ove, romance and courtship are central themes in Victorian literature, and the same can be said of Victorian art. In an age when marriage and heterosexual relationships were placed at the heart of middle-class life as part of the doctrine of home and homemaking, such representations embody a conventional notion of how society should be structured. Indeed, painting and illustration provide a mirror of traditional behaviours and map the various stages as couples meet, marry and (usually) produce children.

Left to right: (a)A.B. Houghton’s illustration of The Meeting of the Prince and Badoura; (b) Frederic Leighton’s The First Kiss; (c) Houghton’s treatment of married bliss in an illustration of exquisite and life-affirming beauty, Wed Last Spring.

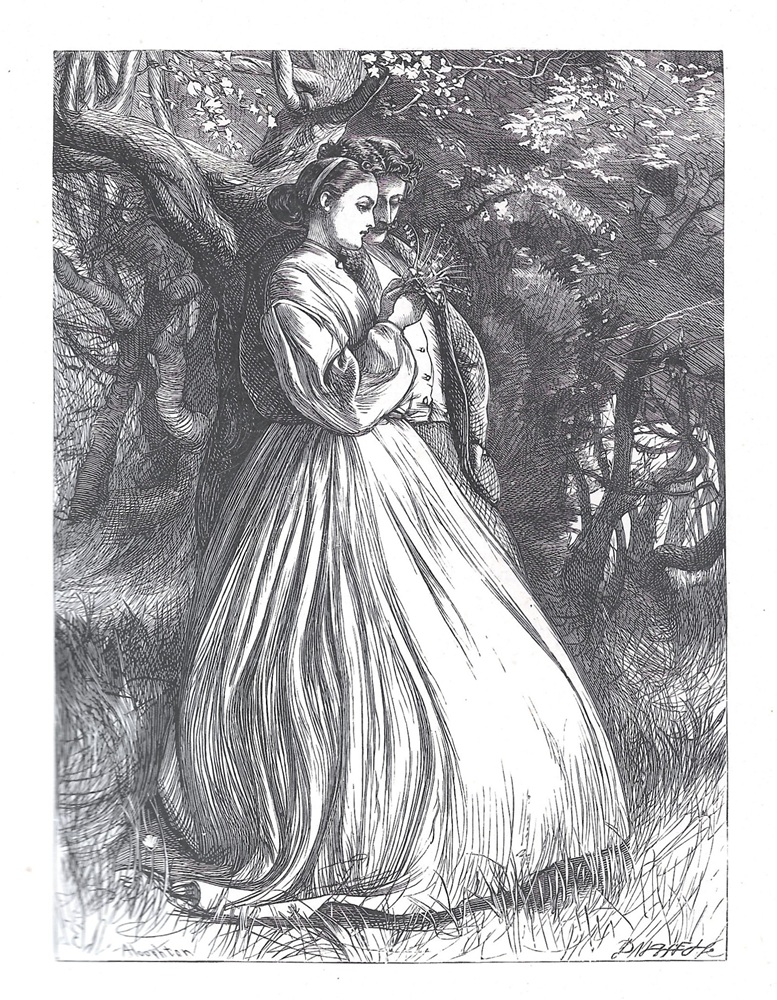

It is noticeable that many graphic designs, especially those in the style of ‘poetic realism’ known as the Sixties, are concerned with the initial encounter and the point of intimate contact in the form of a kiss. A.B. Houghton’s The Meeting of the Prince and Badoura in Dalziels’ Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (1865) is a good example, and so is Fred Leighton’s The First Kiss for George Eliot’s Romola (1863). Each materializes romantic love, which is epitomized by the description in the Nights: ‘They ran into each other’s arms and were locked in the tenderest embrace, without being able to utter a word from excess of joy’ (328). Courtship, often represented in the form of passionate embraces, can be further traced in illustrations by J.E. Millais, and the simple pleasures of a couple’s togetherness are also represented in designs by J.D. Watson and Alfred Cooper. Created as visual responses to sentimental poems, these images idealize the process of union; the same can be said of illustrations of marriage.

Some passionate embraces, along with the simple pleasures of companionship. Left to right: (a) Millais’s Love; (b) Millais, Locksley Hall; (c) Watson, A Summer’s Eve in a Country Lane.

In so doing they assert and are closely informed by conventional ideas of gender roles in a patriarchal society in which men were the dominant partners and women had few rights. As generations of critics have observed, bourgeois society expected the ‘weaker sex’ to be ruled by men and to conform to specific and often limiting roles within the household. Martha Vicinius (1972) sums up the situation in a feminist analysis, noting how ‘the perfect lady’s sole function was marriage and procreation’ which reflected a ‘“natural” submission to [male] authority and innate maternal instincts’ (x). At the same time, these procreating females were supposed to be sexless. In the infamous words of the Victorian theorist William Acton in The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs (1857):

There are many females who never feel any sexual excitement whatever. Others, again … become, to a limited degree, capable of experiencing it … The best mothers, wives and managers of households, know little or nothing of sexual indulgences. As a general rule, a modest woman seldom derives any sexual gratification for herself. She submits to her husband only to please him. [102]

This statement is passed off as factual but is of course weighted with generalizations and gender politics. Terms like ‘Others’ and ‘limited degree’ can barely be described as scientific, and the final claim, that women exist only to serve (or ‘please’) men is presented as a given, the type of assumption that underpins paintings such as Edgar Hicks’s Women’s Mission: Companion of Man (1863) and Millais’s treatment of Lucy Robartes’s relationship with her husband Mark in his illustration for Trollope’s Framley Parsonage (1860). Whether in the bedroom or in everyday domestic life, women are shown to be there for their men as a pleasure, or as a support in difficult times.

