ickens' seventh novel is at once less complicated and more complex than his sixth. Instead of Martin Chuzzlewit's proliferation of subplots and groups of characters mirroring one another in rather abstract ways, in Dombey and Son Dickens carefully relates moral, social, and psychological themes, purposefully rather than in hindsight. His penetration beneath the brilliant linguistic surface is also deeper. Although the novel pivots on the moral progress of Mr. Dombey, the fact that his evil has social ramifications means that his individual development does not become the primary point of reference. And Mr. Dombey is at once the source of Paul's and Florence's difficulties in childhood and his own ensnarement in a tangled set of conflicts regarding power and sex. Browne's most important illustrations bear on these topics, and at their best they interpret and illuminate in ways more subtle and profound than do those of Martin Chuzzlewit.

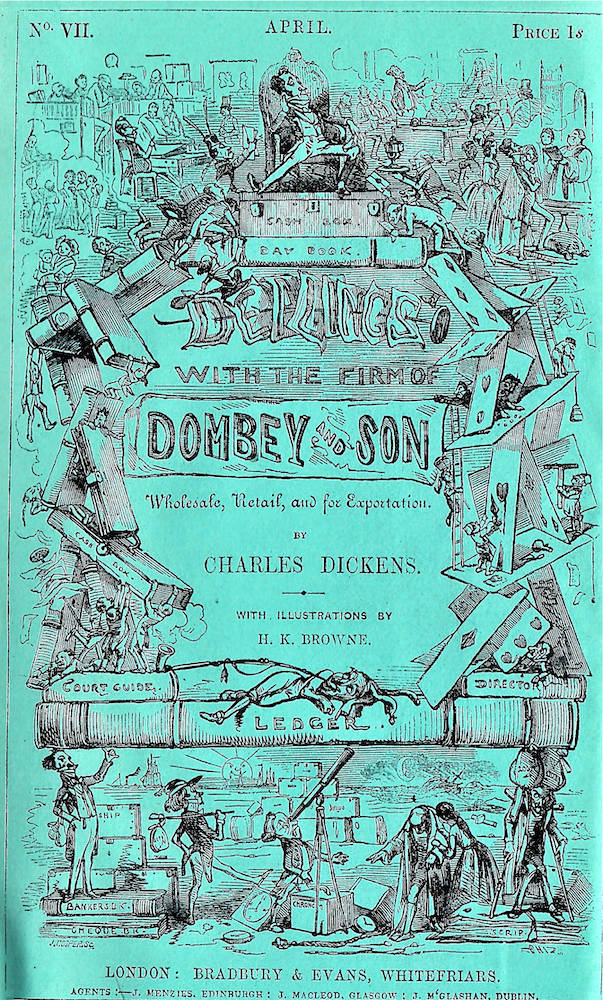

Cover for monthly parts, Dombey and Son illustration 59]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

The new dimensions and assuredness of Dickens' initial formulation of his themes are strikingly visualized in the cover design for Dombey and Son especially in contrast to that for Chuzzlewit. As usual, we cannot know how much guidance Dickens gave Phiz in the particular allegorical conception of the design, but he must have revealed a good deal about his plans for the novel; the wrapper includes references to Dombey's commercial career and the ultimate fall of his business, to his marriage, [86/87] to the birth and schooling of Paul, to a young man setting out to sea and being shipwrecked, to the Wooden Midshipman, and to one of the last episodes in the as yet unwritten novel, Florence's care for her shattered father. Although Dickens felt there was a little "too much in" the design, it is on the whole fairly unrevealing of the plot and conceived in traditional imagery and structure (N, 1: 787.). There is no reason to think that Browne could not, given the requisite hints about Dombey's personality and the commercial themes of the novel, have composed out of his own imagination and stock of visual ideas the central allegory as we have it.

The fool with cap and bells, lying on the ledger, is a traditional figure Phiz reverted to more than once in his monthly covers; here, the fool's pipesmoke "dreams" the rising and falling structure of the design. The proud Dombey sits above on a throne, but his Cash box and day book are supported by an edifice of ledgers which is no more substantial than the precarious structure of playing cards paralleling it on the right. A structure on the point of collapse will be hinted at in the Bleak House cover, but here it is the most effective element in a design which is otherwise full of details that could have meant little at first to the original readers. When the novel was completed, Browne produced an allegorical frontispiece more closely related to the body of the novel, yet it omitted the commercial theme altogether. Thus it is difficult to say whether we should consider the two designs complementary or must rather conclude that there is some disjunction of purpose. The commercial theme as such is never adverted to again in the plates to this novel, whose subjects, as usual, Dickens specified; but careful reading of the plates and their interconnections shows that they do emphasize and complement Dickens' social vision.

From the beginning Dickens was almost as concerned with the illustrations as with the text; as be wrote to John Forster,

The points for illustration, and the enormous care required, make me excessively anxious. The man for Dombey, if Browne could see him, the class man to a T, is Sir A_____ E_____, of D_____'s. Great pains will be necessary with Miss Tox. The Toodle Family should not be too much caricatured, because of [87/88] Polly. I should like Browne to think of Susan Nipper, who will not be wanted in the first number. After the second number, they will all be nine or ten years older; but this will not involve much change in the characters, except in the children and Miss Nipper [N, 1: 768]

The implication that the Toodles might have been caricatured, were it not that Polly is a wholly sympathetic character, is evidence of how Dickens' changing purposes operated upon Phiz's development as an illustrator, for indeed the style of the etchings is less caricaturistic than in Martin Chuzzlewit, one result of which is that the grotesques — in particular Major Bagstock and Mrs. Skewton — stand out in sharp contrast to many of the other characters, although at times, as with Mrs. Pipchin, Browne was seemingly not enough of a caricaturist for Dickens.

Up to the point of little Paul's death, in Part V, the illustrations form a unified sequence, but thereafter they reflect the novel's bifurcation into the worlds of Dombey and the Wooden Midshipman, with Florence moving between them. A single theme dominates the early plates relevant to the first of these worlds, while those in the second offer thematic counterpoint. Paul is naturally the central figure in the early plates, but Browne attempts more than merely to record his development: in Part I the illustrations contrast the Toodles and Dombey families at the same time as they show the relationships which grow up between them. (Dickens' number plans include the two captions actually used, plus a third, "Mr. Dombey keeps an eye upon Richards," which is partially descriptive of the Second plate. See Horsman's Clarendon edition, p. 835). Without its companion, "Miss Tox introduces 'the Party'" (ch. 2) would seem no more than a stilted lineup of the Toodles, Miss Tox, and Mrs. Chick; but as soon as we look at "The Dombey Family" (ch. 3), the importance of the first plate becomes apparent. In both plates Polly stands left of center holding a baby in the same position, and in both the muffled chandelier, a "monstrous tear depending from the ceiling's eye" (ch. 3, p. 16), is present. But the first plate characterizes the Toodles by their physical closeness and contact; in the second plate the Dombeys are epitomized by the spaces between them. Paul is close only to his nurse, who stands at a respectful distance from her employer. Florence is separated from Paul by her father, and from her father by a wide space; as Mrs. Leavis points out, she is even outside the door frame (Leavis, p. 350.). While the precise scene is not described in the text, no one before Alan Horsman had recognized that Dickens, in choosing this version over the one Browne [88/89] drew with Dombey standing, elected to have the artist differ from the text. The original drawing, with Dombey standing (Dexter), is reproduced in the Clarendon edition, facing p. 865. For this drawing and several of the other early ones in Dombey and Son, Phiz used pen and (blue) ink, but for the working drawings he went over the lines with a blunt point. The effect on the style of the drawings — though not the etchings — is very noticeable, and one might conjecture that Browne was attempting a different kind of line. (It is also possible that he was temporarily out of pencils!). It is as though the illustrator's attempt to present the author's original conception forced the author to recognize that he had not adequately expressed his own inner vision. Phiz's version rather than Dickens' — which was not altered to fit the illustration — is the one that remains in our memory.

The thematic contrast of the first two plates is carried farther in the illustrations for Part II, "The Christening Party" (ch. 5) and "Polly rescues the Charitable Grinder" (ch. 6). While the first pair compares the newest Toodle and the newest Dombey, in the second the infant Paul is juxtaposed to Polly's oldest son, Biler, who is about to be saved by his mother from a hostile mob of children. Since both boys are under the aegis of Mr. Dombey (who has arranged for Biler's education and thus for his consequent humiliation), perhaps the point is as much an ironic parallel as a contrast: on the surface the difference between the loved and pampered child of a rich man and a coldly patronized poor man's child is shown, but on another level we see in both the tendency of the Dombey influence to blight and wither.

