Books Devoted to Hardy's Short Fiction, 1982-2017

Kristin Brady's The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy: Tales of Past and Present (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1982). Pp. xii + 235.

Pamela Dalziel's Thomas Hardy: The Excluded and Collaborative Short Stories (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992). Pp. xii + 235.

Martin Ray's Thomas Hardy: A Textual Study of the Short Stories (Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 1997). Pp. xiv + 357. ISBN Hardback: 1859282024. $149.95 USD.

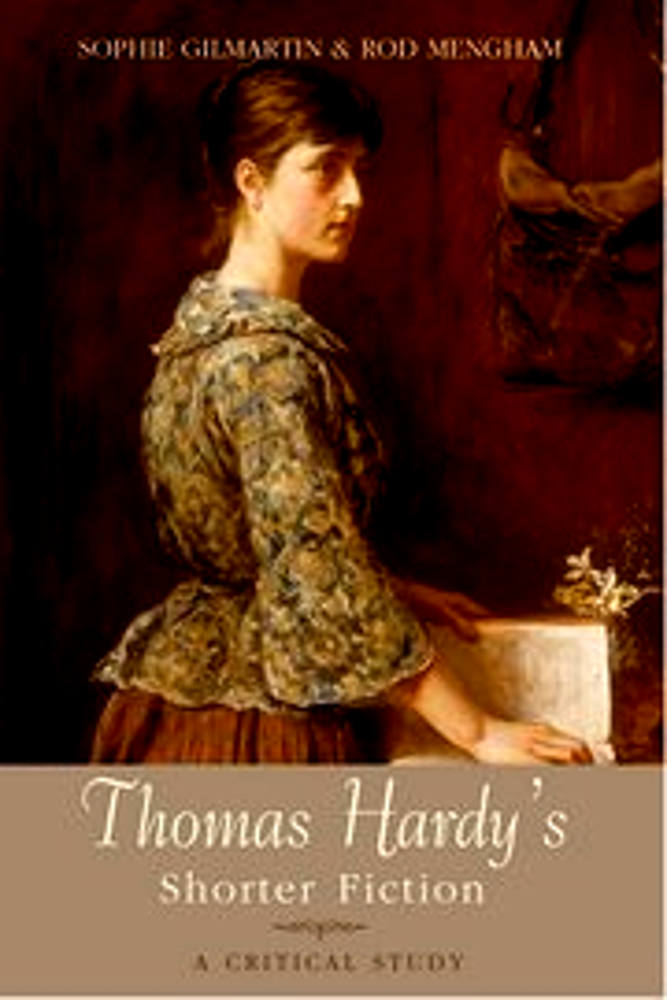

Sophie Gilmartin and Rod Mengham's Thomas Hardy's Shorter Fiction: A Critical Study (Edinburgh: Edinburgh U. P. 2007). Pp. xii + 148. ISBN Paperback: 9781474407632. Hardback £65.00; paperback £16.99.

Juliette Berning Schaefer and Siobhan Craft Brownson's Thomas Hardy's Short Stories: New Perspectives. The Nineteenth Century. London and New York: Routledge, 2017. xiii + 200 pp. ISBN 9 78 1 4724 8003 3. $148.25/£90.33; ebook/Kindle $54.95/£39.98.

Introduction: Away from An Orientation on Hardy's Three Anthologies and Towards the Stories' Periodical Origins.

The following discussion, which concentrates on the recent volume of criticism edited by Schaefer and Brownson, also surveys the scholarship and criticism on tenof Hardy's best-known short stories, comparing approaches of different critics over the past thirty-five years. During this period, critics of Hardy's short fiction have shifted from examining the stories in just their final forms — that is, in Hardy's anthologies (published from 1888 to 1913) — to considering the American and British periodicals in which these stories first appeared. However, although the 2017 volume of criticism, unlike its predecessors, at least reproduces some of the illustrations that accompanied the original periodical publications, no critic has adequately integrated an analysis of the accompanying illustrations (for the most part, lithographs) into an assessment of the broad reading public's reception of these stories as commercial magazine fiction.

Publishing in commercial upscale magazines provided Hardy with considerable income and enabled him to reach a much greater number of readers than was the case with his limited-run anthologies Wessex Tales (Macmillan, 4 May 1888), A Group of Noble Dames, (Osgood, McIlvaine, on 30 May 1891) Life's Little Ironies (Osgood, McIlvaine, 22 February 1894), and A Changed Man and Other Stories (Macmillan, 24 October 1913). By far the preponderance of his work in the shorter fiction genre Hardy wrote for "the high-class illustrated weeklies" (Law, "Neither Tales nor Short Stories?" 15): The Illustrated London News, the Graphic, and Harper's Weekly, although some stories such as "The Withered Arm" first appeared in such non-illustrated monthly magazines as Blackwood's, and occasionally in illustrated monthlies such as Harper's New Monthly Magazine, as well as such provincial newspapers as the Leeds Mercury and The Bolton Weekly Journal. Perhaps the essay in the Schaefer and Brownson volume that best addresses the issue of public reception of Hardy's stories in late-nineteenth-century periodicals is Graham Law's "Neither Tales nor Short Stories? Issues of Authorship, Readership, and Publishing in A Group of Noble Dames," although — somewhat surprisingly — Law does not discuss or even reference the illustrations that accompanied these ten stories which Hardy wrote over thirteen years and published in five different periodicals, the chief of these being the Graphic. Despite Hardy's enjoying wide readership over the last two decades of the nineteenth century in Great Britain and America, twentieth-century critics generally failed to appreciate or even acknowledge this substantial body of work until 1982.

Modern critics, appreciating the psychological subtleties and narrative complexities of the short stories of such twentieth-century writers as James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, and Katherine Mansfield, have consistently undervalued Thomas Hardy's short fiction. Although numerous books of criticism have dealt in depth with the most significant of the Wessex Novels, modern criticism includes only a handful of books devoted entirely to the short stories, most of which appeared within the past twenty-five years, the exception being Kristin Brady's The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy (1982). Moreover, studies, such as Arlene M. Jackson's Illustration and the Novels of Thomas Hardy (1981), that should have considered Hardy's longer works of short fiction (for instance, the novella The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid and the framed tale A Group of Noble Dames) have not. Martin Ray in 1987 and, much more recently, Gilmartin and Mengham (2007) and Schaefer and Brownson (2017) have addressed this significant gap in Hardy studies, with Ray discussing the final, volume form of the short stories and the others focusing on the initial, periodical versions. Although today most readers remain unaware of Hardy's short fiction (with the possible exception of "The Three Strangers"), he wrote nearly fifty short stories between 1878 and 1900, producing tales and novellas which straddle the dividing line between the Victorian and the modern short story. During the time that he was writing the Wessex Novels, largely for serial publication, he was also producing short fiction for the same kind of mass-market publications, the "periodicals in both Britain and America whose editors had what Harold Orel calls 'a substantial need to fill columns of white space with agreeable reading-matter' (1-2)" (cited in Schaefer and Brownson, p. 2). The four collections that he published during his lifetime contain refined versions of the periodical texts, but the four anthologies do not show present-day readers the original periodical illustrations.