The wife to the rescue. Left: Hicks, Women’s Mission; right: Millais’s illustration of Lucy supporting Mark. Both images point to the notion of the faithful, supportive wife, even though both husbands have engaged in ill-considered dealings that put them in debt; the crisis shown is the moment when final demands are received.

But is this model monolithic – or is it, as Carol Jacobi suggests in a general comment on Victorian orthodoxies, more ‘fluid and unstable’ (Jacobi) than one might suspect, a discourse rather than an assertion of naturalized ‘reality’? Feminist critics have stressed the power-asymmetry of heterosexual relationships in the nineteenth century, and a glance at the examples given above suggests that a rigid gender-based structure is in operation and is projected as such in art. However, there is clearly a disjoint between what was believed and how some women, at least, were represented in painting, literature and illustration. It is obviously the case that Victorian fiction contains many iconoclastic representations of female selfhood – Becky Sharp in Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848), Collins’s Marian Halcombe in The Woman in White (1860) and M. E. Braddon’s Lady Audley in Lady Audley’s Secret (1862) are only a few; and a parallel type of strong, sexualized woman can be traced in visual material. We have only to think of Dante Rossetti’s menacing goddesses in paintings such as Astarte Syriaca (1877, Manchester City Art Gallery) and Lady Lilith (1866–68, Delaware Art Museum). These emasculating monsters play on male sexual anxiety, and are purely symbolic figures.

Rossetti’s menacing and ungovernable women – Astarte (left, whose vast figure looms out of the canvas), and right, Lilith, Adam’s wife in Judaic myth before Eve made her appearance.

But more complicated are the ways in which many artists manage to negotiate a space in which to represent women who do not comply with the stereotype of the passive or helpless female. Working within traditional models and formats, these challenging representations test the limits of conventionality and their audience’s belief-system. This approach, which plays on ambiguity and the complications of female experience, can be traced in two recurring and overlapping motifs: the ‘waiting woman,’ who is usually embowered in a room, and the ‘woman who secretly meets her lover in the countryside or garden.’ In the following sections I examine how each of these can be read two ways – as an assertion of the ideologically acceptable, and in more nuanced images of gender-busting defiance and female strength. In particular I want to show how some works contain both, contradictory messages. I also consider the consequences of ‘waiting too long.’

Visual Art and the Waiting Woman: Passive and Passionate

On the face of it, the image of the ‘waiting woman’ is a purely patriarchal construction, with women being presented as inert figures awaiting the arrival of a man. In some cases the female is entirely passive and reactive, a situation symbolized by Edward Burne-Jones’s version of the Sleeping Beauty in the Sleeping Princess (1874). Here the subject is literally fast asleep and denied life until she is reanimated by a kiss – a mythological trope that reflects uneasily, and tellingly, on real-life middle-class women’s chances to make a life; otherwise without status, they await their own particular princes to awaken them.

Burne-Jones’s meditation on the passivity of women, The Sleeping Princess.

