[Apart from the cover picture, the accompanying images come from sources other than the book under review. See individual captions. Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

Front jacket of the book under review, showing part of Franz Xaver Winterhalter's portrait of the Queen in 1843.

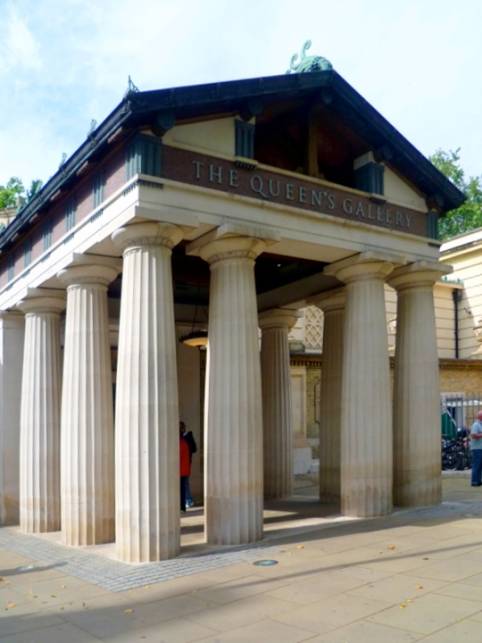

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert loved books: they had about 40,000 volumes at Windsor Castle alone. The Royal Collection's latest publication, timed to accompany an exhibition with the same title at the Queen's Gallery, would surely have delighted them. It seduces the eye from the start, with young Victoria looking beguiling on the cover, and a romantic endsheet design featuring national emblems. The frontispiece has matching colour portraits of the royal couple by the miniaturist Sir William Ross, and before the introduction come two full-page reproductions of larger, more romantic coloured-chalk portraits by Charles Brocky. What follows is an exceptionally well illustrated catalogue of the royal couple's many contributions to the collection, each image accompanied by a detailed commentary. The whole production provides valuable insights into the cultural life of the royal family and indeed of their age.

The book's title sets its parameters: the catalogue covers the years of the royal couple's marriage, with the exception of the last section, which deals with memorials to Prince Albert. As Jonathan Marsden's comprehensive introduction demonstrates, here were a husband and wife with "artistic genes" (14), their taste formed in early life by exposure to great art and ideas about art, and their commissions often driven by the wish to celebrate their life together with gifts of choice artworks. The nineteen sections cover a wide spectrum, from medieval masterpieces to the latest developments in photography; from large canvases and full-size statues to exquisite miniatures; from heavy pieces of furniture to delicate pieces of lacework; and from grand jewellery for state occasions to touchingly personal family mementos.

Left to right: (a) Drawing of the Queen, aged twenty, by Sir Edwin Landseer (Lee, 108). (b) The marriage of Victoria and Albert in the Chapel Royal of St James's Palace in 1840 (Morris and Murat, facing p.45). (c) "Her Majesty and the Infant Prince Arthur — From a Painting by Winterhalter" in The Illustrated London News, 28 August 1852, p.172. (d) "Cousins," showing Queen Victoria with her much-loved cousin the Duchess of Nemours, who died at Claremont in Surrey in 1857, from a painting by Winterhalter again, in Letters of Queen Victoria, II: following p.196.

"Portraits," devoted to the family itself, makes the perfect opening. Here we find a young and radiant queen, not the later, matronly figure in black, and much else to support the twenty-first century reassessment of her as vivacious and passionate. Among the many likenesses, the cover portrait itself (which Alison Plowden also used for the front cover of her 2007 biography, The Young Victoria), is the most attractive: "Here Queen Victoria is seen in an intimate and alluring pose, leaning against a red cushion with her hair half unravelled from its fashionable knot" (67). The portrait was a private, not an official one, having been commissioned from Franz Xaver Winterhalter as a gift for Prince Albert on his twenty-fourth birthday in 1843. Much more formal yet just as unusual in its own way is the full-length sculpture of the Queen in classical garb and with sandaled feet, holding a laurel crown in one hand and a scroll in the other. It was intended as a companion piece to the Prussian sculptor Emil Wolff's statue of a Albert.as a bare-legged Greek warrior, and was originally tinted — a typical work by the neo-classical John Gibson. The couple's accoutrements in these statues suggest their roles: "the Queen [holding the laws and a laurel crown] as the upholder of the law and bestower of honour, and the Prince [with sword and shield] as her defender" (70).