Preliminary study and published plate: Paul and Miss Pipchin illustration 60]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

This tendency is illustrated in the first of several plates dealing with Paul's childhood, Paul and Mrs. Pipchin (ch. 8), perhaps the most celebrated etching in the novel, if only because Dickens is on record as having been violently disappointed with it [the much-quoted letter to Forster is in The Letters of Charles Dickens (1938, 3 vols.), edited by Walter Dexter, 1: 809]. Dickens seems to have objected because Paul is sitting in the wrong kind of chair, and Mrs. Pipchin should be stooped and much older, although according to Mrs. Leavis, the whole atmosphere is not uncanny enough, the witchlike and magical qualities of the text insufficiently realized (Leavis, pp. 352-53). Yet Browne was presented with special problems as an interpreter. The description of Mrs. Pipchin is, if taken straight, quite extravagant: she is a "marvelously ill-favored, ill-conditioned old lady, of a stooping figure, with a mottled face, like bad marble, a hook nose, and a hard grey eye, that looked as if it might have been hammered at on an anvil without sustaining any injury"; she is an "ogress and childqueller" who likes hairy, sticky, creeping plants, and whose waters of gladness and milk of human kindness had been pumped out dry" (ch. 8, p. 72). The description of the scene depicted in the fifth plate concludes that "the good old lady might have been — not to record it disrespectfully — a witch, and [89/90] Paul and the cat her two familiars, as they all sat by the fire together" (pp. 75-76). Dickens may have been upset because the plate (whose drawings he evidently did not get to see) failed to match his own inner vision. Forster remarks that Dickens "felt the disappointment more keenly, because the conception of the grim old boarding-house keeper had taken back his thoughts to the miseries of his own child-life, and made her, as her prototype in verity was, a part of the terrible reality" (2: 29). Browne can certainly be faulted for not getting the chair right, but one must ask how an illustrator is to deal with semifacetious suggestions of the uncanny and supernatural when he is illustrating a purportedly realistic novel. Surely he is faced with the problem of embodying a sense of the author's description without suddenly shifting his style into a more fantastic one.

The drawings for Paul and Mrs. Pipchin give evidence that Browne worked hard to get this illustration right. The initial sketch (Dexter) is a free ink drawing, with the figures facing the same way as in the printed etching (the sketch is reproduced in the Clarendon edition, fac. p. 866.); the number of comparable drawings extant is small enough so it seems reasonable to assume that when Phiz did make such a sketch he was especially concerned about the left-right arrangement, as in the vignette title for Martin Chuzzlewit. In this case a look at the working drawing, reversed as usual, reveals that the placement of the figures makes some difference. With Paul on the left, as in the etching, he catches our attention first, and only then do we notice Mrs. Pipchin; with the figures reversed, Mrs. Pipchin dominates: looking from left to right we see first her creepy plants, then her looming figure, and only third little Paul. The printed version and the initial drawing cause us to see Mrs. Pipchin more through Paul's eyes; the author's description of her then may be understood to take some of its fairy tale quality from that viewpoint. Browne seems to me to have been as successful as possible in his attempt to combine a realistic with a fantastic atmosphere, and it should be mentioned that Mrs. Pipchin's expression is a good deal more frightening and witchlike in Steel B than in Steel A, though it is the latter which most resembles the working drawing — suggesting that Browne was still experimenting with La Pipchin down to the last minute.

The companion etching, "Captain Cuttle consoles his friend" (ch. 9), takes us from the harshness of Paul's Brighton environment to the protections of the Wooden Midshipman. Visually, the parallel is between Paul sitting in his chair looking up apprehensively at the old "child-queller," and Sol Gills sitting in [90/91] his chair being comforted by his nephew and Captain Cuttle. although the basic point may be one of contrast, both Paul and Sol are "old-fashioned" in slightly different senses: Paul, we discover, seems precocious because he is so close to and intuitively so aware of death; Mr. Gills is old-fashioned in the present sense of being, as he says, behind the times. In both there are overtones of enfeeblement and decline.

Dr. Blimber's school finishes off, in the next three plates, what was begun by Mr. Dombey in dismissing Polly, and continued by sending Paul to Mrs, Pipchin. For "Dr. Blimber's Young Gentlemen as they appeared when enjoying themselves" (ch. 12), Dickens' surviving instructions show us how much Browne was able to contribute to his collaboration with Dickens. The larger part of the memorandum concerns a paraphrase of his evocation in the preceding chapter of the Doctor's disagreeable method of education; the rest gives a very brief account of the subject:

These young gentlemen, out walking, very dismally and formally (observe it's a very expensive school). . . . I think Doctor Blimber, a little removed from the rest, should bring up the rear, or lead the van, with Paul, who is much the youngest of the party. I extract the description of the Doctor. Paul as last described, but a twelvemonth older. No collar or neckerchief for him, of course. I would make the next youngest boy about three or four years older than be [N, 1: 824-25]

Phiz deviates from the instructions and text by including seventeen rather than the ten boys said to be in the establishment at one time, and the only possible excuse for this might be that the smaller number would populate the design too sparsely; in the drawing (Elkins) six are lightly drawn, suggesting a late addition. Besides making this influence.

The remaining three subjects in the first six monthly parts are devoted to the aftermath of Paul's death: the first, "Profound Cogitations of Captain Cuttle" (ch. 15), contrasts with Paul's farewell in foreshadowing Walter's actual sea journey, while "Poor Paul's Friend" (ch. 18) and "The Wooden Midshipman on the look out" (ch. 19) deal with Florence who turns away from her father after Paul's death.

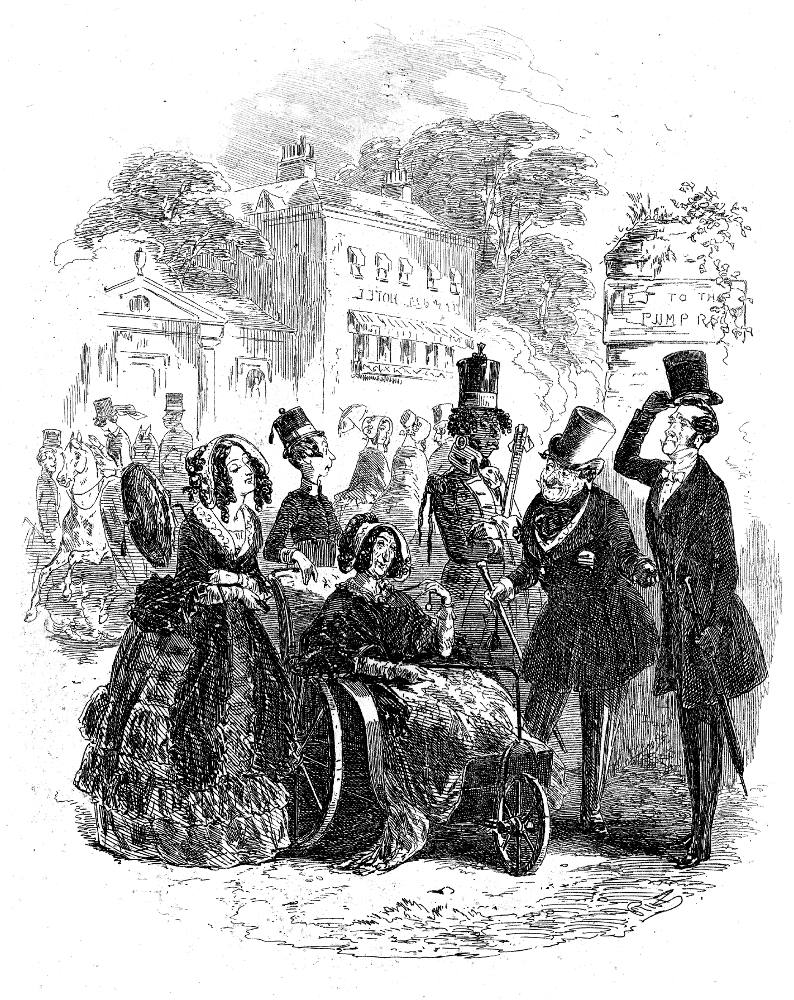

Preliminary study and published plate: Major Bagstock is delighted to have that opportunity illustrations 62 and 63]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

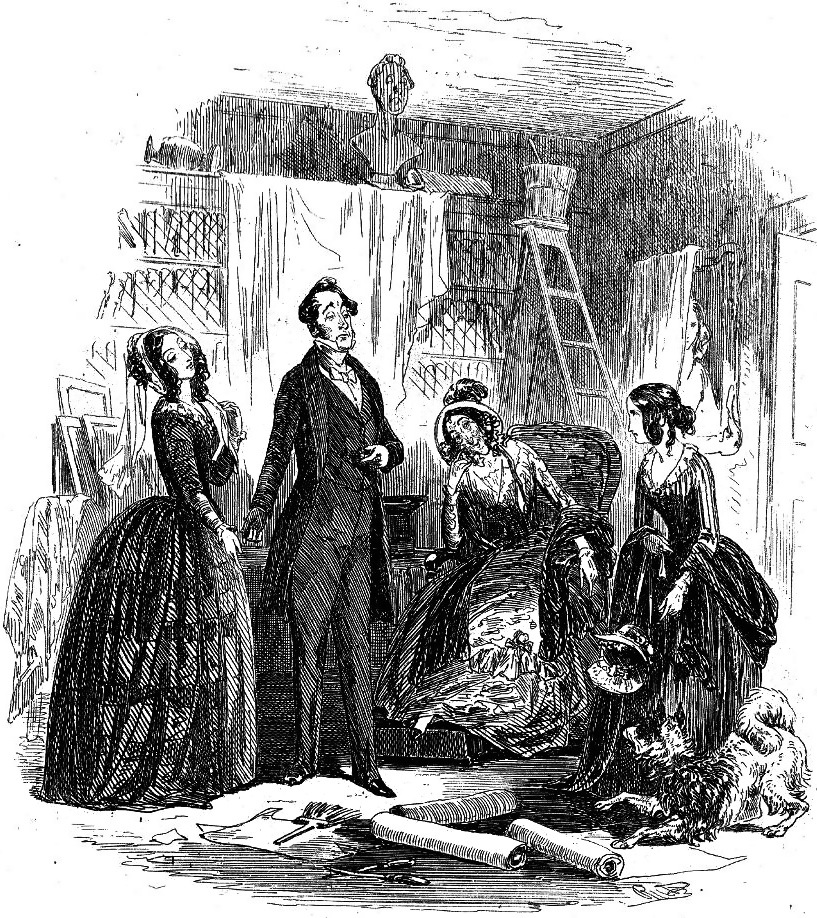

Despite the number of child subjects in the first twelve illustrations, taken as a group these etchings bring out strikingly that Dombey and Son is populated by a large number of monstrous or dangerous women, and that sexual hatred and frustration lurk not far below the surface. Though it is centered upon the Toodle family, the very first plate features both Miss Tox and Mrs. Chick who preside over the scene like a couple of harpies. In the third plate, Susan Nipper, Miss Tox, and Mrs. Chick again chill the atmosphere, and the spiritually castrated Mr. Chick looks like a guilty schoolboy trying to control his urge to whistle. In "Paul and Mrs. Pipchin" we have the famous witchlike widow, a "disappointed" woman who hastens Paul's decline. But the themes of sexual conflict and female domination begin in full with "Major Bagstock is delighted to have that opportunity" (ch. 21).