Hardy, who today is remembered chiefly as novelist and poet, also wrote a total of fifty-three short stories, thirty-seven of which he published in four volumes: Wessex Tales (six short stories written between 1879 and 1888), A Group of Noble Dames (ten short stories written between 1878 and 1890), Life's Little Ironies, and A Changed Man (twelve short stories written between 1881 and 1900). As of 2017, there are just four volumes of critical work devoted exclusively to this substantial body of work: Brady's The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy: Tales of Past and Present (1982, which covers the thirty-three stories in the first three anthologies, and seventeen further stories), Ray's Thomas Hardy: A Textual Study of the Short Stories (1997, which covers all four collections and forty-five stories), Gilmartin and Mengham's Thomas Hardy's Shorter Fiction: A Critical Study (2007), which offeres in-depth analyses of a few selected stories, and Schaefer and Brownson's Thomas Hardy's Short Stories: New Perspectives (2017, which covers 47 stories in varying degrees). Each has its own focus, and reflects a growing respect for Hardy's artistry in short fiction — and a growing awareness of the circumstances of their initial publication. Of the four volumes of criticism, only the most recent both includes some consideration of the magazine illustrations and places value on the original periodical texts that reached a far greater readership than the four short story collections that Hardy published between 1888 and 1913. Brady notes that after Hardy achieved a certain financial independence from publishing novels serially, he felt less constrained by popular taste in crafting his later short fiction. However, she defends her examining the short stories in the context of the anthologies, notably Wessex Tales, which in her preface she styles "single fictional works," arguing that Hardy's

productivity in the form increased as he felt more free to write what he pleased after he had established himself, professionally and financially, as a novelist. Many of the best stories are products of his maturity and the careful organization of the short-story volumes especially demonstrates Hardy's own awareness of the themes and techniques that draw together his otherwise different narratives. The collections are themselves single fictional works. The aim of this study is to examine Hardy's short fiction in close detail in an attempt to understand his developing conception of the short story as a literary form. [p. ix]

Brady, who has examined the thematic patterns within each of the first three volumes of short stories, therefore has thought more about the associations of the stories in each volume than the periodical context in which any given story first appeared. Thus, she has not grappled with the contemporary context of a short story such as "The Son's Veto" in the way that writers in the 2017 volume do. Moreover, Brady failed to consider the significance of original periodical illustrations. However, like the contributors to the Schaefer-Brownson volume she has considered Hardy's evolution as a writer of short fiction, even as she argues for a single issue or theme that connects all of the stories in each of the anthologies:

There is discernible not only a particular kind of subject matter but also a correspondingly distinct narrative perspective which gives to the volume its own coherence and integrity. . . . three descriptive terms to designate the forms that emerge from these different narrative perspectives: a specifically regional voice informs the 'pastoral histories' of Wessex Tales; the narrowly subjective view of the Wessex Field and Antiquarian Club makes it possible to think of their stories in A Group of Noble Dames as 'ambivalent exempla'; and the ironic stance of the voice in Life's Little Ironies turns ostensibly farcical situations into 'tragedies of circumstance'. [p. x]

Although over the course of his career as a professional writer Hardy published a significant body of short fiction in such wide-circulation British and American periodicals as Harper's New Monthly Magazine, The Illustrated London News, and the London Graphic, these pieces of short fiction, including novellas and framed tales, received little critical attention until Brady's Short Stories of Thomas Hard. The contributors to the Schaefer and Brownson volume in Routledge's "Nineteenth Century" series have addressed the gap which Brady left in a series of essays that consider such matters as initial periodical publication, "gender and community relationships, and narrative techniques" ("Foreword"). They reveal how Hardy as a writer of fiction bridges the Victorian and modern periods, that is, between the traditional tale and the twentieth-century short story. In contrast, like Brady, Ray in his 1997 analysis of the short fiction of Thomas Hardy moved through his subject by the titles of the volume chronologically — Wessex Tales, A Group of Noble Dames, Life's Little Ironies, and A Changed Man and Other Tales. Thus, Ray, too, elected to use a four-part structure that followed the anthologized publication of the short stories, from the earliest collection in 1888 to the last in 1913.

In the 2007 volume of criticism published by Edinburgh University Press, Gilmartin and Mengham used Brady's organization principles, examining Hardy's fiction according to the grouping of the stories in the four anthologies. Utilizing a thematic treatment that enabled them to include several close readings of a small number of key stories, they had two major concerns: the background of social and political unrest in nineteenth-century Dorset, and Hardy's "near-obsession in his mature phase with the marriage contract" (, book blurb). They acknowledge the significance of the formal choices that periodicals such as Blackwood's Magazine forced Hardy "to encode in fiction." However, their organisation once again relies upon an anthology-by-anthology analysis. The third chapter, on Life's Little Ironies, for example, discusses legacies in terms of gender politics: "the failure of nineteenth-century men and women to settle on a creative and meaningful relationship with the past and the future." The final chapter, however, provides in-depth analyses of several stories about which the volumes by Brady, Schaefer and Brownson have said little. Gilmartin and Mengham, for example, discuss "A Tryst at an Ancient Earthwork" (1885) in terms of Hardy's handling of the themes of "historical retrieval and the ethos of keeping faith with the past." They have also examined several stories in this chapter which neither the 1882 nor the 2017 volumes have covered in any detail, namely "The Duke's Reappearance" (1896) and "Enter a Dragoon" (December 1900 — the last short story that Hardy published in a periodical). However, the 2007 volume does not consider the periodical context of the stories in as thorough a manner as Shaefer, Brownson, and their eight collaborators.

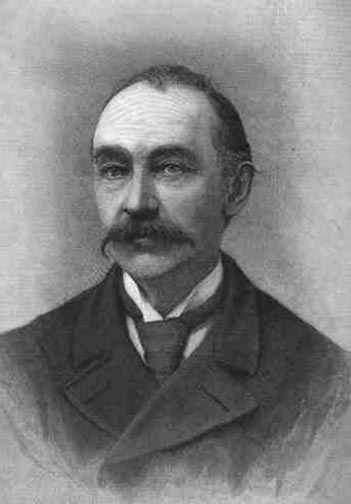

Mr. Thomas Hardy, The Novelist, aged 52 in The Illustrated London News (1 October 1892).

Even during the period in which he presented himself to the reading public largely as a writer of short fiction, advertisements in the periodicals for which he wrote described him as a late Victorian sage and novelist, probably because the novel had far more artistic caché than the short story. In ten chapters, the writers span Hardy's production in the "lesser" genre, from A Group of Noble Dames in 1890 to "A Changed Man" and Other Tales in January 1913.

Ray began his bibliographical study with a detailed description of the collection entitled Wessex Tales (1888) and concluded with A Changed Man and Other Tales (1913). Since the oldest story within that first anthology, "The Distracted Preacher," predates the publication of the anthology in which it finally appeared by nine years, such an overall organisational strategy implies that Ray was thinking in terms of Hardy's short story writing as occurring within a twenty-five-year period (1888-1913). In fact, Hardy wrote short fiction from 1865, when his first published work, "How I Built Myself a House" (in Chambers's Journal, 18 March, 1865),until "Enter a Dragoon" (in Harper's Monthly Magazine, December 1900) and "A Changed Man" (in The Sphere, 21 April 1900), a span of thirty-five years, a period longer than the twenty-five years in which he wrote the Wessex Novels.

