The mode of publication — weekly instead of the usual monthly instalments — with "woodcuts dropped into the text," as well as collaboration with two artists (Williams and Maclise also contributed one cut apiece to The Old Curiosity Shop.), led Dickens to new use of illustrations for the two novels which constitute the bulk of his periodical, Master Humphrey's Clock. Not only Dickens have in his service George Cattermole's Gothic, architectural talents in addition to Browne's comic, sentimental, ones, but the illustrations — more numerous and placed precisely where the novelist wanted them in the text serve to sustain certain moods and tones more extensively could two etchings per monthly part. In some respects the ones for The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge are truly integral parts of the text than any of the other illustrated Dickens' novels. Joan Stevens has dealt extensively with the placement of the cuts at particular points in the text (see ibliography).

At the same time, because each cut illustrates a relatively larger portion of the text, each one usually can bear less freight thematic significance than the etchings for the monthly-part novels. The result is something closer to the modern comic strip to the Hogarthian moral progress, though those two also are related (see David Kunzle). Dickens could have Browne devote three cuts to the dents surrounding Dick Swiveller's illness and the Marchioness' heroism (in chapters 64, 65, and 66) (Textual references are to the first, three volume bound edition of Master Humphrey's Clock.), when one or at most etchings would have been provided according to the usual ratio; or, in Barnaby Rudge he could have his artists show, in [51/52] three successive cuts, Haredale arming at home (ch. 42, Cattermole), meeting Chester and Gashford in Westminster Hall (ch. 43, Cattermole), and then standing with his foot on the fallen Gashford, pointing accusingly at Chester (ch. 43, Browne). Indeed, sequences of up to nine (or, if the definition is broadened, eighteen) cuts can be identified, with the result that if one goes through the illustrations with brief quotations from the text (as in Hammerton's The Dickens Picture Book), the effect is virtually like reading a complete comic strip, with few details that are totally obscure to someone who has never read the novel.\

Some statistics will indicate how this sequential specificity is possible: The Old Curiosity Shop is about five-eighths the length of a novel like David Copperfield, while Barnaby Rudge is about three-fourths the length of such novels; but the Shop has seventy-five illustrations and Rudge seventy-six, compared with the usual forty. Thus proportionately there are two to three times as many illustrations in the weekly installments of Master Humphrey's Clock as in a monthly-parts novel.

Four of Thackeray's illustrations for Vanity

Fair and one of his symbolic decorated initial letters.

[Click on thumbnails

for the captions, texts illustrated, and commentary.] Not in print addition.

There is also a fundamental difference between what Dickens, Cattermole, and Browne achieve in the Clock novels and what Thackeray does with "woodcuts dropped into the text" in Vanity Fair and Pendennis. Thackeray's directly illustrative etchings and woodcuts are generally much less striking in effect than are his numerous initial letters and tailpieces, most of which are wittily emblematic as they provide symbolic commentary. In contrast, there are only twenty-five initial letters throughout the Clock, and few have any connection with the text; at the same time, the Clock's full-size cuts are, with a few important exceptions, devoid of emblematic details. Further, in contrast to Browne's developing practice in the monthly-part novels (where he increasingly emphasizes parallels between etchings), the relation of his and Cattermole's individual cuts in the Clock is largely sequential rather than thematic.

After the necessarily halting start, given the change in plans regarding The Old Curiosity Shop, which was originally intended as a short story, the illustrations settle down into a fairly consistent pattern: two cuts per number, usually full size but sometimes one a small tailpiece, and occasionally an initial letter at the opening of a number. Early in the work the narrative and [52/53] hence the graphic sequences are short, but by the fifteenth weekly number there is a six-cut sequence running through three numbers and five chapters; and from the second half of Number 19 through Number 23 a sequence of nine cuts, all by Browne, runs from chapter 24 through chapter 32. Considering that Browne was "never at home with the technique of wood cutting" because he could not envision "what changes an engraver might make in the appearance of his drawing" (E. Browne, p. 165.), the frantic pace involved in illustrating a weekly rather than a monthly publication, the effect of employing various engravers, and the other work Phiz had in hand at the time, the results are of surprisingly high quality, although the engravers did seem to have trouble with facial expressions. Phiz frequently seemed to treat the medium as if he expected the results to equal those obtained by etching, but the engravers often obliged by providing as subtle shading as can be produced by the method. In this respect the results are generally more successful than those achieved by his co-illustrator. Phiz was notably more skillful than Cattermole in dealing with human figures close up, and even his worst engraver, C. Gray, could not always drag him down to his level of crudity.

Although many of Browne's early cuts for The Old Curiosity Shop are somewhat caricatured, comic portrayals of characters, his Quilp is a notable creation. Less has been said in favor of his Nell, but compared to Cattermole's, who is either a wax doll or barely visible, Browne makes us believe in the "cherry-cheeked, red-lipped" child Quilp describes so lecherously, and yet the artist never loses the pathos of Nell's situation — indeed, it could be argued that Phiz's Nell is more flesh and blood than Dickens'. Phiz seems to have transcended the rigidity of figure which characterized his virtuous females in Nicholas Nickleby.

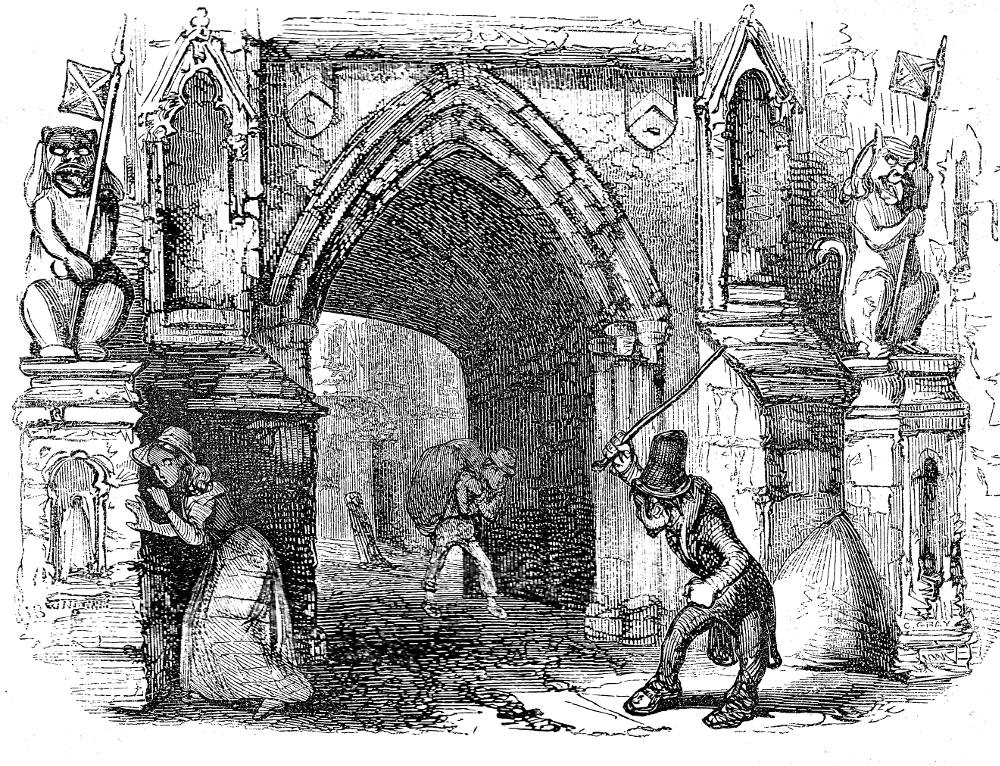

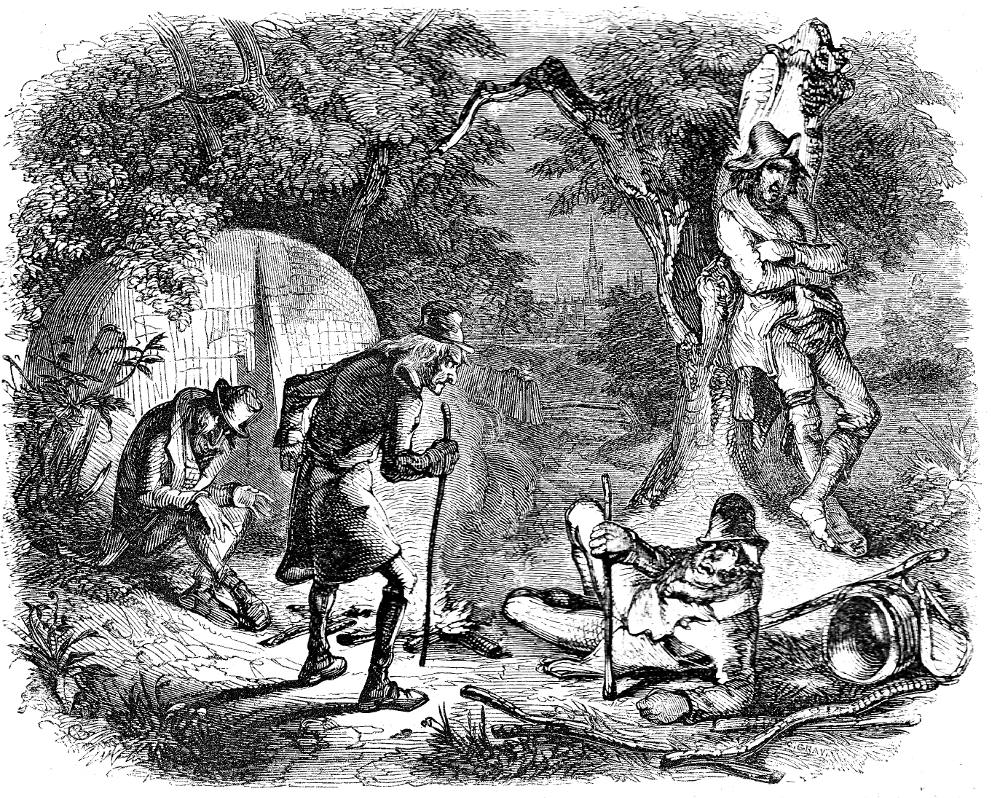

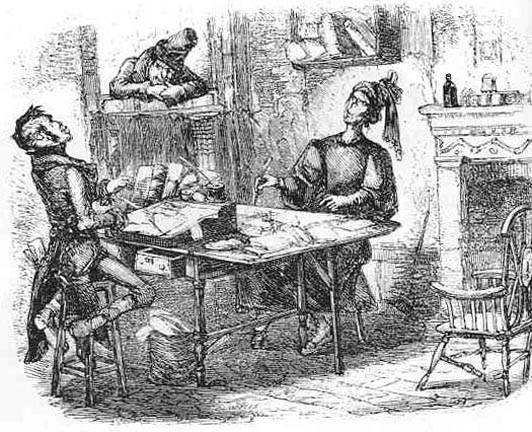

Nell hides from Quilp. Wood engraving, 3 1/8 x 4 ½ inches (8.4 x 10.6 cm). — Part Sixteen, Chapter 27, The Old Curiosity Shop: 22 August 1840.

The stylistic differences between the two illustrators are especially of interest because Browne traced all of George Cattennole's drawings for the earlier numbers — and some of the later ones as well — and transferred them to the woodblock (It has always been assumed that at some point fairly early, Cattermole took over the transferring of his own drawings; Yet among the tracings in the Gimbel Collection there are ones for Cattermole's designs for Barnaby Budge, all initialed "HKB," indicating that Browne continued to do at least some of this work for Cattermole nearly all the way through Master Humphrey's Clock.). The way Dickens seems to have seen the respective functions of his two illustrators, and the difficulty he had at times keeping to that conception, is typified in the evidence regarding an engraving of Nell cowering in fear that she will be seen by Quilp, who gestures to Tom Scott beneath an old arched gateway (ch. 27). As [53/54] wrote to Cattermole, the scene was put in "expressly with a view to your illustrious pencil. By a mistake, however, it went to Browne instead"(P, 2: 110.). Mrs. Leavis is probably correct in conjecturing that Browne achieved a better effect than Cattermole would have, especially in emphasizing Dickens' descrip tion of Quilp ("like some monstrous image that had come down from its niche") by suggesting a visual parallel between the gro tesque stone carvings and Quilp himself (Q. D. Leavis, p. 344). And the use of heavy, sinister looking architecture seems a precursor of Browne's later treatment of buildings in his dark plates. just how one should read the significance of the empty niches is more questionable, since Dickens' text specifically associates niches with monsters, rather than with the "guardian saints" Mrs. Leavis mentions.

