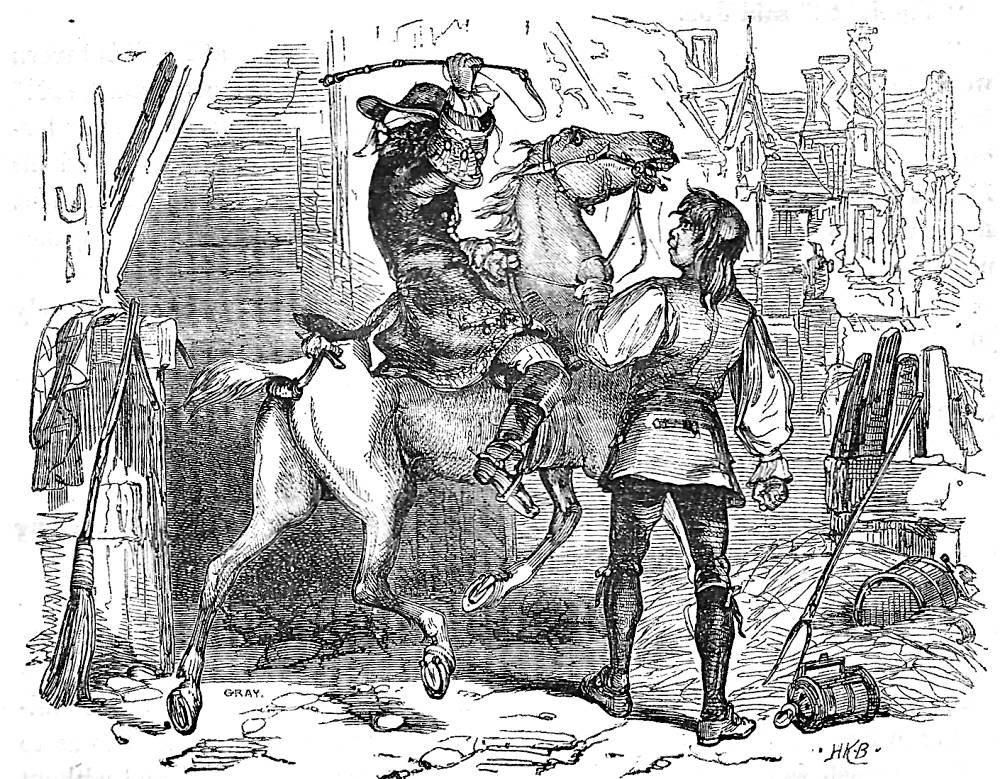

"Stand — let me see your face." by Fred Barnard. 1874. 5 ¼ x 6 ¾ inches (13.1 cm by 17.3 cm), framed. Gabriel Varden, the locksmith, confronts the "unsociable stranger" from The Maypole in Dickens's Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty, for Chapter II, 10. Headpiece for the first chapter, 1. [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them.]

Context of the Headpiece: Gabriel Varden encounters the Unsociable Stranger

"Did you never see a locksmith before, that you start as if you had come upon a ghost?" cried the old man in the chaise, "or is this," he added hastily, thrusting his hand into the tool basket and drawing out a hammer, "a scheme for robbing me? I know these roads, friend. When I travel them, I carry nothing but a few shillings, and not a crown’s worth of them. I tell you plainly, to save us both trouble, that there’s nothing to be got from me but a pretty stout arm considering my years, and this tool, which, mayhap from long acquaintance with, I can use pretty briskly. You shall not have it all your own way, I promise you, if you play at that game. With these words he stood upon the defensive.

"I am not what you take me for, Gabriel Varden," replied the other.

"Then what and who are you?’ returned the locksmith. ‘You know my name, it seems. Let me know yours."

"I have not gained the information from any confidence of yours, but from the inscription on your cart which tells it to all the town," replied the traveller.

"You have better eyes for that than you had for your horse, then," said Varden, descending nimbly from his chaise; "who are you? Let me see your face."

"While the locksmith alighted, the traveller had regained his saddle, from which he now confronted the old man, who, moving as the horse moved in chafing under the tightened rein, kept close beside him.

"Let me see your face, I say."

"Stand off!"

"No masquerading tricks," said the locksmith, "and tales at the club to-morrow, how Gabriel Varden was frightened by a surly voice and a dark night. Stand — let me see your face."

Finding that further resistance would only involve him in a personal struggle with an antagonist by no means to be despised, the traveller threw back his coat, and stooping down looked steadily at the locksmith.

Perhaps two men more powerfully contrasted, never opposed each other face to face. The ruddy features of the locksmith so set off and heightened the excessive paleness of the man on horseback, that he looked like a bloodless ghost, while the moisture, which hard riding had brought out upon his skin, hung there in dark and heavy drops, like dews of agony and death. The countenance of the old locksmith lighted up with the smile of one expecting to detect in this unpromising stranger some latent roguery of eye or lip, which should reveal a familiar person in that arch disguise, and spoil his jest. The face of the other, sullen and fierce, but shrinking too, was that of a man who stood at bay; while his firmly closed jaws, his puckered mouth, and more than all a certain stealthy motion of the hand within his breast, seemed to announce a desperate purpose very foreign to acting, or child’s play.

Thus they regarded each other for some time, in silence. [Chapter II, 10]

Commentary: "Stand — let me see your face."

The exciting incident to which Barnard alludes in his initial regular illustration occurs just after the meeting of The Maypole worthies in the opening chapter. Its presence as the headpiece underscores the importance of the "unsociable stranger" at The Maypole (eventually revealed as Barnaby's father, thought to have been murdered twenty-two years earlier) and the genial locksmith of Clerkenwell, Gabriel Varden, whom Dickens originally had considered making the story's protagonist. There is no precise parallel for this scene ion the original series, which instead has the old ruffian assaulting Joe Willet with his riding crop before he gallops away from the inn — and encounters Varden. Barnard effectively captures the tense atmosphere of the scene on the highroad near The Maypole in the rain and darkness of the gloomy night not far from where Varden has had a commission, at The Warren, the ancestral home of the Haredales. The meeting occurs near the village of Chigwell, twelve miles north of London, where the stranger will appearagain, playing the role of assailant in a street mugging, not far from the Rudges' hovel in Southwark.

Barnard like Phiz feels it is necessary to introduce the surly stranger as early as possible in a way that connects him with the plot secret behind the murders of Reuben Haredale and his steward twenty-two years earlier. However, Barnard does so in the context of a scene that the original illustrator had not attempted. In the sequence of the British Household Edition thus far, in fact, there is littleo overlap between the extensive 1841 program and that for the 1874 Household Edition volume, and fairly consistently throughout Barnard seems have avoided scenes provided by George Cattermole and Hablot Knight Brown.

Relevant Illustration from the 1841 First Edition

Above: Phiz's description of the other confrontational scene involving the threatening stranger and Joe Willet, A Rough Parting in Ch. II (20 February 1841).

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First illustrators: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (13 Feb.-27 Nov. 1841)

- Cattermole's Seventeen Illustrations (13 Feb.- 27 Nov. 1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's Six Illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s ten Diamond Edition Illustrations (1867)

- A. H. Buckland's six illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz and George Cattermole. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

Last modified 21 January 2020