Hardy's Re-thinking The Christmas Story: "What the Shepherd Saw, A Tale of Four Moonlight Nights," The Illustrated London News (5 December 1881)

The new book offers the advantage over Ray's and Brady's discussions of Hardy's short fiction in that it presents ten different perspectives, all of which are current in terms of the historicist and feminist analyses of short fiction (hence, the book's subtitle "New Perspectives"). The first section, "Periodical Publication," presents Graham Law's study of the periodical forms of the stories that would be grouped as A Group of Noble Dames, from the outset a framed tale. In the second chapter, Brownson examines how Hardy responded to the subgenre of the traditional Christmas story, which had been a staple of Victorian periodicals in their annual Christmas Numbers for thirty years when Hardy published "What the Shepherd Saw" in The Illustrated London News on 5 December 1881. Her consideration of the story in the context of its serial publication is quite different from Ray's examining it within the context of the later stories collected in "A Changed Man" and Other Tales (1913), which includes short stories that Hardy wrote over twenty years. Of these twelve tales, although the order of the components does not so indicate, "What the Shepherd Saw" is the earliest. Ray has devoted a single paragraph to the serial text versus the manuscript as he graphs the evolution of the story from its mass-publication form of 1881 to its final, volume-form:

The serial gives a slightly greater definition to the opening's topography. The location of the scene on a spot near the turnpike road from Casterbridge 'before you come to Melchester' is a little more specific than the MS., where the quoted phrase is not present. The serial's first two references to the name of the ruin being the Devil's Door are also absent from the MS. The only substantial alteration for ILN is the addition of eight lines in the second paragraph describing how the clump of furze was hollow and the hut was thus completely screened and almost invisible ('with enormous stalks [...] In the rear'). This alteration permits the later substitution of the MS.'s reference to 'the hut & trilithon' (fo. 3) by the serial's 'the trilithon and furze clump that screened the hut'. [Ray, p. 303]

As a bibliographer, Ray immediately reveals his interest in the story's evolution from serial to volume form, but his point of reference is always the latter. Perhaps privileging volume publication himself, Hardy "did not possess even a copy of the periodical publication" in August 1913 when he was finalising material for A Changed Man and Other Tales; in fact, he had to apply to his publisher, Maurice Macmillan, for a type-script made from the ILN's periodical version. Hardy made a number of obvious changes, including the names of the murdered lover ("Fred Pentridge" becomes "Fred Ogbourne") and the young shepherd ("Bill Wills" becomes "Bill Mills"), but these place-oriented names in the original text merely reflect the locale near Wimborne where Hardy was living when he wrote the story — "Pentridge," for example, comes from an actual village in nearby Cranborne Chase. Throughout his discussion, Ray has used the volume form as his base text as he was concerned with the writer's final intentions. In contrast, Brownson has examined the serial texts of "What the Shepherd Saw" and "The Son's Veto" (ILN 1 December 1891) for their implications about Hardy's increasing understanding of his broad periodical readership and his development as a writer:

These two stories exemplify the impact of periodical publication on Hardy's growth as a short fiction practitioner. In constant need of text to fill the pages of their publications, editors in their haste to print a finished product often overlooked some of Hardy's innovative approaches. This never-ending requirement for text allowed Hardy to experiment with content, theme, and form in the genre, experimentation that has had lasting implications for the short story form well into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. These two short stories highlight not only the attitudes of late Victorian periodical authors, readers, and editors toward "the Christmas stort," but also Hardy's negotiation with Victorian periodical culture and its effect on his short story output. [p. 31]

Issues of Gender and Class Reflected in the Text and Illustrations of "The Son's Veto," The Illustrated London News (December 1891)

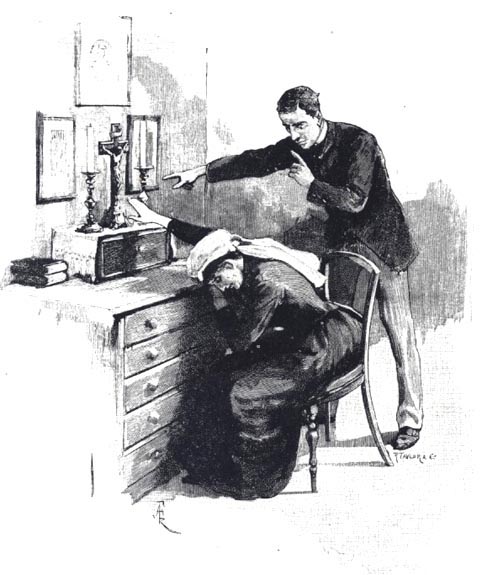

Brownson's critical approach enables her to discuss within a single chapter two rather different stories written ten years apart for the mass-market, densely pictorial Illustrated London News whose editor, Clement Short, made editorial decisions based on the changing tastes and attitudes in the broad Victorian readership. Ironically, despite its narrative sophistication and exploration of class tensions (peasant versus aristocrat, subservience versus privilege), "What the Shepherd Saw" betrays its belonging to oral, folklore tradition with a rural backdrop and at least a nod to the conventional seasonal setting, whereas "The Son's Veto" has an urban backdrop and contemporary setting for its consideration of protofeminist social issues. Moreover, unlike the 1881 Christmas offering, the later story of male domination was accompanied by two large-scale lithographs by Alfred Forestier that bracketed the story: Ned came and stood under her window and He made her swear before a little cross and shrine in his bed-room that she would not wed Edward Hobson without his consent, pages 21 and 25 (1 December 1891). Brownson argues that Hardy deliberately challenged the conventions of the Christmas Story in the "The Son's Veto." For example, although he is a minister, the son in this story behaves in a consistently self-centred, unChristlike manner:

Randolph Twycott, now grown and soon to be ordained, finally forces his mother to swear, at Easter before the Christian altar in his bedroom, that she will never marry Ned Hobson [his mother's former love, a market-gardener who routinely brings produce up to London] without his consent. "The Son's Veto" is another of Hardy's titles in a periodical's Christmas number which masks the grimness of the story's events. Hardy could easily have entitled the work "A Son's Veto," but his use of the definite article calls attention to "The Son" Most likely on readers' minds at the Christmas season. That Randolph Twycott would exact such a cruel promise at Eastertime recalls with scathing irony the devotion of Christ's mother to her son in Hardy's story, an earthly representative of Christ's filial devotion, negates his mother's emotional and physical being — her disappointment and resulting solitude cause her to die four years later — confirms as well Hardy's growing rejection of the institution of the Church, what Harold Orel calls "his anger toward the smug and hypocritical clergy" (114). [Brownson 43]

