LOSELY related to the gentler forms of the sublime is Ruskin's conception of the "noble picturesque," which he presents in the fourth volume of Modern Painters. Several times in the course of his writings he attempts to explain the nature of what he felt to be a uniquely [220/221] modern aesthetic category characteristic of a uniquely modern style and subject matter in painting. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture he remarks upon the fact that signs of age appear pleasing to men, and that since the Renaissance, schools of art have arisen which concentrate upon such signs of age, thereby impressing upon "those schools the character usually and loosely expressed by the term 'Picturesque.'" Proposing to examine the nature of this art, he first points out that "probably no word in the language, (exclusive of theological expressions,) has been the subject of so frequent or so prolonged dispute; yet none remain more vague in their acceptance" (8.235). Here he may be referring to the Knight-Price controversy or, more likely, to the various definitions and usages of the term "picturesque" he had encountered in contemporary art periodicals and in the conversation of practitioners of the picturesque, such as his drawing masters J. D. Harding and Copley Fielding. Just how much Ruskin knew about the three main theorists of the picturesque, William Gilpin, Richard Payne Knight, and Uvedale Price, remains unclear. Although his frequent discussions of this term never mention any of these writers, typescripts of his notebooks in the Bodleian mention "Sir Uvedale Price on Picturesque"(Bodleian Library, Oxford, Eng. misc. c. 218.), but it is unclear whether he had read this or merely planned to. Ruskin, who had read Knight's work on mythology, may also have known his essays on the picturesque, though there is no indication of this, and of Gilpin there exists no evidence that he knew his writings. Far more important to Ruskin were his conversations and lessons with Fielding, Harding, and Prout, three painters, according to him, who were among the ablest and most important practitioners of this mode of art.

LOSELY related to the gentler forms of the sublime is Ruskin's conception of the "noble picturesque," which he presents in the fourth volume of Modern Painters. Several times in the course of his writings he attempts to explain the nature of what he felt to be a uniquely [220/221] modern aesthetic category characteristic of a uniquely modern style and subject matter in painting. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture he remarks upon the fact that signs of age appear pleasing to men, and that since the Renaissance, schools of art have arisen which concentrate upon such signs of age, thereby impressing upon "those schools the character usually and loosely expressed by the term 'Picturesque.'" Proposing to examine the nature of this art, he first points out that "probably no word in the language, (exclusive of theological expressions,) has been the subject of so frequent or so prolonged dispute; yet none remain more vague in their acceptance" (8.235). Here he may be referring to the Knight-Price controversy or, more likely, to the various definitions and usages of the term "picturesque" he had encountered in contemporary art periodicals and in the conversation of practitioners of the picturesque, such as his drawing masters J. D. Harding and Copley Fielding. Just how much Ruskin knew about the three main theorists of the picturesque, William Gilpin, Richard Payne Knight, and Uvedale Price, remains unclear. Although his frequent discussions of this term never mention any of these writers, typescripts of his notebooks in the Bodleian mention "Sir Uvedale Price on Picturesque"(Bodleian Library, Oxford, Eng. misc. c. 218.), but it is unclear whether he had read this or merely planned to. Ruskin, who had read Knight's work on mythology, may also have known his essays on the picturesque, though there is no indication of this, and of Gilpin there exists no evidence that he knew his writings. Far more important to Ruskin were his conversations and lessons with Fielding, Harding, and Prout, three painters, according to him, who were among the ablest and most important practitioners of this mode of art.

