Her Animal Paintings

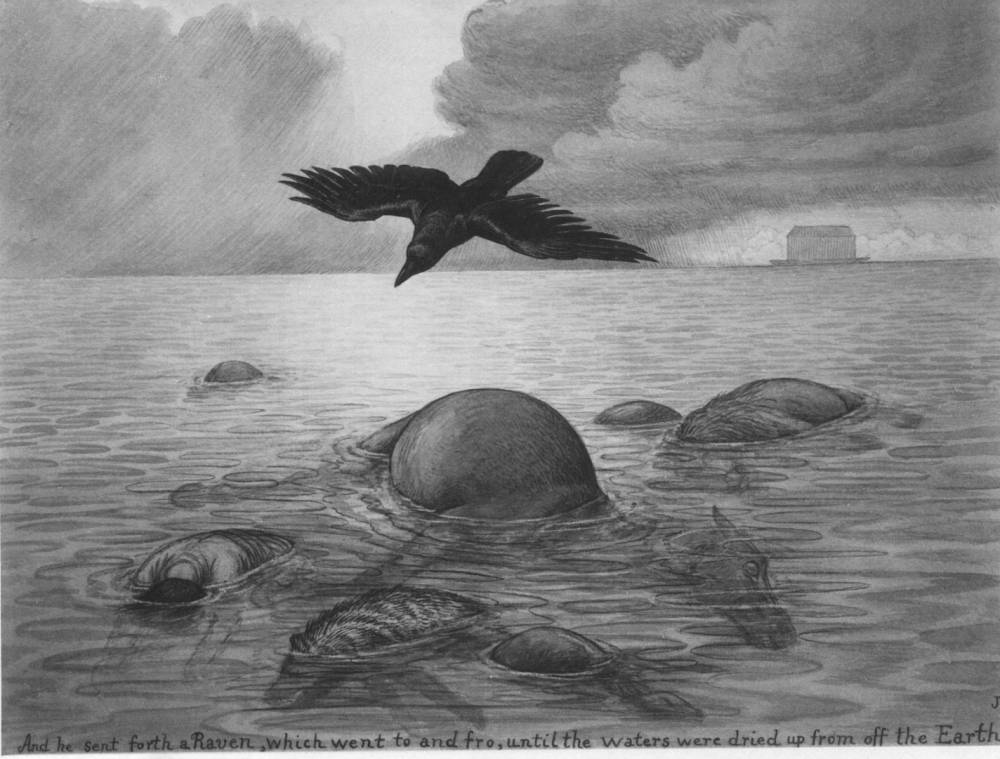

Left: The Raven. Right: The Ram Caught in the Thicket . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