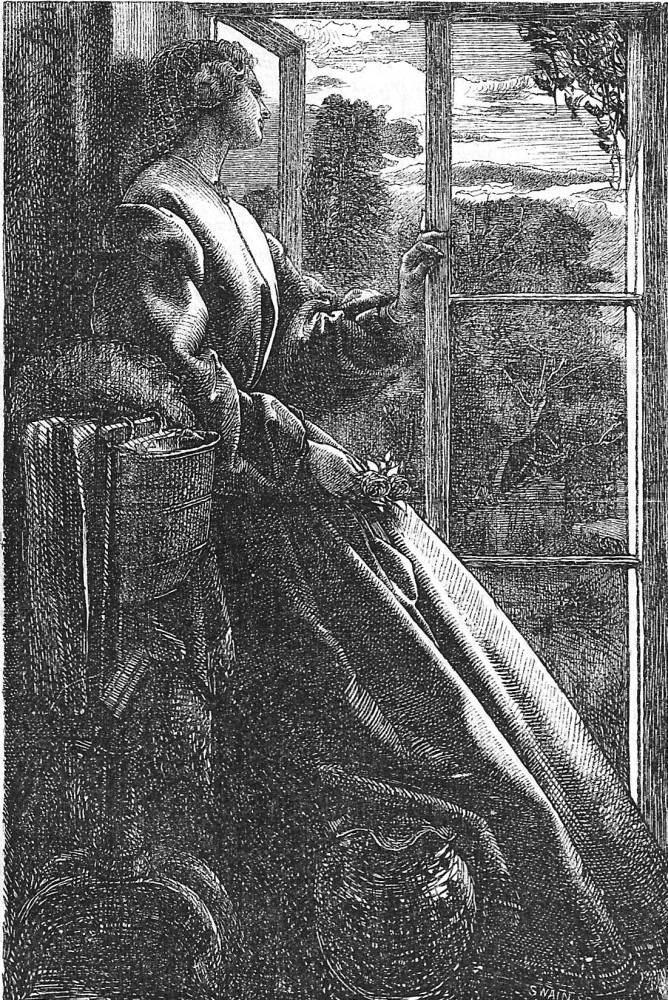

Such allegorical paintings provide a convenient means of commenting on women’s status, with Millais’s The Knight Errant (1870) and The Crown of Love (1875) offering a distinctive take on female helplessness and the need for male validation. Fred Sandys also offers a traditionalist view in From My Window (1861), which accompanies a feeble poem by Fred Whymper about a woman awaiting her lover. The treatment here, again, is purely stereotypical, rooting the notion of female passivity in modern life. The figure is depicted as a gentle young girl, delicately placing one hand on the window frame while the other holds a posy; an elaborate sewing-box is placed so as to link her domestic activities; and the outer space (associated with male activity) and the enclosed room (the domain of women) are sharply differentiated. This is an ideal image of the woman who awaits a man and will become a home-maker: all she wants now, once he arrives, is a marriage proposal. In Maria Pointon’s terms, it is a typical depiction ‘of women defined by the invisible … male’ (qtd. Jacobi).

The woman needs a man to rescue her. Left to right: (a) Millais’s The Knight Errant; (b) the same artist’s The Crown of Love; and (c) Sandys’s From My Window.

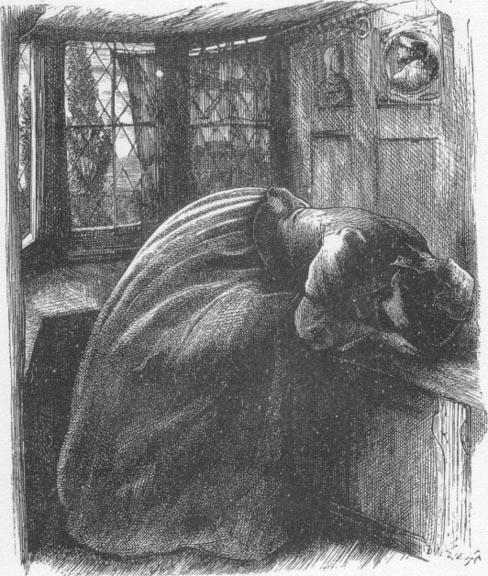

This version of female experience could be described as the ‘Mariana’ complex – a type of visual representation that recalls Mariana’s waiting for Angelo in Shakespeare’s Measure of Measure. It is more directly influenced, however, by Tennyson’s ‘Mariana,’ which featured in the illustrated ‘Moxon Tennyson’ (1857) with a design by Millais. In fact, Millais produced two versions: one as a wood engraving in the Moxon edition and another in the form of an oil painting (1851). These versions are interesting because they represent the conventional and the testing of the conventional. In the printed treatment Mariana is purely in need of her man: her longing is embodied in her prostration, and her feelings of lonely confinement, as in a prison, are suggested by the claustrophobic space and the bar-like verticals of the coffered walls.

Millais’s wood engraving of Mariana in the ‘Moxon Tennyson.’

On the other hand, the painted version is far from straightforward and, while the woman is imprisoned and seemingly unable to escape, she can still be read as an image of female power as much as submissiveness. Millais balances the two possibilities, inscribing that dialectic in an iconography of significant details, symbolic colour, space and the treatment of Mariana’s figure.

Her status as a woman only defined in relation to a man is suggested, Carol Jacobi argues, by the presence of a sugar caster which appears as a tiny detail in the background altar, a phallic sign which also appears, with sexual connotations, in Millais’s The Bridesmaid (1851): the man is not there, but he is present symbolically (Barringer 92). Other signs also point to a subordinate passivity: the sharp differentiation of space, inner and outer, is again present, and the fallen leaves imply her decay awaiting for the generative arrival of the male. Millais’s deployment of blue, the colour of the faithful Virgin Mary in Renaissance and medieval art, is also a conventional signifier of purity and fidelity.

Millais’s painted version of Mariana.