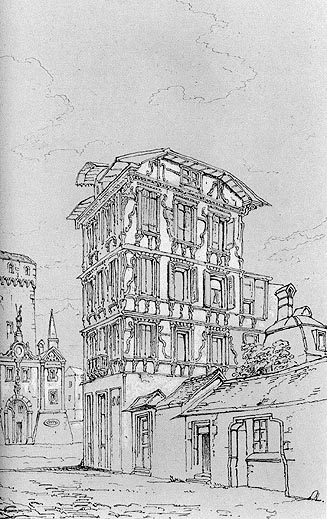

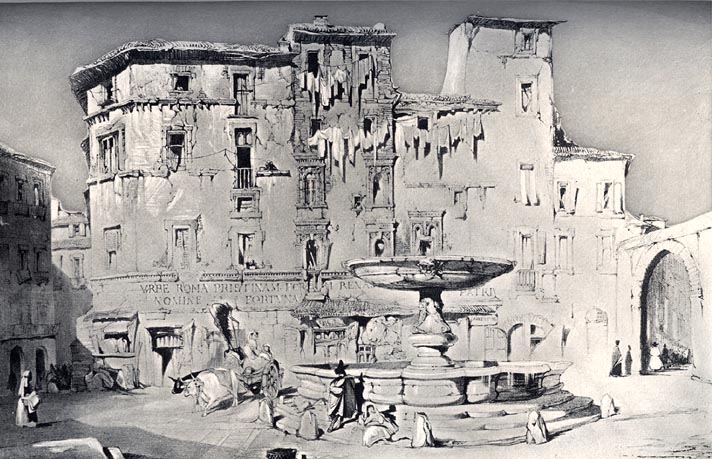

Two examples of the urban picturesque in Ruskin's drawings, the first made made when he was

in his sixteenth year, the second when he had developed a richer style. Left: Ancient Maison,

Lucerne, 1835. This drawing, which is reproduced facing Works, 2.434, is in emulation of the

inventor of this kind of urban picturesque, Samuel Prout, who was one of Ruskin's drawing

teachers. Right: Piazza Santa Maria del Pianto, Rome. [Not in print edition; click on picture for larger image.]

In The Seven Lamps of Architecture Ruskin described that "peculiar character . . . which separates the picturesque from the characters of subject belonging to the higher walks of art" as "Parasitical Sublimity" — "a sublimity dependent on the accidents, or on the least essential characters, of the objects to which it belongs" (8.236). According to him, the characters of line, shade, and expression which produce sublimity and hence picturesqueness include "angular and broken lines"(8.237) and bold contrasts of colors and light and shadow. Furthermore, these visual characteristics become even more effective "when, by resemblance or association, they remind us of objects on which a true and essential sublimity exists, as of rocks or mountains, or stormy clouds or waves" (8.237). Ruskin's discussion of the picturesque in the fourth volume of Modern Painters , which refers to these earlier remarks, further explains that the "essence of picturesque character" lies in "sublimity not inherent in the nature of the thing, but caused by something external to it; as the ruggedness of a cottage roof possesses something of a mountain aspect, not belonging to the cottage as such" (6.10). Ruskin had in fact used the same example previously in The Stones of Venice:

When a highland cottage roof is covered with fragments of shale instead of slates, it becomes picturesque, because the irregularity and rude fractures of the rocks, and their grey and gloomy colour, give to it something of the savageness, and much of the general aspect, of the slope of a mountain side. But as a mere cottage roof, it cannot be sublime, and whatever sublimity it derives from the wildness or sternness which the mountains have given it in its covering, is, so far forth, parasitical. (11.159)

His example of the rugged cottage roof reveals that the picturesque is a reduced form of the sublime which possesses its sharp oppositions and asymmetry without the large scale necessary to create impressions of grandeur. Since the irregular variety, which Ruskin takes to be the chief distinguishing mark of the picturesque, lacks any dominant unity, it does not partake of the beautiful; since it lacks vastness, it cannot produce the powerful emotions of the sublime. Depending in part on "resemblance or association"(8.237) of things sublime, the picturesque produces a minor form of delight.