The Major introduces Dombey to Mrs. Skewton and her daughter Edith Granger at Leamington Spa in a plate which is special if only because two sets of instructions from Dickens survive, the second a comment on the illustration preliminary [92/93] sketch; two drawings survive as well. As is generally the case with the later Dombey and Son plates, apparently Browne was given no text to work from (by his own account, Dickens had not yet written the text). Thus in a sense the instructions are a kind of ur-text. Dickens wants "to make the Major, who is the incarnation of selfishness and small revenge, a kind of comic Mephistopbilean power in the book," and he proceeds to describe each of the figures' personalities, but little of their appearance. In outlining the subject, Dickens says nothing about arrangement of figures, and even gives Browne the choice of portraying them in "the street or in a green lane ... if you like it better" (N, 1: 17-19).

Evidently the first lengthy set of instructions was inadequate to convey Dickens' inner vision, for he returned Browne's preliminary sketch with polite but firm directions to dress the Native "in European costume:' and to "make the Major older, and with a larger face." (This may be the Dexter sketch, reproduced in plate 26 of the Victoria and Albert Museum catalogue, although both Dombey and the Native (who may have been erased) are missing.)As he was to do with several of the plates involving Dombey, Edith, and Carker, Browne made this very much his own creation by adding details which are not merely incidental. The tableau of characters — Edith, Withers the page, Mrs. Skewton, the Native, Bagstock, and Dombey — is ordinary enough in arrangement, though there is a greater power of portraiture evident in the uncaricatured figures of Edith and Dombey than would have been true a few years earlier, and the grotesques are fine indeed. But Browne has added two groups of characters not requested by Dickens in either memorandum. Between Withers and the Native, in the background, are two women and a man, walking toward the distance; the woman on the left, like Edith, wears a bonnet and carries a parasol, and is looking back at her in a way that implies curiosity and perhaps disapproval.

Preliminary study and published plate: Mr. Carker in his hour of triumph illustrations 71 and 72]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

This woman may be no more than a visual parallel to Edith, but at the far left of the etching another group serves a more functional purpose: a man raises his hat to a woman on horseback (as does Mr. Dombey to Edith and her mother on the opposite side) who looks down at him; she is followed by a liveried servant. This group works like one of Phiz's typical background emblems, providing implicit commentary on what is taking place in the foreground. The woman is in a dominant position, above one subservient male and ahead of another, and if I am correct in [93/94] thinking that she wears a hunting costume, then Dickens' remark about Edith — that she "flies at none but high game" — has been given direct visual expression. There is also a foreshadowing of "Mr. Carker in his hour of triumph," in which Edith has humiliated Carker, and a statuette of an amazon on horseback strikes down a male warrior. Since much of the novel is devoted to Dombey's attempt to crush his second wife's spirit, our sympathies do tend to rest with Edith, but this illustration (along with subsequent plates) helps to state the theme of male-female conflict, with the woman a match for the man. The working drawing for this plate (Elkins), which Dickens in his second letter told Browne he did not need to see, contains nearly all the details of the etching, but the Native is little more than a blur, having obviously been erased. However, a careful perusal reveals that Browne has, without drawing the lines in, used his blunt point to transfer the final version of the Native to the etching ground.

The plate with which this one is paired, "Mr. Toots becomes particular — Diogenes also" (ch. 22), forms a comic counterpoint. As Mr. Dombey is about to woo Edith with the purely ulterior motives of possessing a wife and producing another male heir, so Toots is trying to kiss Susan Nipper in order to get closer to her mistress, Florence. Susan herself is by now transformed from "Spitfire" into a loyal companion for Florence, and in these illustrations she is much prettier than in earlier plates. Ultimately she is the comic, virtuous avatar of the strong-minded woman, transforming Toots's romantic love for the unattainable Florence into a sensible affection for herself. Dickens was perhaps not fully aware of the extent to which sexual conflict developed as a major concern in the novel; but Phiz's plates establish the theme as integral. This plate also offers a useful example of how ephemeral the emblematic details could be to the man who did the final biting of the lines into the steel plate, for surely the inclusion of both a thermometer and a barometer on the wall was supposed to represent the rising heat of the situation, and Miss Nipper's stormy temperament (in his later, extra portrait, Phiz included a picture of an erupting volcano and a box marked "Lucifers" to symbolize this temperament); however, neither steel clearly indicates that the thermometer is high, or the barometer falling, as we might expect, although the barometer's needle is in the same position as in the fifth plate of David Copperfield, where it is clearly marked "stormy".

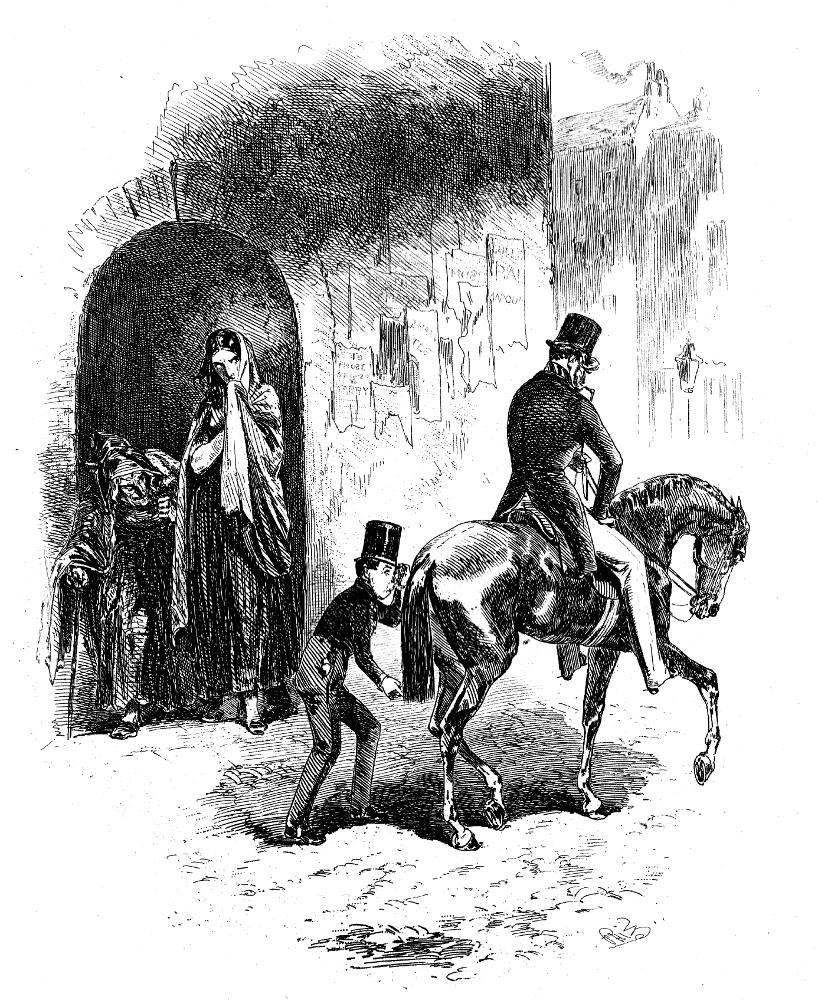

From Part VIII to Part X, a further sequence of five plates develops the theme of sexual conflict along the Dombey-Edith-Carker axis of the novel. In "Mr. Carker introduces him [94/95] self to Florence and the Skettles family" (ch. 24), the novel's most sinister villain shows his teeth to Florence and, graphically, to us for the first time. Browne could never have incorporated most of the text's details into his illustration: Carker whispering to Florence that Walter's ship has not been heard of yet (and the insinuation that Carker is thinking about Florence as a possible wife for himself) and the unspoken communication between them about Florence's complex feelings toward her father, whom she loves but knows would not be pleased to hear from her. Instead, Browne stresses general things about Mr. Dombey's confidential agent not mentioned explicitly in chapter 24. Carker holds a close rein on his horse so that the animal is totally dominated, as Carker will dominate both Dombey and Edith. Carker's nastiness is also alluded to comically. In chapter 22, Dickens had referred to the naturalness of Diogenes' antagonism to Carker: "You have a good scent, Di, — cats, boy, cats!" (p. 224). In the etching, the natural world's instinctive reaction to Carker's evil slyness is brought out not only by the little dog running toward him, but also by the ducks flying away and the donkey raising his ears in terror. The geese, with their upright necks, also parody the dreadfully snobbish and stiff-necked Skettleses in this illustration. In the companion etching, "Solemn reference is made to Mr. Bunsby" (ch. 23), Florence is almost an exact mirror-image of herself, even linking her arm in someone else's in both plates; in both she also listens to a man speak of Walter's fate at sea.

