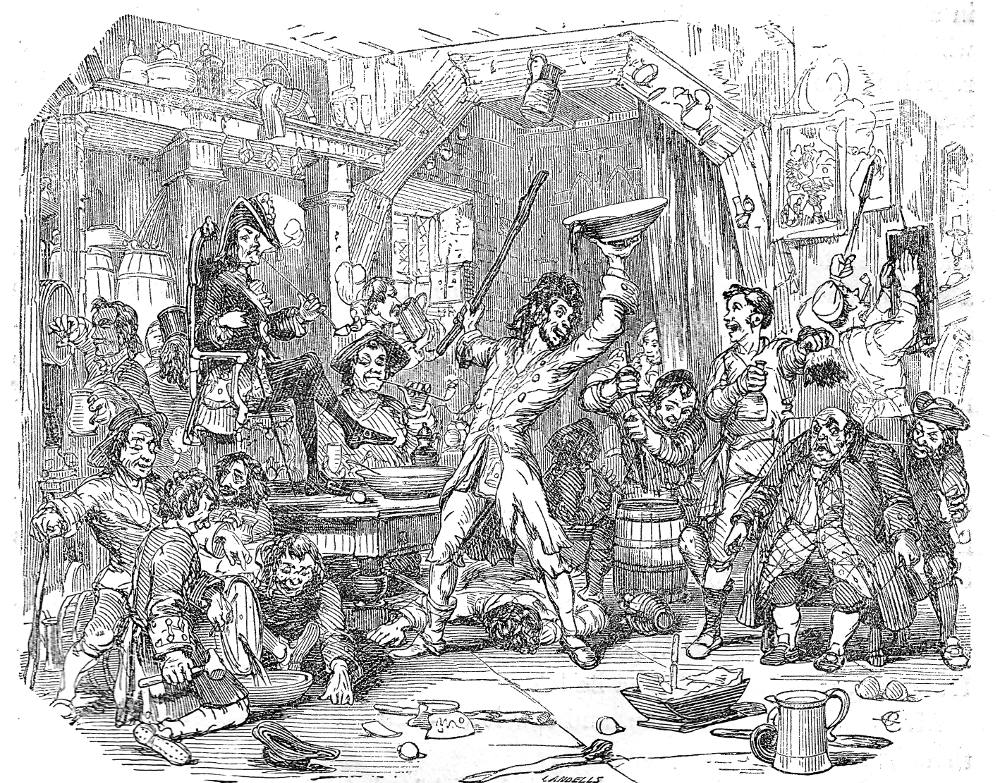

A Raid on the Bar by George Cattermole. 3 ⅝ x 4 ½ inches (9.2 cm by 11.5 cm). Vignetted, wood-engraved. Chapter LIV, Barnaby Rudge. 21 August 1841 in serial publication (fifty-first full-page plate in the series). Part 28 in the novel, serialised in Master Humphrey's Clock, Vol. III (part 70), 250. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Context of the Illustration: Hugh leads the rioters into The Maypole

"These lads are thirsty and must drink!" cried Hugh, thrusting him back towards the house. "Bustle, Jack, bustle. Show us the best—the very best — the over-proof that you keep for your own drinking, Jack!"

John faintly articulated the words, "Who’s to pay?"

"He says 'Who’s to pay?'" cried Hugh, with a roar of laughter which was loudly echoed by the crowd. Then turning to John, he added, "Pay! Why, nobody."

John stared round at the mass of faces—some grinning, some fierce, some lighted up by torches, some indistinct, some dusky and shadowy: some looking at him, some at his house, some at each other—and while he was, as he thought, in the very act of doing so, found himself, without any consciousness of having moved, in the bar; sitting down in an arm-chair, and watching the destruction of his property, as if it were some queer play or entertainment, of an astonishing and stupefying nature, but having no reference to himself — that he could make out — at all.