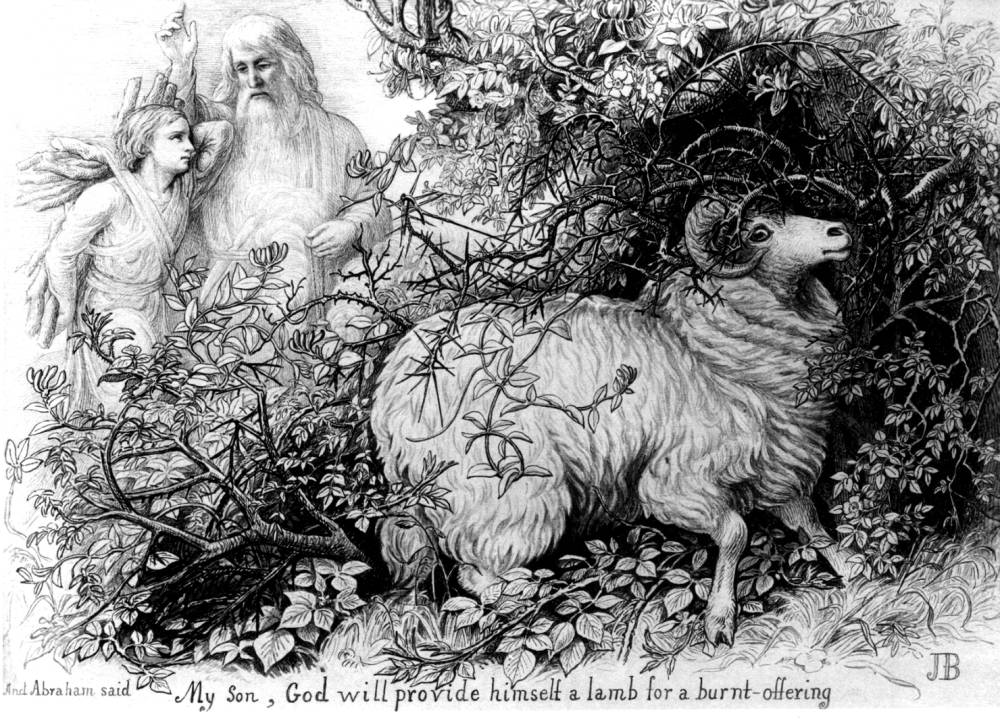

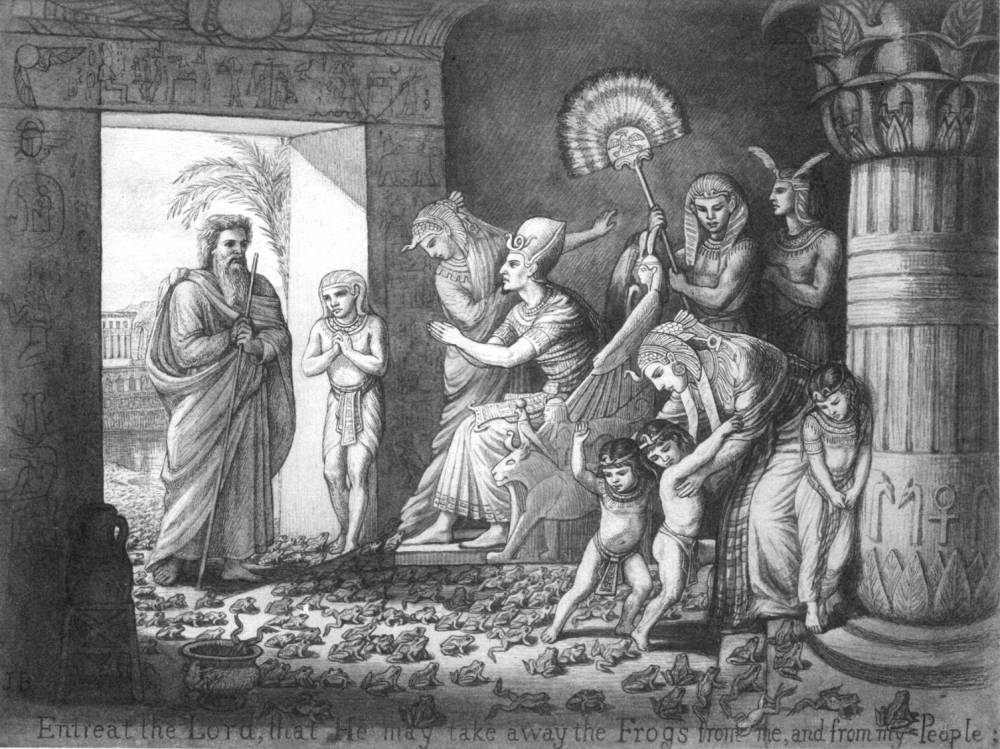

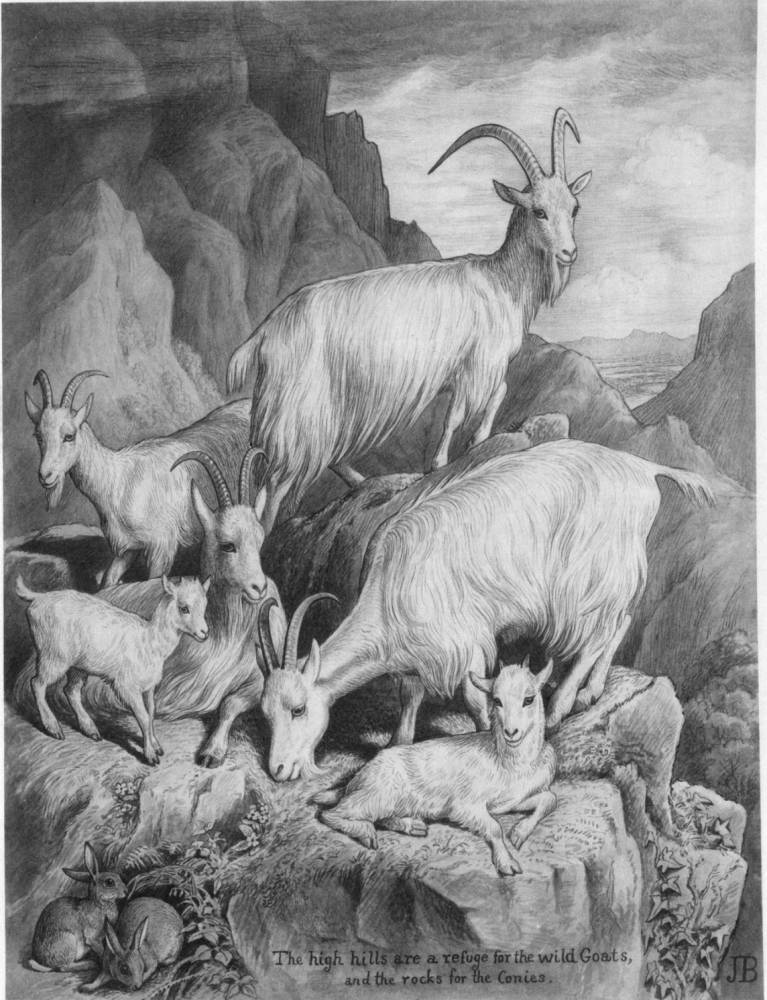

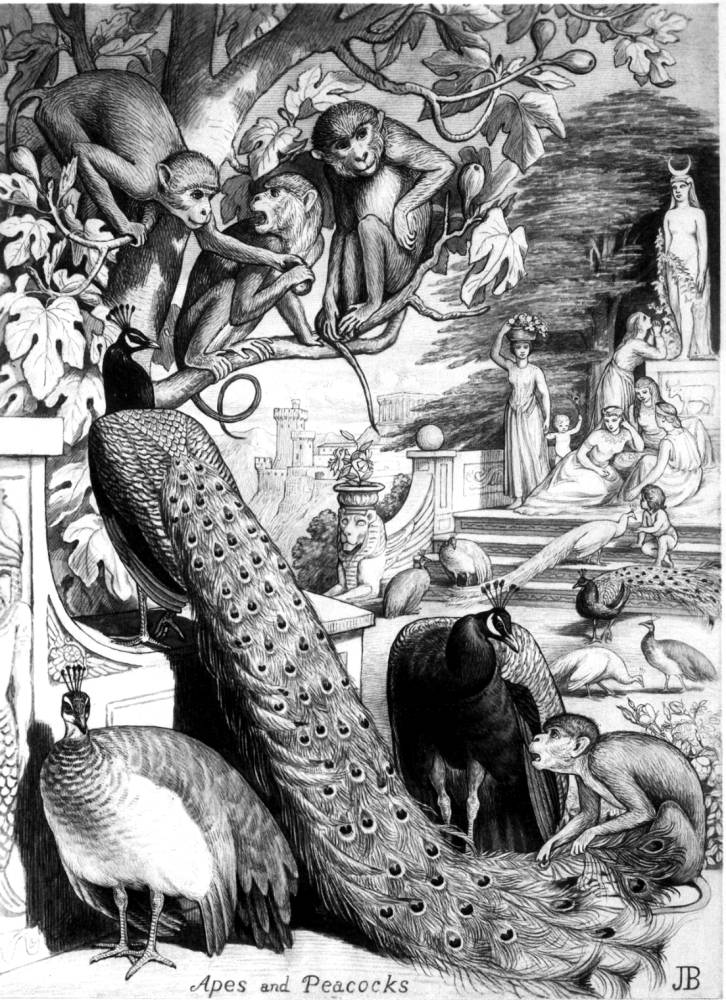

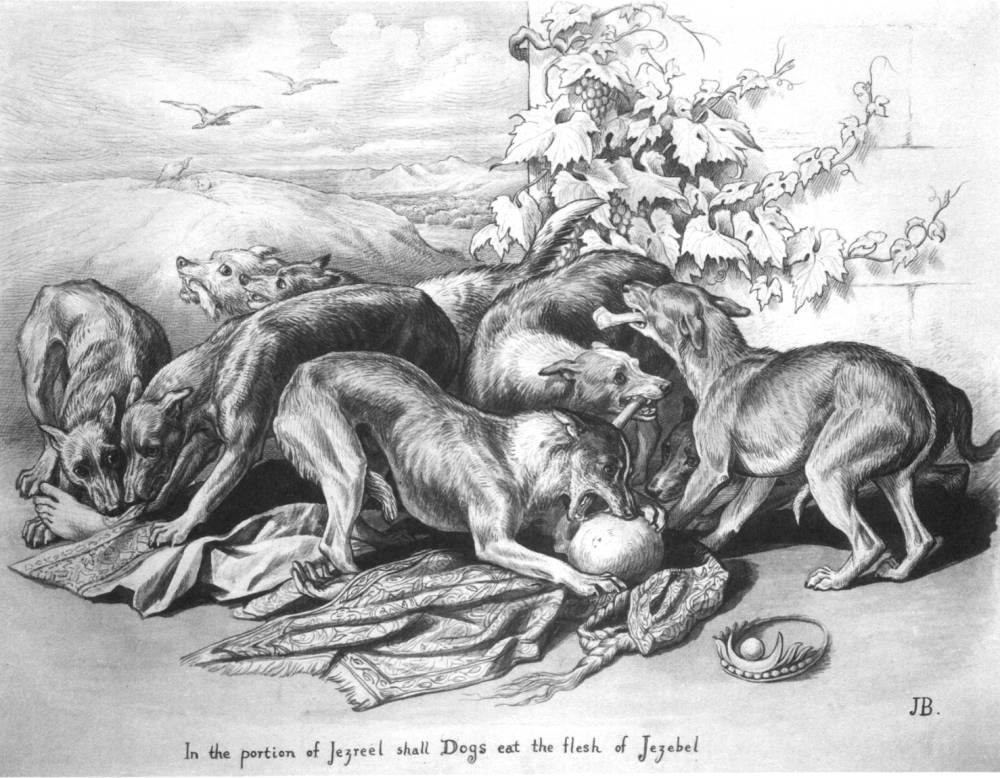

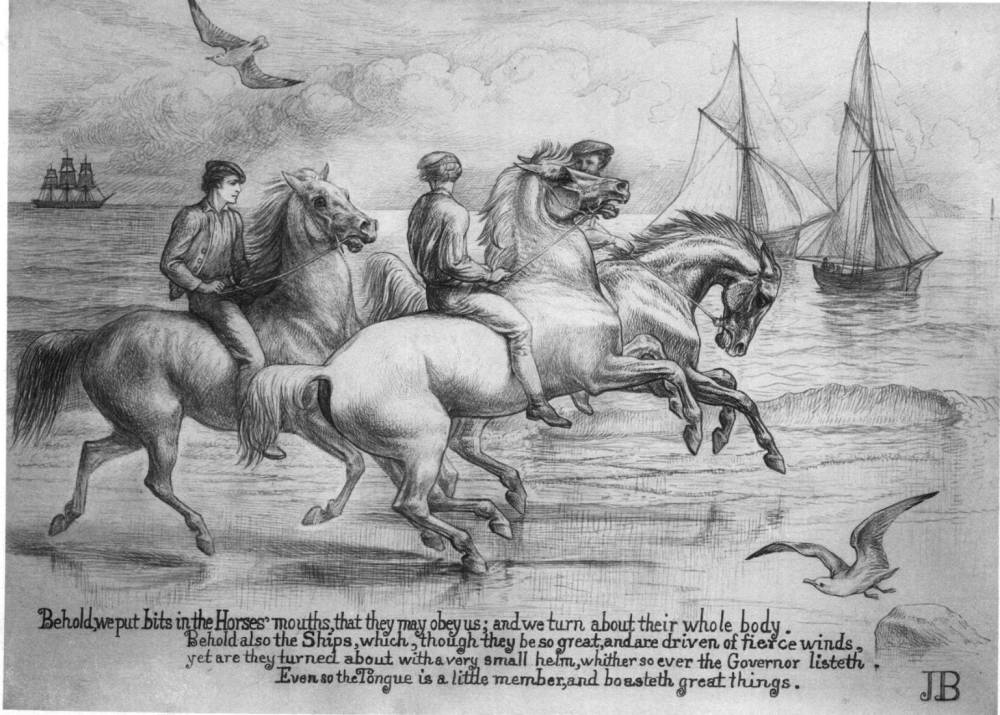

By the 1850s, Blackburn was gaining recognition as an artist and illustrator of bird and animal life. In 1853, she published Illustrations of Scripture by an Animal Painter (title-page), her first important book. Her 22 illustrations accompanying passages from the Old and New Testament feature a host of birds—a raven, a dove, hens and chickens, storks and swallows, and a peacock—as well as animals—including frogs, dogs, goats, lions, and lambs.

Left: The Plague of Frogs. Middle: Goats and Conies. Right: Apes and Peacocks.

The book earned high praise from Edwin Landseer, who told Blackburn’s publisher he admired her “‘extreme originality of conception and admirable accuracy of the knowledge of the creatures delineated. Having studied animals during my whole life, perhaps my testimony as to the truth of the artist’s treatment of the Scripture Illustrations may have some influence’” (qtd. Fairley 42). She received congratulatory letters from Thackeray—who writes, “‘What a deal of pleasure you have given me!’” (qtd. Fairley 42)—and Ruskin, who notes, “‘I have your book and am much pleased with it. It is impressive and in many respects delightfully original’” (qtd.Fairley 43).

Left: Jezebel. Right: Behold, we put bits in the Horses’s niuths. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