The next two monthly numbers and their illustrations deal largely with the progress and fruition of Mr. Dombey's courtship, and Phiz achieves some of his most telling effects. In "Joe B is sly Sir; devilish sly" (ch, 26), Carker observes Dombey with the same concentration he has devoted to Florence, but here the one observed is unconscious of the observer. It is one among many plates in which looking-at and spying-upon are central motifs, usually with Dombey as the unconscious cynosure of many hostile eyes and thoughts. From his reading of the text or his understanding of the general account Dickens may have given him of the situation, Phiz has seen fit to include a painting on the wall of the "wooing" of Uncle Toby and the Widow Wadman in Tristram Shandy, almost certainly derived from C. R. Leslie's painting of this subject, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum — a similarity noted by T. W. Hill. The application is clear, and startling: the joke around which the courtship in Sterne's novel revolves is that the Widow wants to make sure Toby's war wound is not such as to incapacitate him [95/96] sexually, but Toby is incapable of understanding her hints. Phiz perhaps does not mean to question Dombey's virility, but the notion of sexual incapacity becomes entirely apposite when one realizes that Dombey is not able to command Edith's submission, that his wish for an heir is never fulfilled, and that he is — in appearance at least — cuckolded by Carker (and up to nearly the last minute Dickens intended a literal cuckolding).

Left: Mr. Dombey introduces his daughter Florence illustration 64] Right: Portrait of Miss Skewton illustration 65].

The companion plate, in which matters have progressed further, "Mr. Dombey introduces his daughter Florence" (ch. 28) is notable for the skill with which Phiz has delineated the characters without a touch of caricature except in the case of Mrs. Skewton, who is, after all, caricatured in the text. Browne directs no emblematic ammunition against her here, but in 1848, as one of a set of eight "extra" portrait illustrations to Dombey and Son — one group of eight etchings, and another of four engravings, were published separately after the novel's completion — he depicts her in much the same pose, but in more detail, as a pathetic grotesque with one scrawny, stockinged foot emerging from beneath her skirts, a bonnet with wilted flowers, and a thin hand toying with a heart locket. On the floor is a magazine open to "La Mode," and on the couch a book, The Loves of Angels, which has an ambiguous meaning to say the least — is Mrs. Skewton "angelic" in her sweetness or her deathliness? The vase of flowers nder glass suggests the extreme care necessary to keep her looking more alive than dead, while the cupid decorating the mirror regards her archly, as though to say, "You'd better not look in here, my dear." (The motif of the looking glass ominously predicting a woman's death is sketched several times in Browne's 1853 notebook.) At the very top of the composition is a Watteau-like pastoral scene of men and women in seventeenth-century dress, and immediately over the old lady's head, a clock with Father Time in a most threatening pose looks down upon his nearly conquered victim.

I mention here an illustration executed after the novel was first published because it provides some additional evidence that Browne could take the trouble to interpret Dickens independently of the author's monthly instructions — and that he had the skill and understanding to do so. In the remainder of the Dombey plate in question, Browne includes two details which relate to characters other than Mrs. Skewton: the nearly covered portrait of Dombey's late wife continues the motif of eyes secretly observing Dombey, for she appears to peek out from behind the [96/97] cloth. Further, Browne here makes the dog, Diogenes, explicitly hostile to Dombey, whereas in the text he is merely lively because he is happy to see Florence — a change which suggests the underlying alienation between Florence and her father.

Left: Coming Home from Church illustration 66] Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

The sequel plate in the next part, "Coming Home from Church" (ch. 31), Browne's first for Dickens to be printed horizontally, is a triumphant culmination of what is best in his work up to this time. It is also an especially important example of the integration — even the inseparability — of text and illustration. Dr. Harvey has praised this plate, citing in particular the emphasis upon Dombey's separation from the crowd and his inferiority to it in "vitality and character," as well as the telling details of the Punch and Judy show, which is in the text, and the funeral procession going in the opposite direction, which is not (Harvey, p. 141.). The crowd is more than simply vital, however, for the people immediately near the portico look at Dombey with amusement as well as something vaguely menacing, and the image of Dombey in earlier plates as the unaware object of prying, knowing eyes is further advanced.

One of these figures clarifies what is otherwise an obscure passage in the text, at the end of the paragraph being illustrated:

And why does Mr. Carker, passing through the people to the hall-door, think of the old woman who called to him in the grove that morning? Or why does Florence, as she passes, think, with a tremble, of her childhood, when she was lost, and of the visage of good Mrs. Brown? [ch. 31, p. 316]

Two curious questions, intelligible as soon as we look at the etching and notice that "good Mrs. Brown" is seated just to the right of the portico. Carker and Florence must have experienced a subliminal impression of the old harridan when they passed through the doorway. It is most likely that Dickens had instructed Browne — who had yet to portray her — to include this figure; we do not even learn that "Mrs. Brown" and the old woman in the wood are one and the same until later. The perfection with which picture and text are integrated here is indicated by the fact that the passage quoted above seems not to have bothered generations of Dickens readers, and the presence of good Mrs. Brown was not remarked in print until my 1969 article in English Language Notes. T. W. [97/98] Hill says this plate is "almost all Phiz's creation" (51), and one would like to credit Browne at least with the funeral procession which is the same kind of spatial parallel as the background details of the plate depicting the Leamington introduction, and the same kind of conceptual analogy we find in a later plate, "Another wedding," which I believe comments satirically on this one.

Preliminary study and published plate: The Midshipman is boarded by the enemy illustrations 67 and 68].

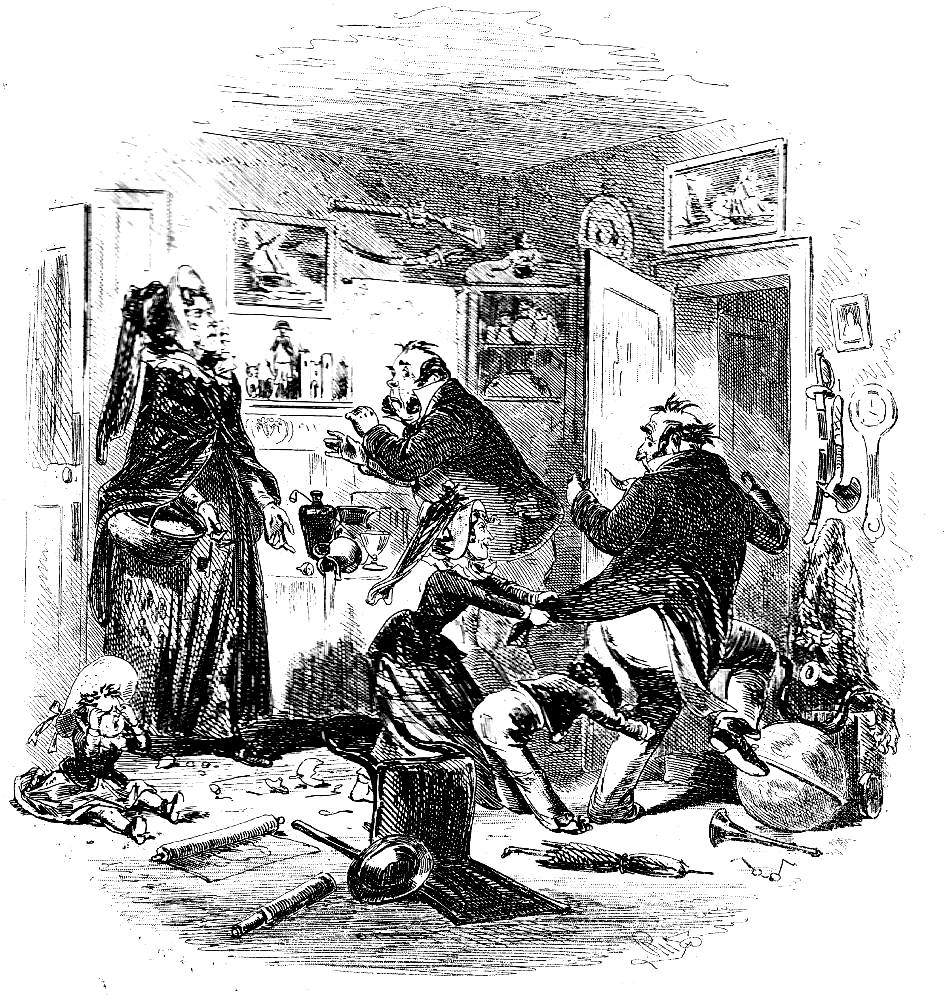

The first such parodying occurs, however, in the comic plate, "The Midshipman is boarded by the enemy" (ch. 39), in which the Bunsby-Mac Stinger story echoes certain aspects of Edith and Dombey's situation. The predatory women and the "forced" marriages are paralleled; Browne offers considerable iconography both to illustrate this theme and to tie the two couples together. There are, for example, prints of a sea-battle and a foundering ship, an overturned globe, the upset vestiges of such masculine activities as smoking and drinking, and what is apparently the skin of a huge predatory bird with frightening talons. But further, when we recognize that Mrs. MacStinger holds nearly the same position and strikes the same pose as Edith in the companion plate (discussed below), we realize that the tiny Medusa head near Mrs. MacStinger and the caption, "Medusa" (on Steel 25A only) make up a fitting emblem for both women — for do not both reduce men to powerlessness by a mere look.