The laurel crown is just the right touch for this book. Throughout their marriage, Victoria and Albert continued to "bestow honours" in the form of commissions, in order to produce unique gifts for each other and also to adorn their various residences. They were also concerned simply to build up their collection. From Sir William Ross alone they commissioned more than 140 portraits of each other and the family, and from Winterhalter more than 120. As for sculpture, Marsden points out that by 1866 the number of busts in the Grand Corridor at Windsor alone had more than doubled (14). The next section, "Contemporary Painting and Sculpture," is by far the longest, confirming what Prince Charles describes in the Foreword as "the remarkable role that art played in their partnership of marriage." Particularly notable is their patronage of many European as well as British artists. This was natural enough in view of the close connections with other royal families, as shown in the useful genealogical table at the beginning. Winterhalter, for example, was German, introduced to the Queen through her uncle Leopold's second wife, Queen Louise of the Belgians (63), and similar ties accounted for several of the other important European artists favoured by the Queen, including two important sculptors, Barons Henri de Triqueti and Carlo Marochettii. Winterhalter, Triqueti and Marochetti had all been favourites of the Orléans court, which was exiled to England in 1848 with the collapse of the July Monarchy in France, and made its headquarters at Claremont in Surrey. Triqueti and Marochetti both spent most of the rest of their lives in England, while the royal family gave Winterhalter so much work to do that for many years from 1842 onwards he spent large parts of each summer or autumn in London. However, within their budgetary restrictions the royal couple made a point of spreading their patronage as widely as possible. Artists from who they acquired single works include such disparate figures as the apocalyptic northern painter John Martin (see The Deluge, one of the sequence to which the Royal Collection's item belongs), the illustrator George Cruikshank, and another of the Dickens circle, Augustus Egg.

Patronage was only one way of fostering the arts. After "Contemporary Painting and Sculpture" comes "Early Italian and Northern European Painting." This includes a marvellous medieval triptych of "The Crucifixion and Other Scenes" by Duccio di Buoninsegna, purchased through Prince Albert's artistic adviser, Ludwig Gruner — just the sort of thing that inspired the Pre-Raphaelites. An appreciation of such items would have spread beyond the royal collection into the wider artistic community, especially since Gruner became a neighbour and good friend of Charles Lock Eastlake and his wife Elizabeth Rigby, themselves highly influential figures in the art world of the time. Gruner brought in many of the royal couple's new acquisitions, more than sixty paintings and sculptures alone between 1845 and 1855 (19). This was the time when their estates were growing. "Architecture and Decoration," the next section, shows watercolours and photographs of the various royal residences, a further section being entirely devoted to Balmoral. and the Highlands. Particularly noteworthy is a watercolour by James Roberts showing the long "Marble Corridor" of the new Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. With its polychrome Minton tiles ("one of the earliest such uses of tiles in a domestic setting," 197), and space for new sculptures, it shows both the royal couple's trend-setting interior decoration and their firm intention to accommodate more artworks.

The next section, "Music, Theatre and Entertainment," confirms their interest in and support for other cultural areas besides the visual arts. One acquisition was an extravagantly ornamented, gilded grand piano for one of the drawing-rooms of Buckingham Palace, a showpiece among the many pianos they owned. Most items here, however, including Ernst Rietschel's bust of Mendelssohn, and the Queen's own characterful little operatic watercolours, have a more intimate feel. Queen Victoria was particularly fond of the composer, and "enchanted" also by Jenny Lind, "the Swedish Nightingale" (238), whom she sketched in one of her most celebrated roles, as Maria in Donizetti's La Fille du Régiment. She was full of praise too for Charles Kean's production of Macbeth, attending performances of it at the theatre, and having it staged at Windsor as well. She commemorated this very superior "home theatrical" with paintings commissioned from Louis Haghe, two of which were hung at Osborne.