As Ruskin explains in the fourth volume of Modern Painters, the "merely outward delightfulness [of picturesque subjects] — that which makes them pleasant in painting, or, in the literal sense, picturesque — is their actual variety of colour and form"(6.1s), and this pleasing variety necessitates a particular choice of style and subject:

A broken stone has necessarily more various forms in it than a whole one; a bent roof has more various curves in it than a straight one; every excrescence or cleft involves some additional complexity of light and shade, and every stain of moss on eaves or wall adds to the delightfulness of colour. Hence in a completely picturesque object, as an old cottage or mill, there are introduced, by various circumstances not essential to it, but, on the whole, generally somewhat detrimental to it as cottage or mill, such elements of sublimity — complex light and shade, varied colour, undulatory form, and so on — as can generally be found only in noble natural objects, woods, rocks, or mountains. This sublimity, belonging in a parasitical manner to the building, renders it, in the usual sense of the word, "picturesque." (6.15)

From this passage and others in which he describes the nature of the picturesque, one can conclude that Ruskin believes it is created by an irregular variety which characterizes a painting's line, lighting, color, and composition. This irregular variety, or "ruggedness" as he most frequently terms it, leads the artist in search of the picturesque to depict objects, such as ruins or rustic cottages, which provide rough, pleasing texture. Having chosen such subjects, the artist will then avoid the open, clear light which Ruskin advocated in his remarks on the beauty of infinity and will, instead, [224/225] employ strong shadows in the manner of "Rembrandt, Salvator, or Caravaggio" (8.237). Like these artists, the man in search of the picturesque uses shadow not primarily to depict an object, but as a subject in itself. In other words, the picturesque, a distinctively minor mode of art, uses the creations of man and nature to display technique, rather than employing the artist's skill for further ends. The delight created by a skillful treatment of line and shadow surmounts any potential delight in the objects depicted.

In thus citing ruggedness as the chief distinguishing characteristic of the picturesque, Ruskin agrees with Gilpin, who in the last decade of the eighteenth century had stated: "Roughness forms the most essential point of difference between the beautiful and the picturesque; as it seems to be that particular quality which makes the objects chiefly pleasing in painting" (Three Essays, 6). Although Ruskin was probably unaware of Gilpin, he had encountered such a view in many places; for example, Harding, his drawing master, explained in his Principles and Practice of Art (1845) that

variety is not only an essential property of beauty, but also of the picturesque, — a term which I use as significative of that quality of objects which renders them more peculiarly capable of being effectively and agreeably represented by Art.... The refined, chaste, and classical features of Greek architecture are beautiful simply: the wildness of nature is picturesque simply. The Greek ruin is both beautiful and picturesque, because it has mixed up with its refined beauty the irregularity and variety of the picturesque. (London, 1845, 79)

Ruskin, who frequently characterizes Harding's work as picturesque, agrees with his emphasis upon irregularity and variety. On the other hand, he does not accept his teacher's notion that "the wildness of nature is picturesque simply," and he several times mildly censures him for sacrificing the beauties of nature to the lesser asymmetries and irregularities of picturesque art. In the first volume of Modern Painters, for instance, even as Ruskin presents his friend's work as an example of excellence, he adds that "Harding's choice is always of tree forms comparatively imperfect, leaning this way and that, and unequal in the lateral arrangements of foliage. Such forms are often graceful, always picturesque, but rarely grand; and, when systematically adopted, untrue" (3.60l). Whatever his reservations, Ruskin had learned this conception of nature and the stylistic mannerisms necessary to achieve it in art from Harding's drawing lessons and published works, and from the sketching tours they took together.