There are two extant drawings for this plate. Both are reversed and in pencil, but the less finished one (Elkins) does not contain the "Medusa" inscription, and Captain Cuttle's hook is on the wrong hand, though there is clear evidence that this drawing was the one used in transferring the design to the steel, including indentation on the misplaced hook. The other drawing (DH) is very finished, with each detail nearly identical to the etching: the "Medusa" is included, and the hook is on the proper hand, although the tiny head of Medusa is not evident. It seems likely that this drawing was used as a guide to the details of the etching, as I have suggested is the case with two of the drawings for Martin Chuzzlewit.

Dickens himself refers to Edith as Medusa during her interview with Florence, just before the great showdown with Dombey: "She did not lay her head down now, and weep, and say that she had no hope but in Florence. She held it up as if she were a beautiful Medusa looking on him, face to face, to strike him dead" (ch. 47, p. 462). The influence here could well have been one of the artist upon the author, for this passage occurs in an installment two months after the plate in question. Browne's "Medusa" conceivably could refer to Géricault's famous painting, The Raft of the Medusa, which would at least explain the linking of this title with a sea scene, although the picture looks more like a ship than a raft. The theme of cannibalism associated with the Medusa's shipwrecked passengers is even relevant to the predatory world of Dombey and Son.

The effect of such parallels between comic and serious plates is not so much to ridicule the more serious elements in the novel as to help unify the narrative structure by stressing the theme of sexual conflict. To view "A chance Meeting" (ch. 40) alongside its companion is to receive sudden enlightenment. Dickens has already been making great play with parallels in juxtaposing the stories of Edith and Alice. Browne's illustrations extend the parallels further, beyond the emphasis upon high-life and lowlife prostitution to a vision of the terrifying power of woman. To [98/99] put the matter another way: through the parallel between Alice and Edith, Dickens expresses his social vision of the cash-nexus between human beings, but through the illustrations Browne stresses the underlying view of woman as a potentially destructive force. Edith and Alice in "A chance Meeting" are drawn with so little attention to scale that they appear to be giantesses; but this serves to emphasize the almost mythic power of women. And the parallel of Edith and Mrs. MacStinger, implied in their similar positions, further promotes this theme. One could argue that Phiz is equally justified in neglecting scale in "Florence parts from a very old friend" (ch. 44), making Mrs. Pipchin another giantess, for she too is one of the monstrously powerful women in the book, both child-queller and (it is implied) husband-queller, halfway between the serious and the purely comic figures in conception.

The first in a series of plates depicting the course of Dombey's, Edith's, and Carker's headlong flights to self-destruction, "Mr. Dombey and his 'confidential agent"' (ch. 42), is of special interest for the care with which Browne sets forth visually the drift of Dickens' text. Carker regards covertly the painting on the wall which happens to resemble Edith; but Browne has added another painting depicting a seminude woman at her outdoor bath. A close look (particularly at Steel B) reveals at left the head of a man who is evidently watching the bathing woman; the most likely allusion is to Actaeon coming upon Diana at her bath. (Phiz used this allusion twice, with more graphic clarity but less emblematic significance, in Lever's The Daltons.) That Actaeon was torn to pieces by his own hounds as a consequence of his spying may allude to Carker's ultimate self-destruction resulting from his interference in Edith's life. Another apparent contribution of Browne's is the small dog near Carker's feet; since it is a lapdog, looking up at Dombey with its tongue out, it seems to function as an emblem of Carker himself, fawning upon his master; consistent with this emblem, Carker's teeth are here concealed, while in all previous plates they are very much in evidence.

Abstraction and recognition illustration 69]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

Browne's emblematic imagination seems to have been stirred by the theme of sexual conflict, for in the next pair of plates he displays not only his skill as an etcher, but his ability to make use [99/100] of melodramatic conventions to good effect. In "Abstraction & Recognition " (ch. 46), the statuesque figure of Alice Marwood stands in the dark gateway, but the highlights and the aura of light about her head make her the dominant figure; her mother, though witchlike and sinister, is under Alice's sway, and she blends and recedes into the shadows. The most interesting compositional achievement is the way Browne balances the "abstracted" Carker and Rob against the "recognizing" Alice and her mother, leaving space between the former lovers in the center of the etching for a collection of significant posters on the. wall. Phiz has come some distance in making such details credible, for these posters look like a random and tattered group, blending with the street scene and the ragged poverty of mother and daughter.

As with all the Dombey plates there are two steels, and in them the posters vary slightly. The source of such variations may he inferred from the extant drawings: a sketch (Gimbel) facing the same way as the final etching but containing most of the poster inscriptions, and the reversed working drawing (Elkins), in which these inscriptions are absent. There is also an early proof (Gimbel) in which the words are again absent, indicating that they may have been etched in reverse directly onto the steel at a late stage. The more obvious posters read "Observe" (Steel B only), alluding to the immediate subject of the plate; "Bal Masque," suggesting Alice's concealment; "Cruikshank/Bottle," in reference to the Hogarthian set of eight plates published in 1847, depicting the fall of a family, through drink, into poverty. The others are rather more complex. "Down Again / 6" (Steel B only) is, literally, a merchant's announcement of a drop in prices, but here it foreshadows the fall of Carker, who will be brought down thanks to Alice's vengeful scheming. "To Those About to Marry" would now undoubtedly carry the implied injunction, "Don't," but has a more somber overtone in this novel than in its earlier use in Martin Chuzzlewit. "Moses" would be the famous clothing merchant, who wrote poetical advertisements and took advertising space in the third part of Dombey and Son; but in the immediate context it probably has a broader meaning as well: with Edith about to run off with Carker, it evokes the Commandments against adultery and coveting one's neighbor's wife. [100/101]

The remaining poster, "Theatre/City/Madam," is the most interesting allusion in the group. Massinger's The City Madam was produced in London as recently as 1844 (see Nicoll, 4: 442), and it contains enough similarities to Dombey to make inescapable the conclusion that it is the source for certain elements most relevant to the present illustration. A wealthy City merchant, Sir John Frugal, whose lack of a male heir is "a great pity," has a wife, who, like Mrs. Skewton, pretends to be younger than she is. Sir John also treats his younger brother Luke much as James Carker treats John: Luke has squandered the large fortune left to him, and his debts have been paid by his brother, who employs him, treats him like a servant, and reminds him of his disgrace. Luke embezzles money and urges the other clerks to emulate him, and like John Carker speaks of himself as an "example"; but unlike John he turns out to be a total scoundrel. In addition, a bawd, Secret, is reproached by her prostituted daughter, Shave'em, for not caring "upon what desperate service you employ me, / Nor with whom, so you have your fee" (act 1, scene 1, lines 11-12). The parallel with Alice and her mother is clear, and since it seems unlikely that so many parallels could have been coincidental, it is probable that Dickens either consciously drew upon Massinger's play, or, at the very least, that he or Phiz recognized its relevance. As well as giving us an insight into Dickens' knowledge of Jacobean drama (and remember that he refers to the final situation between Carker and Edith as an "inverted Maid's Tragedy"), (Letter to Forster of 21 December 1847 — N, 2: 63.) this illustration shows at how fundamental a level picture and text could complement one another.

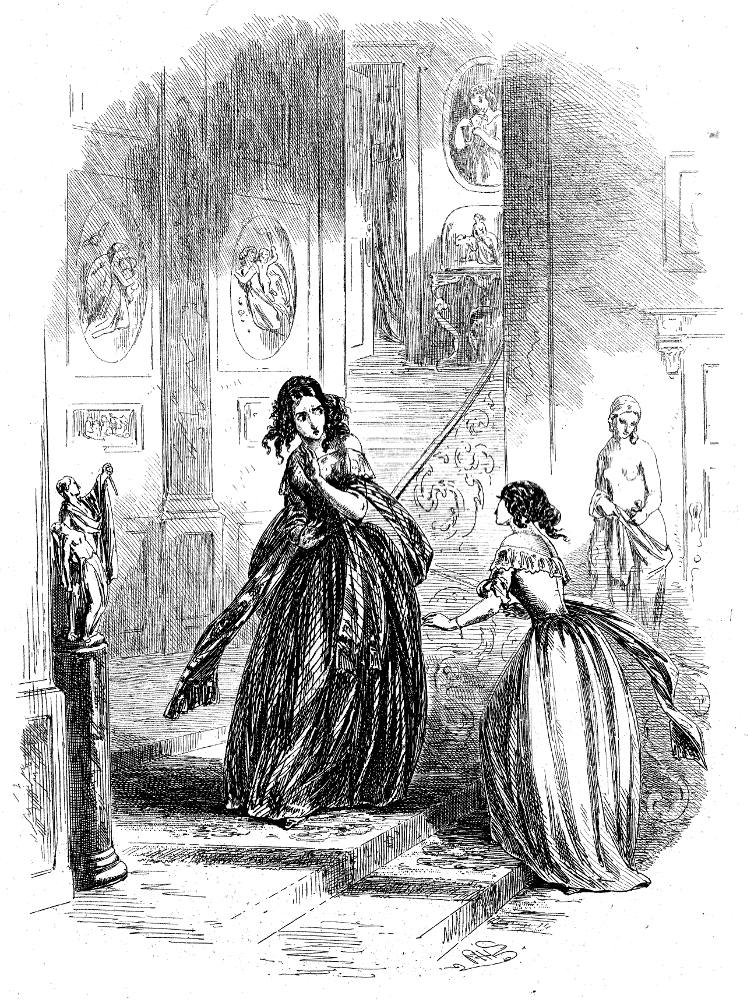

Florence and Edith on the staircase illustration 70]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

The relation of "Abstraction & Recognition" to its companion, "Florence & Edith on the Staircase" (ch. 47), is primarily sequential, rather than formal, in that Edith's flight follows from Carker's plans made during his "abstraction"; but the pairing implies a link between Alice and Edith as each raises her left hand to her mouth. Again, Browne has posed his characters theatrically without falling into absurdity. But in this plate perhaps more than in any other, full significance of the illustration is conveyed by the emblematic details taken together. The position of the topmost detail, an oval painting of a young woman holding a dove at her bosom, suggests a guiding principle for reading the plate. Browne's use of a similar image in later years is probably reliable evidence of its meaning here. At some point [101/102] before 1859 (when he moved away), the Croydon Board of Health asked him to design a new seal for them. He first submitted a full-length drawing of a young woman holding a dove much as in the detail for the staircase plate; it bears the caption "Purity," and beneath, "Sans Tache." (Thomson, p. 223; reproduced on p. 221.) The placement of an emblem representing spotless purity at the very top of the present etching implies a hierarchy of values, and Browne's device conveys not only purity, through the dove, but spiritual love, since the bird is succored at the girl's breast.