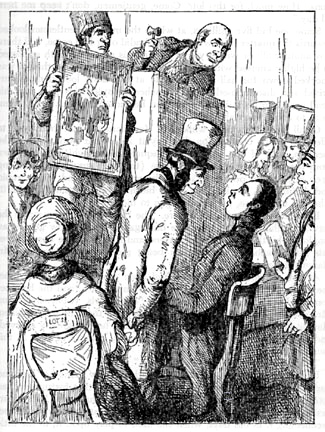

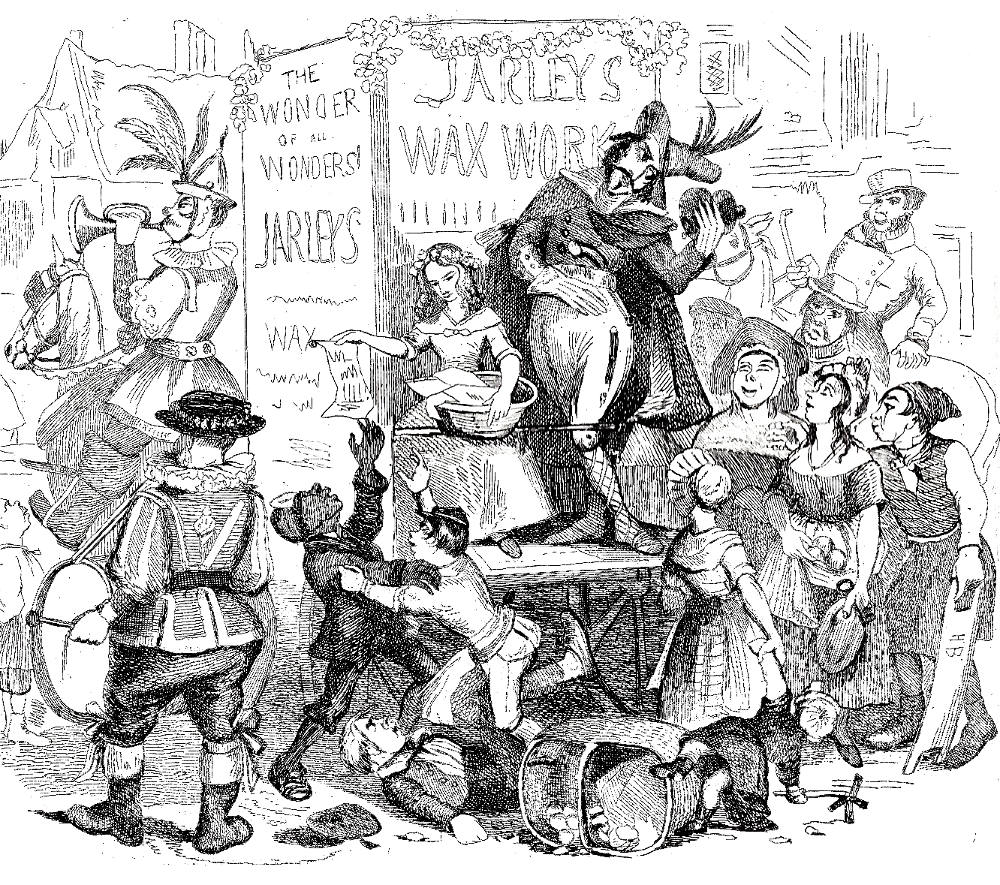

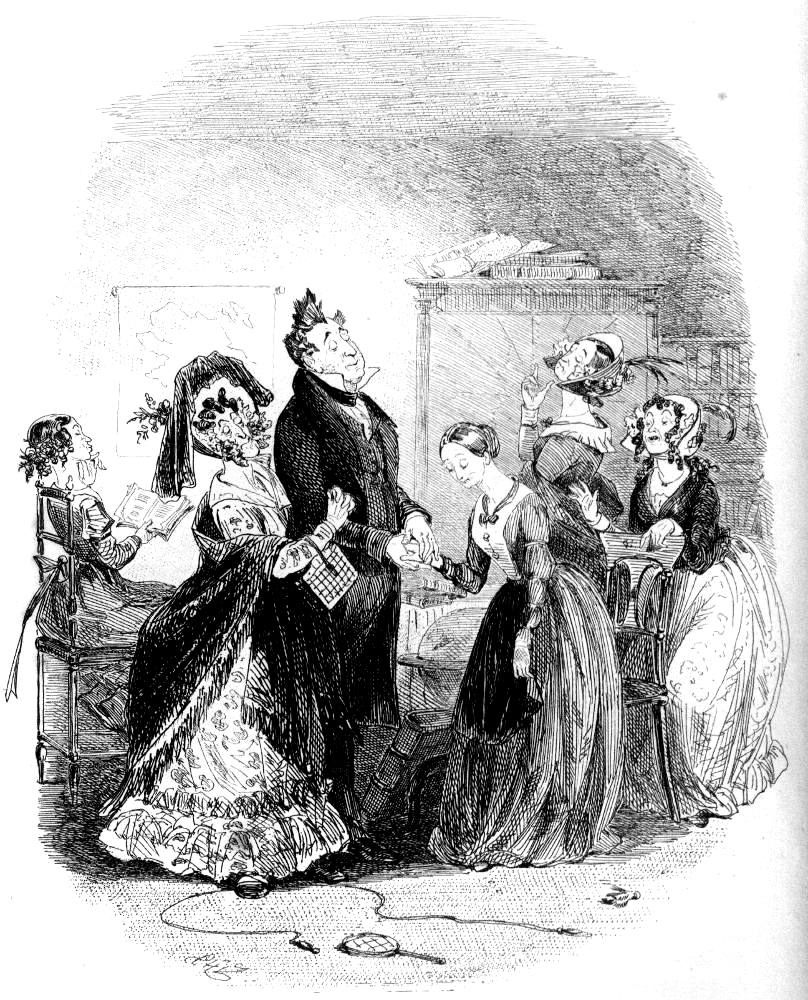

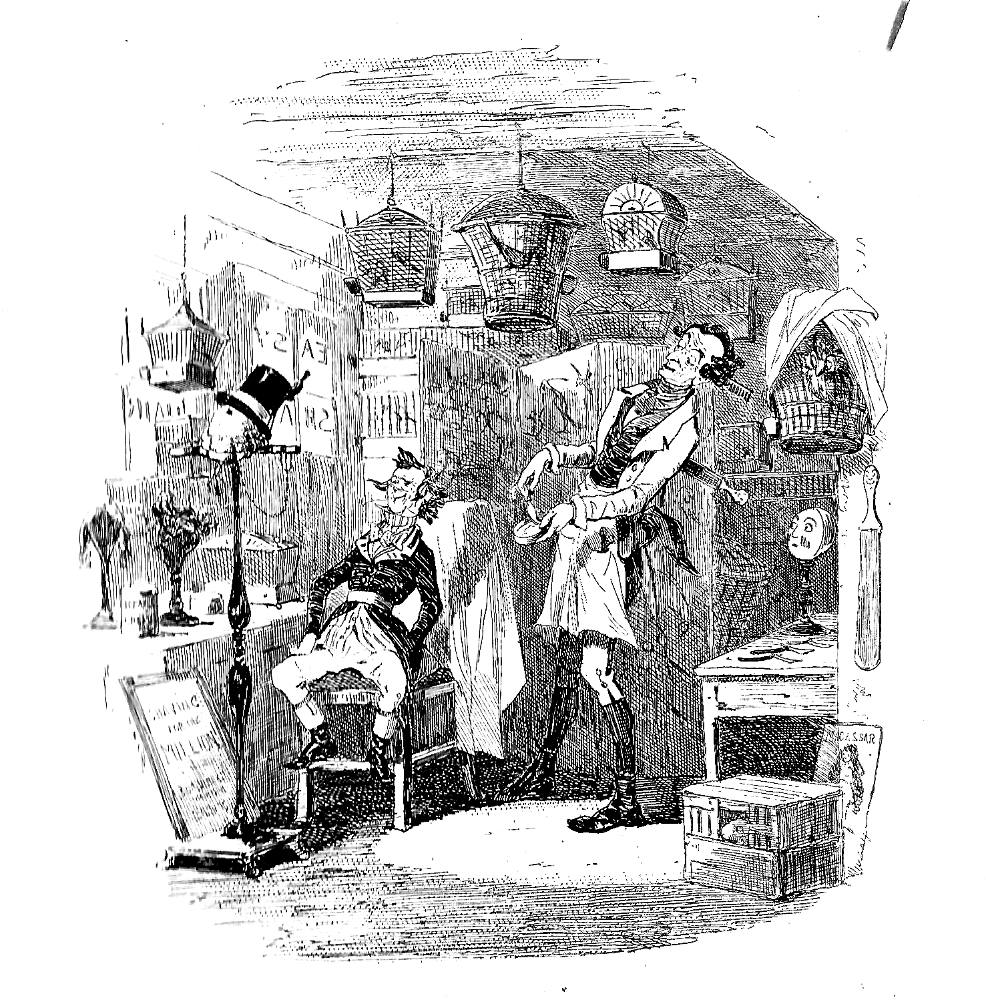

Producing a Sensation. Wood engraving, 3 ¾ x 4 ½ inches (9.6 x 11.4 cm). — Part Sixteen, Chapter 28, The Old Curiosity Shop: 22 August 1840.

Dickens' intention to give the subject to Cattermole implies a peculiar prejudice in favor of this artist and a mistaken preconception about what subjects Browne is most capable of handling; it may be symptomatic that in no surviving correspondence does Dickens praise Browne's work as effusively as Cattermole's. The novelist also intended Cattermole to do the first illustration for Number 22, that of Nell and the cart which travels around town advertising the waxwork (ch. 29); he had even enclosed a "scrap" of the manuscript for that subject in the letter referred to above. But for reasons unknown, Browne did that one too.

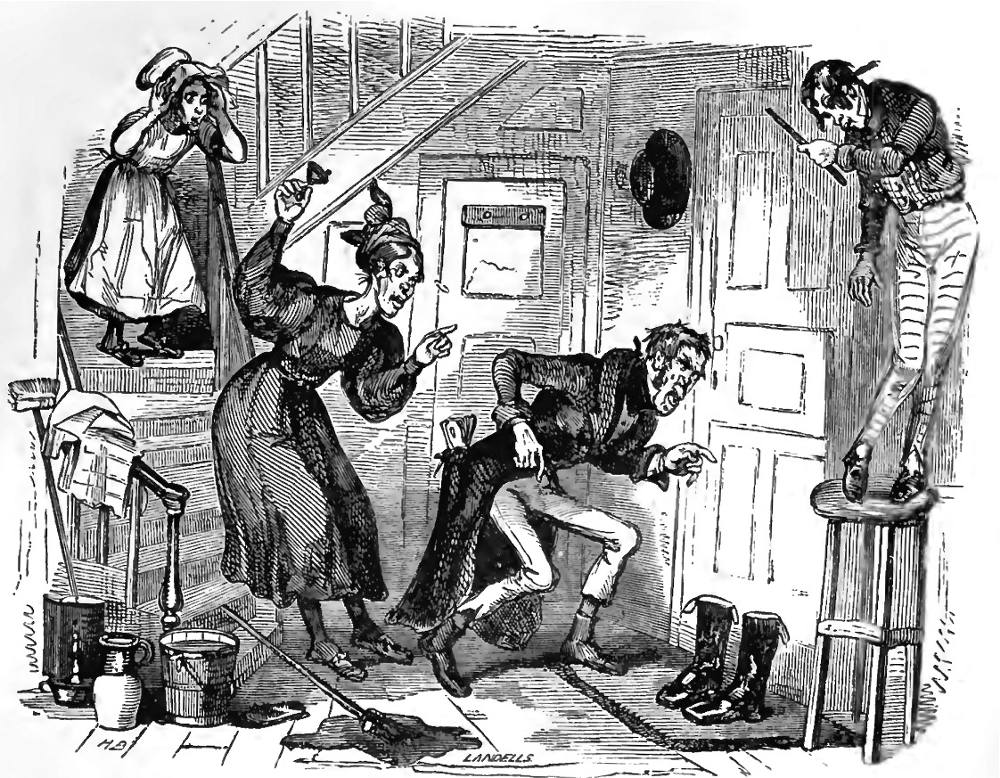

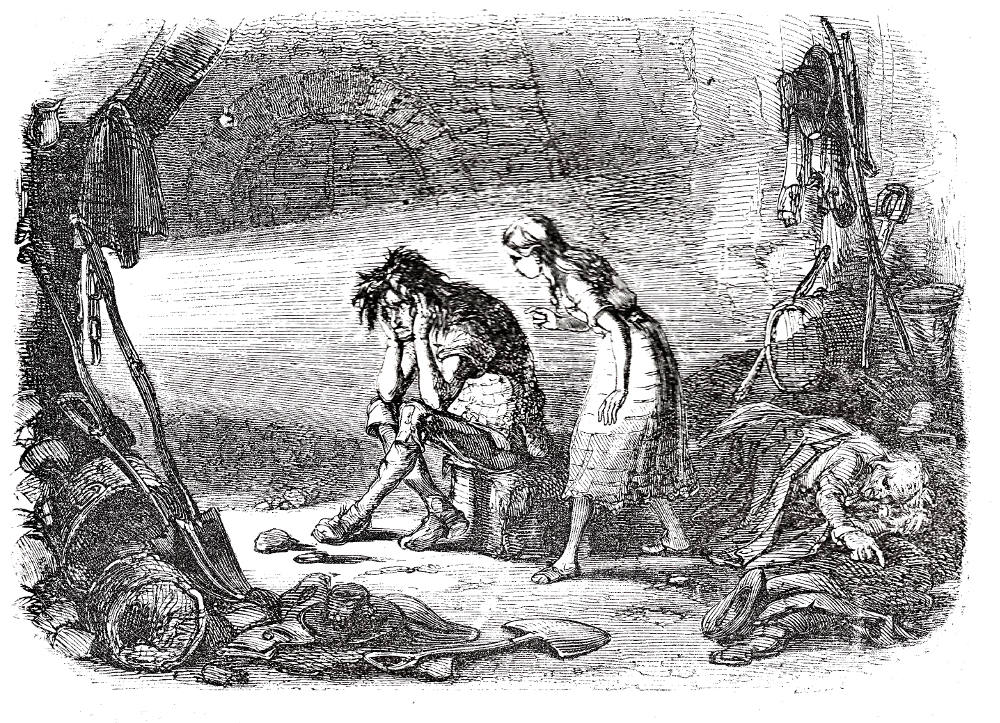

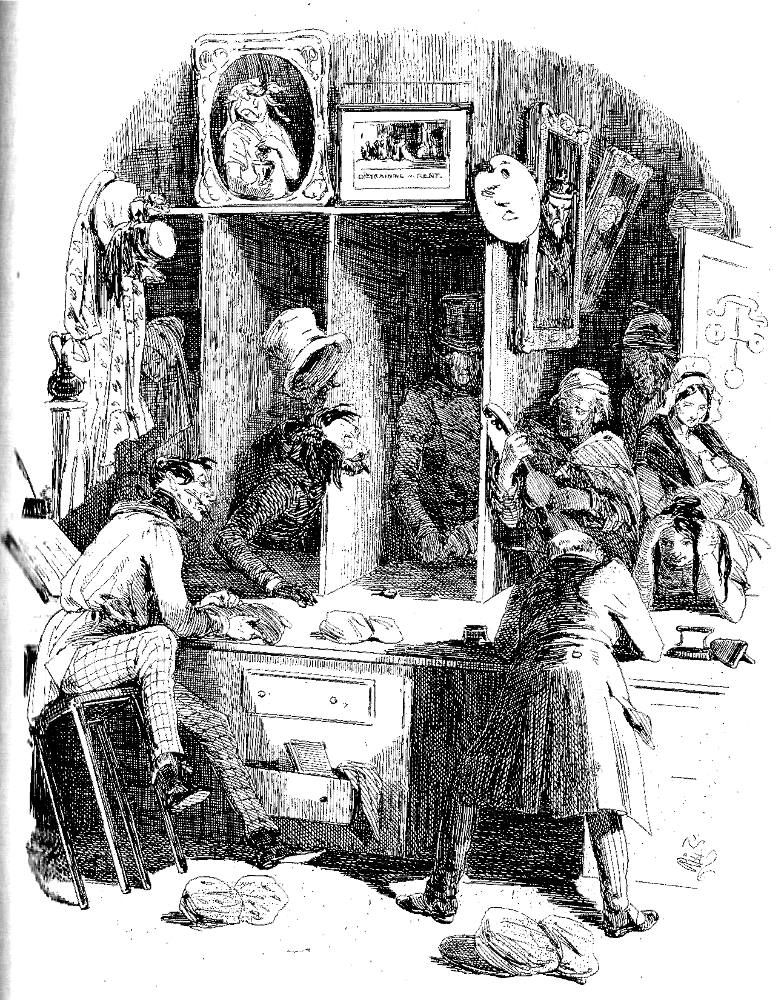

Mr. Brass at the Keyhole. Wood engraving, (8.8 x 11.1 cm. — Part Twenty-three, Chapter 35, The Old Curiosity Shop: 19 September 1840.

If Browne was not Dickens' ideal illustrator for the more heartrending episodes featuring Nell, he was certainly the one to manage a problem of interpretation such as was given to him with the character of the "Marchioness," the scullery maid of uncertain origins and age. Until the novel's last chapter, we are never told how old she is, and she seems at times a very small child and at other times an adolescent (according to the narrator in the final chapter, she is Nell's contemporary, thirteen or fourteen). It is tempting to conjecture that Dickens let Browne into his secret that he intended to make her the daughter of Sally and Quilp, omitting the crucial passage only later, when he revised the proofs (For the most recent reprinting of the excised passages in which the Marchioness' parentage is revealed, see the Penguin English Library edition of The Old Curiosity Shop, ed, Angus Easson (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972), pp. 715-16.). For there is a definite resemblance between the faces of Sally and the "small servant," in the latter's first appearance (in the cut showing them outside the Single Gentleman's door — [ch. 35]). This resemblance is not noticeable in the next cut, depicting Dick spying upon the Marchioness' meager meal (ch. 36), nor is it repeated.