Ruskin, however, first learned to appreciate the picturesque, not from Harding or Copley Fielding, his other drawing teacher, but from the works of Samuel Prout. In the catalogue he wrote for the exhibition of the artist's works at the Fine Art Society (1879-1880), he described how one of Prout's drawings which "hung in the corner of our little dining parlour at Herne Hill as early as I can remember . . . had a most fateful and continual power over my childish mind. . . . In the first place, it taught me generally to like ruggedness; and in the conditions of joint in moulding, and fitting of stones in walls which were most weatherworn, and like the grey dikes of a Cumberland hillside" (14.385). This love of picturesque ruggedness appears clearly in Ruskin's own drawings, many of which [226/227] surpass his model. The first volume of Modern Painters explains that "the reed pen outline and peculiar touch of Prout, which are frequently considered as mere manner, are in fact the only means of expressing the crumbling character of stone which the artist loves and desires" (3.194; see Plates 17-18), and Ruskin's own pencil drawings of architectural subjects emulate the older artist's style to create similar effects. And like Prout's drawings, many of his own attempt to portray "the knots and rents of the timbers, the irregular lying of the shingles on the roofs, the vigorous light and shadow, [and] the fractures and weather-stains of the old stones" (11.160). For example, Ruskin's drawings done when he was sixteen years old clearly emulate Prout's studies (illus. facing 1.8), and as he began to lay in washes and depict shadow more completely his works increasingly resemble the older artist's more finished drawings (illus. facing 14.426). Ruskin, on the other hand, never tried to rival Prout's placement of figures, one of the painter's skills he most admired, and, furthermore, since many of his own architectural subjects are delightfully incomplete sketches, they rarely rival the painter's larger works. Although his landscape drawings show the clear influence of his teachers and Turner, the pictures of architecture remain indebted to Prout.

He attributed important advances in the picturesque mode to this artist. In "Samuel Prout" (1849), an anonymous essay in the Art Journal, Ruskin pointed out that this artist had extended the picturesque to include urban scenes:

There is not a landscape of recent times in which the treatment of the architectural features has not been affected, however unconsciously, by principles which were first developed by Prout. Of those principles the most original were his familiarisation of the sentiment, while he elevated the subject, of the picturesque. That character had been sought, before his time, either in solitude or in rusticity; it was supposed to belong only to the savageness of the desert or the simplicity of the hamlet; it lurked beneath the brows of rocks and the eaves of cottages; to seek it in a city would have been deemed an extravagance, to raise it to the height of a cathedral, an heresy. (12.313)

Part of Prout's accomplishment in creating picturesque depictions of noble buildings lay in his ability to present the effects of age and human life upon his subjects. Until Prout, says Ruskin, excessive and clumsy artificiality characterized the picturesque: what ruins early artists drew "looked as if broken down on purpose; what weeds they put on seemed put on for ornament" (3.216). To Prout, therefore, goes credit for the creation of the essential characteristics lacking in earlier art, in particular "that feeling which results from the influence, among the noble lines of architecture, of the rent and the rust, the fissure, the lichen, and the weed, and from the writings upon the pages of ancient walls of the confused hieroglyphics of human history" (3.2l7). Prout, in other words, does not unfeelingly depict signs of age and decay chiefly for the sake of interesting textures, but rather employs these textures and other characteristics of the picturesque to create deeply felt impressions of age nobly endured.

In addition, Prout advanced this mode of art beyond concentration on the "minor elements of the picturesque, — craggy chasms, broken waterfalls, or rustic cottages" (13.368). Ruskin once wrote that if Turner "had only wanted what vulgar artists think picturesque," any English valley would have provided him with an endless supply "of old tree trunks, of young tree-branches, of lilied pools in the brook, and of grouped cattle in the meadows" (13.437). Neither Turner nor Prout were vulgar artists, and while Turner concentrated upon the infinite beauties of nature, Prout, more interested by the cityscape, redeployed aspects of picturesque technique to show the effects of men and time upon noble works of architecture.In the first volume of Modern Painters Ruskin insists that the pleasure we receive from the signs of age that Prout includes in his work distinguishes our delight in his art from "mere love of the picturesque" (3.2l7), and this distinction between "age mark"(3.207) and the conventional picturesque becomes, in the fourth volume, the Ruskinian opposition of the surface and Turnerian (or noble) picturesque. An examination of the reasons which lay behind Ruskin's continuing suspicion of the conventional picturesque reveals much that characterizes his theories of art. In the first place, he believes that "the modern feeling of the picturesque, which, so far as it consists in a delight in ruin, is perhaps the most suspicious and questionable of all the characters distinctively belonging to our temper, and art" (6.9). This lesser mode of the picturesque not only neglects the higher forms of the beautiful to portray broken rocks and thatched roofs, it also, by its natural concentration on ruin, encourages the artist and spectator to delight in sad, painful things for the sake of interesting lines and colors to the neglect of the human significance of the scene depicted. Thus, "in a certain sense, the lower picturesque ideal is eminently a heartless one" (6.19), for artists unthinkingly and unfeelingly create images of broken-down windmills and weakened men because they have visual interest.