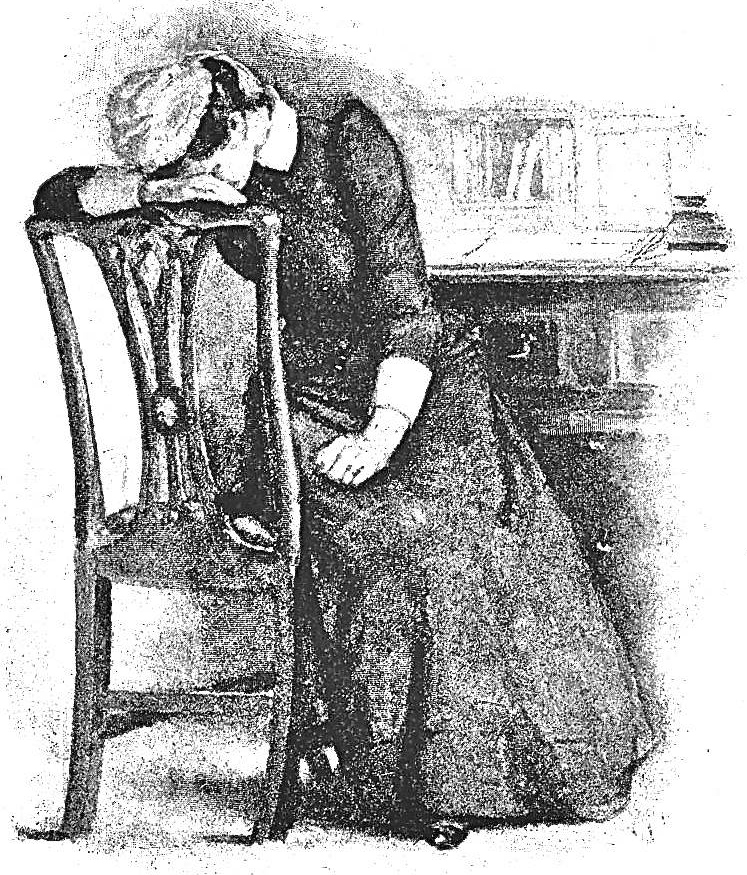

Although Brownson has reproduced the second of the two Forestier illustrations (the first, showing Sophy and the market-gardener, Ned, in conversation at her window, occurs later in the book), she makes no use of it in her argument that Hardy exploits urban-rural, gender, and class anxieties in "The Son's Veto"; without comment, however, it ably demonstrates how the child has grown up to become his mother's keeper — in fact, her jailer. Brownson, nevertheless, makes no reference to the telling illustration which encapsulates "the son's veto," even though she has placed it on the very page on which she contends that the Illustrated London News situated Hardy's story in the seasonal number that contained much more conventional Yuletide fare — including Arthur Quiller-Couch's "A Haunted Dragoon" and Bret Harte's "Their Uncle Tom from California." The Hardy story has none of the gothic, romantic, or action story content typical of the ILN's Christmas numbers in the fin de siécle. In its gender politics and ingratitude of the egocentric, class-conscious child "The Son's Veto" "opens up new possibilities for modernist short story artists such as Joseph Conrad and Katherine Mansfield" (45).

The Significance of Letters and Letter-writing in "On the Western Circuit," in The English Illustrated Magazine (December 1891)

Whereas Brady devoted nineteen of the two hundred pages in The Short Stories of Thomas Hardy: Tales of Past and Present to "On the Western Circuit" (1900), Schaeffer and Brownson devote thirty-three pages of their book to the same story. The difference in the volume of discussion reflects differences in interpretation. Brady sees the story about sex and marriage as another vehicle for "irony of circumstance with irony of form" (120), the short fiction equivalent of the "well-made play" as revised by George Bernard Shaw and Heinrich Ibsen: "in Hardy's story the reader's sympathies are constantly in tension with the laughter which the plot elicits" (120), like the experimental dramatists linking the farce of the well-made play with the serious consequences of those comic situations in the characters' lives. Hardy makes the story almost anecdotal, using conventional short story characterization, plot, and language. However, Hardy makes the story with a conventional form a vehicle for an unconventional theme, which Brady articulates as “the inability of men and women when making sexual choices to act with full self-knowledge and without deception toward each other — and the resulting inadequacy of the legal contracts which give formal expression to these choices” (127). Brady, however, fails to consider either the periodical origins of the story, or the implications of the various letters, not merely as structural devices and sources of irony, but as extensions of the letter-writers themselves. She examines the story briefly in the context of the volume in which it appeared, Life's Little Ironies (1894), but only mentions in her "Notes" the periodicals in which it appeared three years earlier. The latest of study of the story in the Schaefer and Brownson volume foregrounds the issue of Hardy's use of letters as narrative devices, according to the conventions which Samuel Richardson established in the epistolary novel Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded (1740).

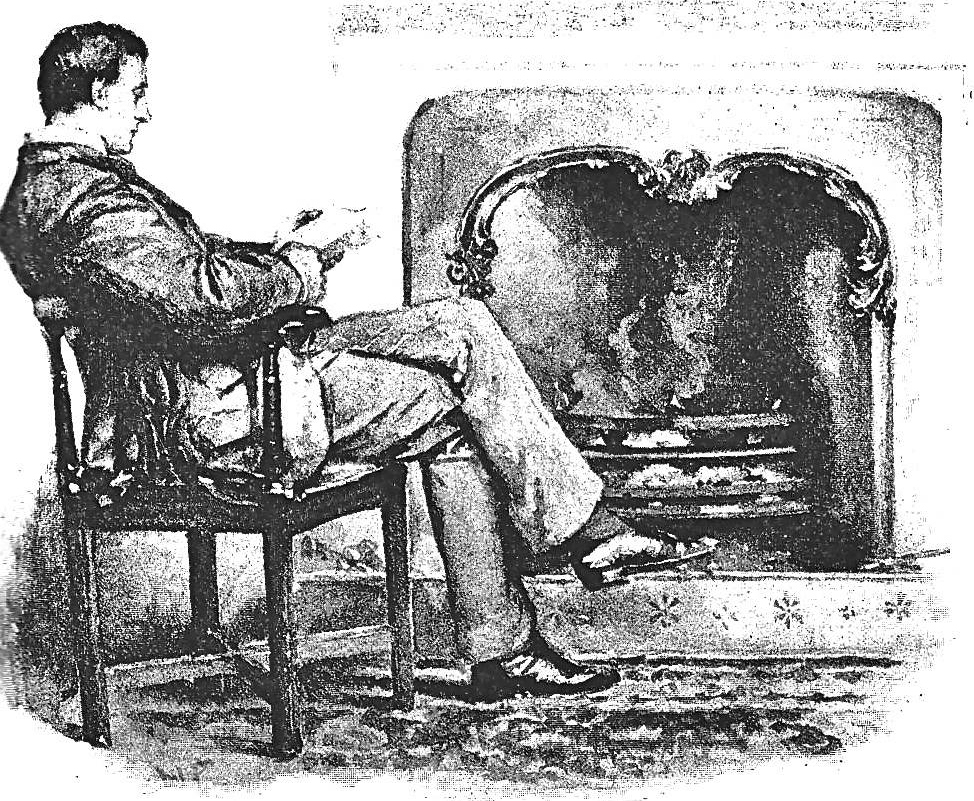

Of the set of four lithographic illustrations by Wal Paget that originally appeared with the Hardy story in The English Illustrated Magazine, editors Schaefer and Brownson reproduce only the two most germane to letter-writing: "It was a most charming little epistle" in Chapter 3 (p. 58), which focuses on Charles Raye's reception of Anna's (in truth, Edith's) letters, and "'I wish he was mine!' she murmured" in Chapter 5 (p. 89), so that these illustrations complement the analyses of the story by two different writers, Suzanne J. Flynn and Karin Koehler. Although she is the recipient of a letter from lawyer Charles Raye in the opening illustration for the story, in neither illustration reproduced in this book does the maid, Anna, appear directly; however, both Paget periodical illustrations reproduced reference her relationship with her mistress and amanuensis, and with her seducer. The former illustration depicts the lawyer in his London rooms perusing what he believes is one of Anna's early letters, the latter a woman trying to restrain her tears at her unfulfilled longing for Raye. In this second illustration, the reader can easily mistake the respectable matron, Edith Harnham, for her young maid because the figure is dressed in black, the face is not visible, and her cap looks like a maid's.