In the lower half of the design we find two pieces of statuary flanking Edith and Florence that respectively refer to Dombey's treatment of Florence and to Edith's conduct and the situation she has become enmeshed in. The left-hand statue depicts a man about to sacrifice a young woman with his knife; the probable allusion is to Agamemnon and Iphigenia, a father sacrificing his daughter to what he thinks are higher principles. The other statue represents Venus holding the apple she had been awarded by Paris, and the implications are bitterly ironic: it is Carker who is Paris in the novel, choosing Edith over the other two women he has favored in the past, Alice Marwood and — as we are liable to forget — Florence Dombey. Above Edith, the wall plaques are Thorwaldsen's popular reliefs, "Night" and "Morning," both of which show children borne aloft by maternal angels; they evoke the twice-thwarted motherhood of Edith. The remaining emblem is a figurine directly below the emblem of Purity depicting a woman riding on a quadruped which to all appearances might be a bear or some member of the cat family. T. W. Hill, without any explanation, says this is "Una and her lion" a reference to The Faerie Queene; the assumption is reasonable, since Una (Truth) would consort very well with an image of Purity. Part XIV of Dombey and Son included, among other advertisements, a page by Felix Summerly's Art Manufacturers which refers to "PURITY, OR UNA AND THE LION, a Statuette. Designed and modelled by John Bell." However, the reference continues that the statuette is "a companion to Dannecker's Ariadne, or Voluptuousness;" and it is to this second sculpture that Phiz's detail in fact bears its strongest resemblance. The motif is that of Ariadne on her panther, and to carry out the allusion produces interesting results: Dombey would be Theseus, who deserted Ariadne, while Carker is Dionysus, arriving [102/103] on his panthers to abduct her. The ironies are considerable, however, since it is Edith who, physically at least, abandons Dombey, and Carker's function as a Dionysus is largely in his own "voluptuous" mind rather than in Edith's response to him.

But how successful is the plate as an illustration? To modern sensibilities the message of the emblematic details may be painfully labored, even if the implications of Venus and Ariadne are far from simple; yet one should consider how such an illustration might function in a novel read as a serial over a period of nineteen months. In addition to enhancing continuity through the repeated depiction of central characters, such illustrations could underline moral and psychological themes upon which the novelist might otherwise feel obliged to expatiate at length. Dickens' and Browne's collaboration in such matters seems to have been at least partially intuitive. Sometimes the collaboration would work and sometimes not, but its function was more important to a long, somewhat sprawling novel in parts than to a more tightly organized work half the length or less, such as A Tale of Two Cities — in which Browne does not employ a single emblem — or Hard Times and Great Expectations, which have no illustrations.

The next plate to continue the Dombey-Edith-Carker triangle, "Mr. Dombey and the World" (ch. 51), pleased Dickens, (N, 2: 63.) and is another example of how picture and text may be closely integrated. The "stare of the pictures," and of Pitt's bust, as well as the eyes in the world's "own map, hanging on the wall," all derive from Dickens' text. Among the pictures that Phiz has included are the portrait of the first Mrs. Dombey, once again peering out from behind a cloth, and a staring miniature of little Paul; he has also introduced an especially sardonic and satyr-like Father Time immediately behind Dombey's back (perhaps a reference to Dombey's failure to control time in the case of Paul), an amused face on the urn next to Mr. Pitt, and, upon the fire place, two heads and a naked woman (or a Sphinx?) also regard Dombey. The reminders of Paul and Time imply something more than the shame of cuckoldry, but the withered and drooping flowers are suggestions of sexual impotence, while the Major's way of gesturing with his stick seems aggressively phallic in contrast to Dombey's present languidness. The peacock feathers attached to the mirror — again, hanging down, instead of [103/104] displayed correctly — have three appropriate emblematic meanings: they are another example of "eyes" looking at Dombey, they inevitably evoke the idea of Dombey's overweening pride, and they symbolize the misfortune which has come to the House of Dombey.

We continue the progress of Edith, and particularly of Carker and Dombey, through to their conclusions in three more plates, those for Parts XVII and XVIII, and one (not including the summarizing frontispiece) in the last, double part. "Secret intelligence" (ch. 52) shows Dombey eavesdropping as Mrs. Brown wheedles from Rob the Grinder the whereabouts of the eloped pair, while Alice stares at Dombey with an expression of suppressed hatred. The hovel is effectively drawn and Mrs, Brown's cat hints at her witchlikeness, but one may feel that the shading is scratchier than usual and that served in this novel for Carker's the dark plate technique, reflight, would have been more effective. One subtle set of details, surely of Phiz's invention, is the bowl of vegetables, the paring knife, and parings on the floor; their sole purpose is to serve as a metaphor for the process of peeling off Rob's resistance layer by layer, until the core of truth is revealed.

Preliminary study and published plate: Mr. Carker in his hour of triumph [illustrations 71 and 72].

The companion, "Mr. Carker in his hour of triumph" (ch. 54), has been given considerable if incomplete attention by critics (see Mrs. Leavis, p. 356, and John R. Reed). On a general level the etching is a suitable partner for the preceding plate in direct visual parallelism (both men on the far left, both women on the right) and the inverted thematic parallelism of Dombey-Alice and Carker-Edith, each woman having used her partner in the illustration as a despised means of destroying the man with whom she has been linked. Mrs. Leavis points out that the melodramatic poses of Carker and Edith fully suit the high-flown rhetoric of the text, but it should be said that in comparison with the working drawing, Edith's figure and expression resemble a stuffed dummy's — which — indicates that translation from drawing to etching is not always perfect. But a number of other elements make this a most important illustration.

However dubious at first may seem the suggestion by John R. Reed that Edith's gesture toward Carker's groin is castrative, the emblematic details in this plate do in fact emphasize her destructive tendencies — and perhaps those of women in general, [104/105] specifically in connection with their sexual allure. In the first plate of Hogarth's Marriage A-la-Mode, one of the paintings belonging to the Earl who is arranging his son's marriage portrays Judith just after she has killed Holofernes. although the large picture (larger than most of Phiz's emblematic details) behind Edith of Judith and Holofernes does not resemble this one, another, at right angles to it and barely distinguishable because of the reflected candlelight, shows a Judith in very much the pose of Hogarth's; there is an even greater resemblance between the large picture behind Edith and the frontispiece Hogarth did for William Huggins' oratorio, Judith — the outstretched left hand of the figure in that frontispiece is echoed by Edith herself. It is as though Phiz wished to make sure that we noticed the parallel between Edith and Judith.

As Dr. Reed has noted, both the sword of Judith and the spear of the amazon point at Edith's head, and may suggest Edith's self-destructiveness. If one is hesitant to attribute such an insight to Phiz, one can imagine that Dickens said something to his illustrator about Edith's ruinous course and Browne interpreted this accordingly. For the amazon herself Browne in fact drew upon his own stock of graphic ideas, the statuette closely resembling a detail in an illustration to G. P. R. James's The Commissioner (1841-43), where it comically represents the housemaids who have in a "Revolt of the Petticoats" set upon the men who insisted that their boxes be searched. But this does not exhast Phiz's invention. On the chimney piece there are ceramic figures of courtiers and ladies (two pair, ironically suggesting the two couples, Edith-Dombey and Alice-Carker), and a curious clock at the bottom of which the figures of a reclining Venus and Cupid are discernible, while from the timepiece above an unclear figure hovers rather ominously. There is possibly no precise allegory intended here, but the notion of Time suspended over Beauty and Love seems appropriate, if not brilliant. One may also interpret the two mirrors, both facing Edith, as symbols which imply that she is fully recognizing what she herself is, in the process of spurning Carker.