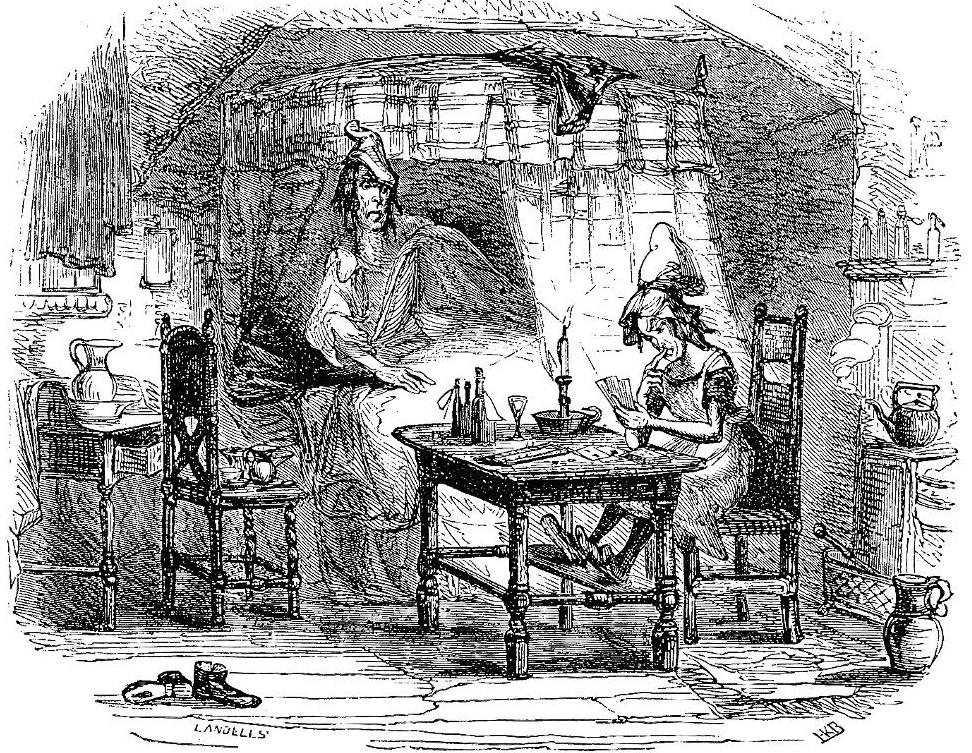

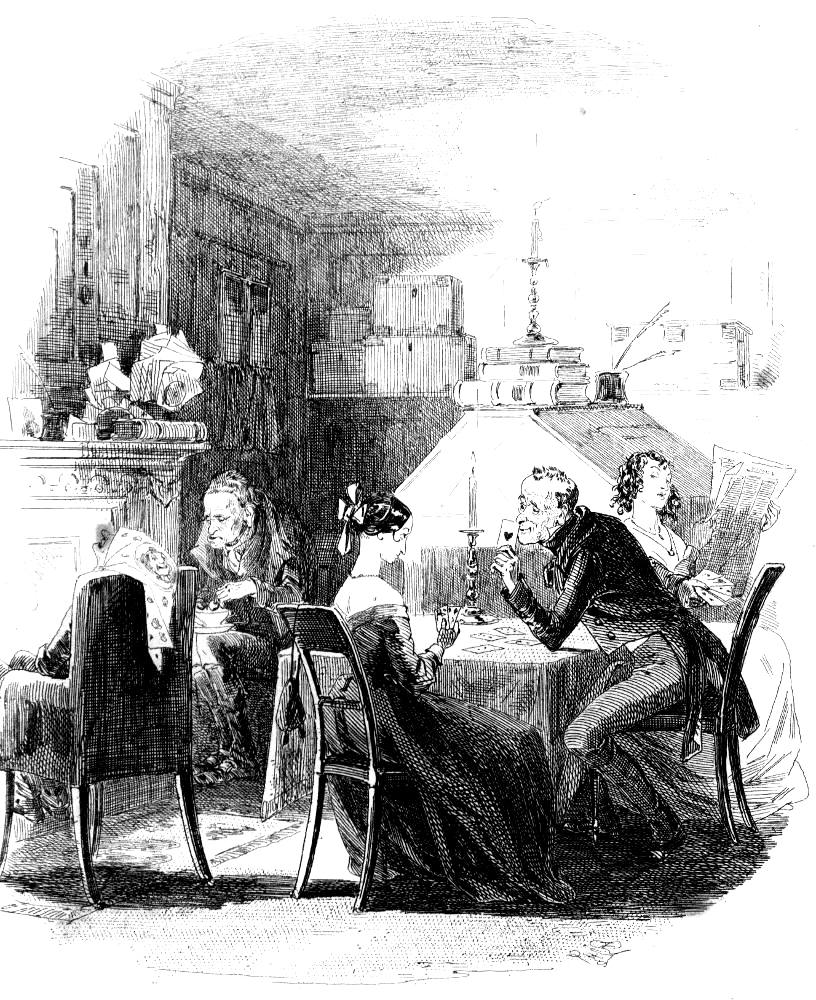

Left: The Marchioness playing cards illustration 34]. Right: The Marchioness illustration 35].

Browne subsequently shows the Marchioness as a wizened creature, looking like a little old woman (the card-playing scene, ch. 57), as a fay-like being (in Dick's sickroom, ch. 64), and as a not implausibly improvable young girl (arriving with edibles for Dick, ch. 66). A few years later, as one in a set of four extra illustrations for the novel, Browne portrayed the Marchioness, supposedly as she was at the sickroom stage of the book, as an attractive girl in late adolescence — less an instance, I think, of Phiz's inconsistency than of his response to the mixed intentions of the novelist in his making the Marchioness the offspring of the demonic Quilp and Sally, a workhouse orphan who has suffered great privations, and yet at the same time a suitable wife for Dick. (See also the reproduction of an initial sketch for this engraving in E. Browne, facing p. 254.)

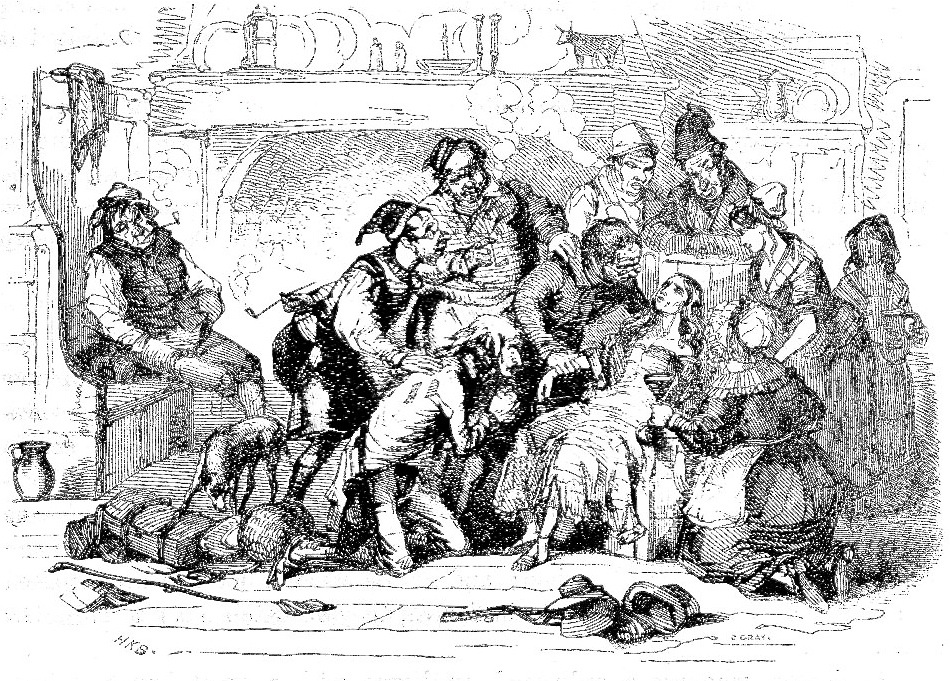

Upper Left: A Parlay with the Card-sharpers (Chapter 42, Part 24: 17 October 1840). Upper right: Watching The Furnace Fire (Chapter 44, Part 25: 24 October 1840). Lower left: Nell in a Faint (Chapter 46, Part 26: 31 October 1840). Lower right: George Cattermole's At Rest (Nell dead) (Chapter 71, Part 42: 30 January 1841).

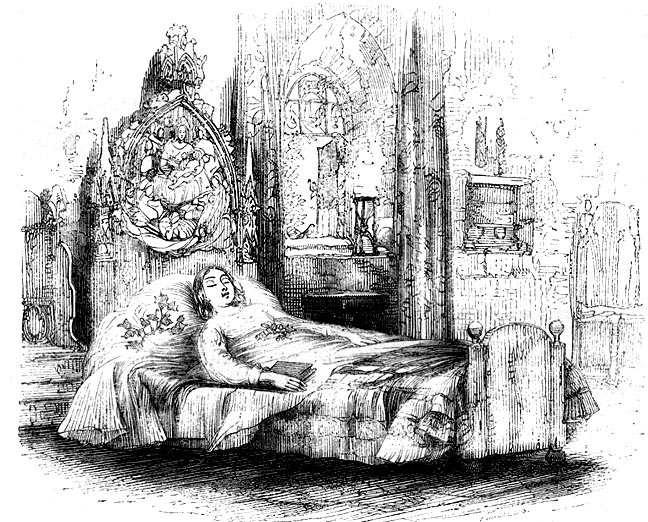

Dickens divided the labor between Phiz and Cattermole very carefully in the later parts of Nell's odyssey through the English countryside. Between Numbers 29 and 31, Nell is brought through the hellish part of her story into a temporary Slough of Despond, and thence to the gateway of Paradise; for the reader she is brought, literally, from the fantasy world of Dickens and Phiz to the fantasy world of Dickens and Cattermole. Phiz illustrates the old man's temptation by List and jowl (ch. 42); his rescue as Nell takes him across on the ferry (ch. 43); the night spent by the furnace (ch. 44) and the rebellious mob (ch. 45), both in the same number; and finally, Nell lying unconscious in the inn, where the schoolmaster has taken her (ch. 46). To Cattermole falls the task of depicting the church and house to which she comes to die, and Phiz has only one more cut including Nell. No doubt Cattermole, in his emphasis on buildings in this series of cuts detailing the end of Nell, came closer to Dickens' wishes than Browne could have done, although the deathbed scene is most distressing in its portrayal of Nell as a kind of proto-Flora Finching (ch. 71). One may see in the architectural emphasis an unconscious corroboration of the Freudian interpretation of Nell's death as a return to the womb — the houses clearly symbolic in this context. The suitability of these illustrations to Dickens'deeper conflicts and fantasies, especially with regard to the death of Mary Hogarth, may explain why he bestowed such effusive praise on Cattermole. One would like to agree with Mrs. Leavis that Phiz "could never have produced" anything "as [55/56] sentimental and religiose" as Nell's "transference to a better world in the arms of the angels" (Leavis, p. 346); but Browne was perfectly capable of his own religiosity and sentimentality, as we can see from the angels in his frontispiece to the second volume of Master Humphrey's Clock. For Browne absorbed many influences besides that of caricature, including Christian iconography, German Romantic art, and the influence of some of his contemporaries among British painters, such as Maclise.

It is, however, as a caricaturist that Dickens regarded Browne at this point. It is possible that Phiz's designs for The Old Curiosity Shop presented Dickens with disturbing visual evidence of his text's implications. Never again do the onginal illustrations for a Dickens novel portray so much low life or so much exuberant energy. The character who epitomizes both is Quilp.

Despite my own Freudian leanings, I have been skeptical of Mark Spilka's description of Quilp's shape as "phallic" (429); yet Browne's Quilp brings out visually what is only implied in the text: his relation, as a dwarf, to the folklore of the "little man," "John Thornas," and the like. (The best known quasi-innocent embodiment of this figure is, of course, Rumpelstiltskin, the hunchback whose power over the miller's daughter lies in her promise to give him her baby.)

Quilp leering at the brasses illustration 36].

Quilp cavorts through sixteen cuts (excluding one by Cattermole and the more quiescent illustration of Quilp's death), five of which, following the text, have him thrusting himself through doors and windows, often preceded by his tall, narrow hat. In another he is shown having gone through a gateway. Elsewhere he is usually engaged in violent or disreputable behavior: leaning back in his chair with his feet on the table, smoking a long, upward — pointing cigar while his wife sits by submissively; sitting on his desk while Nell stands apprehensively near by; smoking in the grandfather's chair with his bandy legs halfway up in the air; beating savagely at Dick, whom he has mistaken for his own wife; rolling on the ground, tormenting his dog; sitting on a beer barrel, raucously drinking and enjoying Sampson's discomfort; and beating at the effigy of Kit. Also in this latter illustration (ch. 16), the figure of Punch on the tombstone is like an incarnation of Quilp as Nell's pursuer; the puppet even looks as though it is making an obscene gesture at Nell (The first but not the second point has been made by Gabriel Pearson, p. 87). The cumulative effect of Phiz's illustrations is to empha [56/57]-size embedded sexual nuances and to bring to the novel the vital energy of comic rascality.

Left: Quilp's Grotesque Politeness (Chapter 60, Part 33: 19 December 1840). Right: The Death of Quilp (Chapter 67, Part 40: 19 January 1841).

But Browne's last two depictions of Quilp mark an important break in the tone with which he is presented in the novel. The portrait of the dwarf (ch. 60), in large scale, stresses much more the malevolent, demonic side of Quilp than his subversive comic grotesqueness. This plate also includes one of the novel's few emblematic inscriptions, "[Accommodations for] Man and Beast." The insinuation about Quilp's evil and ambiguous nature is clear enough. If Dickens gave specific directions for this portrait, one might say it is as though he needed to have Quilp's evil qualities stressed at this point when he was preparing for the comic villain's downfall. With Phiz's design for Quilp's death scene (ch. 67), any trace of Punchinello fun has been eliminated.

When we realize that the number of illustrations featuring Quilp is close to half the total number of drawings for the considerably longer novels in monthly parts, we get some statistical sense of the impact of Quilp's visual presence. Surely, illustrations make it impossible to conceal ftom oneself the dominant role of this delightful villain.

But the visual immediacy of violence and low life in the novel is not limited to the appearances of Quilp. There are the slovenliness and drinking of Dick Swiveller; the monstrousness of Sally and Sampson Brass; the caricaturistic excesses of Mrs. Jarley, Codlin and Short, the gamblers, and even Kit and his mother; the weird vigor of the Marchioness; and the boisterous drinking of Nell's and her grandfather's companions on the raft. What I am arguing is that in The Old Curiosity Shop more than in any of the other novels, Phiz's illustrations — and the more noticeably so in their contrast with Cattermole's — emphasize the unruliness of the energies unleashed by Dickens' imagination. Thanks to Phiz to some extent the illustrated novel is dominated by those energies rather than by the idealizing and religious sentiments which Dickens himself evidently wished to consider the main thrust of the work (one might compare Dickens' later violent reaction to Millais' oil painting, Christ in the House of His Parents, whose realism he considered unsuitable for the subject, in "Old Lamps for New Ones" (Household Words, 1850), Collected Papers, 2 vols. (Nonesuch edition), 1: 291-96).

Dickens has these energies somewhat more under control in Barnaby Rudge, and the evolution of Phiz from an illustrator in the caricature tradition of Cruikshank and Seymour to a nineteenth-century version of Hogarth ("moralized") is well [57/58] under way. However, Phiz still shows uncertainness about his art, so that inconsistencies of characterization are perhaps more noticeable than in The Old Curiosity Shop. Other than Miggs, Sim, and Barmaby, no character stands out as an individual creation, and the handling of Hugh is particularly uneven. Hugh's first appearance is a full-length portrait (ch. 11), achieving very much what the text demands; he is a "poaching rascal," who nonetheless in his "muscular and handsome proportions . . . might have served a painter for a model" (p. 298). In most of the subsequent cuts, Hugh looks more like a conventional comicgrotesque lout, although in his final appearance just before he is executed, he suddenly takes on a rather incredible nobility of feature (ch. 77).

It is difficult to say whether these inconsistencies are a response to Dickens' varying treatment of Hugh, a result of Browne's artistic tentativeness, or simply the fault of the engravers. Certainly the figure of Dennis the hangman is barely recognizable from one cut to another, and he appears in eleven. The illustrations with which Phiz seems to have taken most care are the few portraits of individual characters — especially Hugh and Miggs (ch. 9), whose reptilian face reminds us of the conventions of caricature portraits; Mr. Chester at his ease (ch. 15); and the cuts of Barnaby with Grip the raven (ch. 12; ch. 58).

Phiz makes somewhat more play with emblematic details in Barnaby Rudge than in its immediate predecessor, although there is not yet much of the parallel and antithesis between illustrations that will become so noticeable in his work for Martin Chuzzlewit and beyond. The first instance of such a detail in Barnaby Rudge may provide some insight into the way Browne's invention worked. At the end of chapter 19, Mrs. Varden finds herself stupefied by the variety of food available at the Maypole, and the narrator comments that perhaps even a "Peacock" might be available for a meal. No incident from this chapter is illustrated, but near the beginning of the next chapter, in the same weekly number, we find a cut by Browne with Dolly Varden looking at herself in a mirror which seems to be decorated with peacock feathers. These probably allude to Dolly's vanity, but they may in addition imply the traditional superstition of impending bad luck, for Dolly is shortly to meet Hugh and lose her [58/59] bracelet. It is likely that Browne in this case received his idea through an accidental process of association; such an openness to random inspiration is a cardinal virtue in a man who must produce many kinds of illustrations at so terrific a pace.

