Photographs by the author unless otherwise specified [You may use these photographs without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

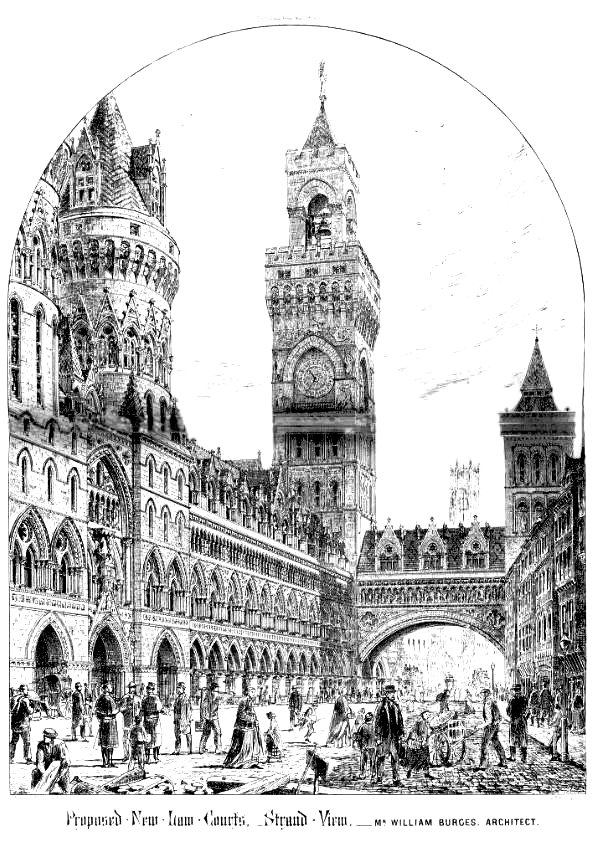

Town Hall (later City Hall), Bradford. Listed Building. Lockwood & Mawson, designed 1869, built 1870-73; substantially extended to the rear by Richard Norman Shaw as consultant to the City Architect, F. E. P. Edwards, 1905-09. Gaisby rock sandstone, with "[m]assive ashlar block ground floor and sandstone 'brick' with ashlar dressings to upper floors" (Listing Text). Centenary Square, Bradford — even more prominently sited than Lockwood & Mawson's Wool Exchange nearby. Neatly summed up as having a "[l]ong symmetrical façade with a tall slim central tower ... modelled on a Tuscan campanile" (Leach and Pevsner 153), very different in both respects from Leeds Town Hall with its quadrangular layout and heavy colonnaded tower. Both George Gilbert Scott's and William Burges's influences are very marked here, as the former's was on the Wool Exchange. This time perhaps the main influence was from Burges's failed entry for the competition for the Law Courts in London, especially in the juxtaposition of the long front range and the slender clock tower.

Left: Burges's entry for the Law Courts competition. Click on image for more information. Right: Shaw's large-gabled extension. © R. Lee, with many thanks. From the Geograph Project, and licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons licence. (Perspective corrected.)

Shaw, who designed the elevations for the six-storey almost triangular extension of the town hall to the rear, respected Lockwood's original style, expressly aiming to give "the appearance of one complete building under one roof" (Listing Text). But he injected some of his own characteristic notes as well, with balconies, dormers and large gables. The listing text finds Gothic, Romanesque Gothic and Queen Anne elements here, as well as rococo ironwork, describing all these rather lyrically as rising "one above the other, capped off by 2-storey gabled attics of French Gothic derivation." Particularly impressive is the great gable of the furthest end, along with the tall mullioned windows lighting the banqueting hall within. The flanking turrets add a more picturesque touch. Attractive as all this is, Lockwood's long façade and elegant clocktower make the more immediate impact.

Left to right: (a) The 220' high tower, topped by the figure of a dolphin pointing south-west. (b) The central gable, flanked by sculptures of Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria in canopied niches . (c) Closer view of Elizabeth (less weathered than Victoria).

The tower was inspired specifically by the campanile of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence ("City Hall"). It has a clock with four faces and 13 bells, together weighing 17 tons. The dolphin at the top looks tiny here, but is actually 9' long (all figures from "City Hall"). The central gable is one of three which relieve the long front range. This one projects into an elegant porch for the main entrance. The two queens by this beautifully carved entrance are part of a whole series of 7' high Kings and Queens of England (Oliver Cromwell is also represented), the rest standing in niches between the windows. The building is indeed "elevated in quality" by these impressive statues, all sculpted by Farmer and Brindley, each from a single stone from the local Cliffe Wood Quarry (Winfrey). Notice the fine scrolled ironwork of the gates and the impressive oriel window above the doorway.

The choice of early-mid 13c. Gothic style was undoubtedly influenced by Ruskin's lecture "Traffic," delivered at the earlier town hall building in April 1864, in which he decried the use of different architectural styles for religious and commercial purposes, feeling that such a separation indicated a divorce between religion and the actual business of life. See the discussion of Bradford Wool Exchange and Ruskin's "Traffic." But Peter Leach and Nikolaus Pevsner suggest another motive: "a desire for contrast with what had been done at Leeds" (60). The new grand town and city halls of this era surely did reflect "a new civic pride, competition among towns," and also, more generally, "the shift of power from the old landowning Tory aristocracy to the Nonconformist commercial classes" (Curl 287-88; but notice the reference here to religious faith as well).

As for the competitive element, the listing text too suggests that the town hall was intended "to compete with the Leeds and Halifax town halls." Thus, like other such buildings, it has richly appointed rooms for civic receptions, council meetings, court hearings and so on. In true High-Victorian manner, English and Latin texts are liberally distributed in the oak-panelled rooms of the Civic Suite here. In the Mayor's reception room (now the Lord Mayor's Room), for instance, there is a long sequence of texts taken from Virgil, Proverbs, Shakespeare etc. The Lord Mayor's Secretary's Room boasts such pithy mottoes as "By hammer and hand all arts do stand" and "Industry renders illustrious" ("City Hall").

Related Material

- Full text of "Traffic" — published version of Ruskin's talk in Bradford

- "Ruskin as Victorian Sage: The Example of 'Traffic'" — discussion by George P. Landow

- Charles Eastlake on Ruskin and the Gothic Revival (1872)

Sources

Bradford Town Hall, Bradford. British Listed Buildings. Web. 13 September 2011.

"City Hall: A Visitor's Guide." Leaflet available from reception.

Curl, James Stevens. Victorian Architecture. Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1990.

Leach, Peter, and Nikolaus Pevsner.Yorkshire West Riding: Leeds, Bradford and the North. The Buildings of England series. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2009.

Winfrey, Jane. "Bradford's Sculpture Trail." Bradford City Centre Management. Web. 13 September 2011.

Last modified 29 September 2012