Following directly from Edith's Judithean confrontation with Carker — interrupted by Dombey's arrival — is the flight of Carker in "On the dark Road" (ch. 55). It is an impressive composition, [105/106] brilliantly catching the motion of the carriage, with a line of trees receding off into the vanishing point at right resembling a column of men implacably following the fugitive. The solitary cross marking a lonely grave forecasts Carker's impending death; no such detail is mentioned in the text where it would be intrusive, but in the etching it forms a natural part of the whole scene. Its unobtrusiveness is aided by the new "dark plate" technique, which increases greatly the possibilities for tonal variation — especially, but by no means exclusively, in scenes of darkness and thus a sense of space. although this is often cited as Browne's first dark plate, in fact the first seems to have been the frontispiece to the 1847 edition of Harrison Ainsworth's Old St. Paul's (Part XVIII of Dombey and Son having appeared in March 1848), which, along with a title page vignette, was added to the John Franklin illustrations of the 1841 first edition. Franklin's etchings were nearly all done with this technique, which may well have inspired Browne to adopt it though with differing effect.

The dark plate becomes ubiquitous among Browne's etchings in the late forties and through the fifties, and it is as well to explain the technique at this point. In its most basic form it provides a way of adding mechanically ruled, very closely spaced lines to the steel in order to produce a "tint," a grayish shading of the plate. It is this simple method that Browne occasionally used for authors other than Dickens. But in general he made more subtle and complex use of the dark plate. Some of the proofs in the Dexter Collection show the outline of the general subject bitten in without the tint, and the process would thus have been something like this: the subject was etched through the ground in the usual way, then the plate bitten, the ground removed, and proofs taken. The lines already fully bitten in the steel would be packed to prevent further biting, and the steel again covered with a (transparent) ground. A ruling machine, adjustable for distance between the lines, would then be drawn over the ground, cutting through it and exposing the steel below; this might be done only horizontally, or diagonally as well, or in two opposing diagonals, so as to produce tiny lozenges. Further shading by means of etching needle and roulette would also be done at this stage (Despite the fact that the pre-tint proofs are in the Dexter Collection upon which they base most of their findings, Thomas Hatton and Arthur R. Cleaver state that the steel was tinted first (p. 276), but they are clearly wrong, and a surviving proof (Dexter) of the thirty-ninth plate of Nicholas Nickleby further confirms the point, since its mechanical tint must have been ruled after the rest of the design was etched. Yet the same technical misunderstanding is still subscribed to by Alan Horsinan, in the Clarendon edition of Dombey, p. 871.). The highlights, areas which were to remain white, would be stopped out with varnish, and then the biting could commence. [106/107] Those areas which were to be lightest in tint would be stopped out after a short bite, the next lightest after a longer bite, and so on down to the very blackest areas — which would never, except where wholly exposed by the needle, become totally black, but would shimmer with the tiny lights of the unexposed bits between the ruled lines; the darkest sky in "On the dark Road" has these little lights, while the dark parts of the puddle have none, apparently having been exposed to the acid by the needle rather than the ruling machine.

It is breathtaking to consider how much time and effort must have gone into the production of such steels, and no doubt Robert Young deserves some of the credit for the effectiveness of the dark plates. Those by Franklin for Old St. Paul's may at first strike one as more finely done: Franklin uses more closely spaced lines, resulting in an almost velvety texture of grays and blacks, but he never makes the kind of dramatic use of the method that Browne does, and thus by contrast Browne appears a bold experimenter. Strangely, the technique does not seem to have been widely used by illustrators, and manuals of etching of the period scarcely ever mention the ruling machine as an available aid. I suspect the technique was just too much trouble for commercial illustrators, and yet too mechanical for those etchers with pretensions to high art.

Carker's actual death is reserved for the allegorical context of the frontispiece, and we are left with two more plates which bear significantly on the Edith-Dombey-Carker situation and the theme of unhappy marriage and female predation. "Let him remember it in that room, years to come" (ch. 59) depicts the moment before Florence's reconciliation with her father, but in a way it illustrates much more; it is probably not accidental that the particular passage in which Florence comes into the room occurs not at page 595, where the illustration is placed in the first bound edition, but four pages later. In between, the text dwells upon Dombey's thoughts, centered around the sentence which forms the plate's title, and brings him almost to the point of suicide just as Florence enters. The details of the illustration emblematically encompass much of this extended indirect monologue. Society (including the worldly Major), which has abandoned Dombey, is represented in the rolled up map of the [107/108] world and the disapproving bust of Mr. Pitt. The screen shows three images which contrast with Dombey's condition: children at play, a pastoral scene of a young man playing the flute to a young woman, and a rather undefined scene outside a church, possibly a wedding. If the latter is correct, the three panels embody the sequence of a happy boy-girl relationship from childhood through courtship and marriage. The candle on Dombey's dressing table, nearly burnt down, is a traditional image suggesting Dombey's approaching death. In this context, Florence's appearance with sunlight behind her perhaps should not be taken quite literally, for it gives one the impression that she is a visionary apparition rather than a real person. And so it must strike anyone reading the novel for the first time in a bound volume (assuming the illustration is placed as in the original bound edition), since such a reader will not know for four pages whether Florence actually appears or this is her ghostly image.

Another wedding [illustration 73]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

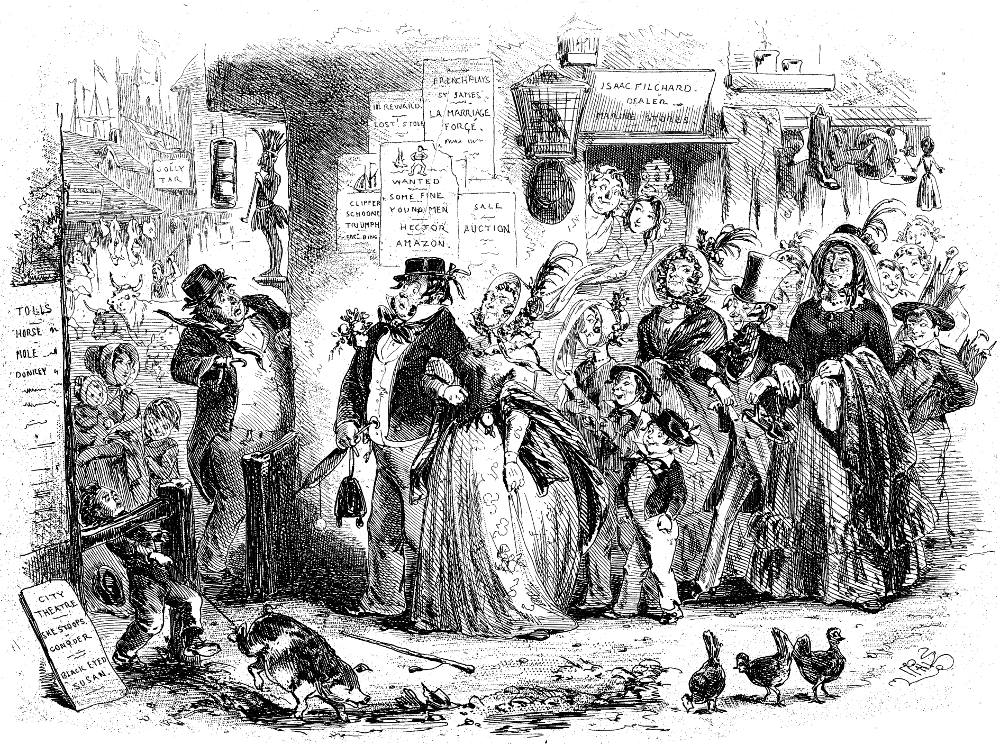

The companion plate, and the last to depict an actual scene in the novel, relates visually and conceptually back to an earlier plate, Coming home from Church, by treating marriage comically and ironically as a trap set by predatory women. Although the adjective in its title, Another wedding (ch. 60), is intended to refer to the recent marriages of Florence and Susan, the depiction of the wedding of Jack Bunsby and Mrs. MacStinger recalls Dombey's wedding. It is one of only three horizontal plates in the novel, and it clearly parallels the first one (the second is the dark plate of Carker's flight) in showing a wedding procession with the bride and groom at its head walking arm in arm, observed by casual onlookers in the background. Phiz's mastery of the crowded scene is by now evident, as each of the twenty-three human faces has its own distinct expression, and yet the composition and handling of shading focuses attention upon the main actors in the comedy.

Individual details either reflect the main idea of capture and imprisonment — or worse — or comment upon some aspect of the marriage. And at least one may refer directly back to Edith: the poster, "Wanted/Some Fine/Young Men/Hector/Arnazon," recalls the amazon statuette which symbolized Edith's dominance in "Mr. Carker in his hour of triumph," as the detail, "Medusa," referring to Mrs. MacStinger, was echoed in Dickens' subsequent description of Edith. A further link with other strands in [108/109] the novel is the poster for "Black-Eyed Susan," a play by Douglas Jerrold about the marriage of a jolly sailor. We should remember that Susan Nipper (a name not unlike MacStinger in import) has often been described as possessing black eyes, and in taking over and marrying the malleable Toots she has matched Mrs. MacStinger's capture of Bunsby, if somewhat more benignly. Several animals are emblems for Jack Bunsby in his present woefull state: the cows and sheep being led through the street (a procession which mirrors the main subject much as the funeral does in "Coming home from Church"), and the carcasses of animals (including two detached hearts) hanging up outside Smashem the butcher's next to the jolly Tar, suggest that the capture is to be followed by a slaughter, at least symbolically; the pig, tethered by the hind leg and striving to escape his little owner, reflects Bunsby's present state of mind; and the caged birds over the hung up sailor's hat predict his future state as a married man. The chickens, on the other hand, are probably a humorous reference to the party of women following in the train of the happy couple.