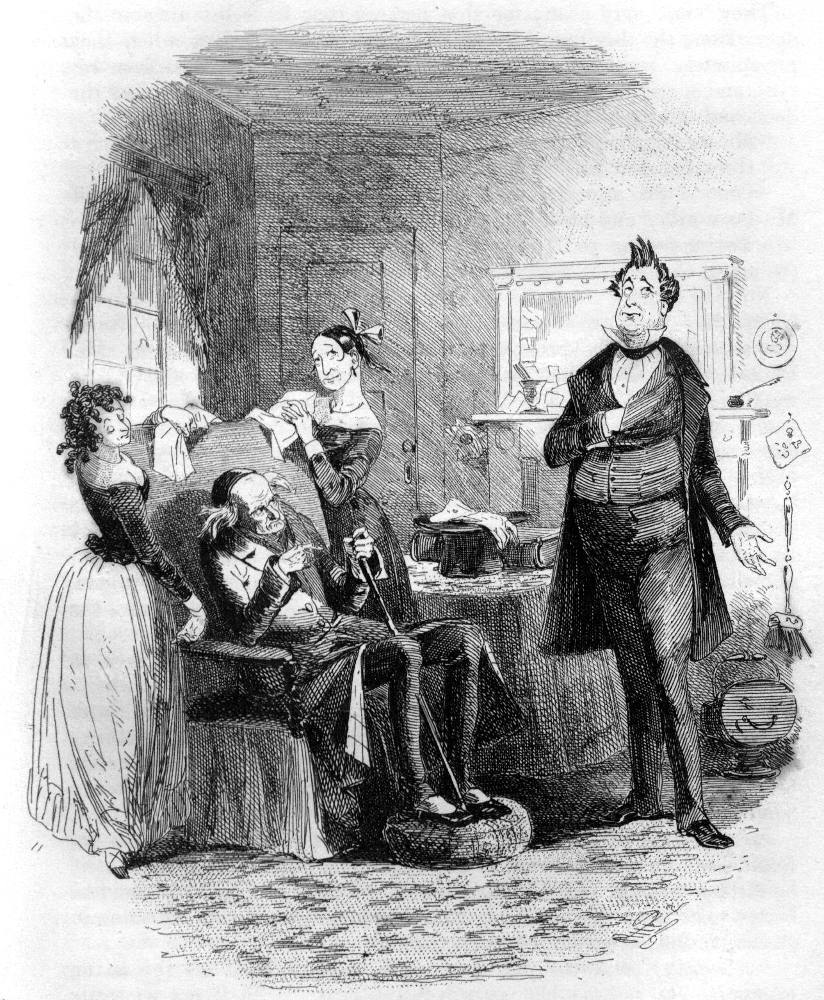

Phiz next uses an emblematic detail in a cut showing Mrs. Varden and Miggs enjoying their moral self-righteousness (ch. 27), while Mr. Chester skillfully plays upon this moral vanity and Sim Tappertit ogles the more honestly vain Dolly. On the chimneypiece is an oval picture of Christ and the children (another version of which decorated the chimneypiece of Master Humphrey in Phiz's rendering, to be replaced at the close of the Clock by Cattermole's rendering of the Good Samaritan) (Browne's tracing of Cattermole's first cut in No. I (Gimbel), also showing Master Humphrey's room, makes it evident that Christ and the children were originally intended for that cut as well, though barely discernible in the cut itself. The Pilgrim editors describe Cattermole's final cut as including a "recumbent full-breasted nude" (P, 2: 382), but although the engraver's rendering is a bit careless, it is in fact clearly the Good Samaritan, whose ironic relevance to the lack of humility, and unchristian self-satisfaction of the women seems clear.

Mr. Chester's Diplomacy [Steig illustration 37].

A few chapters later another biblical allusion is introduced in the scene where Mr. Chester disowns his son Edward for refusing to marry for money instead of love (ch. 32; Illus. 37). Here there is a large painting of Abraham preparing to sacrifice Isaac (a detail which Thackeray later used, verbally, in a parallel situation in Vanity Fair). (The passage occurs in chapter 24 of Vanity Fair. See my article, on Barnaby Rudge and Vanity Fair). The ironic contrast, of course, is between Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his son out of obedience to God, and Chester's sacrificing his son out of pure selfishness; the father's raised nut-crackers and Abraham's raised knife further emphasize the contrast. A similar detail is present in Plate III of A Harlot's Frogress, where, Ronald Paulson has suggested, it is meant to compare ironically God's and man's justice (Paulson, Emblem and Expression, p. 36,), and Browne will use it again in a quite different context in Bleak House. Another detail is associated with Mr. Chester later in the novel (ch. 75), when Gabriel informs him of his bastard son Hugh's incarceration in Newgate, and he is amazed at the lack of "some pleading of natural affection in [his] breast" (p. 379). Upon the wall in the cut is a picture of a woman with two children at her bosom, rather unsubtly captioned "Nature."

The other emblematic details in the Barnaby Rudge engravings are of a comic-grotesque sort. In the depiction of Hugh and Dennis engaging in a wild, "extemporaneous NoPopery Dance" (ch. 38), a sketch is displayed on the wall of a hanged man dancing at the end of his rope, foreshadowing the scoundrels' end. And in another lowly comic cut, where Dennis [59/60] pretends to admire Miggs so as to win her allegiance against her captive mistress, the neck of a dead goose hangs down off a shelf immediately next to the scrawny neck and bosom of the ludicrously vain servant girl, whose face is leering with mock-erotic vanity (ch. 70); the ftinction of Moll Hackabout's goose in A Harlot's Progress, I, is surely similar.

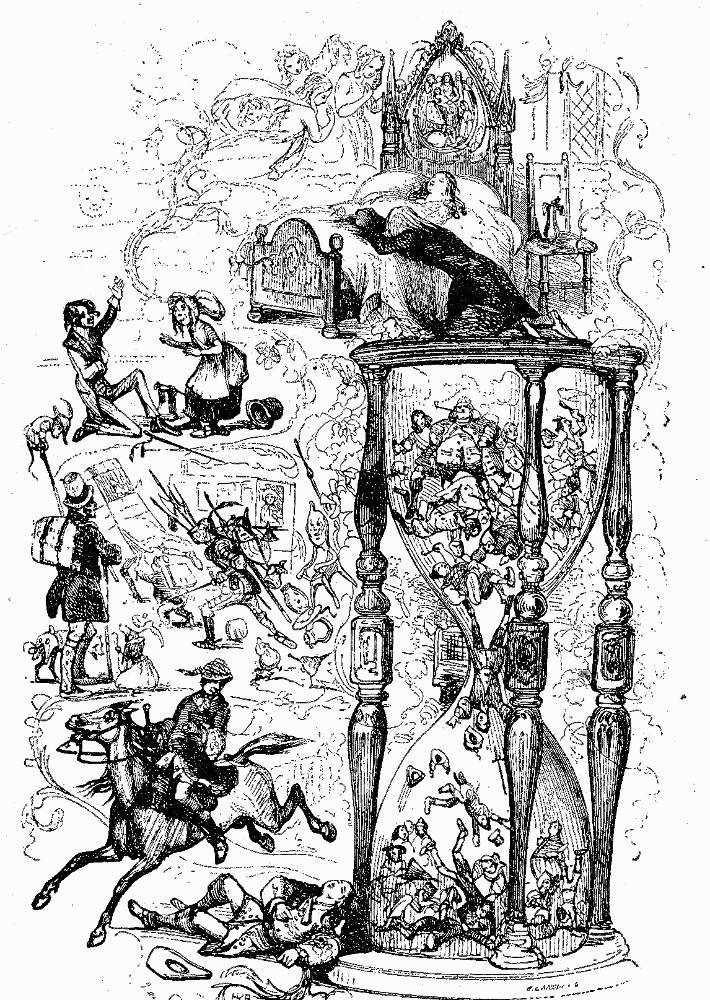

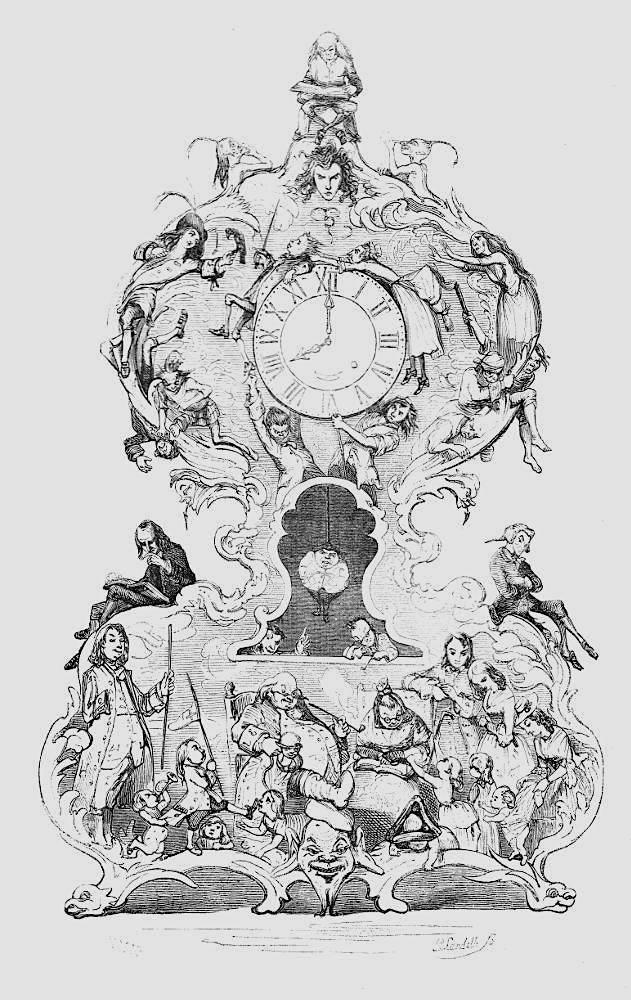

Left: Frontispiece for Vol. II (3 October 1840). Right: Frontispiece for Vol. III (November 1841) for Master Humphrey's Clock.

Perhaps these particular emblems do not represent a high order of interpretation on Browne's part, but they do foreshadow greater achievements. Similarly, the two attractive frontispieces he designed for the Clock (to Volumes II and III), do no more than bring some of the main characters and incidents together within structures based on the idea of the clock. Phiz apparently did not feel very inspired by the last-minute request for the first of these frontispieces, for he wrote to Dickens asking for "some sort of notion of the design you wish." (P, 2: 218.) Subsequent novels by Dickens were to provide more fertile thematic material, and in the next, Martin Chuzzlewit, Phiz develops something approaching a systematic iconography, both in terms of broad allegorical treatment and localized emblems in individual etchings. But on another level, he is to develop a genuinely (and sometimes literally) Hogarthian way of treating the novel as a set of moral progresses.

As Martin Chuzzlewit is near the center of Hablot Browne's series of ten collaborations with Charles Dickens, so it is a crucial turning point in the career of each man. Browne's essential style is established and his ability to interpret the text by means of parallelism, antithesis, and emblematic details emerges brilliantly. And Dickens has for the first time organized a full-length novel around a cluster of moral themes and the moral progress of a central as well as peripheral characters, thus providing Phiz with the inspiration that his particular kind of interpretative talent required. Of equal importance is Dickens' development as a creator of grotesques. Brilliant as a jingle, a Squeers, or a Quilp may be, they belong more to popular comic traditions and to folklore than to the conventions of satirical comedy; Quilp, for example, remains a demon, fixed in a set of grotesque gestures, who evokes ambivalent responses analogous to audience reactions to the Vice character in medieval morality plays (Quilp's derivation from Shakespeare's Richard III has often been noted. For the connection between Richard and the medieval Vice, see A. P. Rossiter, p. 15). A Pecksniff is much more profoundly disturbing because he exists [60/61] within "respectable" society, and mirrors some of its pervasive ethical confusions. He is a figure with a mask, but we never know which is self and which is mask (as Phiz's frontispiece will so beautifully bring out), and from one standpoint he is the quintessence of bourgeois respectability.

Dickens' grotesques thus become more complex, and accordingly Browne's new style loses something of the affinity with caricature defined strictly as the exaggeration of physical characteristics for the purpose of ridicule. In Martin Chuzzlewit's illustrations the figures are less cramped, the faces less grimacing — Mrs. Gamp a notable exception, rendered in the old exaggerated style. To modem critical sensibilities this change may seem more significant than the increasing frequency of emblematic details in the etchings; to some, the moral progress of young Martin Chuzzlewit is a paltry thing compared to the proliferation of great comic characters and the new emphasis upon vivification of the external scene. Yet Martin Chuzzlewit is built upon an essential superstructure of several moral progresses. Without this structure, it is doubtful whether Dickens could have achieved the triumphs of Pecksniff and Mrs. Gamp — just as without Nell he could not have conceived Quilp. Browne's visual and emblematic contributions to this structure are integral to the novel, in the sense that they affect the way we look at the whole overtly moral aspect of the work. It also seems more than a coincidence that the enormous increase of emblematically significant, external details in the etchings should occur at the same time as Dickens' increased emphasis upon external objects — the wind in chapter 2, the view of Todgers's, the Temple fountain — an emphasis which increases steadily in the succeeding novels. Since in his illustrations to Thomas Miller's Godfrey Malvern, a year before Chuzzlewit, Phiz had already begun to rely more heavily on emblematic details, one cannot attribute their presence in Chuzzlewit solely or even directly to the influence of Dickens; rather, it is a sign of the artistic compatibility between Dickens and his illustrator, and of the affinity of their respective careers.

Although the monthly wrapper to Martin Chuzzlewit seems to bear even less direct relation to the novel than does that for Nicholas Nickleby, in fact it sets out a group of general themes [61/62] directly relevant to the novel. Taken together with the frontispiece (appearing in the last monthly part), the wrapper's design is important since the frontispiece applies the cover's imagery to the specific material of the book and completes and makes intelligible the cover's iconography. Together the cover (appearing with every part), and the frontispiece (retrospective in the serial edition because it appeared only in the last installment, but introductory in the bound volume) help yoke the novel and its illustrations into a special kind of unity. This unity is established by thematic rather than sequential links which result partly from Dickens' choices of subject and partly from Browne's interpretations of those choices.

Left: Cover for monthly parts illustration 38]. Right: Frontispiece for Martin Chuzzlewit illustration 39].

The wrapper itself is allegorical, and in some ways typical of Browne's covers for Dickens and other novelists. Like that of Nicholas Nickleby it presents a dichotomy between good and bad fortune, on left and right sides of the design; but it goes further toward establishing the notion of a progress by carrying through a cycle from birth to death. Thus, born in wretchedness, one dies in obscurity (right side); born in luxury, one dies honored (left side). Browne seems to have taken some of his imagery from the novel's full title, which includes a promise to reveal "Who Inherited the Family Plate, Who Came in for the Silver Spoons, and Who for the Wooden Ladles," since silver spoons decorate the footboard of the cradle of fortunate life, while a giant wooden ladle is thrust through the top of the impoverished cradle. Taken by itself without the complementary frontispiece, the wrapper expresses a view contrary to the underlying philosophy of the novel. The figure of a man in the shape of a top who is whipped and taunted by the Fates, as well as the implication that accidents of birth determine one's lot, suggest that fortune is entirely beyond one's control; the novel's thematic purpose, however, stresses the possibility of moral choice from whence one's ultimate condition emanates.

Some of the same details are used in the frontispiece to correct the cynicism of the wrapper and to bring the allegory into line with the explicit moral vision of the novel. The wrapper shows the generalized symbols of cup-and-ball toys: good fortune represented by a smiling ball (which will land in its cup), a bird of paradise, and roses; bad fortune by thorns, an owl sitting on a gibbet, and a suffering ball about to be impaled upon the handle [62/63] of its inverted cup. In the frontispiece, some of these symbols are altered: the hand which held the fortunate cup is revealed as belonging to a beautiful female who supports Tom Pinch's head upon a rose-garlanded cup, while the other hand belongs to a disgusting harpy who impales Pecksniff's head upon a thornentwined shaft. The comic Fates of the wrapper also show up again as hooded females besetting Jonas. On the whole, the parallels between frontispiece and wrapper create continuity: promises are made in general terms at the beginning, fulfilled in the text and plates throughout, and given a final summation and resolution in the frontispiece.

For many modern readers the least interesting, artistically, of moral progresses in Martin Chuzzlewit is that of its eponymous hero. Whether or not one considers Martin's change from a self centered young dandy to a responsible middle-class Christian gentleman to be impressive as an example of novelistic realism, it is in large part upon this young man's development that the novel depends. While the stories (or progresses in the Hogar thian sense) of Pecksniff and Tom Pinch are equal in substance to Martin's and may well be greater artistic achievements, their evolution depends upon the conventional prodigal son story of young Martin; they parallel and throw light upon that story. At the same time, a number of secondary characters also are given "progresses," which in turn reflect upon the three main characters.

The extant evidence (i.e., full instructions for five of the plates) indicates that Dickens chose each subject to be illustrated with great care, and provided a good deal of specific direction; but that same evidence also shows clearly that Browne's freedom to interpret was considerable. Browne used that freedom to make thematic commentary by means of emblematic details, formal parallels between contiguous and scattered plates, character placement, physiognomy, and several kinds of external allusion.

Although young Martin does not enter the novel in person until chapter 5, or the illustrations themselves until Part IV of the serialized version, the ten illustrations to the first five parts, taken together, form a sequence that describes the first stage of Martin's development. This stage is intertwined both thematically and narratively with the progresses of Pecksniff and Pinch. Most [63/64] immediately striking in a review of these ten plates is that the first, the fifth, and the tenth take place in the same room, with Tom Pinch in all three, and Pecksniff and Martin in two each. In the first, Pecksniff is in the center being paid homage by Pinch; in the second, Martin is in the spatial center, enjoying his, own selfish indignation while Pinch mildly attempts to console him; and in the third, Martin triumphs physically over the fallen Pecksniff. Near the center Tom, a concerned and flustered pacifier of Martin, is evidently most confused about his conflicting loyalties to this pair of egoists.