Yet Mariana’s strength is present too. Though her robe is blue, Millais includes a vivid red in the cover of her stool – the archetypal colour of passion and sex. This balance accentuates the concept of Mariana’s sexuality asserting itself beyond the constraints of sexless passivity, a notion that is embodied in the criss-crossed interaction of red and blue in the patterning of the window. Indeed, the window-design, an image of the Annunciation, is itself a dialectic of sexlessness and sex: the Virgin Mary is only defined by the arrival of Gabriel, but she welcomes his message, that she will be penetrated by the Holy Spirit – a ‘quasi-sexual event,’ as Barringer puts it (43), that symbolizes Mariana’s active desire. Rather than passively waiting, as in Tennyson’s poem, Millais’s Mariana is practically a coiled spring of desire; positioned in a contrapuntal pose, she is the very embodiment of suppressed energy. Her voluptuous figure further adds the implication of erotic self-awareness, is clearly gender-marked, and strongly differs from the bland sexlessness and androgyny of Burne-Jones’s women in The Sleeping Princess.

All of these elements cohere to suggest that this Mariana is not at all the stereotypical ‘waiting woman.’ Rather, her situation is used to foreground a passionate nature which is informed not with timid acceptance but intense, frustrated desire. In fact, Millais may also have considered other, more explicit demonstrations of her sexuality. In a preparatory drawing he places a piece of Mariana’s sewing on the table as she looks out of the window – an item, according to Jacobi, that links her to the poverty-stricken seamstresses of the period who had to chose between sweat-shop wages and prostitution, and were often thought of as ‘loose women.’ This suggestion can only be speculative, sewing being more often associated with homemaking, as in Sandys’s From My Window, but her pose, usually interpreted as a sign of stretching weariness, can be read, I suggest, as that of a prostitute displaying her figure to a potential client. Indeed, there can be little doubt that although Mariana is waiting for Angelo she is far from the passive innocent as eulogized in Coventry Patmore’s The Angel in the House (1854, 1863) and far from the hopeless figure of Tennyson’s poem.

Sandys’s Danaë in a pose that is markedly at odds with conventional rules of Victorian propriety.

Such active characters feature in the many other representations of waiting women, who, despite being confined, are sexually frustrated rather than the sexless recipients of their men’s attendance. Stymied by their domestic captivity, their desire is internalized and is only revealed in visual clues. Sometimes these are subtle, and sometimes they are startlingly explicit, as in Sandys’s erotic Danaë in the Brazen Chamber, which is variant on the type and acts as an illustration for A. C. Swinburne’s poem. The design, which includes a small detail of Zeus’s genitals, was suppressed when it was produced in 1866 and was only published in 1888; however, there seems to have been no objections to the rest of the image, which is a surprisingly candid representation of female arousal. This waiting woman is the very reverse of the stereotype: reflecting on Zeus’s recent visit or anticipating his return, Sandys shows her as a voluptuous figure with an eroticised pose and an ecstatic facial expression. Her flowing hair likewise acts as a powerful Victorian sign of sexual preparedness in an age when women’s hair was only released at bed-time, the exposed leg is decidedly provocative, and the artist reinforces the sexual message in the form of a bed with disturbed sheets. For sure, this woman is anything but a passive responder to male desire.

Such active, sexualized women also feature in many other representations of embowered maidens, particularly in the work of Dante Rossetti. The subject in The Blue Bower (1865, Barber Institute, University of Birmingham), is depicted as a self-assured individual and the same is true of Fair Rosamund in the painting of the same name (1861, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff). Both are portraits of Rossetti’s mistress, Fanny Cornforth, and in each work the artist stresses the woman’s sexual allure by emphasising her fleshly features and the redness of her hair and cheeks, which seem to be in a perpetual blush of arousal. Though waiting for a male, neither subject suggests the anguish of the situation, and neither is inert in the manner of so many treatments of the motif.

Left: Rossetti’s The Blue Bower, and right, The Blessed Damozel.

However, Rossetti’s handling of the theme is most interestingly explored in his versions of ‘The Blessed Damozel’ – in the form of his poem (1850, revised, 1881), and in his painting of 1871–78. Like Millais, Rossetti stretches the conventions of the ‘waiting woman’ theme, though this time he asserts its ambiguity in words and its illustrative canvas (Fogg Art Gallery, Harvard University). Both, again, are a balance of possibilities. On the one hand, the female is the epitome of purity, patiently awaiting the validation of her beloved. She has ‘three lilies in her hand’ (Rossetti 3), the symbols of virginity, and grieves her separation from her lover, a matter, in the poem, of her weeping (7), and in the painting in the form of her wistful expression and soulful eyes, ‘Her eyes were deeper than the depth/Of waters stilled at even’ (3). Yet she is replete with the properties of sexuality: her robe is ‘ungirt from clasp to hem’ (3) and her sensuality is suggested by her bosom warming the ‘gold bar of Heaven’ (3–4). Moreover, she is an active figure. In the painting Rossetti shows her vigorously leaning toward the earthly domain, with her scarf-like veil blowing around her as she fiddles frustratedly with a flower. Like Mariana in Millais’s image, she dynamically dominates the space, another recasting of the usual prostrate figure. Indeed, Rossetti subverts expectations by reversing the behaviour of the two lovers. This time, the male is presented in the predella as a prostrate figure, waiting, it seems, for a sign from his heavenly lover. She may be contained in paradise, but is noticeable that he is crammed into a small panel – condemned to wait for the beau who will never return. It is a telling rearrangement that questions gender roles and undermines the tropes of female helplessness by reassigning them to a man.