Indeed, although the critic does not comment upon the significance of any of the illustrations from The English Illustrated Magazine, Paget may well be deliberately creating the ambiguity to imply that, during their correspondence with Raye, the two women become extensions of each other as the London lawyer is wooing the maid via letter, but in turn is being led on in thoughts of marriage by the girl's infatuated mistress. Significantly, the figure in this anguished pose sits before a writing desk. The accompanying text explicates the meaning of each illustration. In the earlier illustration, involving Raye as the reader, the lawyer, unaware of the true identity of his correspondent, ironically assumes he is writing to the sweet country girl whom he has seduced in just two days at Melchester. Hardy renders plausible the relationship between the upper-middle-class Londoner and the illiterate girl from a remote village on Salisbury Plain by means of the social context of letter-writing. Owing to the development of the Penny Post, the young man and young woman from vastly different positions socially and geographically can conduct a romantic discourse. The Londoner, unfamiliar with the state of rural Dorset, anticipates that, owing to the National Schools, Anna is fully literate and quite capable of conducting such an amatory correspondence. Such a level of literacy even in one from so humble a station the periodical reader would have expected. In fact, utilizing Anna's lower class remote rural origins, Hardy has taken pains to account for Anna's inability to read and write:

This young woman, he explains, has slipped through the system of national education because she "had grown up under the care of an aunt by marriage, at one of the lonely hamlets on the Great Mid-Wessex Plain where, even in the days of national education, there had been no school within a distance of two miles. . . . (465). As this clarification suggests, Anna's illiteracy would have been perceived as an anomaly, even by contemporary readers. [Koehler, p. 87-88]

Although Raye reasonably expects that Anna can carry on some desultory form of correspondence, he is surprised by the calibre of her ideas as opposed to the simple form of expression, even if the quality of her stationery and its colour ("linguistic and material signifiers of lower-class status," remarks Koehler) do not undermine the illusion that his correspondent is indeed the young maid from a provincial town, like the protagonist in Samuel Richardson's epistolary novel Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740):

Like Richardson's Pamela, Hardy's Anna wins a man's love through letters, letters which are especially appealing due to a "free" and "natural" style of writing. But, unlike Pamela, she cannot even decipher her own name on an envelope handed to her by the postman. It is her complete illiteracy which constitutes the foundation for Hardy's incisive critique of the notion that letters between lovers are "the spontaneous renderings of a person's innermost thoughts" (Perry, Women 76). [Koehler, p. 88]

Even though in the 1890s Hardy had to be careful about such issues as pre-marital and extra-marital sex, Bowdlerization did not cause him much trouble in this story since so much of the developing relationship is in the correspondents' reactions to each others' letters. In "'Getting Life Leased at Any Cost' — Marriage in Hardy's Late Short Stories," Suzanne J. Flynn examines "On the Western Circuit" in the context of late Victorian readers' attitudes towards romance, courtship, and marriage as the stuff of magazine fiction. She points out that a number of Hardy's heroines are not mere ingénues entering marriage as young women: Sophy Twycott in "The Son's Veto" is a widow hoping for a second marriage; Leonora Frankland in "For Conscience' Sake" is the grey-haired mother of a young woman of marriageable age; Ella Marchill, the Imaginative Woman in the story of that title is the thirty-year-old mother of three; and in "On the Western Circuit," although she has no children, Edith Harnham, too, has arrived at the age of thirty and therefore should possess mature judgment. And all three heroines express dissatisfaction with the lives, Edith because, having married a complacent wine merchant much older than herself, she feels lonely, despite her social status and comfortable life style. In terms of one of the story's most repeated terms, Edith has made a "contract" for life, and feels compelled to abide by it, despite her unmet romantic yearnings. These she realizes imaginatively or vicariously by generating amorous texts on behalf of her illiterate maid, Anna, whom she thinks of as a sort of surrogate daughter whom she must protect by seeing her well married:

Once she learns of Anna's seduction, her fatalistic stance — "what was done could not be undone" (466) — gives her licence to satisfy her own deeply felt, unmet needs through her correspondence with Raye. These needs are complex; the "deeper nature" that her marriage leaves unstirred involves emotional, maternal, and erotic longings. The frisson of pleasure she experiences when Raye slips his fingers into her glove (believing the glove to be Anna's) reveals the level of her sexual hunger. [Flynn, 58]

Thus, Hardy's choosing a mature woman as his principal protagonist and making the maid, Anna, and the young lawyer, Raye, her antagonists enables the fin-de-séecle writer to explore elements of female sexuality which earlier popular British authors rarely dared to plumb. According to Karin Koehler’s"'Imaginative Sentiment' — Love, Letters, and Literacy in Thomas Hardy's Short Fiction," Hardy manipulates letters "to subvert the epistolary paradigm first popularized by Pamela — dismantling customary assumptions about the letter as a form of emotional expression and mode of interpersonal communication — in order to expose the artificiality of a prevailing cultural narrative that equates marriage with romantic love, and romantic love with desire" (Koehler 85). Hardy's focus should be familiar to readers of Flaubert and Tolstoy: the frustration of a mature heroine trapped in an uncongenial marriage, which Hardy's Edith Harnham regards in legal terms as "a contract for life." Ironically, the expert in making and breaking legally binding contracts, Charles Bradford Raye, falls into such an unsuitable contract himself when, acting upon a false assumption about the author of the correspondence, he marries the uneducated maid.

Raye should have reflected that the young woman whom he had known two days could not possibly have composed gripping letters with a free and natural style. Through theirdignified and self-possessed tone the letters have won him body and soul. Only after the marriage does Raye learn the complete truth, too late realising that he is in love with letter-writer Edith rather than the physical Anna. Koehler notes that Hardy exploits letter-writing for its ironic value in two other love stories involving in imbalance in social status and three principals, "The Melancholy Hussar of the German Legion" and "A Mere Interlude." These stories about disappointed, unfulfilled middle-class heroines parallel the situations in two foreign novels with which Hardy was undoubtedly familiar in translation: Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (1878) and Flaubert's Madame Bovary (1856). Thus, Flynn and Koehler associate Hardy with the intellectual life of the fin-de-siécle in a manner very different from Brady's relating "On the Western Circuit" to the drama of Shaw and Ibsen.