Left: Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and His Charming Daughters (January 1843). Centre: Mr. Pinch and the New Pupil, on a Social Occasion (March 1843). Right: Mr. Pecksniff Renounces the Deceiver (May 1843). Three illustrations for the opening numbers of Martin Chuzzlewit.

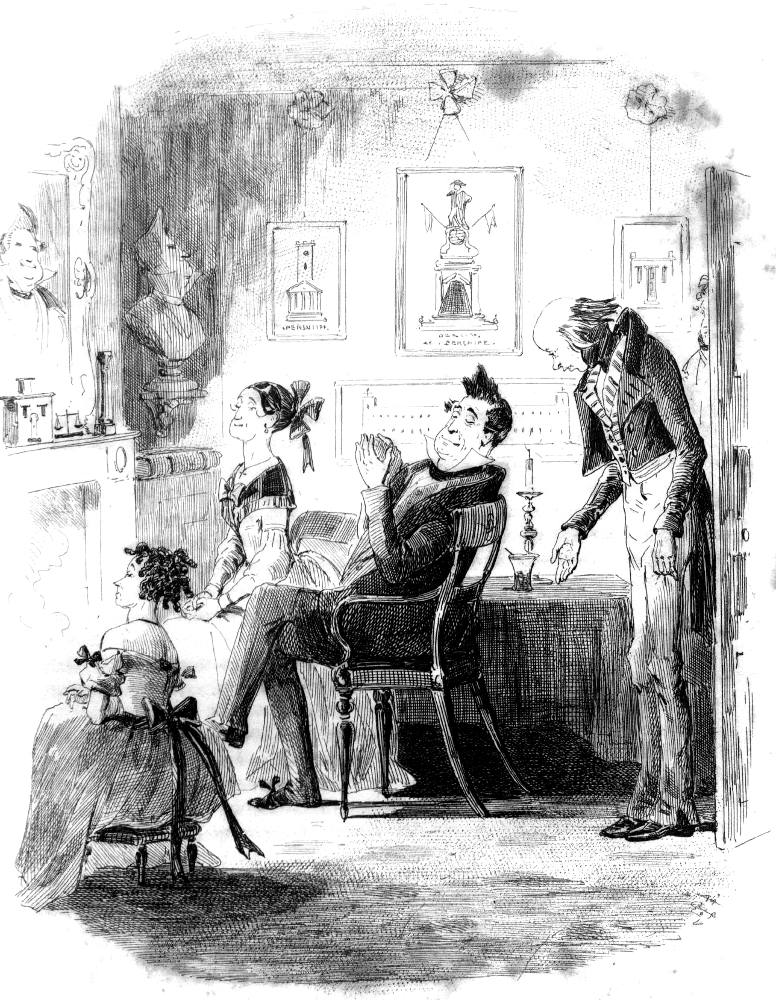

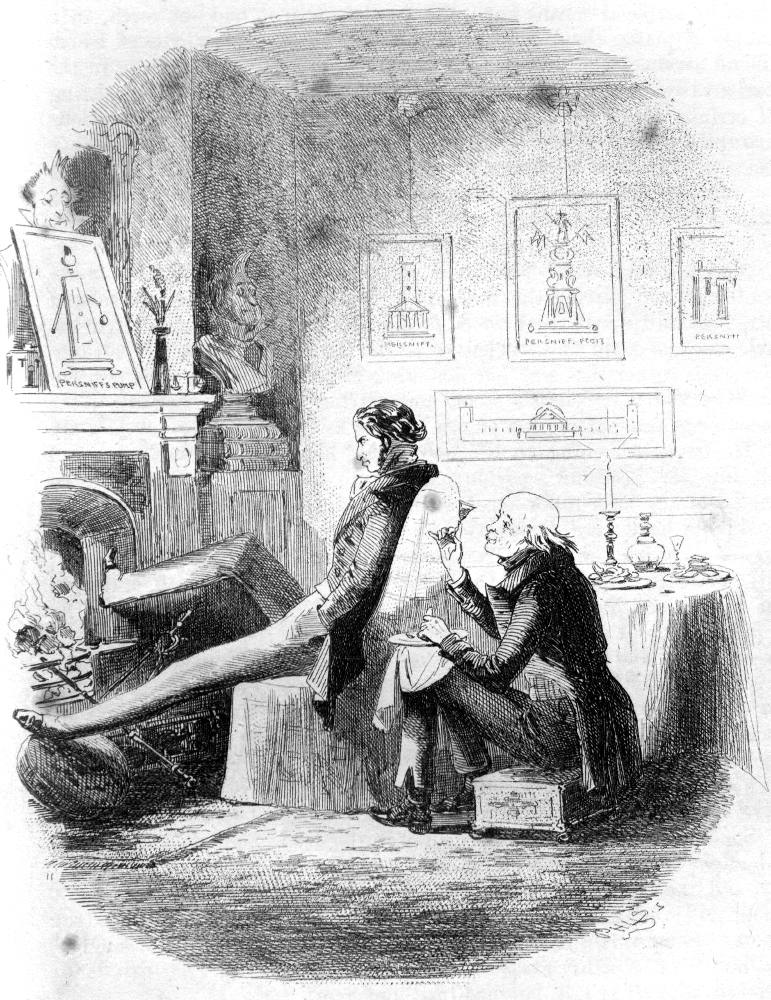

The first of this trio of etchings, "Meekness of Mr. Pecksniff and his charming daughters" (ch. 2), supplements Dickens' text through its marvelous portrayal of smug self-righteousness (anything but "meekness"!) on the three Pecksniffs' faces contrasted to Tom's self-effacement, but in addition it establishes background motifs which will recur in the two subsequent illustrations of the same room. The room is dominated by Mr. Pecksniff through effigies of himself on three sides: the "Portrait . . . by Spiller" and "Bust by Spoker" (not referred to in the text until the next part, ch. 5, p. 61), and the drawings of three architectural designs bearing Pecksniff's name: a large heroic monument and two smaller buildings, one of which is mirrored in the form of the poor box (so labeled) on the chimneypiece. In its latter form, this building (which is probably intended for a workhouse) takes on the appearance of a glowering face, answering the smirks of Pecksniff, his daughters, and his portraits; and whatever evidence of their charity it may provide is also undercut by the presence next to it of a pair of scales, a conventional graphic satirist's emblem for miserliness undercutting as well the religious overtones of the cross around Charity Pecksniff's neck.

On the same chimneypiece is a small, empty vase, whose likely meaning emerges in the central plate of this sequence. In "Mr. Pinch and the new pupil, on a social occasion" (ch. 6), Tom is in charge of the house in Pecksniff's absence, and the vase now contains a flowering plant. The scales are pushed to the very corner of the mantel, the poor box and painting partly hidden. And yet they are hidden by "Pecksniff's Pump," which bears an uncanny resemblance to the master himself (and is probably inspired by the passage in ch. 6, p. 67, in which Pecksniff recom- [64/65] for the budding architect "A pump" as "very chaste practice") (Joseph Gardner, "Pecksniffs Profession: Boz, Phiz, and Pugin," Dickensian, 72 (1976), 75-86, makes a number of interesting points about Pecksniff's career as architect, including the observation that "Pecksniff's Pump" is surmounted bv a flame. It is thus connected with Pugin's scorned modern town pump, which has been transformed into a gas lamp. It seems to me that Browne also may be suggesting that Pecksniff has a head of "gas"!). Thus, Mr. Pecksniff dominates the scene, visually, even in his absence?none of which is in the text, though the general motif of Pecksniff's portraits is the sort of thing likely to have been specified by Dickens.

Plate and study for for Mr. Pecksniff renounces the deceiver illustrations 40-41].

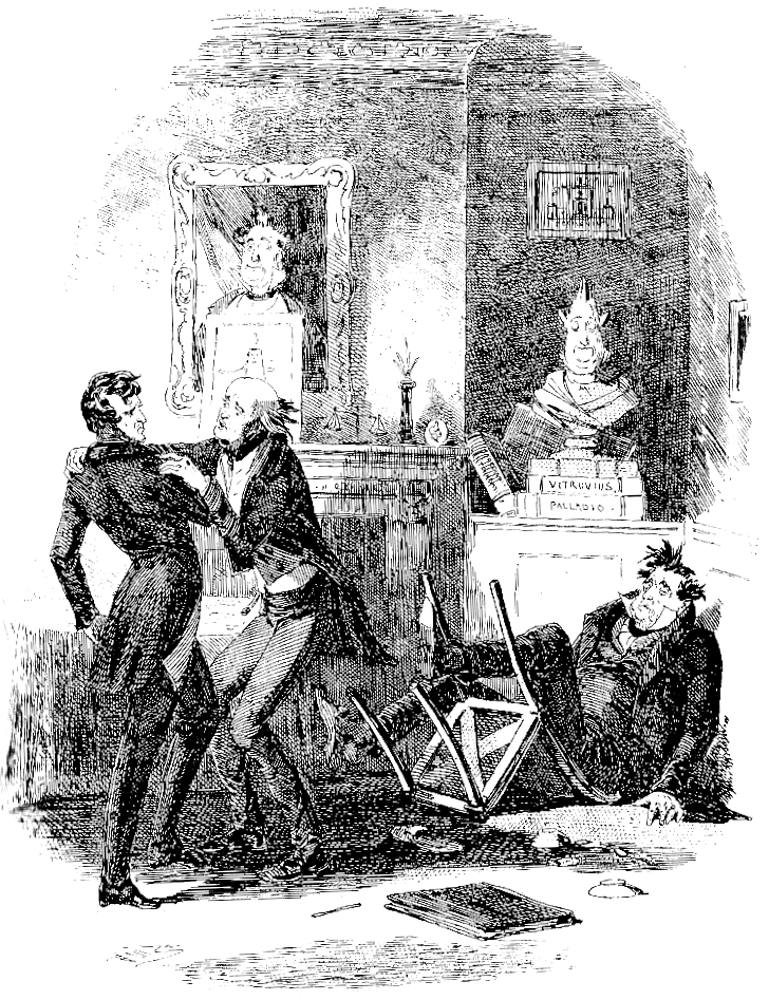

In the third of these etchings, "Mr. Pecksniff renounces the deceiver" (ch. 12), the plant on the mantle has become barren again upon the master's return, but the portrait and bust take on a new function: with the great man now fallen, his hair tousled and his face awry, these effigies seem to smile down upon him, mocking his ignominious position. And in Steel B (numbered as 2, according to Joharmsen (J, 190-91) the scales are now unbalanced, suggesting that justice has temporarily triumphed — a rather ambiguous symbol, however.

Several of the other plates in the first five parts comment by their subjects on young Martin's situation, and also are important iconographically. Thus, "Martin Chuzzlewit suspects the landlady without reason" (ch. 24), centering upon young Martin's grandfather, parallels the first plate through the theme of exclusion, for old Martin suspects and excludes Mrs. Lupin, and his withdrawal from her and most of humanity is expressed graphically by the curtain which divides the plate in two. The parallel is to Pecksniff's exclusion of John Westlock, whose figure is partly visible in the first plate. Old Martin and his grandson, their egoisms and mutual attainment of self-knowledge, are also paralleled throughout the novel.

Plate and study for Pleasant little family party at Mr. Pecksniff's illustrations 42-43].

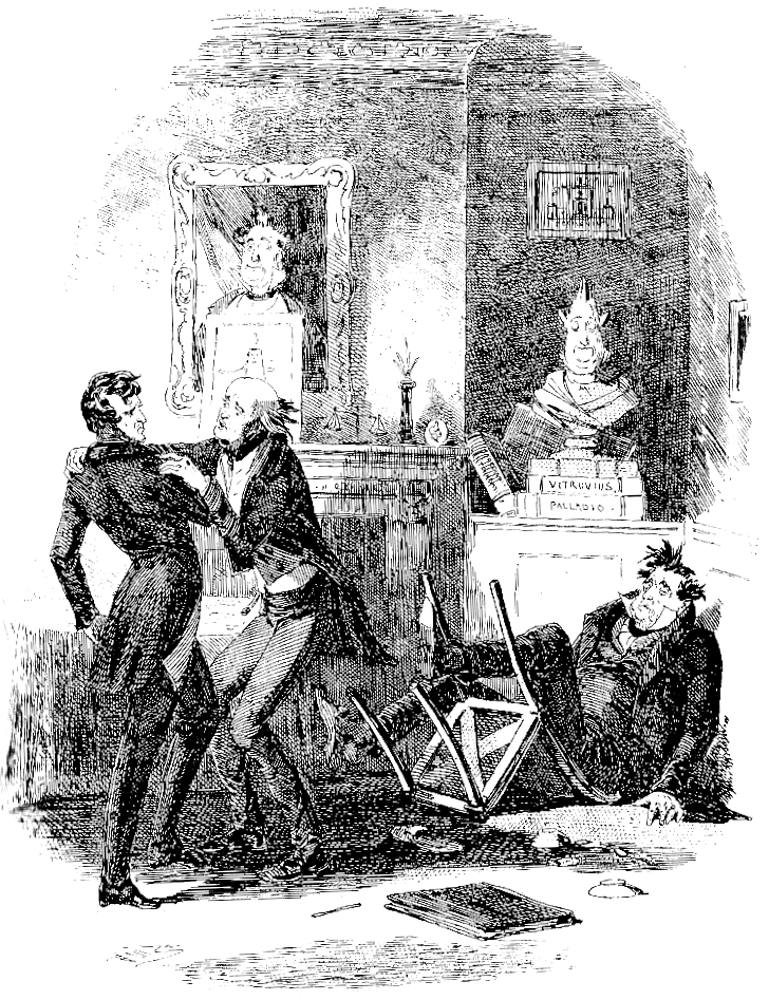

The themes of selfishness and self-importance are reiterated in the two plates in the second monthly part, one of which centers on Pecksniff, the other on young Martin; they contain a single but important visual parallel. "Pleasant little family party at Mr. Pecksniff's" (ch. 4; Illus. 42) shows Mr. Spottletoe's attack upon the great man for arrogating to himself the role of head of the family among the fourteen relatives present. Browne has carefully differentiated the characters, giving Tigg, the hanger-on, a prominent position and having Mercy and Charity react according to their personalities, the former amused and astonished, the latter vinegary and disdainful. Tigg, Pecksniff, and Mr. Spottletoe are further emphasized because the head of each is encircled by the frame of a mirror or picture on the wall; Tigg's [65/66] head is the only one on the same level as Pecksniff's, implying some equivalence between the parasite and swindler and the "moral Pecksniff," but the latter's head is the only one surrounded by a round frame, an ironic imitation of a halo. This "halo" is clearly intended for a convex (reducing) mirror, Which was a common Victorian furnishing often used by Phiz in his illustrations. (Note how the mirror's image, while matching the general pattern of the scene, reverses what a real mirror would show. This reversal is likely a slip, as there are occasional errors in left-right orientation throughout Browne's work.) The reflection resembles a coronation scene, Pecksniff's upright hair looking like a crown and the outstretched arm of the enraged Mr. Spottletoe resembling the arm of a person who bestows the crown. Since Pecksniff thinks of himself as the ruler of the family the image is a fitting one, and the consistency with which Phiz handled this detail in all three steels makes it seem unlikely that it is merely an accident. (It is not, however, present in the working drawing for this plate [Illus. 43].)

It is one of the ironies of young Martin's lack of self-awareness that he in so many ways resembles those he disdains, This irony is brought out in "Pinch starts homeward with the new Pupil" (ch. 5) through the similarity of Martin's head, halfway submerged in its collar, and that of his degraded relative Chevy Slyme — the man he later so urgently wishes to avoid — in the preceding plate. Slyme in his abjectness is the embodiment of total selfishness and is admired as such by the sycophantic Tigg. Thus this plate marks a significant beginning of Martin's progress. But a different sort of parallel and contrast is provided in the second plate for the third monthly part, "Mark begins to be jolly, under creditable circumstances" (ch. 7), which introduces a new character and contrasts Martin's disagreeableness under jolly circumstances (drinking wine before a roaring fire with Tom in the previous plate) with Mark Tapley's supposed jolliness under the gloomy circumstances of leaving the Blue Dragon. Although Mark is certainly not as egocentric as Martin, his self-indulgent "humor" of needing "credit" for being jolly is hardly a selfless condition.