Illicit Meetings in Nature: The Waiting Woman in Gardens and Landscapes

All of these images are dense fields of possibilities as they incorporate what Jacobi calls ‘serious sexual poetry.’ The discourse of the ‘waiting woman’ has another manifestation in representations of women who leave the bower in order to rendezvous with their lovers somewhere in a landscape – often in the woods, but sometimes in other settings such as the coastline or riverside. This type was popular as a representation of romance, and for modern observers it might appear to be a small variant on a well-tried convention. However, the ‘waiting woman in the landscape’ is different from the ‘waiting woman in the bower’ in some fundamental ways and insists, once again, on the power of strong individuals.

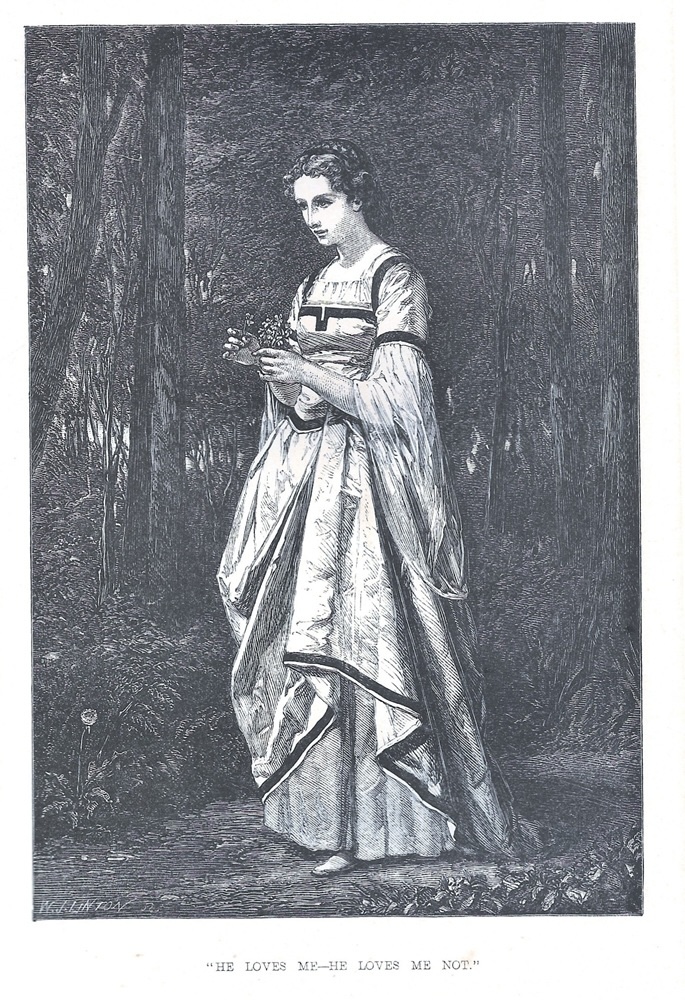

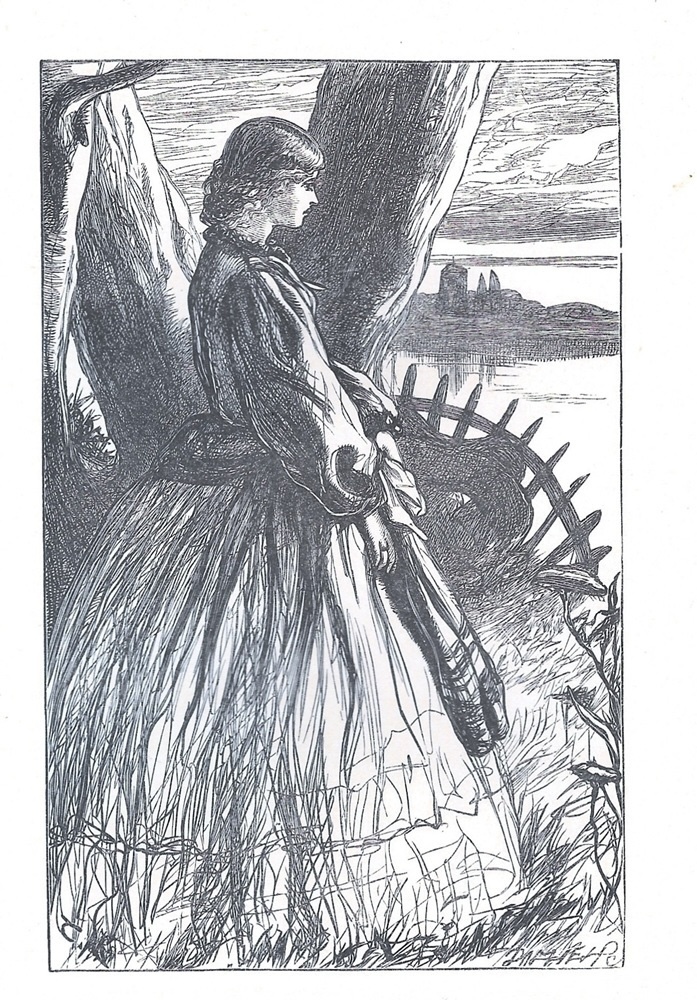

Two women in solitary pursuit of love in the unpredictable setting of the outdoors. Left: E. K. Johnson, He Loves Me – He Loves Me Not; right: Thomas Morten, Waiting by the River