But this is not all. Among various other posters, the list of turnpike tolls for horse, mule, and donkey suggests that Bunsby is henceforth a servile beast. "She Stoops to Conquer — recalling that initially Bunsby managed Mrs. MacS. rather than the other way around — and "La Mariage [sic] Force" hardly require comment, while other posters use naval imagery: the "Wanted" poster already described, and one reading "Clipper/ Schooner/Wasp" (cf. MacStinger) on one steel, "Clipper/ Schooner/Triumph" — appropriate in a different way — on the other. Finally, as the ultimate emblem of Jack Bunsby's fall and capture, his walking stick, symbol of masculine authority (it is much in evidence in the plate "Solemn reference is made to Mr. Bunsby"), ingloriously sits in the muddy street, while he is allowed to hold only that symbol of female authority, Mrs. MacStinger's umbrella (cf. Mrs. Camp), and her reticule.

In claiming that "Another wedding" is a parody of other marriages in the novel (and especially of Dombey's). I do not mean to diminish the comic power of the Bunsby-MacStinger subplot. But I am suggesting that without this and certain other illustrations, the links between comic and serious story strands and the dominance of the woman-as-predator theme would not be as [109/110] readily evident. Browne seems to have invented the emblematic details to illustrate this theme, but it is probable that Dickens also stressed the theme to him. In the passages describing Bunsby's wedding, the text repeatedly refers to capture, sacrifice, and victims, and to the danger of all women: "The Captain saw ... a succession of man-traps stretching out indefinitely —, a series of ages of oppression and coercion, through which the seafaring line was doomed" (ch. 60, p. 609).

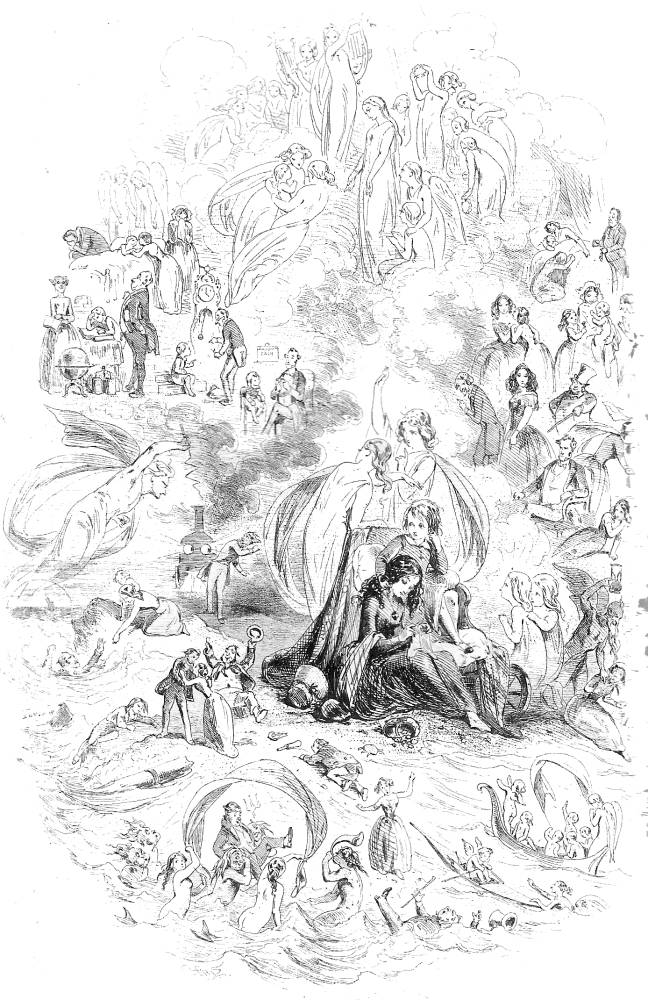

Frontispiece to Dombey and Son [illustration 74]. Click on image for larger picture and additional information.

Considered by absolute standards as either art or interpretation, the frontispiece to Dombey and Son is not a great work; it has "too much in it," as Dickens complained of the wrapper, leading to an effect — on first sight, at least — of fragmentation. Conceptually, however, it is related to concerns central to Dickens' artistic vision. The novel's final passage has Dombey and a new little Florence and Paul (his grandchildren) on the beach, and it evokes the first Paul, who "lay upon a little bed beside," while the new Paul is "very strong" and can "run about" (ch. 62, p. 624). The sea imagery which so dominates the first part of the book up to Paul's death — signifying at once life, death, and afterlife — is only faintly revived in the conclusion, but it forms the basis of Phiz's frontispiece. From the evidence of the instructions for the Chuzzlewit frontispiece, it appears likely that the general conception of the one for Dombey was specified by Dickens, but the particular working out left to Browne. As he so frequently did with allegorical compositions, Browne divided this etching into distinct sections (employing different characters and imagery), and he united the lower half with sea imagery.

As in the wrapper, the sea is at the composition's base, but the position of the shore is above; there are no other obvious connections between wrapper and frontispiece. Certain characters are given an allegorical watery fate, depending on their moral deserts, but the treatment ranges from the serious to the slapstick. Major Bagstock, for example, flounders in the waves, about to go down, while Miss Tox at the water's edge acts concerned. What Phiz is probably conveying here is the touch of corruption in Miss Tox's character which temporarily caused her to admire the Major. But, cleansed by the waters (from which she is rescued by a cupid in a scull), she is ultimately saved by her selfless love for Dombey. These figures in the sea are linked to [110/111] the large central group of Florence, Paul in his beach chair, and four angels, some of whom look up and wave to the children. Paul and Florence are here as in chapter 8 (p. 78), on the beach "with Florence sitting by his side at work." Compositionally this central group is linked with the angels at top center, toward whom two angels ascend, holding an infant Paul in their arms. A motherly angel welcomes him; she may represent Paul's mother in heaven, for Polly Toodles' assertion that "good people turn into bright angels and fly away to Heaven" (ch. 3, p. 18) is not necessarily regarded by Dickens as mere folk-superstition.

If the angels are Dickens' idea, Phiz's conception of them seems to be his own, but very much influenced by late Romantic art, in particular the work of Moritz Retzsch. There are similarities between the large group of angels in the Dombey frontispiece and an outline engraving in Retzsch's Fancies and Truths (published with English text in 1831, in Leipzig), "The Sleep of Infancy" (Plate 6). To be sure, Retzsch's subject is sleep rather than death, and the arrangement is not identical; but the basically triangular design with a harp-playing angel at the apex is similar, as are the embracing, younger angels at the harper's left. Further, Retzsch's single harp is decorated at top right with a flower and at top left with a star, while Phiz's right-hand harp terminates in a flower, the left-hand one in starry rays; and the way of surrounding the group with clouds is quite similar.

Two other images of death in the frontispiece present it as terrible rather than benign: Mrs. Skewton, looking terrified as she drops her fan, is accosted from behind by both a grinning Father Time with an hourglass which has run out, and a skeleton with a spear, traditional figures of death which were ubiquitous in the nineteenth century and earlier. Directly opposite this group, at the left, Carker's fate is depicted: an avenging spirit threatens him with a lightning bolt while he is pursued by a locomotive engine. (Interestingly, Phiz has anthropomorphized the engine much in the style of contemporary satirists of the 1845 railway panic (For examples of such locomotives in George Cruikshank's work of a few years earlier, see my article, "Dombey and Son and the Railway Panic of 1845). The two angels behind Paul and Florence appear to look at this horrible scene and shield the children from it, a connection which helps somewhat to unify what is altogether a rather diffuse allegory. It is perhaps also significant of Dombey's gradual moral progress that the black clouds (or smoke) arising from the train surround Mr. Dombey, but then are covered by [111/112] white ones in the angelic scene at the top. From the two cherubs kneeling at the right of the central group a parallel column of white clouds ascends.

With the frontispiece there appears a title page vignette showing a sneaky Grinder reading to an oblivious and magisterial Captain Cuttle. At first glance, this etching appears to illustrate a minor incident (ch. 37, p. 386) that bears no connection with the frontispiece facing it in the bound volume. Yet a definite, if ambiguous, connection exists. The cloud of smoke from the Captain's pipe is not merely incidental, for it all but obscures the map on the wall behind him, leaving visible only its title, "The World." Apart from a visual parallel with the clouds in the frontispiece, this would seem to imply that Captain Cuttle as a representative of the Wooden Midshipman — the company of the virtuous — blocks out The World — the materialistic civilization that produces Carkers and Dombeys, the opinion of which obsesses Dombey until his final conversion to the other party. But in the context such a meaning must remain double-edged: the Captain's innocence is also naiveté, as he is unaware of Rob's deceitfulness and is incapable of fathoming Carker's masks. Whether or not we can attribute this ambiguity to a conscious intention by artist or author, it does seem to expose profound moral ambiguity in the novel itself.

This particular illustration is important for its illumination of an almost subliminal aspect of the novel, not necessarily for the brilliance of the artist's conscious insight. Even the theme of the predatory female has a complexity which probably was not fully recognized by Dickens or even Browne. The explicit theme of Dombey and Son seems to be that mercenary and power-hungry men like Dombey and Carker make victims of women; there is no consistent recognition in the text of the paradox that such men are simultaneously the prey of these women. It is the illustrations which bring out the complexity, through comic parallels and emblematic details. I do not mean to suggest that Phiz had greater insight than Dickens; rather, he sometimes saw different things, just as the need to choose subjects for illustrations sometimes led Dickens to see possibilities in his novel not made explicit in the text. And this phenomenon is one of the chief reasons why as Dickens critics we disregard the illustrations only at our peril.

Created 2001 Last modified 9 July 2023