Browne's propensity for interpretation is evident in the [66/67] signpost, an emblem which Dickens and Browne put to various uses. The signpost in this plate points in the opposite direction from Mark's stick and hat, which together seem to express the real direction of his feelings, back toward the village; the fourway signpost is mirrored by the shape of the turnstile that separates Mark from the village. The empty, tipped-over pitcher carried by the little girl could represent either the moral emptiness of Mark's willful abandonment of his community, or the "spilt milk" over which there's no use crying. Finally, the three posters comment on Mark's action: the upper two, "Last Appearance" and "Every Man in His Humour," as theatrical notices imply that Mark is playing a role, and the specific reference to Jonson suggests that Mark's "humour" is as foolish and as in need of deflation as that of Jonson's characters; the third poster, "Lost, Stolen, Strayed/Reward!" again ridicules Mark's need for "creditable" jollity, implying that he is deserting his proper place, like a strayed dog or sheep.

Mrs. Todgers and the Pecksniffs call upon Miss Pinch (April 1843), and Truth Prevails, and Virtue is Triumphant (April 1843).

The novel's first subclimax, the fall of Pecksniff in the tenth plate, is preceded in Part IV by a pair of illustrations centering on the great man in his seemingly most exalted state, making his physical fall all the more degrading. In both "M. Todgers and the Pecksniffs call upon Miss Pinch" (ch.9) and "Truth prevails and Virtue is triumphant" (ch. 10), Browne captures Pecksniff's impenetrable complacency, and in the second he also makes what is to my eyes a curious external allusion: with his hand inside his waistcoat, Pecksniff strikes a Napoleonic pose. His particular stance here, the shape of his body and head, and the hat on the table, bear a remarkable resemblance to Louis Philippe's pose in a contemporary lithograph of the king and his family (See the illustration in Asa Briggs, p. 51). The posture of self-assumed kingliness may be enough to explain the similarity, but it seems possible that Phiz's basic conception of Pecksniff was influenced by graphic representation of the French king, both in portrait and in caricature. In particular, the famous pear shape of Louis Philippe's head, often caricatured with emphasis on the jowls at the bottom and the hair coming to a Point at the top, resembles Pecksniff's head; and the various distortions to which Pecksniff's face is subjected (as in the tenth plate when he cowers in a comer while Pinch restrains Martin) [67/68] recall Philipon's and Daumier's malicious fun with the Citizen-King's face (Harvey shows a Daumier influence on Browne's Mrs. Gamp — Harvey, pp. 132-34.). Apart from the obviously exaggerated expressions on the three Pecksniffs' faces as they crowd around old Martin, the only hint of an undercutting of their "virtue" is the vivified coal scuttle, which grins maliciously.

The bourgeois virtue of the Pecksniffs is only temporarily defeated in the last of the first five monthly parts, for the subsequent travels of young Martin represent what is to him the severe humiliation of having to make his way in the world on his own, without name or connection. Dickens stresses this humiliation with the appearance of the odious Montague Tigg in the pawnshop where Martin seeks anonymity, and in depicting the scene Browne has used both an external allusion and emblematic details. George Cruikshank's etching for The Pawnbroker's Shop in Sketches by Boz is surely the source for Browne's design in "Martin meets an acquaintance at the house of a mutual relation" (ch. 13). In each there is an open door decorated with the pawnbroker's emblem of three balls, and a desk counter with private cubicles. Even the arrangement of figures is the same, down to a workman in a shapeless cap. Phiz's design reverses Cruikshank's as one would expect if he had drawn directly in imitation of the original and transferred the drawing to the steel by his usual method.

Martin Makes an Acquaintance at the House of a Mutual Relation (May 1843) and Mr. Tapley Acts Third Party with Great Discretion (June 1843).

In "The Pawnbroker's Shop," Dickens contrasts working-class and middle-class customers of the pawnshop, while in Martin Chuzzlewit the contrast is between the regular frequenter, Tigg, and the first-time Martin, who feels exceedingly degraded by Tigg's claiming him as a friend. Dickens did not describe the other customers in the scene, and this may be one reason Browne drew upon the Cruikshank etching. He also added two details in the form of a print and a painting: one is an ornately framed bacchante, suggesting Tigg's dissipation; the other is labeled "Distraining for Rent," and is evidently meant to be the much engraved painting by Sir David Wilkie — doubtless a reference to Martin's sorry financial plight.

Mr. Jefferson Brick Proposes an Appropriate Sentiment (July 1843) and The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared in Fact (June 1843).

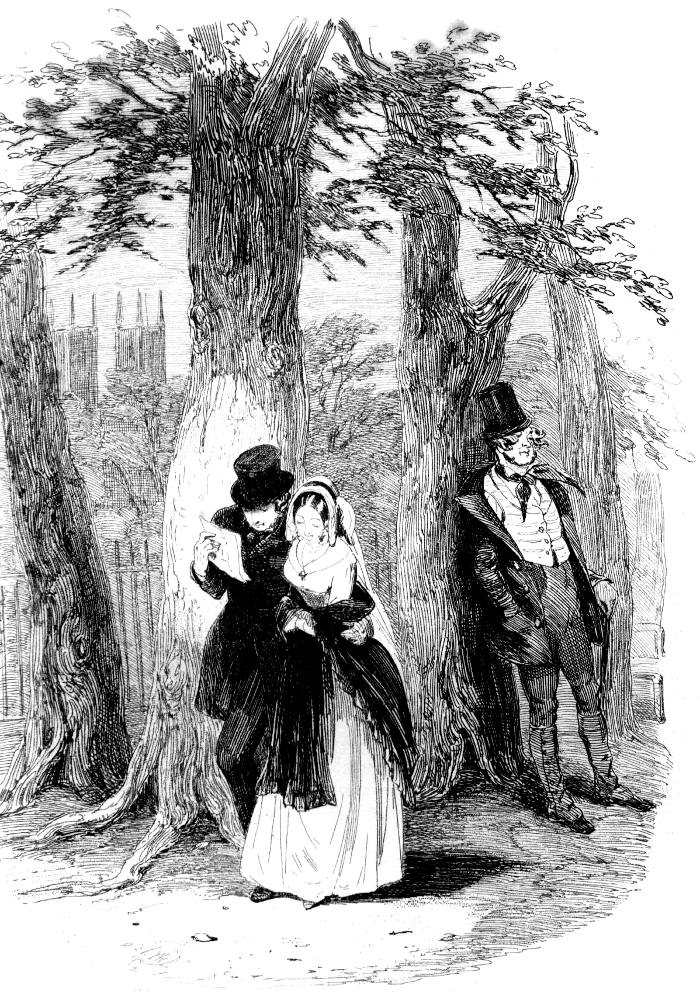

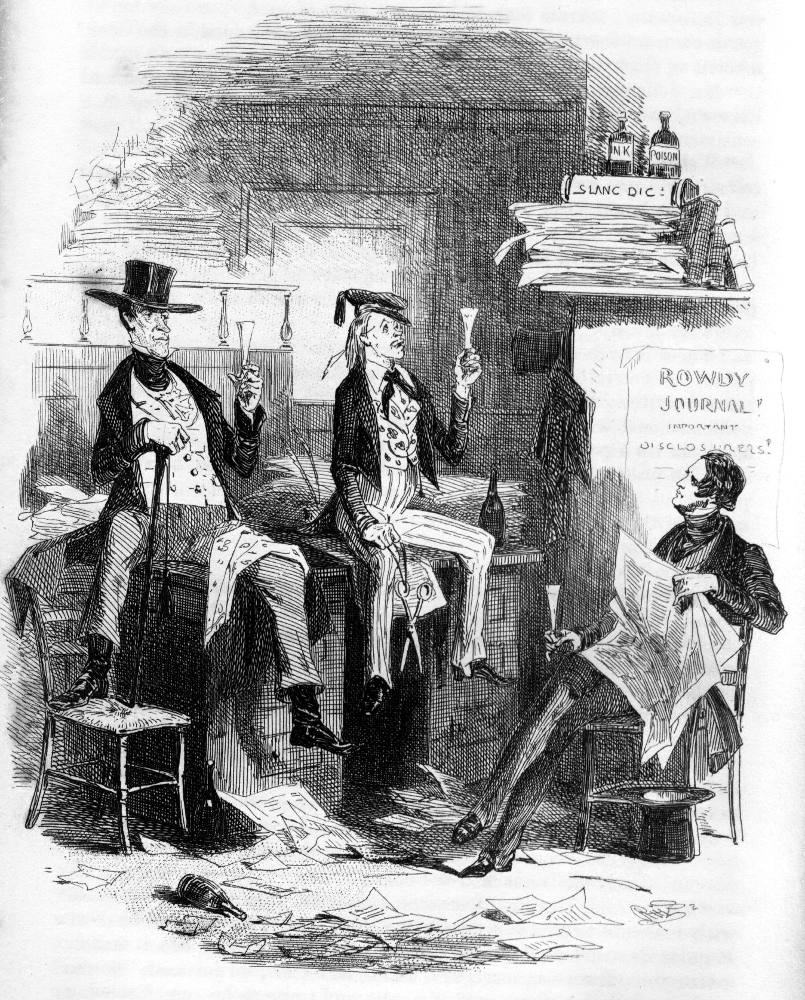

The companion plate and the two for the following part continue Martin's decline to his lowest condition in America. First we see further evidence of his egoism in "Mr. Tapley acts Third [68/69] Party with great discretion" (ch. 14). Despite the fact that his arm is around Mary's waist, Martin is wholly absorbed in fantasies of wealth. Yet the figure of Mark and the towers of Salisbury Cathedral seem to enclose the couple and promise protection and ultimate happiness. The American plates in Parts VII and IX operate by contrast and parallel in depicting Martin's development. In the first, "Mr. Jefferson Brick proposes an appropriate sentiment" (ch. 16), Martin looks quite self-confident, despite the vicious fraudulence of the two newspapermen — underlined by the Slang Dictionary and bottle of poison — and the danger implied in the spider's web at upper left. By contrast, Mark learns something new about the American reality in "Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a 'jolly' subject for contemplation" (ch. 17). Gazing at the nearly destroyed but now "free" slave, Mark's expression and posture belie the boldness of his signature (only initials in the text) on the Rowdy Journal's office door.

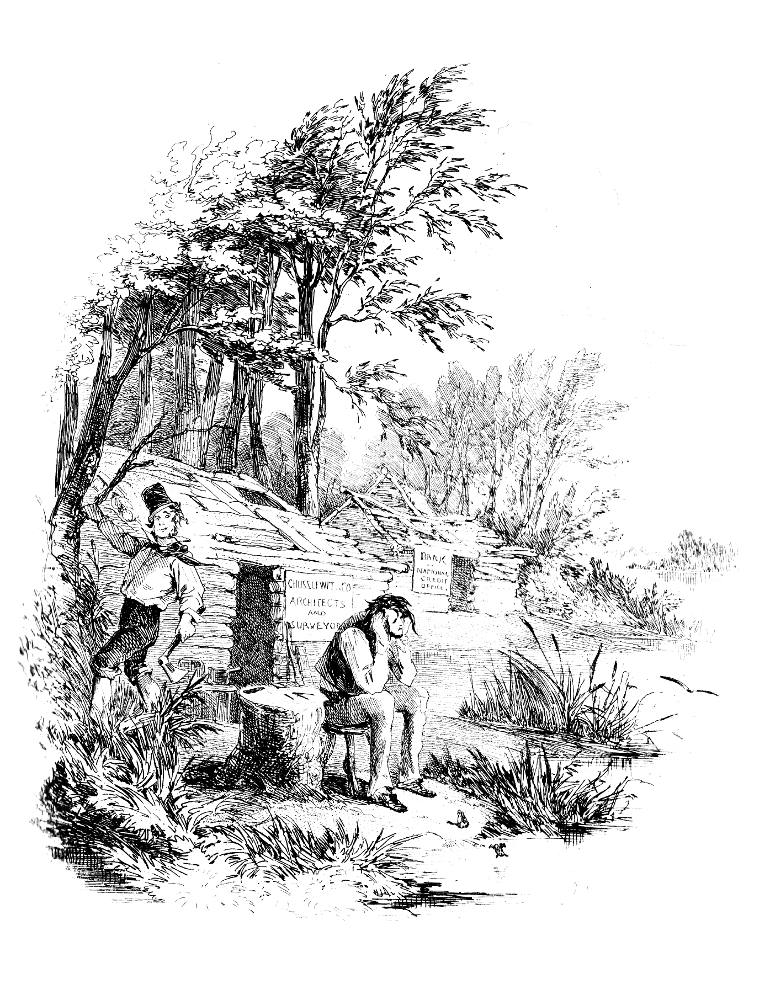

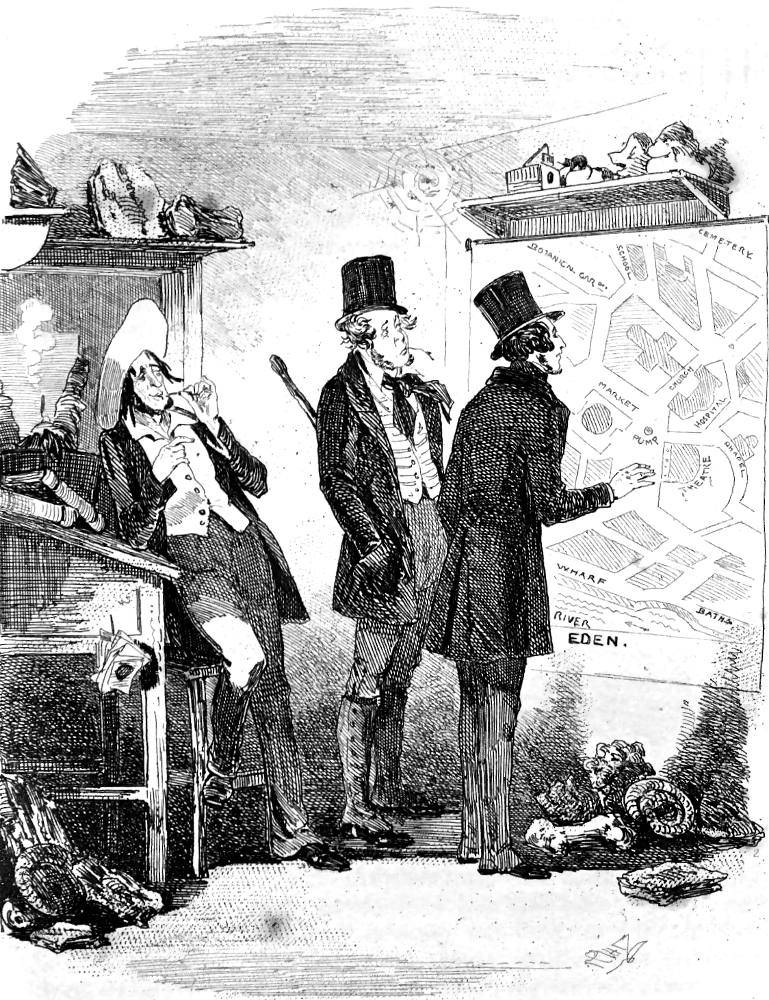

Plate and study for for The thriving city of Eden, as it appeared on paper illustrations 44-45].

Plate and study for Mr. Jonas Chuzzlewit entertains his cousins illustrations 46-47].

The empty spider web in the Journal office becomes a web full of flies next to a mousetrap about to snare a victim in "The thriving City of Eden, as it appeared on paper" (ch. 21), which is contrasted with "The thriving City of Eden, as it appeared in fact" (ch. 23). In the first, Martin retains his optimism and self-confidence while Mark looks on skeptically; in the second Martin is utterly abject and, we find from the text, about to descend into serious illness. In a detailed set of instructions for the latter plate (which has often been reprinted — see John Butt, "Dickens's Instructions"), it is notable how much trouble Dickens took to ensure that Browne achieved his intentions — including material which could not possibly be in the picture itself, such as the rustiness of the compasses on the stump and the intense heat of the day. Yet the two toads or frogs in the final etching (one looking at Martin and the other leaping into the water) are not mentioned in the instructions, and it seems possible that the jumping frog is intended to symbolize the despondent and potentially suicidal reaction of Martin to the real Eden.

During the time that Martin's progress develops apart from the other major characters, the story of Martin's cousin Jonas proceeds both in text and illustrations, and emerges visually as the most important secondary progress in the first half of the novel. [69/70] "Mr. Jonas Chuzzlewit entertains his cousins" (ch. 11) is a visual embodiment of duplicity; it depicts no single incident from the text but rather conflates the reference to Jonas doing card tricks for his guests, the Pecksniff girls, with those paragraphs which make it clear that although he is pretending to woo the elder sister he is in fact aiming at the younger. If we follow a left-to-right "reading" of the plate, we first see Anthony Chuzzlewit in a sleep from which his son wishes he would never awake; next to him is the self-effacing Chuffey, sitting far from the fire. From the dark corner of the room behind Chuffey our eye moves to the strongboxes and ledgers and into the candlelight illuminating the three young persons. Jonas displays an ace of hearts to Charity, who looks at him intently, while behind his back he covertly shows an open hand of cards to Merry, who regards them out of the comer of her eye. We could not have a clearer summary of the situation: Jonas displays the emblem of love, a single heart, to the unsuspecting Cherry, while showing his hand — literally — to Merry. How much of the iconographic invention is Dickens' and how much Browne's is impossible to say, but the plate is typical of the special role illustrations play in Dickens novels: the presentation of meanings which, if made explicit in the text, might seem like clumsy moralizing, premature revelation, or both.