Yes. Here was the bar — the bar that the boldest never entered without special invitation — the sanctuary, the mystery, the hallowed ground: here it was, crammed with men, clubs, sticks, torches, pistols; filled with a deafening noise, oaths, shouts, screams, hootings; changed all at once into a bear-garden, a madhouse, an infernal temple: men darting in and out, by door and window, smashing the glass, turning the taps, drinking liquor out of China punchbowls, sitting astride of casks, smoking private and personal pipes, cutting down the sacred grove of lemons, hacking and hewing at the celebrated cheese, breaking open inviolable drawers, putting things in their pockets which didn’t belong to them, dividing his own money before his own eyes, wantonly wasting, breaking, pulling down and tearing up: nothing quiet, nothing private: men everywhere — above, below, overhead, in the bedrooms, in the kitchen, in the yard, in the stables — clambering in at windows when there were doors wide open; dropping out of windows when the stairs were handy; leaping over the bannisters into chasms of passages: new faces and figures presenting themselves every instant—some yelling, some singing, some fighting, some breaking glass and crockery, some laying the dust with the liquor they couldn’t drink, some ringing the bells till they pulled them down, others beating them with pokers till they beat them into fragments: more men still—more, more, more — swarming on like insects: noise, smoke, light, darkness, frolic, anger, laughter, groans, plunder, fear, and ruin!

Nearly all the time while John looked on at this bewildering scene, Hugh kept near him; and though he was the loudest, wildest, most destructive villain there, he saved his old master’s bones a score of times. Nay, even when Mr Tappertit, excited by liquor, came up, and in assertion of his prerogative politely kicked John Willet on the shins, Hugh bade him return the compliment; and if old John had had sufficient presence of mind to understand this whispered direction, and to profit by it, he might no doubt, under Hugh’s protection, have done so with impunity. [Chapter the Fifty-fourth, 249-51]

A Cattermole Anomaly — An Action Scene

The illustration is unusual among Cattermole's contributions in that he has subordinated the architectural elements to the vigorous action offered by Dickens's characters. Once again, Cattermole describes the interior of The Maypole, but how different is this riotous scene in the Common Room from those earlier in the novel. Once again, as in Chapter Twenty-five's Old John Asleep in his Cozy Bar, we are in the seventeenth-century public house's principal room for the entertainment of travellers. Previously, the publican, John Willet, was very much in control, and the majority of the customers were his old cronies and local village characters. Now Cattermole foregrounds Hugh, roaring drunk, and Sim Tappertit, enthroned and directing his followers. Willet is lost among the rioters, trussed up in one of his own comfortable chairs and powerless to stop the vandalism and depredation of his stock of liquors and wines.

Even though he has enough advanced warning from the sounds of the approaching rioters to put up the shutters and lock the stout front door, stupified John Willet fails to do so. He had lately argued with his cronies that the King would speedily put down any such activity, and his friends had gone off to witness the proceedings in London in the firm belief that the mob's depredations would be confined to the capital and its immediate suburbs. And then, without little warning, Maypole Hugh appears at the head of a large body of armed men and forces his way into Willet's sanctum sanctorum — his bar.

Cattermole takes his cue from Dickens. Since the author describes various rioters "turning the taps, drinking liquor out of China punchbowls, sitting astride of casks" the illustrator provides instances of such behaviour, observed in horror by a stunned publican (right) from his own familiar armchair. In addition to a group tapping a keg and pouring its contents into a bowl (left) Cattermole has introduced a broken China bowl (centre) and has Hugh, ragged and hairy, raising another such ceramic bowl above his head, the liquor overflowing onto his head. As Hugh holds aloft his gigantic bludgeon, he addresses John, roaring with laughter as he contemptuously responds, ""Pay! Why, nobody." Meantime, Sim Tappertit, in his usual military finery, has assumed a position of command in an armchair placed on the room's chief table. In fact, his position, dress, and haughty attitude of command are all entirely the illustrator's invention.

