. Jeanne / Giovanna's hair, smooth at the front and back, is then braided loosely in a plait caught up below the nape. [In a contemporary journal] one might believe that was one was reading a description of Camille and her daughter's hairstyles. If the portrait of Giovanna that remains in the family is that of a girl of a different age, and cannot provide evidence here, that of Maurizio and Filberto, on the other hand (above right), can be compared with the bas-relief in that it presents two young boys who could be taken as twins. One can find the resemblance to the little boys in the bas-relief in this 1849 portrait, but in the Madeleine frieze it is easy to see that that the child pressed against his mother, with his more childish face, is the younger one.

The Group on the Right

Left: The bas-relief of The Meal at Simon's House (detail) [showing the group to the right of the antependium]. Right: Croquis de l’atelier de Mr de Marocquetti (sic) au château de Vaux [Sketch of M. Marochetti's Studio at the Chateau de Vaux] (detail), by Louis Laurent-Atthalin (1818-1893), June 1843, in pencil and watercolour, enhanced with white chalk and ink. [Note the greyhound in the right foreground.]

In the upper right corner of the frieze, at the back, is a male figure. Wearing voluminous robes like the other male figures in the bas-relief, he has medium-length hair and his presence seems to balance the group. Did Marochetti want to depict the father of the family he had portrayed, without wishing to make himself too obvious? Such is the feeling evoked by the group. The touch would only be noticed” by those close to him — a way, surely, of placing his family under divine protection, by involving them all in this episode. Another thought here — representations of donors were not unusual in sacred art from the Middle Ages onwards. Since Marochetti was not fulfilling a definite commission, the bas-relief could therefore be considered a gift from the sculptor. This would help us to appreciate better the way he uses Poussin here: with his right arm raised, Christ seems to bless the family which is seen in the distance, rather than Mary Magdalene, whom the sculptor places behind him. It would explain why Marochetti illustrated "The Anointing at Bethany" as narrated by Matthew and Mark. Presenting himself as the donor, he, in effect, signs his masterpiece, "The Assumption of Mary Magdalene."

However, this family portrait would not be complete without the presence of a dog, which we see raising its head towards the plate of food being carried” by the maid at the right. It is a greyhound, recognisable” by its long muzzle. This relates well to Carlo Marochetti's dog, depicted in the foreground of the sketch of his studio (above right). The presence of the dog on the lookout for scraps injects a note of humour into the scene represented here, and recalls another passage from the Gospel: "yet the dogs eat of the crumbs which fall from their masters' table" (Matthew 15, 27). Similarly, representing his children close to Christ, Marochetti illustrates the words of Jesus: "Suffer the little children to come unto me,... for of such is the kingdom of God" (Mark 10, 14).

The eyes of the group at the extreme left of the bas-relief, the Marochetti family, are fixed on on Jesus and Mary Magdalene. These spectators are aware of the gravity of the scene they attend, in contrast to the group opposite, which seems more concerned with the dog's presence than the mystery of the anointing that is being played out before them. The maid, however, quickly turns her head toward Mary Magdalene, her swift reaction dislodging the veil that covers her head. As for the dog, it hopes to get some tasty morsel out of the incident!

For the inauguration of the Church of the Madeleine on 24 July 1842, the altar was erected in the choir (see La Presse and the Journal des débats of 24 July 1842), while the group that crowns it, showing the Assumption of Saint Mary Magdalene, was installed and blessed a year later (see La Presse, 16 and 24 July 1843). We can date the completion of the bas-relief to the end of spring 1842. Marochetti's eldest child was then six years old, her brothers five and four years in the following summer and autumn. Camille, their mother, was twenty-six.

If the work failed to attract the attention of critics, who were busy saving their comments for the main group adorning the altar, it nevertheless caught that of Astyanax Scaevola Bosio (1793-1896), nephew of François-Joseph Bosio. The younger Bosio, like Marochetti, had been a pupil of his uncle. Responsible for the statue of St. Adelaide in the Church of the Madeleine, he could not remain indifferent to the work of Carlo Marochetti. Commenting on Bosio's work on the high altar of the Church of Saint Vincent de Paul in Paris, the Journal des Artistes of 20 October 1844, more than two years after the inauguration of the Madeleine, says that "Bosio neveu [Bosio the nephew] has now completed the bas-relief on the subject of the Last Supper, measuring nine feet” by three feet, and that this skilful piece happily overcame the problems of such a subject: instead of seating the apostles, as well as Christ, he placed them on couches around the table" (353). It seems clear that Bosio was familiar with the example of "The Meal at Simon's House” by Carlo Marochetti.

Bibliography

Archives Nationales, Paris.

Gruyer, Anatole. Paris, Monuments Religieux. Vol. I. Paris: Plon, 1876.

Journal des Artistes. 2nd series. Vol. I. Part ("livraison") 30.

Kriéger Antoine. La Madeleine. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1937.

"Mobilier et Vitreux" (No. 79). Direction des Affaires Culturelles de la Ville de Paris. — Conservation des Œuvres d'Art Religieuses et Civiles, Archives La Madeleine. (The author warmly thanks Agnes Plaire and Lionel Britten for their hospitality and for their help in connection with the history of the restoration of the bas-relief after fire damage.)

Poussin, Nicolas. Collection de Lettres de Nicolas Poussin. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1824.

Pupil, François. L’église de la Madeleine, Histoire d'Une Paroisse. Paris, 2000.

Zanin, Hélène. Les Commandes Publiques Françaises du Sculpteur Carol Marochetti (1805-1867), Mémoire de Master 2 Historie de l'Art, Université Paris-Ouest-Nanterre 2 (2011-2012): 144.

Last modified 16 May 2014