Jonas' next appearance follows the line set out by this illustration in one respect, for in "The dissolution of Partnership" (ch. 18) the subject is his father's death — which he believes to be the result of the poison he administered. That it takes place in the same room as the card trick suggests visually the relation between Jonas' murder plans and marriage plans. The central emblem is suggested by the text and bome out in the illustration:

"Upon my word, Mr. Jonas, that is a very extraordinary clock," said Pecksniff. It would have been, if it had made the noise which startled them: but another kind of time-piece was fast running down, and from that the sound proceeded. (ch. 18, pp. 231-32)

In the etching the clock is prominent, and its hands point just before midnight (in Steel B; in Steel A it is vaguer, but looks more like one o'clock), in emblematic art a common symbol of [70/71] imminent death, or the Last Judgment (Cf. a similar emblem in Abricht, p. 47 (etching by Robert Cruikshank). Mario Praz (pp. 166-68) cites this book as last in a debased emblem tradition. In a sense, the companion plate, "Mr. Pecksniff on his Mission" (ch. 19), also continues the story of Jonas, for it centers on Pecksniff's trip to engage Mrs. Gamp as a "layer-out" of Anthony's corpse.

Mrs. Gamp's alternate function as a handmaiden of birth (upon which the joke of the latter plate turns, Pecksniff being mistaken for an expectant father) is grimly established in "Mrs. Gamp has her eye on the future" (ch. 26). The midwife serves as a disturbing contrast in her grotesque jollity to the actual situation in Merry's new home. The withered branches in the fireplace, a fitting emblem for the marriage, derive from Dickens' text (although it was not unheard of for a novelist to pick up details from his illustrator). The first of this pair of plates, "Balm for the wounded orphan" (ch. 24), returns us to the Pecksniff parlor where Jonas is now the fallen man, having been struck by Tom in self-defense, while the latter perceives his first glimmerings of imperfection in his master's family. Like Pecksniff's fall in the earlier plate, this one foreshadows the character's ultimate de feat. (Browne has done something odd with Pecksniff's physiognomy here, making it much uglier in one steel than the other; it is probably intentional, since the bust of Pecksniff in each case matches the man.)

Left: The Board illustration 48]. Right: Easy Shaving illustration 49].

The story of Jonas becomes inextricably tied up with that of Montague Tigg from Part XI on, and the plates for this part give us a chance to see how effectively Browne could create visual parallels on the basis of the subjects he was given by Dickens. Jonas is one of the admirers — but the only gullible one — of Montague Tigg in his transformation into Tigg Montague in "The Board" (ch. 27); and this transformation is parodied in "Easy Shaving" ch. 29) by Tigg's footman, Young Bailey, who has himself been transformed from the servant boy he was at Todgers's into the flashy pseudo-adult now regarded with astonishment by his old friend Poll Sweedlepipe. The themes of metamorphosis and parody are worked out intricately, for in the first etching Browne parodies the melodramatic pose of "Montague" by a still more pretentious portrait, resembling a distorted mirror image of the already distorted Tigg. The parallels in the companion plate amusingly deflate Tigg's pretense: Bailey is being shaved by the genuinely admiring Poll, although [71/72] his beard — like Tigg's respectability and his capital — is imaginary. Further, just as Montague looks fondly at his own portrait, the puffed-up little footman gazes at a wig wearing his hat, while from the other side a wig block and an owl stare at him in amazement.

Tigg appears in a more sinister form in "Mr. Nadgett breathes, as usual, an atmosphere of mystery" (ch. 38), in which Jonas is the central figure. As Nadgett and Tigg reveal to Jonas their knowledge of his (apparent) poisoning of his father, the glove on the floor appears to be reaching for his throat. The consequence of this revelation, Jonas' first attempt to murder Tigg, is dealt with by Browne in a style different from that of the other etchings in this novel: in "Mr. Jonas exhibits his presence of mind" (ch. 42) he has created a circular composition with Jonas at the center of a whirling vortex, the positions of Tigg and Jonas almost exactly reversed from those in the plate just discussed. The com position here is dynamic, yet compact and formal. although Browne may have been influenced by George Cruikshank's book illustrations, Cruikshank's oval or circular designs usually freeze the action rather than achieving the tension Browne creates. In addition, Browne once again uses visual parallels, making Tigg's gesture echo Anthony's, also on the edge of death, in "The dissolution of Partnership." This parallel is ironic because Jonas' mistaken belief that he has killed his father leads him here to attempt, and later to accomplish, the murder of Tigg.

Browne deals with a comic consequence of Jonas' earlier duplicity with Charity PecksDiff, her pursuit of the unwilling Moddle, in a heavily emblematic style. The incident functions more as comic relief than moral commentary; yet it is important in providing a parallel to the career and downfall of Pecksniff by centering on his favorite daughter, the one who most resembles him in self?importance and hypocrisy. The "courtship" also contrasts with the genuine love relationships in the novel, Ruth Pinch and John Wesdock, Mary and Martin, as well as Tom's unrequited love for Mary.

A parody of romantic love is the theme of "Mr. Moddle is both particular and peculiar in his attentions" (ch. 32), while happy domesticity is mimicked in "Mr. Moddle is led to the contemplation of his destiny" (ch. 46). In the first, Charity casts a proprietary [72/73] look at Moddle, who seems to pull away from Cherry even as he reaches out his hand toward her. The comic but tormenting ambivalence of this reluctant lover is thus admirably conveyed. Three book titles comment ironically upon different aspects of this romance. On the cupboard behind Moddle is Jolly Songs, antithetical to his morose appearance and his sorrow at having lost Merry; at his feet is Werther, the irony of which lies in the disparity between Moddle's implausible threats of suicide and the high-Romantic passions of Goethe's protagonist; and upon the table is Childe Harold, again a story about a quintessential Romantic best known for his world-wanderings, perhaps foreshadowing Moddle's eventual escape to Van Diemen's Land. Sitting on a wall bracket behind Moddle is either a cupid or a cherub, a frequently used detail in scenes of comic disappointed love (cf. the scene of Charity's jilting); here the figure is reading, an appropriate activity for the general sense of this plate that Moddle's behavior is based on books.

As is the case with several of the Chuzzlewit plates, there are two extant drawings for this one, from which we may infer certain things about Browne's typical practices. Both drawings are quite close to the final etching, and both are reversed, but one (Gimbel) is extraordinarily detailed, with far more indication of crosshatching and shading than is normally the case with Browne's working drawings. The other is less detailed, and the indented lines caused by transfer to the etching ground indicate that it is the actual working drawing (This drawing was sold as part of the Suzannet Collection in 1971.). The most likely explanation for the more finished drawing is that it was done by Phiz for himself or Robert Young as a guide to the more precise elements of etching and biting. Red chalk marks the surface, indicating that the basic lines were transferred from the working drawing in the same way as they were to the ground. Neither drawing contains the Jolly Songs detail, which suggests that both precede the process of etching and that Phiz might have improvised emblematic details at the last moment.

Mr. Moddle is led to the contemplation of his destiny illustration 50].

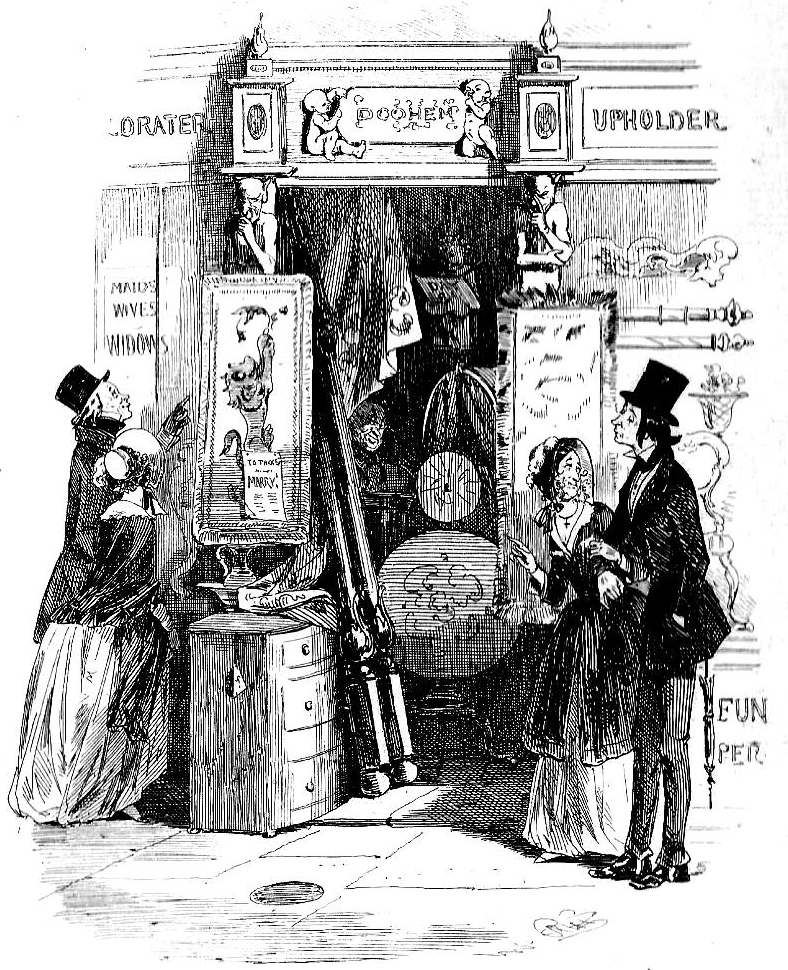

In "Mr. Moddle is led to the contemplation of his destiny", the comic lover is forced to think seriously about his impending marriage, but in the companion plate, "Mrs. Gamp makes tea" (ch. 46), he is distraught at an accidental encounter with his lost love, Merry. In the first, Phiz's imagination multiplies details which carry a good deal of the burden of comedy, for [73-74] the figures of Ruth, Tom, Moddle, and Charity are not as important in conveying the meaning as are the setting and its elements. We gradually become aware that the scene is full of disapproving faces: the rug just behind the couple frowns mightily, while the fire screen in the shop grins maliciously. At the top of each doorpost a satyr or devil looks sideways at Cherry and Moddle, holding a finger to his nose. The comical recording angel, who holds a tablet marked "Day by [Day]," may also be looking at the couple, while the shopkeeper, peering out of the store, has a sly grimace on his face. As if all these faces were not enough, at the left of the door is a sign, "Maids/Wives/Widows" (A similar sign including "To those About to Marry" appeared in a comic plate to Godfrey Malvern ("An unexpected Meeting").) implying that for Augustus to make this — something further borne out by the poster of a lion catching a flying leaf (or a bird?), as if Moddle were being brought down in the freedom of his bachelorhood by a predatory creature. Finally, the customary notice, "To Those [about to] Marry," pinned to the poster, may conceivably have elicited the immediate response from readers, "Don't!" although the first appearance of this joke in print is, to my knowledge, in 1845 (Punch, 8 (1845), 1).

Two preparatory studies for Mr. Moddle is led to the contemplation of his destiny illustration 51-52].

Two preliminary drawings for this plate indicate different initial intentions by Browne, Dickens, or both. One shows Moddle alone, wearing dark glasses (to conceal his identity as Charity's betrothed), and conversing with a shopman outside a furniture shop. The other shows the happy couple walking on the street from right to left, as in the final printed version, and in somewhat the same pose, but with a miscellaneous group of pedestrians and no Pinches or emblematic details. It seems probable that Dickens first gave Phiz general instructions and/or copy having to do with Moddle contemplating buying furniture, and that Browne ultimately combined the pose of Moddle and Charity in the one sketch with the subject matter of the other, perhaps under farther instructions from Dickens.

Because the concluding plate of Charity Pecksniff's progress has interconnections with the other illustrations in the final, double part, I want to defer for the moment discussing her end, and return to the three primary progresses of Martin, Pinch, and Pecksniff. Tom has been present in a number of earlier plates, yet his true graphic progress (as distinct from that in the text, [74/75] where his mental conflicts and doubts about Pecksniff are presented early and in detail) does not emerge as the focus of a series of plates until "Mr. Pecksniff discharges a duty which he owes to society" (ch. 31). The scales fall from Tom's eyes when Pecksniff dismisses him, accusing him of his own recently detected crime of making love to Mary. Pecksniff assumes his imperial pose standing on a step higher than anyone else, which conveys not his superiority but his moral isolation from the others. His facial expression suggests he is an actor on a stage full of real people, for even old Martin — who has been playing a role all along — looks through the window with an expression of concern for Tom. Tom's enormous advance in wisdom is emblematized by a head of Minerva immediately over the doorstep, looking down at Pecksniff.

Tom's next appearance is a step further along the way of his progress, in "Mr. Pinch departs to seek his fortune" (ch. 36). An image introduced early in the novel's text is taken up here and once again in the title page vignette. In his introduction of Pecksniff, Dickens had remarked, "Some people likened him to a direction-post, which is always telling the way to a place, and never goes there" (ch. 2, p. 10); he later emphasizes the actual fingerpost to Salisbury and beyond, which becomes important enough as a symbol for him to exhort Browne not to forget it in the title page. In the present plate it points Tom on his journey, as it had Mark and Martin before him.

Although they at times achieve great insight, the illustrations in Martin Chuzzlewit usually operate on a simpler level of moral commentary than does the text at its most incisive. Thus the four horses that are to take Tom's coach to London in "Mr. Pinch departs .. ." are, unlike the ones that run away with Tigg and Jonas' carriage, tightly controlled by the coachman, although the contrast of the lively coach horses with Mrs. Lupin's staid old mare implies that Tom is starting on a road which will lead him to greater fulfillment in life.

Much of this fulfillment turns out to be vicarious, as Tom watches relationships develop between his sister Ruth and John Westlock (depicted in "Mr. Pinch and Ruth unconscious of a visitor" [ch. 39]), and Martin and Mary. Two plates, however, center on a trial to which Tom is subjected in order to prove his worth. In both "Mysterious Installation of Mr. Pinch" (ch. 40) [75/76] and "Mr. Pinch is amazed by an unexpected apparition" (ch. 50), Phiz again uses the flower symbol of earlier plates. Amidst the dirt and chaos of the room in the former plate is a small vase with a single, flowerless stalk; in the subsequent plate — Tom having replaced chaos with order — the withered stalk has bloomed. And there are other Hogarthian details in the room: the candle covered by a snuffer and the adjacent clock have a spider's web between them, doubtless referring to the neglect of time and light — duty and knowledge — just as Hogarth's cobweb on the poorbox in A Rake's Progress, V, indicates long neglect of the poor in an acquisitive society. In the second etching, Tom has earned the right to meet his benefactor, old Martin, and upon the shelf sits a bust of an elderly man - evidently blind. This image may have come to Browne through his reading of the words in Chapter 50, "and such a light broke in on Tom as blinded him."

This bust turns up again in the very next plate, one of two text illustrations which, together with the frontispiece and title page, fonn the final, double part. The subjects of the plates have been criticized by Angus Wilson as "poor drama," "stagey," and representing a lower level of art than the novel as a whole sustains (p. 178). But if we recognize that the four plates in this last part have an almost ritualistically conventional function (evidently felt by Dickens at this stage of his development to be essential), we may feel these strictures to be misapplied. In particular, Wilson's judgment that the jilting of Charity is a "most unfortunate ending, in irrelevance and inferiority of tone," (Ibid.) overlooks the extent to which the novel has been operating in fairly elementary moral terms all along, and that a dénouement is likely to bring out this aspect of the novel with special force and directness. These four illustrations in fact make the nature of that dénouement clearer than it is in the text alone and, in the last two plates, link it with the general moral concerns of the novel as a whole. The final text illustrations conclude the moral progresses of Pecksniff, Martin, and Tom (although these and Charity's progress are allegorically concluded in the frontispiece, and the beginning of Pecksniff's and Martin's is summarized in the title page etching).