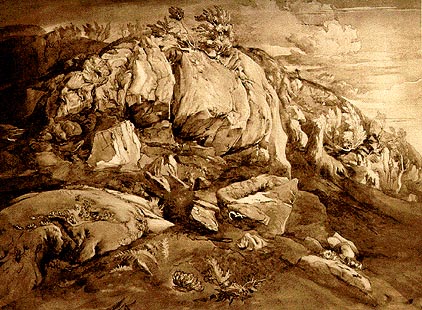

An example from Ruskin's own drawings of his idea that the artist must begin by being a seeing

and feeling creature, an agent of perception — rather than beginning with the assumption

that the artist is one who corrects a lesser nature that doesn't rise to one's standards: A

Study of Thistle at Crossmount, which is reproduced facing Works, 35.426. This watercolor,

which is representative of Ruskin's many brilliant landscape studies, raises naturalism to

visionary intensity as it reveals the beauties present in mundane, everyday reality.

[Not in print edition; click on the thumbnail for a larger image.]

In The Stones of Venice Ruskin wrote that the "whole function of the artist in the world is to be a seeing and feeling creature; to be an instrument of such tenderness and sensitiveness, that no shadow, no hue, no line, no instantaneous and evanescent expression of the visible things around him, nor any of the emotions which they are capable of conveying to the spirit which has been given him, shall either be left unrecorded, or fade from the book of record" (11.49). The lesser mode of the picturesque, however, necessarily reduces the artist to a seeing creature, forcing him to ignore the emotional — human — implications of his subject. This form of art, which requires an unhealthy dissociation of faculties in the artist, can only appeal to the aesthetic sensibilities of fragmented modern man. An example of the immoral abstraction implicit in the lower picturesque appears in Sir Charles Bell's Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression in the Fine Arts, which Ruskin several times quotes in his Modern Painters: "In Roman Catholic countries the church-door is open, and a heavy curtain excludes the light and heat; and there lie about those figures in rags, singularly picturesque" (6th ed., London, 1872, p. 16). Uvedale Price relates an anecdote which can serve as a parable here: One day when Reynolds and Wilson, the two painters, were looking at a scene, Wilson tried to point out a particular detail to his companion. "'There,' said he 'near those houses�therel where the figures are.' — though a painter, said Sir Joshua, I was puzzled. I thought he meant statues, and was looking upon the tops of the houses; for I did not at first conceive that the men and women we plainly saw walking about, were by him only thought of as figures in a landscape" (An Essay on the Picturesque, 379n). For Ruskin, [230/231] taking delight in figures in rags corrupted the artist and audience alike.

By the 1850s Ruskin had become increasingly aware of the social and moral implications of the picturesque and several times comments upon them. For example, in his diary entry for 12 May 1854 he wrote of a scene in Amiens:

All exquisitely picturesque, and as miserable as picturesque. We delight in seeing the figures in the boats pushing them about the bits of blue water in Prout's drawings, but, as I looked to-day at the unhealthy face and melancholy, apathetic mien of the man in the boat, pushing his load of peats along the ditch, and of the people, men and women, who sat spinning gloomily in the picturesque cottages, I could not help feeling how many suffering persons must pay for my picturesque subject, and my happy walk. (Diaries, II, 493; Ruskin quotes this passage with slight changes in phrasing as a note to the chapter on the Turnerian picturesque (4.24n).