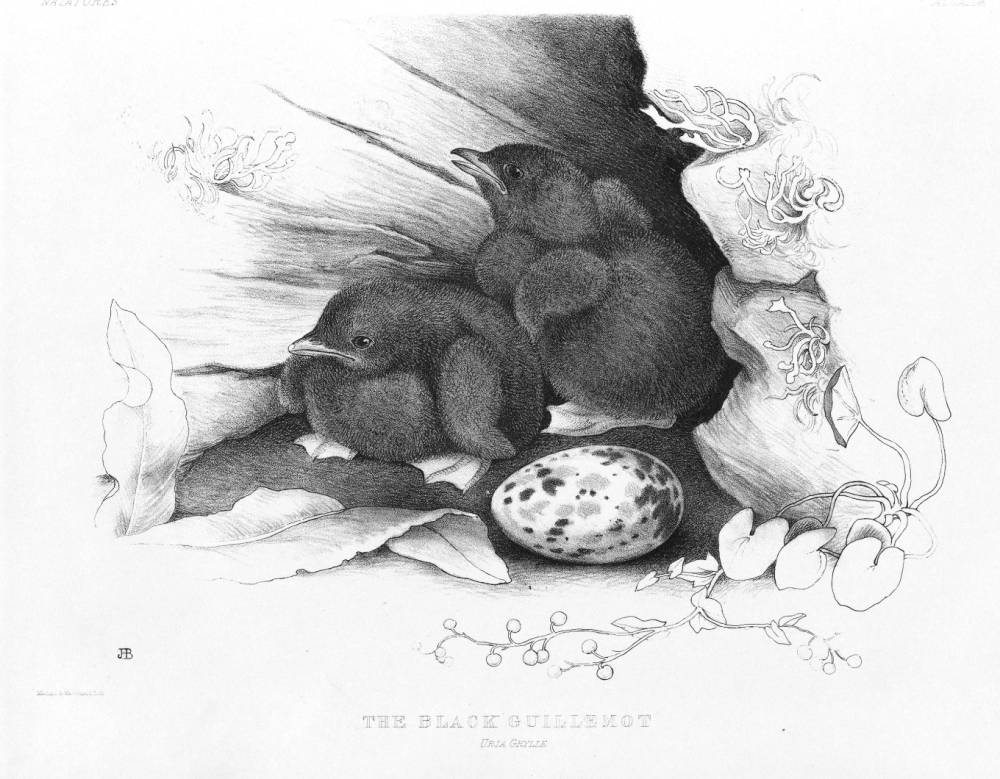

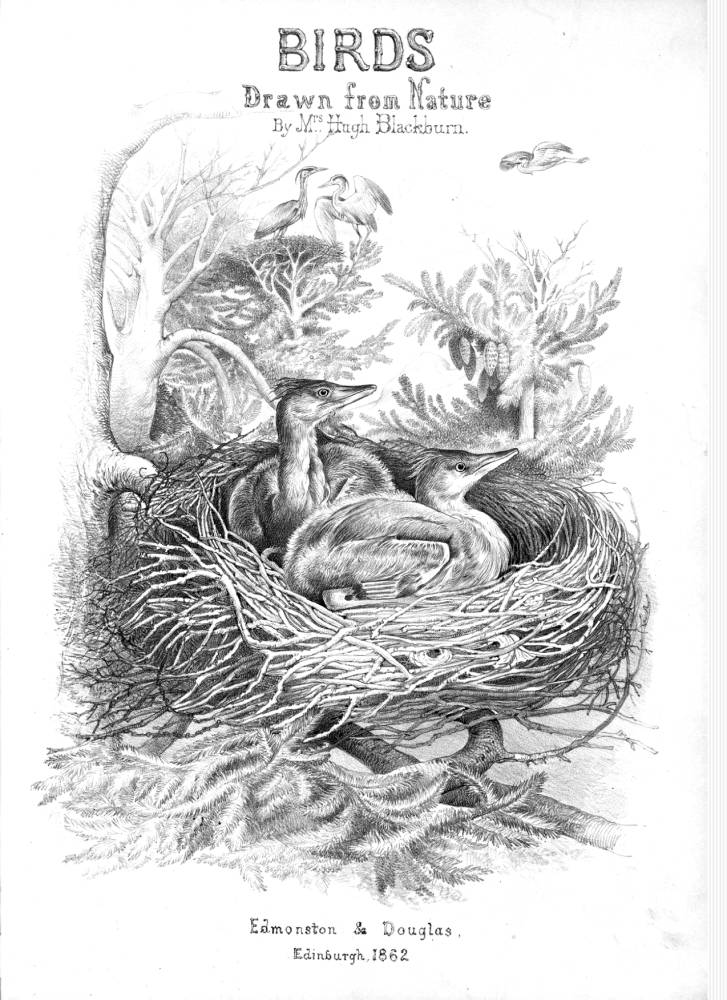

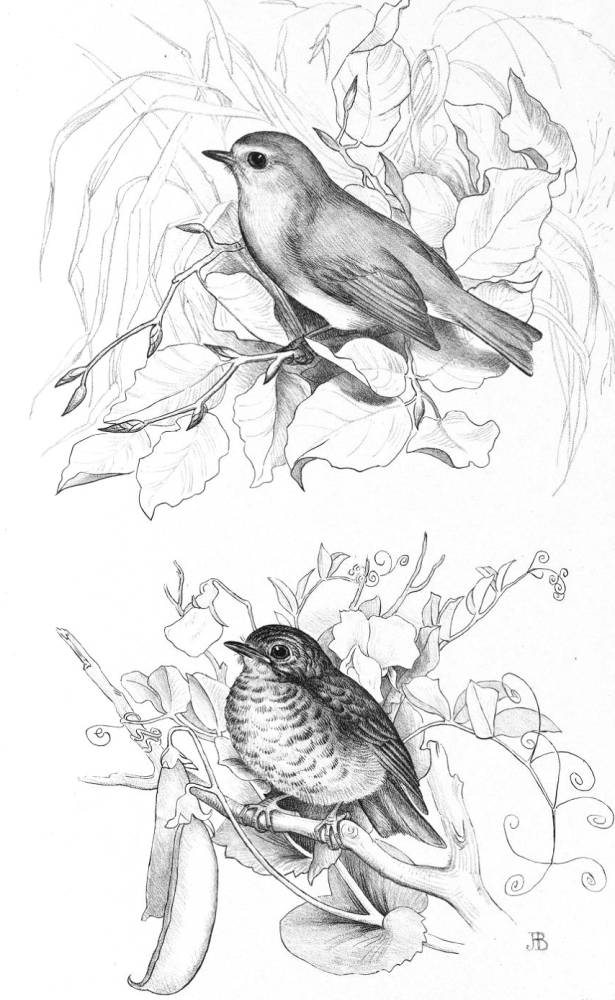

In 1861, Illustrations of Scripture was serialized in the family magazine Good Words, which increased her popularity; for a decade she continued to publish her illustrations in Good Words, which, unlike its two secular rivals in the field of illustrated Victorian periodicals, The Cornhill and Once a Week, promised wholesome Christian entertainment. Illustrations of Scripture (republished in 1866 under the title Bible Beasts and Birds), Birds Drawn from Nature (1862, 1868), and Birds from Moidart and Elsewhere (1895) form her trio of ornithological publications that led a reviewer in the Westminster Budget (January 19, 1896) to conclude: “There are naturalists and naturalists. It is a pity that there are not more like Mrs. Blackburn” (qtd Fairley 