Because the survival of Dickens' directions to Phiz about these four plates gives us a unique opportunity to examine the collaboration between author and illustrator, I shall in discussing each [76/77] plate first quote the instructions (Dickens' instructions for the last two text illustrations, the frontispiece, and etched title page are in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, where they are designated HM 17501. They have been published previously in my article, "Martin Chuzzletwit's Progress by Dickens and Phiz," in Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972), pp, 139, 140, 143, 146, arid are reprinted here with the kind permission of the Huntington Library and Mr. Christopher C. Dickens.). For "Warm reception of Mr. Pecksniff by his venerable friend" (ch. 52), Dickens wrote to Browne relatively briefly in comparison to his extensive instructions for the second "Eden" plate.

The room in the Temple, Mrs. Lupin, with Mary in her charge, stands a little way behind old Martin's chair. Young Martin is on the other side. Tom Pinch and his sister are there too. Mr Pecksniff has burst in to rescue his venerable friend from this horde of plunderers and deceivers. The old man in a [perfect) transport of burning indignation, arises from his chair, and uplifting his stick knocks the good Pecksniff down; before John Westlock and Mark who gently interpose (though they are very much delighted) can possibly prevent him. Mr Pecksniff on the ground. The old man full of fire, energy & resolution.

Lettering.

Warm reception of Mr. Pecksniff by his venerable friend.

At the bottom of the sheet, Browne penciled in:

Mrs. Lupin & Mary — behind Martin's chair.

Yg. Martin on other side.

Tom & his sister.

Old man — Pecksniff

John Westlock & Mark

Despite the prevailing assumption that Browne always acted strictly under Dickens' directions, it is plain from the above that he had a good deal of freedom — and responsibility — to interpret the subjects, and thus, the novel. These instructions are very general, and include more in the way of a novelistic description of character and motivation than of specific graphic pointers, aside from the location of Mrs. Lupin, Mary, and Martin. Notably absent are references to the two books we see in the etching, Tartuffe and Paradise Lost. It was well within Browne's ability to insert these titles on his own, for he must have known enough of the novel, even if he had not read the entire manuscript or printed text, to understand that Pecksniff is a hypocrite (like Tartuffe), and to recognize that Pecksniff has been thrown out of Paradise in the sense that he has lost old Martin's favor and fortune, (It scarcely seems necessary to adduce the bird of Paradise on the cover, or the fact that Paradise Lost is among the [77/78] books on the cover design for Godfrey Malvern, in order to give Browne credit for including this detail.)

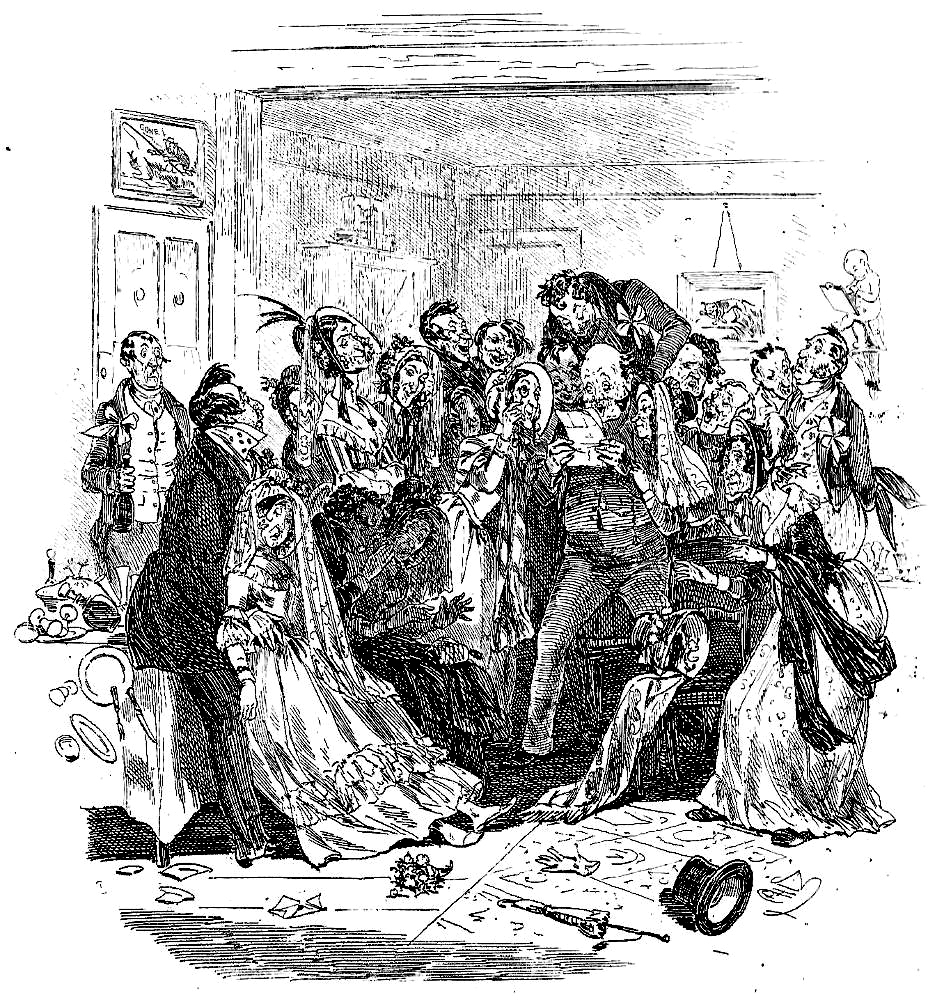

The Nuptials of Miss Pecksniff receive a Temporary Check illustration 53].

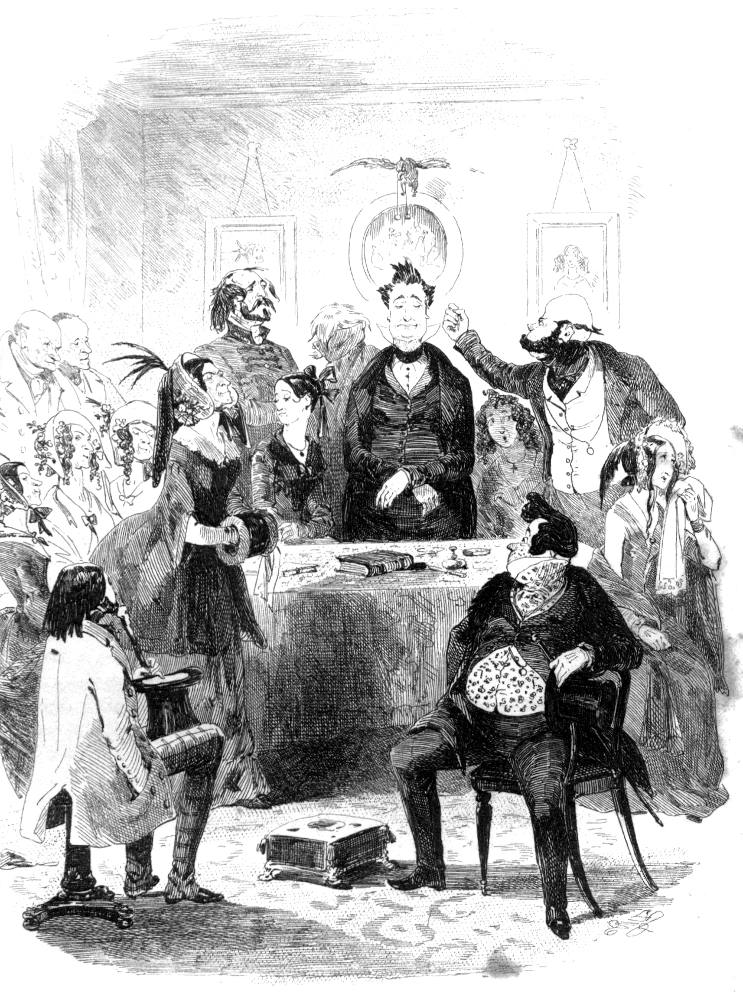

We find Pecksniff fallen and reduced in size in this plate, rather like Louis Philippe in some of Daumier's cartoons, where the Citizen King is subjected to indignities and distortions of person. "The Nuptials of Miss Pecksniff receive a temporary check" (ch.55) provides an obvious parallel in the fall of Mr. Pecksniff's beloved daughter, and on this subject Dickens gives abundant — if not exactly pertinent — information to his artist.

represents Miss Charity Pecksniff on the bridal morning. The bridal [table] breakfast is set out in Todgers's drawing-room. Miss Pecksniff has invited the strong-minded woman, and all that party who were present in Mr Pecksniff's parlor in the second number. We behold her triumph. She is not proud, but forgiving. Jinkins is also present and wears a white favor in his button hole. Merry is not there. Mrs. Todgers is decorated for the occasion. So are the rest of the company. The bride wears a bonnet with an orange flower. They have waited a long time for Moddle. Moddle has not appeared. The strong-minded woman has [frequently] expressed a hope that nothing has happened to him; the daughters of the strong-minded woman (who are bridesmaids) have offered consolation of an aggravating nature. A knock is heard at the door. It is not Moddle but a letter from him. The bride opens it, reads it, shrieks, and swoons. Some of the company catch it and crowd about each other, and read it over one another's shoulders. Moddle writes that he can't help it — that he loves another — that he is wretched for life — and has that morning sailed from Gravesend for Van Deimen's Land. (The strong-minded woman and her daughters are]

Lettering. The Nuptials of Miss Pecksniff receive a temporary [check] check.

The most remarkable thing about this communication is that it contains details (such as colors) and events which cannot possibly be shown in the illustration, some of which are not even in the novel's text, such as the hopes of the strong-minded woman and the consolations of her daughters. Phiz drew a vertical line in the margin next to the last four lines of the note which are extraneous to what an illustrator can depict. Perhaps this [78/79] nondepictable material is not totally irrelevant, since by giving a sense of the drama behind the actual moment the author aided the artist in portraying characters' expressions and physical attitudes. However, Dickens clearly tended to get carried away: the note shows that he was going on still further and checked himself, as though suddenly aroused from his enthusiastic vision of the scene.

Working drawing for The Nuptials of Miss Pecksniff receive a Temporary Check illustration 54].

The parallel between the two fallen Pecksniffs is brought out explicitly only in this pair of illustrations, and Phiz enhances the parallel with emblems. A recording angel once again notes all the absurdities of Cherry Pecksniff, while two prints refer to her losses. In the first, Aesop's dog is about to drop his bone in envy of his own reflection, a suggestion of Cherry's sisterly envy of Merry, who has taken away both "bones," Jonas and Moddle. In the second, a fisherman, whose line has broken, lets a large fish fall; the word "Gone!" appears above his head. This last detail does not appear in the working drawing, and was probably added in the process of etching or transfer (the fact that the letters are reversed in Steel A suggests last-minute haste). One source for the detail may be a comic design by Robert Seymour in his Sketches, published separately in 1834-36 and collected several times thereafter, including an edition in 1843; in it, both the situation and the caption are essentially the same (Seymour's Humorous Sketches ... illustrated in Prose and Verse by Alfred Crowquill (London: Bohn, 1843), n. p.).

The parallel afforded by these two plates makes it clear why Angus Wilson's comments are off the mark. If anything, the allegorical frontispiece centered on Tom and the title page vignette epitomizing Pecksniff are more direct evidence of the conventions within which Dickens worked — especially in this final part. At the same time, a comparison of Dickens' instructions with Phiz's plates demonstrates just how great were both the illustrator's capacity for invention, and the degree of independence he was granted.

— — —

— — —

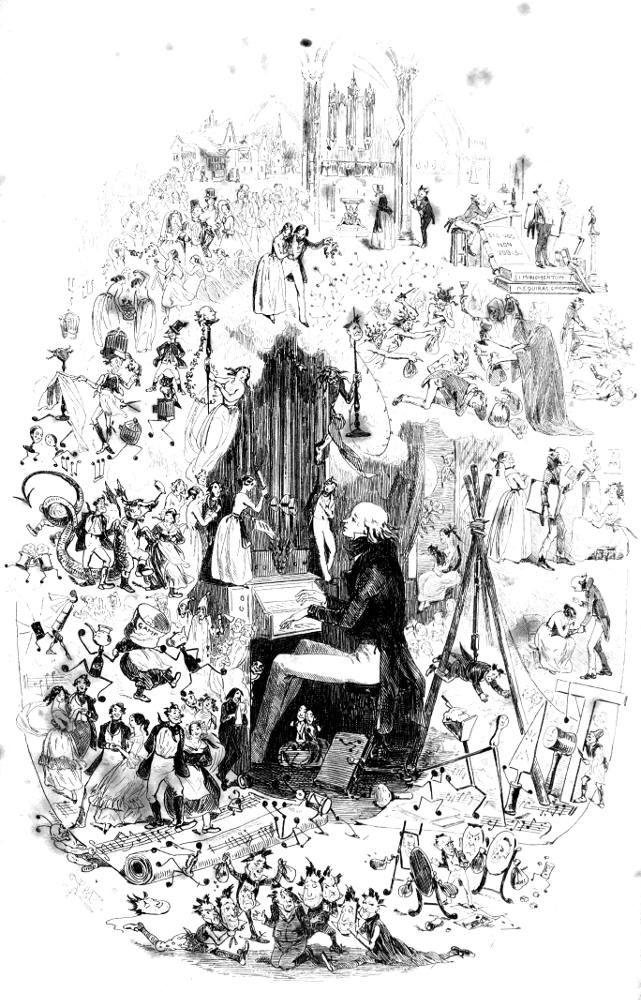

I have a notion of finishing the book with an apostrophe to Tom Pinch, playing the organ. I shall break off the last chapter suddenly, and find Tom at his organ, a few years afterwards. And [79/80] instead of saying what became of the people, as usual, I shall suppose it all expressed in the sounds; making the last swell of the Instrument a kind of expression of Tom's heart. Tom has remained a single man, and lives with his sister and John Westlock who are married — Martin and Mary are married — Tom is a godfather of course — old Martin is dead, and has left him some money — Tom has had an organ fitted in his chamber, and often sits alone, playing it, when of course the old times rise up before him. So the Frontispiece is Tom at his organ with a pensive face; and any little indications of his history rising out of it, and floating about it, that you please; Tom as interesting and amiable as possible.

Given that Dickens had an especially arduous task in writing an instalment of double length, it is not surprising that he jotted down these directions before actually composing the novel's conclusion. Browne, in choosing the "little indications" of Tom's history, went far beyond Dickens' conclusion, epitomizing some of the novel's themes, indicating the resolution of major plot strands (and commenting ironically upon others), incorporating aspects of the wrapper's imagery as well. In the center, of course, there is Torn at the organ, which is decorated with the miniature figures of Ruth and John; above the organ pipes are Martin and Mary, the former holding a bridal wreath, two blossoms of which fall toward Tom. Down the left side a dance motif dominates. Several figures connected with marital bliss are joined by the Blue Dragon himself, and two pint pots dance with Mark and Mrs. Lupin. A female figure with a bandbox head labeled "Gamp" capers with two teakettles as she is observed by three suffering elderly patients and three squalling infants, all presumably victims of her professional skill. Poll Sweedlepipe dances with a vivified dummy and birdcages, while behind him stands Young Bailey, defiantly smoking his cigar (one of the few details not in the working drawing) (The drawing is reproduced in Thomson, p. 66.). Behind three dancing couples at the lower left are a weeping Moddle and a teasing Merry with Jonas (probably) at her side.

Two groups at the bottom represent the destinies of Jonas and Pecksniff. The latter is besieged by snarling images of himself which in turn clutch at smiling Pecksniff masks — a striking way for Phiz to show Pecksniff tormented by his own hypocrisy, The most interesting creation is the smiling figure of Pecksniff holding money bags, who also has a threatening Pecksniff face for a [80/81] belly. The placement of this face is such as to include the genital region, and it would seem to represent the base passions — gustatory and sexual — of the real Pecksniff. The theme of self-confrontation is repeated for Jonas, who is surrounded by his own reflection in mirrors that hold bags of money. Above this, Pecksniff is shown again, hanging in a horizontal position from a block and tackle borrowed from an earlier illustration in which Mark and Martin attend, unrecognized, the honoring of Pecksniff for what are really Martin's architectural designs ("Martin is much gratified by an imposing ceremony" [ch. 35]). Now literally hoist with his own pretense, Pecksniff watches helplessly while vivified implements of the builder's trade cavort below him. Above this scene Jonas once again is besieged, now by skeletons, medusae, and Fates, who hold out money bags and glasses (of poison) to him. Between the suspended Pecksniff and Jonas is Charity as an old maid holding a cat; she is looked down upon by a moon and an owl (the latter recalling the owl in the bad fortune side of the monthly cover).