Other relevant illustrations from The English Illustrated Magazine

Left: The postman calls upon Anna with a letter she cannot read, "'It is mine,' she said.". Right: Charles Raye too late realizes that he fell in love with Edith Harnham, not her maid, "'I think I have one claim upon you.'" (December 1891). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Hardy's Handling of Mystery and Gothic Conventions in "The Three Strangers" and "The Withered Arm"

Since writing this story some years ago I have been reminded by an aged friend who knew 'Rhoda Brook' that, in relating her dream, my forgetfulness has weakened the facts out of which the tale grew. In reality it was while lying down on a hot afternoon that the incubus oppressed her and she flung it off, with the results upon the body of the original as described. To my mind the occurrence of such a vision in the daytime is more impressive than if it had happened in a midnight dream. Readers are therefore asked to correct the misrelation, which affords an instance of how our imperfect memories insensibly formalize the fresh originality of living fact — from whose shape they slowly depart, as machine-made castings depart by degrees from the sharp hand-work of the mould. — Thomas Hardy, "Preface" to Wessex Tales, April 1896.

Neelanjana Basu, the author of the critical essay on Hardy's use of (indeed, one should say "manipulation of") the omniscient point of view in the tale of the supernatural, "The Withered Arm," and the mystery "The Three Strangers," contends that the tale-teller's exercising his prerogative for "misrelation" is the key to understanding Hardy's handling of narrative point-of-view. In each of these exemplary "Wessex Tales" the narrator is only apparently using the conventional omniscient:

On the one hand, in "The Three Strangers" Hardy interweaves supernatural elements into a tale of detection, thus releasing a wealth of false and true clues, and problematizing the process of interpretation. On the other hand, Hardy's "The Withered Arm" — a supernatural tale of folk superstition — exploits the narrative techniques of classical detective fiction in presenting a fragmented story composed of half-suggestions. But if generic ambivalence subverts any anticipation of formulaic resolution on the part of the reader, it also allows interpretive freedom by loosening the regulative control of generic codes. Consequently, the act of reading acquires the nature of an interpretive adventure. ["'To correct the misrelation': Reading Hardy's Wessex Tales, p. 145]

The first uniform edition of Wessex Tales in the single-volume Osgood, McIlvaine edition of 1896 contains just six stories:

"An Imaginative Woman" (1894) [transferred to Life's Little

Ironies in 1912]

"The Three Strangers" (1883)

"The Withered Arm" (1888)

"Fellow-Townsmen" (1880)

"Interlopers at the Knap" (1884)

"The Distracted Preacher" (1879)

Hardy later moved the first of these to another anthology, and added both "The Melancholy Hussar of the German Legion"(1890) and "A Tradition of Eighteen Hundred Four" (1882), which give historical depth to the Wessex setting. Thus, precisely which stories constitute the Wessex Tales is problematic, although as of 1912 Hardy finally intended that the collection include seven stories in a single volume. Circumventing this bibliographical issue, Basahas chosen to analyze the two best-known, most anthologized, and most representative of the Hardyesque folktales or "Pastoral Histories" (Brady, p. 1) in every volume entitled Wessex Tales: Strange, Lively, and Commonplace published since 4 May 1888 (a two-volume set which contains only five stories). As Brady notes of the class-orientation and cultural backgrounds of the stories,

Wessex Tales reflects in its narrative details the social, economic, and cultural diversity of Dorset life. Within a narrow range (no aristocrats or gentry are presented), a complex hierarchy is portrayed, from the shepherds and artisans of "The Three Strangers" to the relatively wealthy tradesmen of "Fellow-Townsmen" and "Interlopers at the Knap." Most of the places described in the volume have factual counterparts in Dorset. ["'Wessex Tales': Pastoral Histories," p. 2]

The stories, then, encompass Hardy's home country and social class; as a writer he claimed kinship with, and best understood, these kinds of rural characters. Consequently, in using the omniscient point of view he found it easy to enter into and assess the consciousnesses of characters such as Timothy Summers, Shepherd and Shepherdess Fennel, Phyllis Grove, and Rhoda Brook. However, in such stories as "The Melancholy Hussar of the German Legion"and "A Tradition of Eighteen Hundred Four" (notably late additions to the collection) Hardy "draws the reader into a place and time foreign to his own experience" (Brady, p. 16). One tends not to detect any problems with historical authenticity, however, because Hardy's all-knowing narrator possesses a profound sense of both the individual psychology and the nature of the events that shape each tale. As an omniscient narrator in such stories as "The Withered Arm" and "The Three Strangers" which require the reader to be alert to salient details in order to solve a mystery, Hardy revels in offering up red herrings and misdirections, leading to misreadings of intentions and identities both for the characters and the readers. Basu in "'To correct the misrelation': Reading Hardy's Wessex Tales explores such elements, rather than the historical or sociological background, which Brady has already ably canvassed. For example, Basu regards certain characters as standing in for detectives engaging in the same "writerly" activities which Hardy forces his readers to undertake in order to resolve a details into a solution to a mystery. However, as Basu points out, these curious characters thus engaged prove at best to be flawed detectives who cannot escape their own false assumptions:

Like the truth-seekers in "The Three Strangers," Rhoda Brook in "The Withered Arm" is misled by ideology when she claims to have reconstructed a meaningful story out of disconnected events. When the two women come face to face over the dead body of Rhoda's son in the country prison, Rhoda identifies Gertrude, the wife of her child's father, as the witch who has "overlooked" (that is, cast an evil eye upon) her life. Rhoda's confident misreading of the "meaning" of her dream results from her internalization of patriarchal ideology. [151]

Basu describes Hardy's individualisation of the omniscient in "The Withered Arm" as "narrative focalization" (154), by which she means Hardy has divided his "omniscience" into a number of "shifting perspectives of various characters and voices, each giving scattered information regarding the story" (154). However, strictly speaking, one cannot classify these shifting perspectives as limited omniscient because Hardy elects to confer no special credence or objectivity to any them. Rather, he remains aloof and denies the superiority of any character's perspective. Also, he fractures the narrative perspective of "The Withered Arm" "by deliberate omission of information at the most significant moments in the narrative, inconsistency and narrative focalization" (153). Both the protagonist and the antagonist, Rhoda and Gertrude, for example, have dream-visions which Hardy narrates from their perspectives; however, he undercuts the reader's believing in them by such expressions as "if her assertion that she really saw, before falling asleep, was not to be believed" — Basu notes that Hardy did nothing to eliminate the ambivalence by altering "if" in the original text in Blackwood's Magazine to "since" in later editions. And the collective wisdom of the community, which is just as likely collective imperceptiveness, of "they" and "them" (as in Gertrude's servants), remains merely an unsubstantiated opinion.