87). Birds from Moidart—the name of the southwest corner of Inverness-shire and the location of her summer home in Roshven—was her last ornithological work due to her failing eyesight. At the urging of her husband and friends, Blackburn wrote her Memoirs in 1899-1900 with the editorial help of her husband.

Drawing from Life: Her Orthinological Work

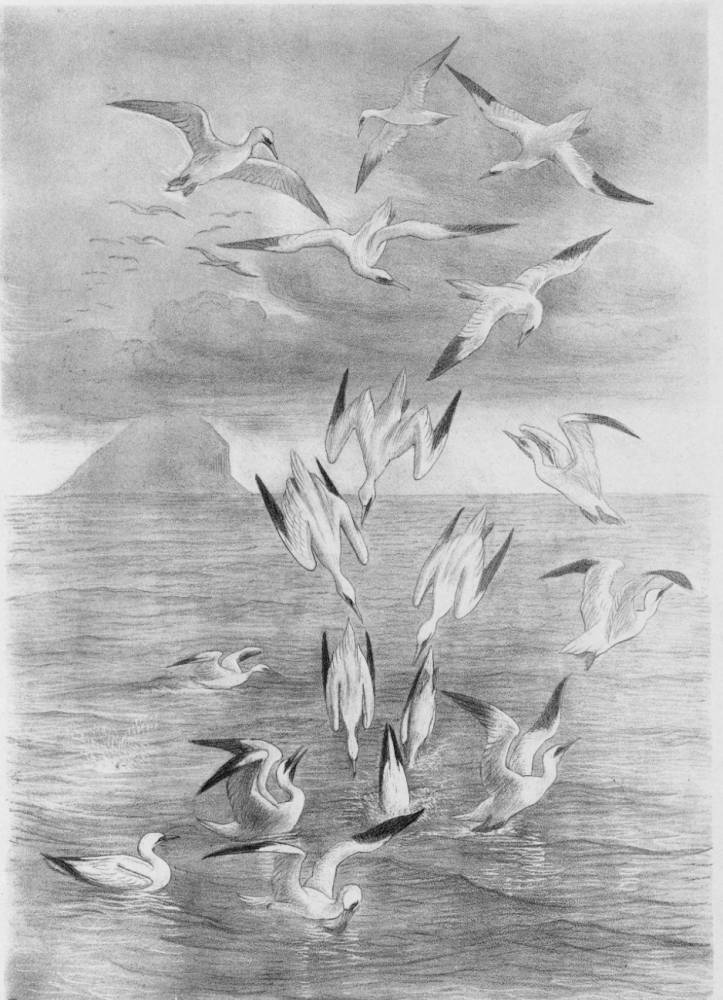

Blackburn’s artistry might best be described as a mix of scientific accuracy guided by the Pre-Raphaelite tenet of “truth to nature.” She strove to present truthfully the appearance and habits of birds and animals based on her many years of observing nature. While Audubon drew from dead specimens and James Gould from stuffed models, Blackburn made it her lifelong practice to sketch “from nature” as she called it, hence the punning title of Birds Drawn from Nature (my emphasis).