Ruskin's problem — and his greatness — was that he "could not help feeling." He could not avoid the human implications of the picturesque scene before him: to do so would have required that he become purely a seeing creature, that he use human beings for aesthetic pleasure, that he treat them purely as objects. The attitudes contained in this diary entry appeared in different form six years later in the last volume of Modern Painters. Answering a "zealous, useful, and able Scotch clergyman," who had described a "scene in the Highlands to show (he said) the goodness of God," Ruskin proposes to take another look at this picturesque scene:

It is a little valley of soft turf, enclosed in its narrow oval by jutting rocks and broad flakes of nodding fern. From one side of it to the other winds, serpentine, a clear brown stream, drooping into quicker ripple as it reaches the end of the oval field, and then, first islanding a purple and white rock with an amber pool, it dashes away into a narrow fall of foam under a thicket of mountain-ash and alder. The autumn sun, low but clear, shines on the scarlet ash-berries and on the golden birch-leaves, which, fallen here and there, when the breeze has not caught them, rest quiet in the crannies of the purple rock. Beside the rock, in the hollow under the thicket, the carcase of a ewe, drowned in the last flood, lies nearly bare to the bone, its white ribs protruding through the skin, raven-torn; and the rags of its wool still flickering from the branches that first stayed it as the stream swept it down. A little lower, the current plunges, roaring, into a circular chasm like a well, surrounded on three sides by a chimney-like hollowness of polished rock, down which the foam slips in detached snow-flakes. Round the edges of the pool beneath, the water circles slowly, like black oil; a little butterfly lies on its back, its wings glued to one of the eddies, its limbs feebly quivering; a fish rises, and it is gone. Lower down the stream, I can just see over a knoll, the green and damp turf roofs of four or five hovels, built at the edge of a morass, which is trodden by the cattle into a black Slough of Despond.... At the turn of the brook I see a man fishing, with a boy and a dog — a picturesque and pretty group enough certainly, if they had not been there all day starving. I know them, and I know the dog's ribs also, which are nearly as bare as the dead ewe's; and the [232/33] child's wasted shoulders, cutting his old tartan jacket through, so sharp are they. (7.268-269)

Ruskin's bitterly ironic presentation of this Highland scene simultaneously exposes the implications of the picturesque and, as Rosenberg has pointed out, reveals "the insufficiency of the Wordsworthian view of nature" (23). The passage possesses a unique interest for a student of Ruskin's notions of the sister arts, for it shows him utilizing his own great skills at literary pictorialism rather differently than he had in earlier volumes of Modern Painters. Ruskin's usual practice, particularly in his first volume, is to create a word painting which he then frequently uses as a standard for judging a pictorial representation of a scene. In the opening volume of Modern Painters, he creates a powerful image of nature's colors near the Italian town of La Riccia to show how far from this splendor the older painters of landscape remain (3.277-279). The final volume of Modern Painters, in contrast, uses such literary pictorialism, not to show that nature is more beautiful than art, but to present the ugliness that a sentimentally artistic vision of nature conceals.