Basu contends that the key questions which Hardy leaves unresolved in these stories are "Who is a criminal?" (in the case of "The Three Strangers") and "Who is a witch?" (in "The Withered Arm"); she might have reformulated these as "What forces conspire to make a perfectly ordinary member of the middle-class commit a criminal act?" and "Can we attribute the majority of unfortunate occurrences in lives simply to evil persons?" "By foregrounding the acts of misreading in which the reader is implicated by virtue of reading the story, Hardy draws the reader's attention to "misrelations" in signification that become part of naturalized discourses" (155). Thus, asserts Basu, these stories are not primarily about crime or witchcraft in a rural community, but about the reader's "interpretive failure" to arrange the clues into a satisfactory narrative that takes all features of that narrative into account. In engaging "writerly" activities, as each of these stories from Wessex Tales seem to require of the reader in order to fill in gaps in the plot and furnish suitable motivations, the reader fails in his or her function as a careful interpreter of clues.

Problems of Modernity in a Tale of the Supernatural: "The Fiddler of the Reels"

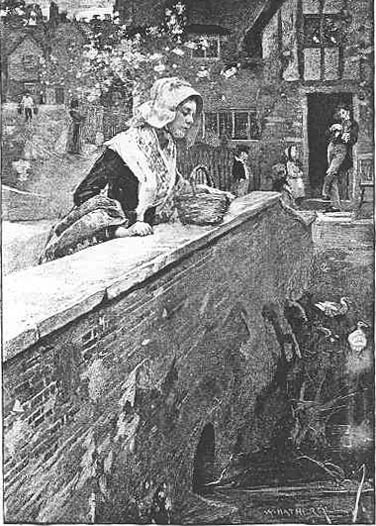

In "Representations of the Body in Hardy's Life's Little Ironies (1894), Carolina Paganine examines several stories in Hardy's second anthology: "The Son's Veto," "An Imaginative Woman," "On the Western Circuit," and (with an appropriate illustration — She chanced to pause on the bridge near his house to rest herself — from the story's initial appearance, in Scribner's Magazine for May 1893) "The Fiddler of the Reels." In all of these stories about the problems of modernity, Hardy challenges the rational ethos of the period, and thereby would have appealed to the tastes and predispositions of more sophisticated readers. Paganine suggests that

the metaphorical rendering of the body represents a modern aspect of Hardy's prose, going against the age's predominant trend of positivism and rationalism which believed there was a distinct separation between mind and body, or between emotions and reason. Hardy's representation of the body appears to be an attempt to blur the limits between those categories, as he closely relates descriptions of the body to the characters' feelings and psychological state of mind. [p. 160]

Paganine's analysis unfortunately makes little use of the chapter's other illustrations, the Hatherell lithograph, which the author or the editors have strategically inserted into the chapter. This lithograph supports her contention that "the story narrates how music exercises a somewhat magical power over the body of Car'line Aspent" (p. 171), although the illustrator pushes the antagonist, the demonic outsider Mop Oliver, the fiddler of the story's title, well into the background in order to present the protagonist's dreamy (rather than physical) response to the music. As Pagaine notes, Hardy gives the violin an almost human voice ("a certain lingual character") that can "touch" not merely the ear but the whole body of the enraptured listener: "This association anticipates and stresses the sensual effect that the music incites on the person of Car'line and especially on her body" (p. 171). Mop's music does not operate as a date-rape drug in that she experiences negative sensations ("discomfort, nay, positive pain, and ultimate injury") while under its influence. The fiddle music compels her to dance, leading her into convulsions suggestive of a sexuality that Hardy describes in terms of a fever or a disease: it "would require a neurologist to fully explain," remarks Hardy's narrator, connecting the supernatural dimension of the violin music with a topical branch of modern medicine. If Car'line is entrapped, neither the music alone nor the outlandish Mop of the hypnotic eye ensnares her; rather, the girl's own emotional makeup, her yearning for such release as Mop provides, catches her up, enabling her unconsciously to express her sexuality through her physical and psychological responses. Thus, Paganine connects this particularly story of possession to the larger body of Hardy's work:

In Hardy's stories, the connection between the exterior and the interior selves happens with symbolic and metaophorical representations of the body and with the perceptual and sensuous impressions they leave behind, provoking multiple reinterpretations, not only of the characters themselves, but also of the stories' fictional re-description of reality and narrative. [pp. 174-75]

Mop operates not merely outside Car'line's previous experience, but outside the community's as well. Mop's overt sexuality, which his unruly hair exemplifie and which his nickname signifies, reveals that "he is a character who does not conform to Wessex mores and exercises his freedom, as he does not play religious melodies, almost an obligation for all musicians at that time, and has no fixed address, profession, or woman" (p. 173). An exotic import, Mop transgresses the traditional sexual and cultural boundaries of the rural community, and in doing so undermines its values.

Metalepsis and the Shifting Narration in Hardy's Last Story, "A Changed Man" (1900)

The protagonist of the last story which the volume examines, "A Changed Man," breaks the boundaries of his established, rakish character, and undergoes a genuine spiritual conversion that leads him from an egocentric self-gratification of bodily appetites to altruistic self-sacrifice and, ultimately, self-destruction. Keith Callis in "Hardy's Mercurial Narrator: 'Breaking the frame' in 'A Changed Man'" (1900: fittingly, the last short story that Hardy wrote) focuses, however, not so much on the mercurial Jack Maumbry, an officer in the Hussars and then a preacher, as on the mercurial narrative voice and its connection with the observant invalid in the oriel window.

At the conclusion of The Return of the Native, as Callis notes, Hardy apparently cannot decide between having Thomasin remain a widow (a realistic turn) or marry the enigmatic Diggory Venn (the conventional happy ending): "Readers can therefore choose between the endings, and those with an austere artistic code can assume the more consistent one to be the true one" (Book Sixth, ch. III). This subjective intervention rather than a narratorial musing suggests that Hardy as a writer attuned to the tastes of the reading public concluded that the "realistic" conclusion would strike the majority of his readers as too "austere" and therefore as emotionally unsatisfying. Now, in this late short story, "A Changed Man," Hardy once again had to decide whether an austere and the realistic conclusion is suitable for the tale of Captain Jack Maumbry, whose initial identity as an elegantly dressed, beautifully mustachioed cavalry officer in full dress uniform the first illustration, "There is a good deal in Sainway's argument about having no band on Sunday" in The Sphere (21 April 1900, p. 419) underscores. Unfortunately, neither the before- or the after-conversion illustration appears in this chapter, despite the fact that each represents, as it were, a contrary trajectory for the story. The title of the essay points not merely to the musings of Hardy's mercurial narrator, but to "metalepsis," which Collis defines as a break resulting from the narrator's intruding upon the world being narrated, so that the omniscient or limited omniscient narrator begins to interact directly with the events being narrated. In "A Changed Man," the "metaleptic breaks in the story frame occur as Hardy considers alternatives, attempted negotiations between lyrical and tragic turns of plot, and conclusions consistent with them" (p. 177). Perhaps another way of thinking about Hardy's "metalepsis", contends Collis, is that Hardy's use of the narratorial intervention in "A Changed Man" "differs in kind and complexity from such earlier instances" (p. 178) as Charles Dickens's in chapter 38 of Nicholas Nickleby and George Eliot's in the first chapter of The Mill on the Floss:

It offers a shrewd and fascinating use of metalepsis, subtle feats of narrative craft in which the controlling intelligence(s) both are and are not in the "present" of the telling, in which he, she, or they cross narrative levels from the framing narrative to the central story and go back again, sometimes occupying both at once. Sometimes the narrative voice inhabits multiple levels, and sometimes it dissolves into thin air between the reader and the page, like social customs that disappear during long arcs of historical change." [p. 179]

In the golden age of commercial magazine fiction at the close of the nineteenth century, most readers demanded both realism and conventional closure; in other words, they wanted, simultaneously, art and entertainment. Consequently, in "A Changed Man" Hardy realised that merely telling an engaging story would not meet critical readers' expectations "for subtle responses to the sense of dislocation and drift many felt at the end of the nineteenth century" (p. 179). The radical changes which Jack Maumbry undergoes suggest this fin-de-siécle "drift": Hardy reflects this contemporary anxiety in the manner in which he tells Jack's story, embracing both traditional and emerging expectations of magazine fiction. Hardy's manipulation of the narrative perspective involves establishing the invalid in the oriel window at The Top o' Town in Casterbridge (Dorchester) as the principal observer and narrative voice, and then, in the last two portions of the story (sections VI and VII), replacing him with an anonymous, omniscient narrator. However, from the opening lines of the story Hardy challenges the knowledge (and therefore the judgment) of the interior narrator, the invalid: "The person who, next to the actors themselves, chanced to know most of their story" (p. 1, emphasis added). Callis notes that, in introducing the invalid, Hardy's "framing narrator breaks his frame from the start by including the invalid, and manages to de-emphasize the 'reality' of the source of the story" (p. 182), creating and then undoing the authority of the invalid as interior narrator.

The invalid from his privileged vantage point and his relationship with Laura in the first five sections incorporates a range of communal perspectives, assembling them into a coherent story from the accounts of "schoolboys," "the lawyer's son," "an old and deaf lady," "more than one townsman and woman," "young ladies to the westward," and "spectators" at the wedding. Fragmentary as these accounts may be, the invalid plays his part satisfactorily as the narrator of the internal frame. But then the astute reader begins to realize that the credibility of his sources and therefore of his account deteriorate as the reader reflects that the invalid has probably not interacted with such witnesses to later events as the patrons at the White Hart and Laura's "detractors":

one protests that these perspectives are not entirely accessible Parts VI and VII, they all very curiously disappear following Captain Jack Maumbry's conversion and are replaced by an omniscient narrator in yet another instance of the mutability of perspectives, a fact of narration delivered with irony and as something of a surprise given the subtle play of viewpoints that comes earlier. Yet in each part of the story, the mode of narration is artistically responsive to the degree of authority one might see in its source and the level of confidence it inspires. [p. 180]

As a further piece of metalepsis, the story's conclusion demonstrates that, sometimes, a writer cannot provide absolute closure. Since he has elected to employ a limited omniscient point of view at the close, Hardy cannot neatly relate the motives of the lovers, Laura Maumbry and Lieutenant Vannicock:

But whether because the obstacle had been the source of the love, or from a sense of error, and because Mrs. Maumbry bore a less attractive look as a widow than before, their feelings seemed to decline from their former incandescence to a mere tepid civility. What domestic issues supervened in Vannicock's further story the man in the oriel never knew; but Mrs. Maumbry lived and died a widow. [p. 24, emphasis added]

Hardy pointedly avoids giving his periodical readers the sort of closure which they would have expected and which most magazine fiction offered. Laura's re-marriage would have inartistically brought together the guilt-ridden wife and the slightly devious Vannicock: "One imagines Hardy behind this account — sympathetic, observant, reserved, like the invalid when he refuses to offer Laura comment on her husband's change" (p. 187). The invalid's surveillance of characters' comings and goings (as implied by the oriel window's vantage point from the Top o' Town to the fields of Durnover beyond Grey's Bridge at the bottom of the hill) involves regarding and reporting exterior facts; the invalid and, by extension, the outer narrator must merely infer Laura's motives in living and dying a widow rather than the wife of the rakish Vannicock.

Conclusions: The Effects of Periodical Publication Considered

The 2017 book of criticism complements rather than duplicates the work of earlier critics. Whereas Brady, thinking in terms of anthologies rather than the periodical origins of Hardy's short fiction, focusses on the stories in Wessex Tales, A Group of Noble dames, and Life's Little Ironies, Schaefer and Brownson utilize the modern critical perspectives of ten scholars to examine about twenty per cent of Hardy's output as a short story writer, although in passing the contributors consider works that most critics neglect, including Our Exploits at West Poley and "The Thieves Who Couldn't Stop Sneezing." Although the 200-page book canvasses nearly the entire opus, it offers more than five pages of analysis on each of just ten selections: "The Three Strangers," "The Withered Arm," "On the Western Circuit," "The Son's Veto," "What the Shepherd Saw," "An Imaginative Woman," "Destiny and a Blue Cloak," "The Fiddler of the Reels," "Fellow Townsmen," and "A Changed Man." This promotes itself as the "first edited" volume of essays dedicated to the subject of Hardy's short fiction, and it fulfills its promise of offering multiple voices and fresh critical perspectives, a number of which reflect the dual-voiced Gilmartin and Mengham analysis of Hardy's fiction as responses to societal changes at the end of the nineteenth century, including the burgeoning readership of mass-market periodicals:

This critical study of Hardy's short stories provides a thorough account of the ruling preoccupations and recurrent writing strategies of his entire corpus as well as providing detailed readings of several individual texts. It relates the formal choices imposed on Hardy as contributor to Blackwood's Magazine and other periodicals to the methods he employed to encode in fiction his troubled attitude towards the social politics of the West Country, where most of the stories are set. No previous criticism has shown how the powerful challenges to the reader mounted in Hardy's later stories reveal the complexity of his motivations during a period when he was moving progressively in the direction of exchanging fiction for poetry.[Publisher's blurb, Thomas Hardy's Shorter Fiction: A Critical Study].

The 2017 goes well beyond Gilmartin and Mengham's intention in 2007 to bring the criticism of Hardy's short fiction up to date: "this is the first edited collection devoted solely to Hardy's works of short fiction" (Routledge promotional blurb, back cover). In utilizing some challenging critical perspectives, the international team of contributors occasionally resort to critical terms such as "hypodiegetic" and "extradiegetic" (p. 181), but the average reader of Hardy's fiction should find such terms adequately explicated. One need not be thoroughly conversant with the language of modern critical perspectives; all the book requires is that one should have read the ten stories on which the various contributors tend to focus — and then re-read them with greater appreciation and enjoyment.

Related Material

- Table of Contents for Schaefer and Brownson's Thomas Hardy's Short Stories: New Perspectives (2017)

- Bibliography for "Criticism of Hardy's Short Stories, 1982-2017"

- Thomas Hardy: A Biographical Sketch

- Illustrations for Hardy's Short Fiction

- Thomas Hardy and Magazine Fiction, 1870-1900

- A Short Bibliographical Survey of Thomas Hardy Studies

- Thomas Hardy's Novella The Romantic Adventures of a Milkmaid

- Thomas Hardy's "The Three Strangers" (1883): An Introduction

- She chanced to pause on the bridge near his house to rest herself (May 1893)

Created 4 September 2017