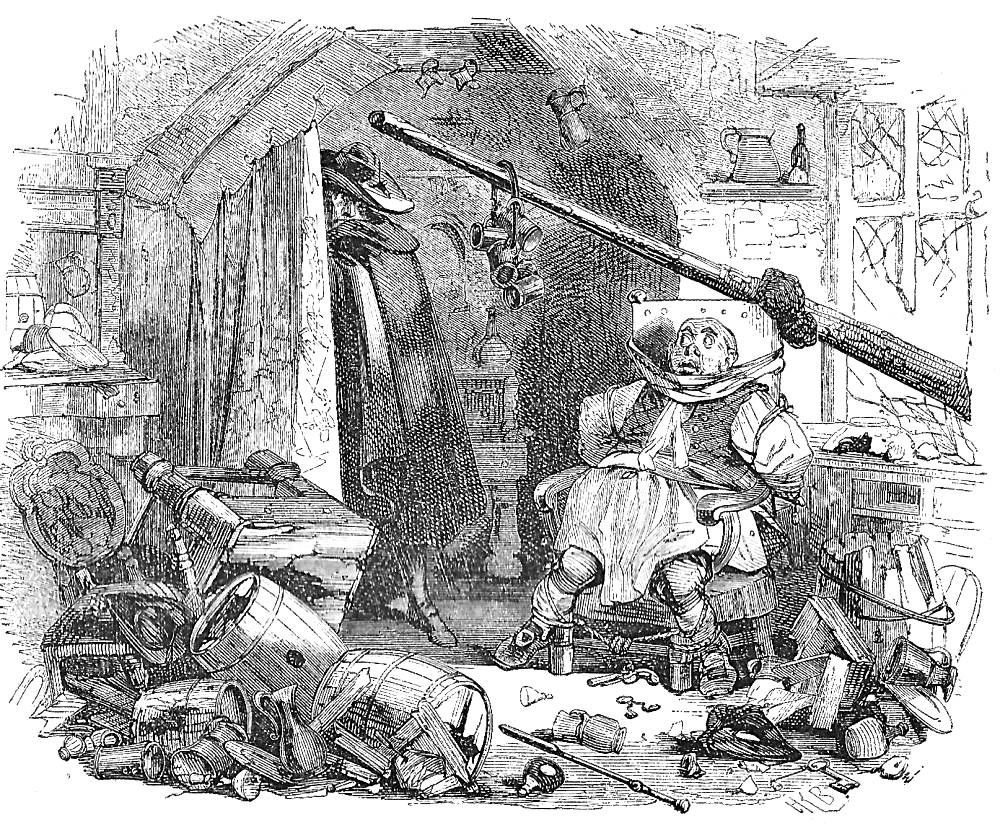

Cattermole's vigorous depiction of the mob's ransacking the bar at The Maypole here leads directly into the next illustration, in which Phiz shows John Willet, trussed up in his chair, pondering the vandalism (epitomised by the pole thrust through the front window) as a mysterious stranger enters through another window. The text leads to suspense as Dickens tantalizes the reader with the possibility that Ned Dennis will hang the publican; in the next illustration, the arrival of the mysterious stranger intensifies the reader's concerns about the publican's safety. In particular, Dickens and Phiz keep the reader in suspense about the intentions and identity of the black-caped intruder.

Parallel Illustration by Phiz for the next chapter

Phiz's study of the distressed publican trussed up like a turkey by the rioters, Old John at a Disadvantage (28 August 1841)

Related Material including Other Illustrated Editions of Barnaby Rudge

- Dickens's Barnaby Rudge (homepage)

- George Cattermole, 1800-1868; A Brief Biography

- Phiz's Original Serial Illustrations (1841)

- Cattermole and Phiz: The First Illustrators — A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley's six illustrations (1865 and 1888)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition illustrations (1867)

- Fred Barnard's 46 illustrations for the Household Edition (1874)

- A. H. Buckland's 6 illustrations for the Collins' Clear-type Pocket Edition (1900)

- Harry Furniss's 28 illustrations for The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Barnaby Rudge. Illustrated by Hablot K. Browne ('Phiz') and George Cattermole. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841; rpt., Bradbury & Evans, 1849.

________. Barnaby Rudge — A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. VII.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XIV. Barnaby Rudge." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition, illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. 213-55.

Vann, J. Don. "Barnaby Rudge in Master Humphrey's Clock, 13 February 1841-27 November 1841." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. 65-6.

Created 4 January 2006

Last modified 30 September 2020