First of all, the very fact that the woman is not contained in a room is an assertion, within Victorian culture, of transgressive behaviour. Practically, these are Marianas who have broken out of the prison of home and have gone, alone and unchaperoned, in pursuit of their men in the male domain of the non-home. The code of the ‘modest woman’ is subverted. Such behaviour was freighted with the charge of impropriety, if not scandal, and the many representations of this event are a daring celebration of women taking control of their own lives; what would have been frowned upon in reality can be relished in the escapist pages of a book or in paintings which act to bypass the confines of bourgeois taboos.

Sandys’s suggestive interpretation of Christina Rossetti’s ‘If he would come today.’

The single woman alone in the landscape might thus be read as a type of heroism, a sort of cathartic denial of social restrictions. It is noticeable, further, that visual artists often manipulate the motif in order to suggest the women’s sexual motivations, a process, in illustrated texts, that is sometimes expressed in a disconnection between the words and the image. Sandys’s design for Christina Rossetti’s ‘If’ (1866) is a good example. The poet’s lines are a purely traditional rendering of the heart-broken woman, another Mariana, who waits for her lover to arrive:

If he would come, today, today, today

O what a day today would be!

But now he away, miles and miles away

From me across the sea.

O little bird flying, flying, flying

To your nest in the warm west

Tell him as you pass that I am dying

As you pass home to your nest. [336]

Rossetti’s ‘weary world’ demands an image of a passive type – a pale and slender girl who is entirely defined by her relationship with her lover. Sandys, however, provides the very reverse. His waiting woman is a fleshly Rossetian type, closely linked to images of Fanny Cornforth, whose physical presence connotes a robust sexuality. Her biting of her let-down hair and clutching at the grass further suggest erotic frustration; the sea, which parts the lovers, might also be read not as a naturalistic detail but as a sign of passion, and Sandys emphasises the point by making the water turbulent and wave swept.

The natural world is more generally projected in this type of image as a metaphor of female sexuality which draws upon a wider tradition in visual art that connects women, with their power of procreation as the source of all human life, with nature. Its representation in Victorian culture is widespread in painting and illustration but is best explained in literary terms. Hardy’s novels provide several examples of the equation of women and nature – notably in Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891) and The Return of the Native (1878) and especially in the rustic meeting of Bathsheba and Troy in Far from the Madding Crowd (1874). Read in Freudian terms, the place of meeting is weighted with sexual suggestiveness and acts as metonym of Bathsheba’s genitals and pubic hair: “The pit was a … concave naturally formed … Standing in the centre, the sky overhead was met by a circular horizon of fern …The middle within the belt of verdure was floored with a thick flossy carpet of moss and grass intermingled.” The matching phallic symbolism, as Troy dances around her with his sword, is equally plainly asserted, culminating in Bathsheba’s inquiry, ‘Have you run me through?’ (210). As so often in Victorian culture, ‘nature’ and ‘human nature’ are intertwined.

Left to right: (a) Calderon, Spring-Time; (b) Millais, Waiting; (c) Calderon, Broken Vows

Visual art parallels this approach, immersing its lone female characters in verdant woods and gardens that symbolize female sexuality. Philip Calderon’s Spring-Time (1896, Private Collection) clearly represents women’s generative capacity, linking the new life of spring with a scantily clad heroine. Millais’s Waiting (1854, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery) similarly affirms the connection of women and nature; she is framed by a background of verdant trees and undergrowth and positioned within a foreground of vivid grass animated by energetic strokes and a play of light that counterpoints the suggestive darkness of the wood behind her. She may be placed in a static pose, but the natural setting points to an underlying eroticism as nature vibrates with energy. Calderon’s Broken Vows (1865, Tate Britain) also presents the same symbolism as two women –the betrayed lover and the new one – are met by a man in a garden of luscious fertility. The plants have emblematic significance, such as ivy for memory and fidelity, but the overall symbolic scheme is a representation of woman’s ‘natural’ function and natural, sexual desires. Variants can also be traced in the many illustrations of landscape settings where the lone woman is finally met by her lover.

Arthur Hughes, The Long Engagement.

Of course, both of these paintings – Broken Vows and Waiting – re-emphasise the notion of frustrated sexuality rather than its realization. The female characters may have taken their destinies into their own hands by going to meet their lovers, but they are just as confounded as those who remain closeted at home. In fact, other circumstances might intervene to prevent a suitable consummation. In Arthur Hughes’s The Long Engagement (1858, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery), the artist counterpoints desire and reality: the Pre-Raphaelite details – ferns, ivy, roses, a pair of mated squirrels – point to couple’s repressed eroticism, but their situation, being too poor to marry, countermands their instincts. All the poverty-stricken curate can do is look soulfully into the distance while his beloved contemplates their predicament. Surrounded by the densely-coloured, luscious abundance of nature, the characters’ faded and time-worn faces are a tragic sight; all natural phenomena regenerate, but they are only subject to decay.

