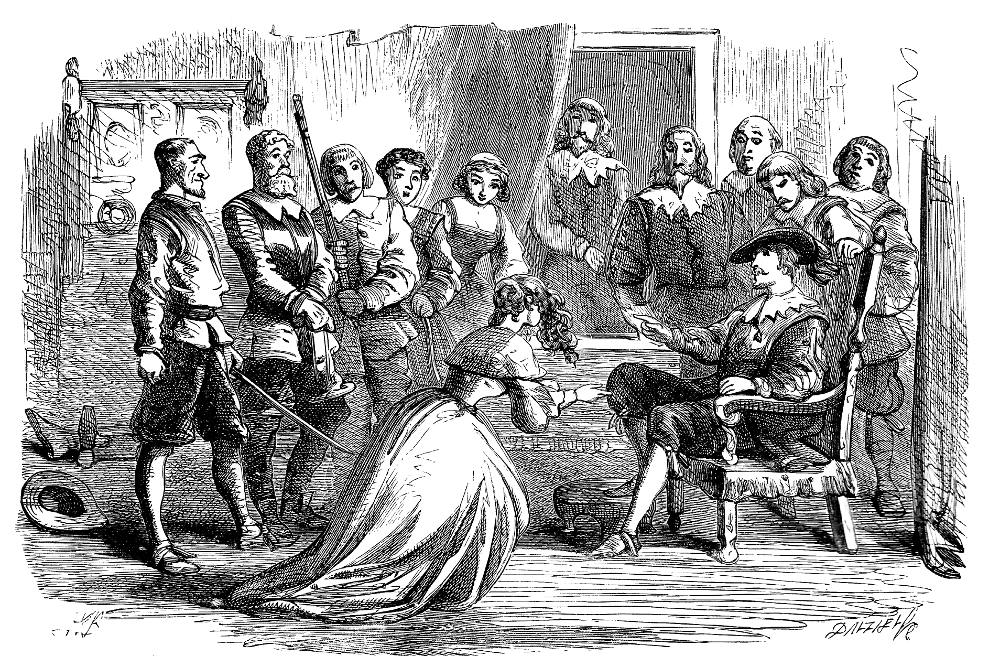

Charles II. at Ovingdean Grange by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), eighth serial illustration for William Harrison Ainsworth's Ovingdean Grange: A Tale of the South Downs, Part 9 (July 1860), Book VIII, "Charles the Second at Ovingdean Grange," Chapter XI, "In which the Tables are turned upon Stelfax," 10.2 cm high by 15.2 cm wide, wood-engraving, vignetted, facing p. 322. Source: Ainsworth's Works (1882), originally published in Bentley's Miscellany, and, upon its completion as a serial, in volume form by George Routledge and Sons, London (July 1860). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Associated with the Illustration: The King in Hiding Passes Judgment

But another matter now claimed the king’s attention. One of his enemies was gone to his account, but the more dangerous of the two was left, to expiate his offences with his life. Charles prepared to pass judgment upon him.

Disarmed, with his elbows tightly pinioned to his side by a sword-belt, having a guard on either hand ready to stab him or shoot him if he attempted resistance — which, indeed, in his present state, was wellnigh impossible — the Ironside captain, who refused to move at John Habergeon’s bidding, was forcibly dragged before the king.

Meanwhile, Charles having seated himself in a richly carved oak chair, high-backed, and provided with a cushion of Utrecht velvet, placed his foot on a stool covered with the same material, which was set before him with the most profound respect by old Martin Geere. At the same time the company stationed themselves on either side of the chair occupied by his Majesty, thus giving the group some slight resemblance to a gathering round the throne. On the right of the king, and close to the royal chair, stood Colonel Maunsel leaning on his drawn sword. On the same side were Lord Wilmot and Colonel Philips. On the left stood Clavering, with his rapier bared, and held with its point to the ground. Near to Clavering were Dulcia and Mr. Beard. At some little distance, near the inner room, was a group, consisting of Giles Moppett, Elias Crundy, and others of the household, together with Patty Whinchat and Temperance Stone. When Stelfax was brought before the king, John Habergeon would fain have compelled him to make an obeisance, but the stubborn Republican refused, and, drawing himself up, said, “I will not bow the head to the son of the tyrant.”