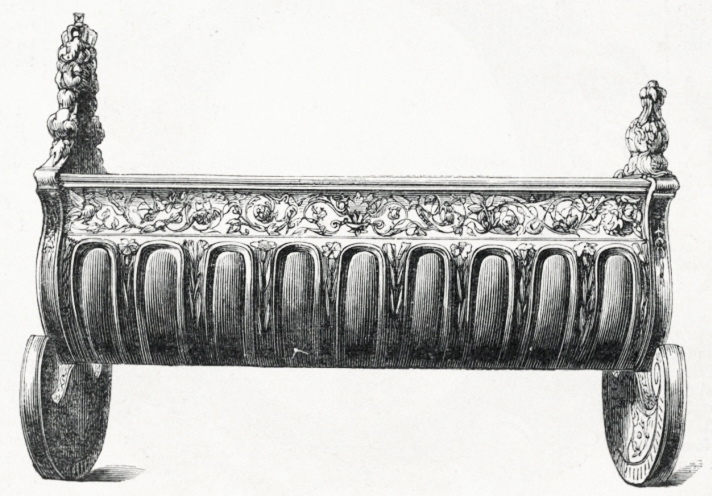

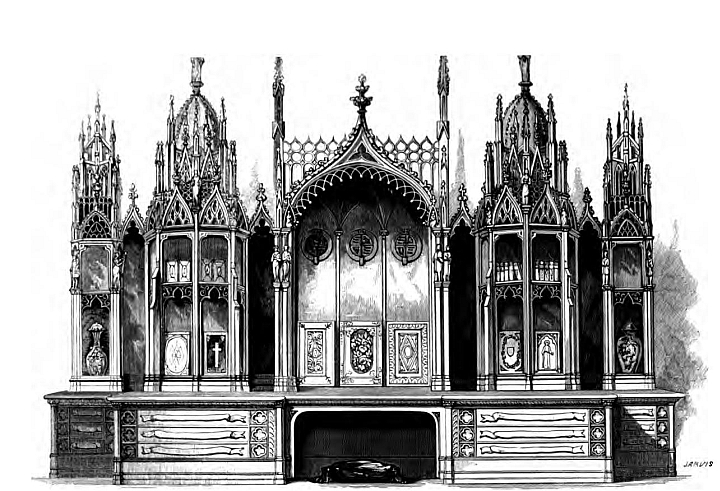

Three illustrations from the Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the Great Exhibition. Left to right: (a) A boxwood rocking cradle designed by William Harry Rogers and elaborately carved by his father William Gibbs Rogers for Princess Louise in 1850, described in the Art Journal as "altogether the best specimen of Mr Rogers's carving" (qtd. in Marsden 247). (b) An elaborate Gothic bookcase in oak, designed by Carl Leistler and prepared as a present to the Queen from the Emperor of Austria. (c) A Minton custard-cup set from the "Victoria dessert service" of 1850-51, described in the catalogue itself as one of "exceeding beauty" (114)

Subsequent sections feature furniture, such as the boxwood cradle commissioned by Queen Victoria for Princess Louise, and later shown at the Great Exhibition; metalwork, including a number of very fine mid-century pieces from the Elkington firm; ceramics, including several pieces each from the Sèvres and Minton firms; gorgeous state jewellery and insignia, and much simpler, sentimental pieces of personal jewellery, like a charm bracelet in which each little enamelled heart-shaped locket contains a lock of a royal infant's hair. This last was one of the Queen's greatest treasures. Then there are sections on "Textiles, Fans and Accessories," including some walking sticks with jewelled or carved heads, one of the latter clearly revealing Prince Albert's taste for the medieval. More up-to-date are the "Souvenir Albums and Topography" which follow — Queen Victoria's records of places visited and memorable sights seen, one of which is a view of St George's Hall, Liverpool, with which she was greatly impressed.

Left: Entrance to the Queen's Gallery, exhibition home of the Royal Collection since 1962 (formerly a conservatory of Buckingham Palace, then a chapel, and now considerably expanded). The entrance portico was only added in 2002, but there is a gallery named after Sir James Pennethorne, the architect responsible for some of the work in this part of the palace in the Victorian period.

Right: Prince Albert holding the catalogue of the Great Exhibition of 1851, by John Foley, in the Albert Memorial, London.