Waiting Too Long

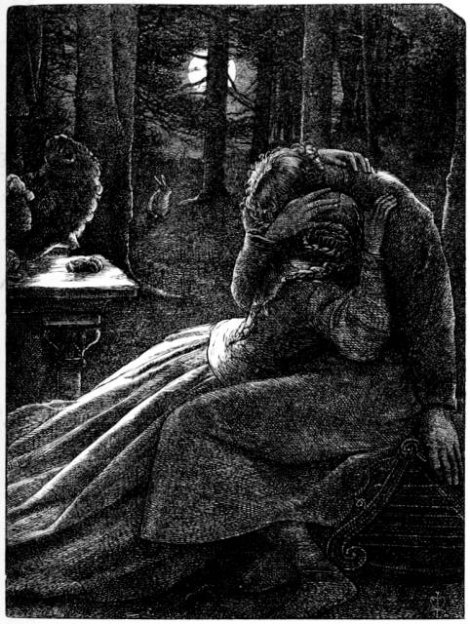

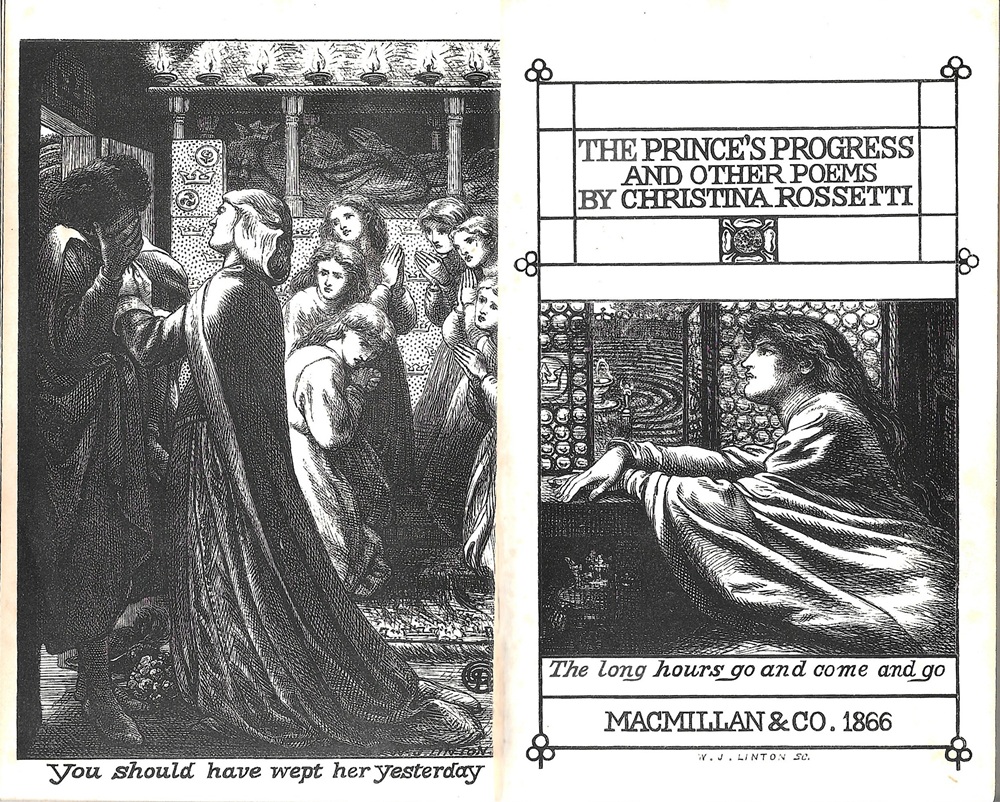

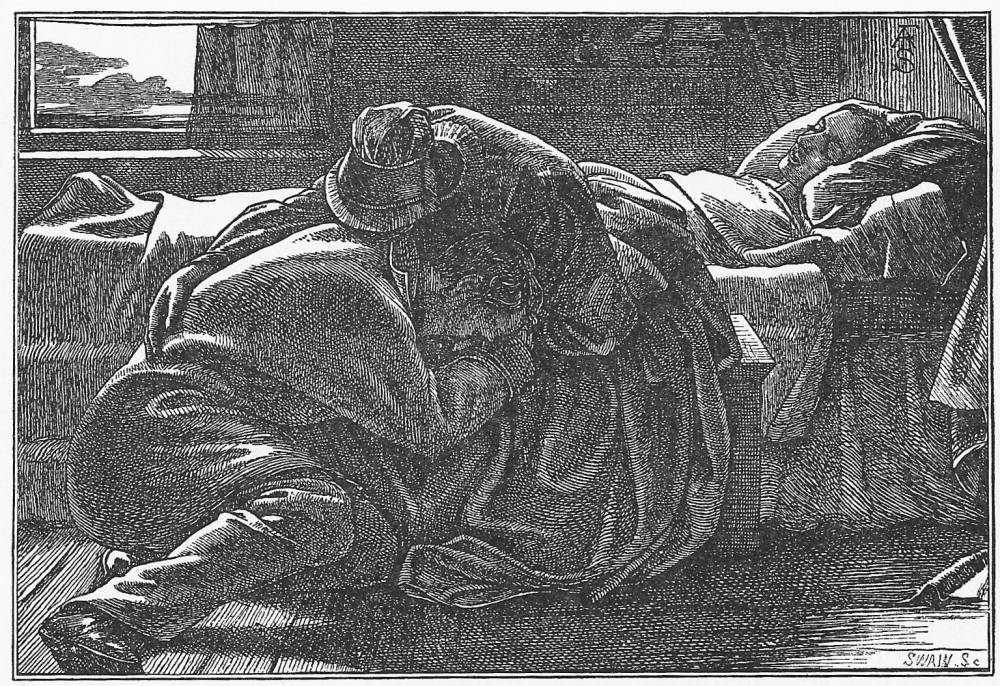

Left: Rossetti’s double-page design for his sister’s poem, ‘The Prince’s Progress’; right: Sandys, The Sailor’s Bride.

In all of these images women are forced to wait too long – and sometimes that endless delay is fatal. Two pieces stand out: Rossetti’s designs for Christina Rossetti's The Prince’s Progress (1866), and Sandys’s The Sailor’s Bride (1861). Each of these illustrates the consequences of the male lover’s tardiness; arriving too late, he finds his beloved has died. The Sandys image visualizes a sentimental poem by Marian E. James and is spoken by the dying bride, who is afflicted by some unknown illness; the closing lines are her final words as her lover comes into the room:

A hand is on the cottage door;

A face bends over the bed.

Too1ate! Too late hath Leonard come:

Love cannot raise the dead. [432]

And the same sentiment is expressed in Christina Rossetti’s verse as the Prince misses by just a day and is berated by the Princess’s attendant:

“You should have wept her yesterday,

Waiting up her bed:

But wherefore should you weep today

That she is dead. [30]

Both artists show the men possessed by grief, but the condemnatory words by Christina Rossetti are the most telling. It may well be, as I have tried to show, that the ‘waiting women’ are far from passive or de-sexualized, but it is certainly the case that they are condemned to define their lives, deaths, and destinies in relation to men. Despite women’s struggles, Victorian patriarchy ultimately remains the controlling power.

Related Material

- Sexuality and Gender in Victorian Illustration

- The Adoring Woman — Waiting, Left Behind, or Abandoned

- Sleeping Beauties in Victorian Britain: cultural, artistic and literary explorations of a myth

- Victorian Attitudes towards Sexuality and Sexual Identity — sitemap

Bibliography

