Background Information

- George Cattermole, 1800-1868; A Brief Biography

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First Illustrators of Barnaby Rudge (13 February - 27 Nov. 1841)

- The Illustrations for The Old Curiosity Shop (25 April 1840 - 6 February 1841)

Seventeen Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (13 February-27 Nov. 1841)

- The Maypole, Part One, Chapter 1 (13 February 1841)

- Alternate version: The Maypole (1841)

- Mr. Tappertit's Jealousy, Part Three, Chapter 4 (27 February 1841)

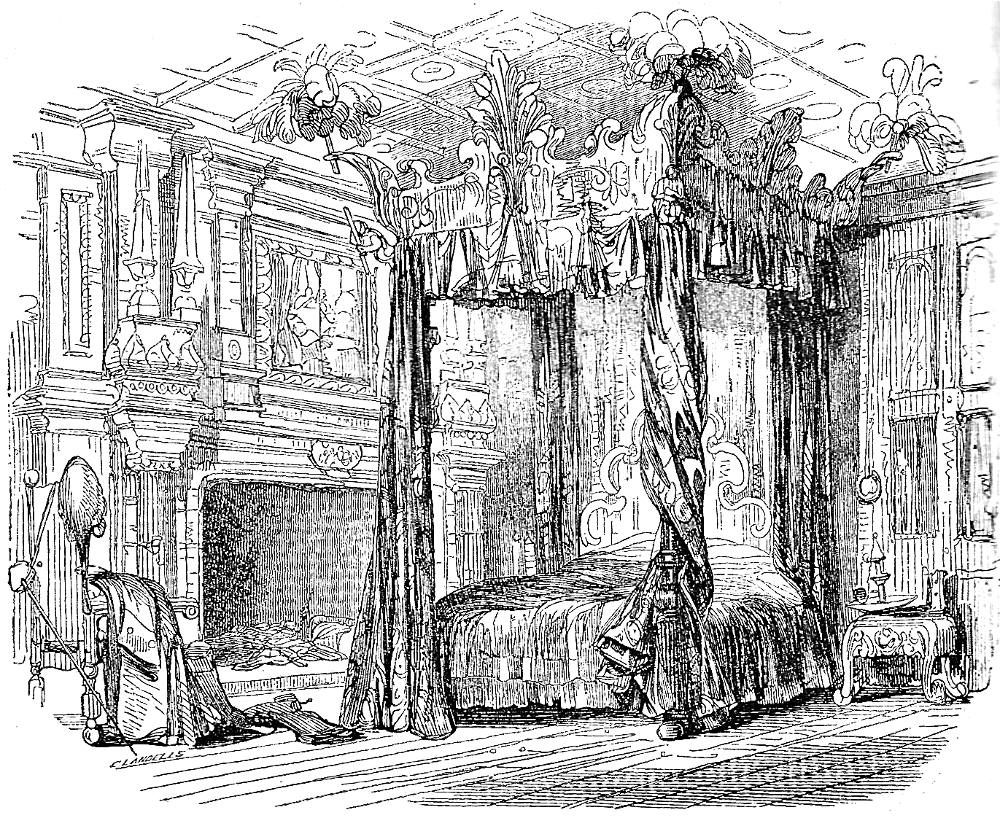

- The Best Apartment at The Maypole, Part Six, Chapter 10 (20 March 1841)

- The Warren, Part Eight, Chapter 13 (3 April 1841)

- The Watch Crying out the Hour, Part Nine Chapter 16 (10 April 1841)

- The Maypole's State Couch, Part Twelve, Chapter 22 (1 May 1841)

- Old John Asleep in his Cozy Bar, Part Fourteen, Chapter 25 (15 May 1841)

- Miss Haredale on the Bridge, Part Sixteen, Chapter 29 (29 May 1841)

- Mr. Haredale's Lonely Watch, Part Twenty-two, Chapter 42 (10 July 1841)

- A Chance Meeting in Westminster Hall, Part Twenty-three, Chapter 43 (17 July 1841)

- The Rioters' Head-Quarters, Part Twenty-seven, Chapter 52 (14 August 1841)

- A Raid on the Bar, Part Twenty-eight, Chapter 54 (21 August 1841)

- The Murderer Arrested, Part Twenty-nine, Chapter 56 (28 August 1841)

- The Ladies' Escort, Part Thirty-six, Chapter 69 (16 October 1841)

- Carrying Off the Prisoners, Part Thirty-six, Chapter 69 (16 October 1841)

- Lord George Gordon in The Tower, Part Thirty-eight, Chapter 73 (30 October 1841)

- Sir John Chester's End, Part Forty-two, Chapter 81 (27 November 1841)

Dickens switches from Cruikshank to Phiz and Cattermole

Originally, Dickens had had veteran illustrator George Cruikshank in mind as his sole illustrator for the historical novel when he proposed it to publisher Richard Bentley, However, when his editorial squabbles with Bentley came to a head, Dickens ceased work on the project, and Cruikshank took the commissions of a number of other authors, so that in January 1841 Dickens, taking up the novel again in earnest, suddenly found himself without Cruikshank. Thus, Dickens chose torevert to Phiz, his partner in The Pickwick Papers and Nicholas Nickleby. According to Browne Lester, Phiz produced fifty-nine illustrations for the roaring tale, "mainly of characters, Cattermole producing about nineteen, usually of settings" (85). Browne Lester describes Phiz's specialty at this point as the "low" characters such as Hugh and Sim Tappertit, "active moments, and comic rascality, while Cattermole would embark upon loftier, antiquarian, angelic, and architectural subjects" (78).