In the preface to the book (accessible in print and online archives), Blackburn describes her method at some length:

THE DRAWINGS, of which a few are here engraved, have been made either from the living bird, or from specimens so fresh as to preserve most of the characteristic appearances of life, while the attitude and background have been studied from careful observation of the habitats of the wild birds. This has of course involved a good deal of trouble, and it is not likely that a single observer will have the opportunity, under these restrictions, of obtaining good drawings of the whole series of British Birds. Such considerations have no doubt induced most illustrators of the subject (even Bewick himself) to put up with a stuffed skin for a lay figure, and, apparently, to label drawings so made as “from nature.”

But in the present instance the artist, without neglecting to refer to stuffed “specimens,” has refused to be guided by them, in the belief that drawings really from nature (and such only) may be made to give a representation of nature[.]

To Blackburn, sketching a bird “from nature” required careful observation of a living bird’s behavior in its natural habitat. She was known to wade through deep water, climb ladders, and scale high cliffs to obtain what she above calls “good drawings”; even poor weather was not off putting, notes Fairley, since “on one occasion while attempting to paint a swan the paint froze to her brush” (54). She sometimes brought birds into her home to complete a sketch. As a child she housed a live pigeon in her doll’s house, and a Common Raven was also a pet. At times, she captured birds and held them in temporary captivity; she caught a heron on the grounds of her husband’s family home and kept it in a bathroom at her rooms in Glasgow, feeding it sardines, until she finished her painting and released it back to its natural habitat.

Left: Solan Geese Fishing (near Ailsa Craig). Middle: The Tawny Owl (Syrnium Stidula). Right: Group of Herons. [Click on images to enlarge them and to read Blackburn’s comments.]

Blackburn also took pains to annotate her sketches in Birds Drawn from Nature, noting valuable details that augment the scientific accuracy of her work. These notations placed across from a depiction of a bird, indicate among other things where she observed the bird, its behaviors in the water, the time of year she took the sketch, winter or summer plumage, the composition of a nest, or the number of eggs a bird typically laid. The printing of her work also mattered to Blackburn. As she notes in the “Preface” to Birds Drawn from Nature, to ensure as “few interpreters as possible between nature and the actual print the drawings have been copied on to the stone (or zinc plate) by the same hand as made the original drawings, or in some instances the drawing has been made on the stone direct from nature.” The “same hand” is obviously Blackburn’s. Multi-talented, Blackburn sketched, etched, engraved, and printed her own plates, and these skills contribute to the freshness of her bird drawings that, to her contemporaries, rival those of Bewick.

The Redwing (Turdus Iliacus). as originally printed a one of the few hand-colored versions.

A reviewer of Birds Drawn from Nature notes in The Scotsman in 1862: “‘We have seen no such birds since Bewick’s. We say this not ignorant of the magnificent plates by Selby, Audubon, Wilson, and Gould’” (qtd. in Fairley 55). Thirty years later, Beatrix Potter, after meeting Blackburn at a cousin’s home, composed a lengthy diary entry on June 5th, 1891 entitled “Impressions of Mrs. Hugh Blackburn” in which she makes a similar claim; “Mrs. Blackburn’s birds do not on the average stand on their legs so well as Bewick’s, but he is her only possible rival” (208). But to Blackburn, her “only possible rival” did not always hold to her same exacting standards of drawing from nature.

In her annotation to “Solan Geese Fishing” in Birds Drawn from Nature, she calls out her rival for compromising his method: “Bewick’s cut of this bird is a great warning not to trust a stuffed ‘specimen,’” cautions Blackburn (21). But in her preface to Birds from Moidart, Blackburn singles out Bewick’s influence from childhood and articulates a hope to inspire others as Bewick has inspired her: “The first book I ever possessed was Bewick’s British Birds, given to me when I was four years old, and I should be very glad to think that this work of mine might give to others, even in a small degree, the pleasure that book gave me—that it might lead them to consider the fowls in the air as capable of affording delight in other ways besides filling a game bag, or adorning a hat” (“Preface”). Did Blackburn know that Potter, in turn, danced with joy while summering in Scotland upon receiving Blackburn’s Birds Drawn from Nature for her tenth birthday?

Left: Title-page of Birds Drawn from Nature. Middle: The Redbreast (Erythaca Rubecula). Right: The Hedge Sparrow (Accentor Modularis).

Last modified 10 January 2021