Acton, William.The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs in Childhood, Youth, Adult Age and Advanced Life Considered in Their Physiological, Social and Moral Relations. 1857; London: Churchill, 1862.

Barringer, Tim. The Pre-Raphaelites: Reading the Image. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998.

Braddon, Mary Elizabeth. Lady Audley’s Secret. London: Tinsley, 1862.

Collins, Wilkie. The Woman in White. London: Sampson Low, 1860.

Dalziels’ Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. London: Ward, Lock, & Tyler [1865].

Eliot, George. Romola. First published with Leighton’s illustrations in The Cornhill Magazine

Jacobi, Carol. ‘Sugar, Salt and Curdled Milk: Millais and the Synthetic Subject.’ Tate Papers, no. 18 (Autumn 20212). Online at: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/18/sugar-salt-and-curdled-milk-millais-and-the-synthetic-subject James, Marian E. ‘The Sailor’s Bride.’ With an illustration by Sandys. Once a Week. 4 (1861): 434. Hardy, Thomas. Far from the Madding Crowd. 1874; New York: Hurst & Blackett, 1918. Patmore, Coventry. The Angel in the House. London: Macmillan, 1863. Rossetti, Christina. ‘If he would come today.’ With an illustration by Sandys. The Argosy (Midsummer 1866): 336. Rossetti, Christina.The Prince’s Progress.London: Macmillan, 1866. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. Poems. Ed. Oswald Doughty. London: Dent, 1977. Swinburne, A. C. ‘Danaë in the Brazen Chamber.’ With an illustration by Sandys, 1866; the illustration was printed in reproduced in The Century Guild Hobby Horse (1888), facing p. 147.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857. The ‘Moxon Tennyson.’ Thackerary, W. M. Vanity Fair. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1848. Trollope, Anthony. Framley Parsonage. First published with illustrations by Millais in The Cornhill Magazine, 1860–61. Vicinius, Martha., ed. Suffer and be Still.1972; London: Methuen, 1980. Whymper, Fred H. ‘From my Window.’ With an illustration by Sandys. Once a Week 5 (June – December 1861): 237–38. Created 30 November 2025