Cattermole versus Phiz in Weekly Part-publication

Twenty-five of forty-two weekly parts (date, number) in which no Cattermole illustrations appear: 20 February (2); 17 March (5); 27 March (7); 17 April (10); 24 April (11); 1 May (12); 8 May (13); 22 May (15); 5 June (17); 12 June (18); 17 June (19); 25 June (20); 3 July (21); 24 July (24); 31 July (25); 7 August (26); 4 September (30); 18 September-23 October (32-37); and 6-20 November (39-41). Although it is not architectural in nature, Dickens assigned the climatic confrontation in the Chigwell woods between the villainous Sir John Chester and the stoic Geoffrey Haredale to Cattermole, assuring his involvement in the project right up to the concluding number. J. A. Hammerrtton (1910) cites just fifteen plates as being by Cattermole, but in The Dickens Picture-Book he actually ascribes seventeen to him, and sixty-one by Phiz (initialed with "H. K. B.," rather than his nom de plume). Hammerton's Phiz figure includes both Master Humphrey's Clock frontispieces for the novel, but not the extra illustrations that he completed for the Cheap Edition (1849). With seventy-six wood-engravings dropped into the text, this, Dickens's fifth novel, ranks as his most highly illustrated, even without the extra five illustrations for 1849 Cheap Edition, and the additional two for the two-volume Library Edition (1858-59).

The Duo's Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (1841)

Dickens made the expensive decision to have the illustrations dropped into the text, rather than printed on separate pages, so that they would retain the closest possible relationship to his story. This meant that the illustrators had to create their designs for wood instead of steel because wood engravings can be inked and printed simultaneously with the raised typeface, whereas etching plates, with their ink in grooves rather than on the surface, must be sent through a rolling press and printed on individual dampened pages. [Browne Lester, 77-78]

Comparing the plates that appeared in the 1849 edition of Barnaby Rudge to those in a good modern edition, such as the volume in the New Oxford Illustrated Dickens, gives us an idea of how the Victorian reader might have experienced the plates by Phiz and Cattermole — that is, simultaneously with the letterpress illustrated rather than facing such text. In the first place, whereas the seventy-six plates in the New Oxford edition appear on a page 18.3 x 11.5 centimetres, those that Bradbury and Evans published in 1841 and 1849 appear on a larger page (25 by 16.5 centimetres). The paper on which the original wood-cuts were printed provides a more important difference than their slightly larger page: in the 1849 edition, the plates appear on the same paper as the text of the novel, and this arrangement permits printing text on the reverse of each illustration. In the New Oxford, the illustrations are free-standing rather than dropped into the text, usually facing the passages realised, and neither the initial-letter vignettes nor the frontispieces appear. In contrast, the original bound volume of 1841 (reprinted in 1849) has reproduced the plates on much heavier stock; in the 1841 and 1849 editions the text bleeds through slightly, but in the New Oxford it does not, thus making the plates look somewhat clearer. Moreover, the ornamental capital letter vignettes designed by Phiz to distinguish the monthly parts are not reproduced in modern editions, and pictures that served as head- and tailpieces appear on separate pages in the New Oxford. On the whole, the seventy-seven New Oxford Illustrated Dickens plates for Barnaby Rudge are quite clear, but those in the original often seem darker, sharper, and more dramatic, even though the plates are not printed on separate sheets but are integrated into the text, often with the print from the verso slightly showing through.

Eleven Initial-Letter Vignettes designed for the Monthly Parts

- Ornate capital "I," Ch. 1, p. 229: 13 February 1841

- Initial Letter "B," Ch. 6, p. 265: 6 March 1841

- Initial letter "I," Ch. 13, vol. 3, p. 1: 3 April 1841

- Initial letter "T," Ch. 23, p. 61: 8 May 1841

- Initial letter "O," Ch. 31, p. 109: 7 June 1841

- Initial letter "O," Ch. 33, p. 121: 12 June 1841

- Initial letter "T," Ch. 39, p. 157: 3 July 1841

- Initial letter "T," Ch. 49, p. 217: 7 August 1841

- Initial letter "B," Ch. 57, p. 265: 4 September 1841

- Initial letter "D," Ch. 65, p. 313: 2 October 1841

- Initial letter "A," Ch. 75, p. 373: 6 November 1841

Related Material Including Other Illustrations of the Novel

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (13 February-27 Nov. 1841)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First illustrators of Barnaby Rudge: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's Six Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge (1867)

- Household Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's 6 illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition of Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (1900)

- The Charles Dickens Library Edition Illustrations for Barnaby Rudge by Harry Furniss (1910).

Bibliography: Primary Sources

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz and George Cattermole. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury and Evans, 1849.

________. Barnaby Rudge. Ed. Kathleen Tillotson. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. The New Oxford Illustrated Dickens. London: Oxford University Press. 1954, rpt. 1987.

Bibliography: Secondary Sources

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "Part Three: Dickens and His Other Illustrators: George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio U. P., 1980. 125-34.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Edgecombe, Rodney Stenning. "Sources for the Characterization of Miss Miggs in Barnaby Rudge." Dickens Quarterly, 32, 2 (June 2015): 129-38.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cattermole." Charles Dickens and His Illustrators. London: 1899. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2004. 121-35.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 3. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock to Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 53-85.

Stevens, Joan. "'Woodcuts Dropped into the Text': The Illustrations in The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge." Studies in Bibliography. 20 (1967): 113-34.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York:: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 18 July 2015

Last modified 16 December 2020