Ruskin knew that in order to paint a scene with words he had first to establish a center of perception, a narrative eye, next present recognizable elements of pictorial composition, and then move his narrative eye, camera-like, through the elements of the scene he creates for us. He therefore begins by placing the reader in the midst of the landscape, which exists in the narrative present: "It is a little valley." Next, he sketches in the oval shape of the valley, mentioning afterward the rocks and fern to convey its dominant texture and color. Lastly, he includes the standard pictorial motif of the winding stream, which serves to compose the picture, and then mentions the sunlight, thus focusing the reader's attention on what the light reveals. Thus far we have a verbal presentation, similar to many of those in the first volume, of beautiful landscape, embellished by details of color. But, having established the broad outlines of this Highland valley, the narrative eye moves closer and the increasing clarity of vision destroys the first impression of quiet loveliness. We move from the golden birch leaves to the carcase of a dead ewe, a necessary component, it seems, of life in nature, and we are drawn closer, perceiving the horrible details — the protruding white ribs, the raven-torn skin, and the rags of wool moving in the breeze. After pausing for this scene, the narrative eye moves on once again in a strikingly cinematic technique: we are moved further down the stream until we catch sight of a little butterfly, at which point we are moved closer, perceiving "its wings glued to one of the eddies, its limbs feebly quivering." A fish rises and the butterfly vanishes, an emblem of the way nature's beauties do not always survive natural predators. A third time we move on, catching sight of picturesque cottages and, at the bend of the stream, a "picturesque and pretty group." Lastly, the passage brings us nearer to this picturesque assemblage, forcing us to recognize the poverty and misery implicit in the picturesque. Ruskin's objections to the art in this mode was that it presented an incomplete, fragmentary and fragmenting, vision of nature. Taking neither art nor man seriously enough, it results in an incomplete, immoral delight in things intrinsically painful. His examination of this scene therefore demands that he guide the reader's [234/235] perceptions to an understanding that one cannot divorce the visual from the emotional, the aesthetically pleasurable from the other needs of man. [Follow for a similar point in Fors.]

Although Ruskin always remains highly critical of the lesser picturesque and is quick to point out its implications, he never condemns it entirely, because he believes that it arises in an essentially healthy human need for beauty. Thus, the fourth volume of Modern Painters explains that although "the hunter of the picturesque" (6.21) might appear a heartless monster to those of another place and time, in fact he is generally "kind-hearted, innocent of evil, but not broad in thought; somewhat selfish, and incapable of acute sympathy with others; gifted at the same time with strong artistic instincts and capacities for the enjoyment of varied form, and light, and shade, in pursuit of which enjoyment his life is passed, as the lives of other men are for the most part, in the pursuit of what they also like, — be it honour, or money, or indolent pleasure" (6.21). Even that "delight which he seems to take in misery is not altogether unvirtuous" (6.2l), since it contains the seeds of sympathy that could develop into better things. Moreover, this love of the picturesque also indicates a vague desire for the pastoral simplicities, a vague dissatisfaction with present life. As Ruskin previously explained in The Stones of Venice, such dissatisfaction is the natural condition of modern man in the modern cityscape: surrounded by the grey monotonies of the urban scene, man longs for something, anything, to delight his spirit. Therefore: "All the pleasure which the people of the nineteenth century take in art, is in pictures, sculpture, minor objects of virtu, or in mediaeval architecture, which we enjoy under the term picturesque: no pleasure is taken anywhere in modern buildings, and we find all men of true feeling delighting to escape out of modern cities into natural scenery" (10.207). Shortly after completing The Stones of Venice, Ruskin returned in his notebooks to the conditions of modern life which have produced the love of picturesqueness:

The real reason of it is this — that for more than a couple of centuries we have been studiously surrounding ourselves with every form of vapidness and monotony in architecture. It has been our aim to make all our houses and churches, alike; we have squared our windows — smoothed our walls; straightened our roofs — put away nearly all ornament[,] inequality, evidence of effort, and ambiguity, and all variety of colour. It has been our aim to make every house look as if it had been built yesterday; and to make all the parts of it symmetrical[,] similar and colourless.... All this is done directly in opposition to the laws of nature and truth. (Bodleian Library, Oxford, Eng. misc. c. 218)

The result has been, as he earlier pointed out, that the "picturesque school of art rose up to address those capacities of enjoyment for which . . . there was employment no more.... And thus the English school of landscape, culminating in Turner, is in reality nothing [236/237] else than a healthy effort to fill the void which the destruction of Gothic architecture has left" (11.225-226). Ruskin offers several solutions to the problems created by the modern city. First of all, he wishes to extend the influence, the enriching effects, of the art of Turner and other painters of landscape; secondly, he encourages his audience to revive a healthy mode of architecture, one which would provide the necessary stimulus for the minds and spirits of men; lastly, he tries to change the economic system which has led to such monotonous environments.