Influence from the Royal Collection would have filtered down not only through patronage and links with the art and design worlds, but more directly through public display. There was no Queen's Gallery then, and only a few items, such as the brilliant new insignia for the British orders of chivalry, would have been glimpsed on special occasions. But the Queen regularly lent paintings to the Royal Academy and the Royal Society of Arts exhibitions, and in the 1840s began opening Hampton Court and then Windsor Castle to ticket-holders. From 1855 the royal couple also agreed that a series of engravings from the collection should be published in what became known as the Art Journal. Most importantly, perhaps, they lent a number of items (helpfully listed in the first appendix) to Prince Albert's own project, the Great Exhibition. This is the subject of the next section. Orientalism received as big a boost as medievalism here, thanks partly to the Indian Galleries, which were filled with spectacular gifts from the Indian princes. The Times correspondent felt quite unable to do justice to the ivory throne and footstool from the Rajah of Trevencore: "To give, by description, any idea of the magnificence of this piece of Court furniture from the East is plainly impossible" ("The Great Exhibition"). The royal couple also acquired many new items for their collection at the exhibition,and these are also listed here. Perhaps the humblest was a "carved book-tray executed by a ploughman" (453).

Of the four remaining sections of the book, three deal with books, photography and "royal artists." Of these, the first confirms the high cultural tone of a family who set up libraries for their staff at both Windsor and Balmoral. The Queen also shared in the new interest in photography — indeed, she had a passion for it, and the photography section includes a fine hand-coloured daguerreotype of Prince Albert in 1848 by William Kilburn, and a very splendid albumen print of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1854, in formal dress, by Roger Fenton — the first to have been taken of the Queen "as reigning monarch, rather than wife and mother" (414), although it still shows her looking more like a bride than a Queen, gazing adoringly up at her spouse. It is a particular pleasure to see first-class reproductions of these early photographs, and to read about their histories. As for the "royal artists," these are Queen Victoria, Princess Albert and Princess Victoria, their eldest daughter (some of the artists they commissioned are dealt with briefly in the introduction). Most of the works discussed here are by Queen Victoria herself, a gifted amateur watercolorist who filled over fifty albums and sketchbooks with pictures of her children, favourite landscapes, stage scenes and so on. From the evidence of the one painting by the younger Victoria, The Entry of Bolingbroke (1857), the Princess Royal was even more talented. But what emerges above all, from both this and the preceding section , is the Queen's own lively enthusiasm for new sights, new experiences and new developments; her own creative instincts and abilities; and her keenness to record whatever interested her for posterity. Again, this makes a valuable corrective to later views of her, and indeed of the age. In case anyone still needs telling, both were characterised more by energy and enterprise than earnestness.

This book, of course, does justice to the sensibilities of Prince Albert as well as Queen Victoria, who gladly deferred to her husband's artistic judgment. It also.credits him for early presentation, arrangement and cataloguing initiatives. With his sudden death, the couple's wonderful "partnership of patronage" came to an abrupt end (50). The last section of this book is as splendid as the rest, showing the Royal Collection's versions of some of the memorials to the Prince. Yet it is sombre too. One of the items shown is the bronze cast of Marochetti's effigy of him in the Frogmore Mausoleum. He lies on an ermine mantle, his military uniform almost covered by his Garter robes, apparently asleep after having made his valuable contribution to the cultural life of his adopted nation. This book is a timely reminder: culture is not an optional extra, but the inspiration and hallmark of an age.

References

Marsden, Jonathan, ed. Victoria & Albert: Art & Love. London: Royal Collection Publications, 2010. 480pp. �45.00. ISBN 978-1-905686-21-6. Hardback. �45.00

"The Great Exhibition" (Review). The Times, 16 June 1851, p. 8. Available in the Times Digital Archive. Viewed 2 November 2010.

Picture Sources

[Note: The following can all be downloaded from the Internet Archive.]

The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue: The Industry of Nations. London: George Virtue, 1851.

Lee, Sidney. Queen Victoria: A Biography. New ed. London: John Murray, 1904.

Morris, Charles, and Halstead Murat. The Life and Reign of Queen Victoria, including Lives of King Edward VII and Queeen Alexandra. Chicago: International Publishers, 1901.

Queen Victoria. The Letters of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty's Correspondence between the Years 1844-1858, Vol. II. Ed. Arthur Christopher Benson and Viscount Esher. New York: Longman, Green, 1907.

Last modified 5 November 2010