One important way to extend the influence of great artists like Turner is to educate the audience to appreciate the higher, or noble, form of the picturesque. In contrast to the "surface-picturesque" (6.16), which dwells on texture at the expense of emotion, the noble picturesque is produced by "an expression of sorrow and old age, attributes which are both sublime" (6.10). In other words, since the "higher condition of art . . . depends upon largeness of sympathy" (6.19), the noble picturesque, the form practiced by Turner, arises, not from neglect of the meaning of the scene depicted, but from concentration upon it. It is produced, then, by expression "of suffering, of poverty, or decay, nobly endured by unpretending strength of heart. Nor only unpretending, but unconscious. If there be a visible pensiveness in the building, as in a ruined abbey, it becomes, or claims to become, beautiful; but the picturesqueness is in the unconscious suffering" (6.14-l5). The noble picturesque, a form of the gentler sublime, is an associated, subjective aesthetic pleasure which demands the projection of human characteristics upon old buildings. Indeed, old buildings are to be considered as old, noble men. Much of this sad, pathetic sublimity is created by age. In the first volume Ruskin had written of the beauties of age itself, and these are apparently part of the sublime emotion which creates the noble picturesque: "There is set in the deeper places of the heart such affection for the signs of age that the eye is delighted even by injuries which are the work of time; not but that there is also real and absolute beauty in the forms and colours so obtained" (3.204). Even at this early period Ruskin distinguishes this pleasure from what he later called the surface-picturesque; for he remarks that although a building may have "agemark upon it which may best exalt and harmonize the sources of its beauty," our enjoyment of this sign of aging "is no pursuit of mere picturesqueness; it is true following out of the ideal character of the building" (3.207). This distinction between age-mark and mere picturesqueness became, in the fourth volume, the distinction between the noble and lower, or surface picturesque.

There are good reasons for taking Ruskin's definitions of the noble picturesque as the final and representative statement of his aesthetic position. The picturesque, in some sense, is a combination of the sublime and the beautiful and is midway between them, a reduced, gentler, less exalted form of both. And as an intermediary class it reminds us of Uvedale Price's idea that the picturesque should bridge the sublime and the beautiful. (According to Price, "Picturesqueness appears to hold a station between beauty and sublimity; and on that account, perhaps, is more frequently, and more happily blended with them both, than they are with each other." Price, An Essay on the Picturesque, 82.) In this last major statement of his aesthetic [238/239] position, Ruskin tried to formulate a description of that kind of pleasure which he thought most characteristic of the art of his contemporaries, and in so doing he shows his close relation to theorists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Like them, after he had been concerned with the most violent aspects of the sublime, and the most tranquil forms of beauty, he presented what was in effect a third aesthetic category which emphasized calm, more tranquil, yet subjective effects. Ruskin's statements about the picturesque are also characteristic, not only because he related it to an aspect of the contemporary sensibility which troubled him, but because he here most fully accepts an aesthetic which is patently subjectivist and associationist. This change reflects the changes that were going on, or were being prepared for, in Ruskin's thought as he turned increasingly toward the problems of modern man in modern society. The new humanism which fully appears in the last volume of Modern Painters is presaged by the picturesque which gains its effect not, as with beauty, from a figuring forth of divine qualities, but from human associations. Ruskin's description of the picturesque, which at so many points contradicts his ideas of beauty, shows how difficult it had been for him to maintain that his beauty of order contained the pleasures most suited to the art of his time. Ruskin had at first denied the sublime the dignity of a separate aesthetic category, but after formulating his theories of beauty, he found it necessary to use sublimity to contain a wide spectrum of aesthetic effects. The picturesque, which is a subcategory of the sublime, is the final expression of this inability to maintain a classicistic theory of beauty.

Last modified 6 May 2019