“Let him be,” said Charles. “It is too late to teach him manners. What hast thou to say, fellow,” he continued, addressing the prisoner, “why I should not order thee to instant execution?”

“Nothing,” replied Stelfax, resolutely. “I am prepared to die. A soldier of the Lord would scorn to ask life from the son of Rehoboam.” [Book VIII, "Charles the Second at Ovingdean Grange," Chapter XI,"In Which The Tables Are Turned Upon Stelfax," 322-323]

Commentary: History meets Historical Fiction

In focussing on Dulcia's interceding on behalf of Stelfax with the King, Phiz has minimized the importance of the military prisoner (left) in the scene, and has done little to distinguish the other figures in the composition — and all he shows us of the slain Micklegift is a pair of feet and ankles (left). The old cavalier, Colonel Maunsel, and John Habergeon, although secondary characters, are of importance in the dialogue, and cannot tell by form or juxtaposition which figures they are, let alone the King's attendants Wilmot and Phillips. Clearly, the man guarding the prisoner is Clavering: "with rapier bared, and held with its point to the ground" (321). The dramatic scene should be effective as the culminating moment in Dulcia's relationship with Stelfax, but it lacks the tension of its textual equivalent.

After 1860: A Marked Falling Off in Phiz's Work

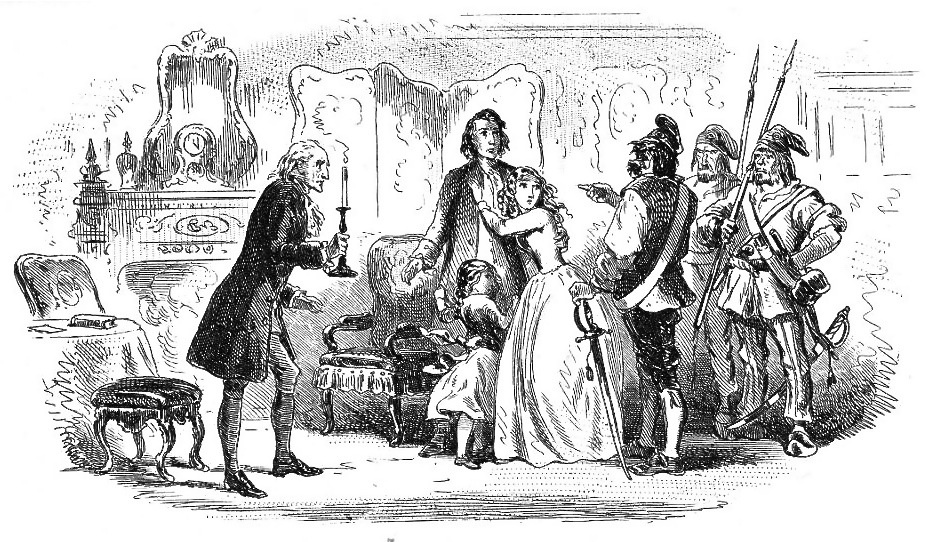

Above: Phiz's gripping steel-engraving of the second arrest of Darnay, denounced by Dr. Manette himself: The Knock at the Door (November 1859).

A trio of scruffy patriots arrest Charles Darnay as an Enemy of the Republic in Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Here Phiz particularizes even the minor characters by their dress, postures, and juxtapositions, so that, although the viewer readily identifies Lucy and Charles Darnay, the viewer has little difficulty in distinguishing which is the arresting officer. However, Dickens had provided a scene with fewer characters and a better focus on the principals: the doctor (left, with candle), the husband, wife, and child (centre). The other late judgment scene, Before the Tribunal lacks the inner tension most clearly evident in the earlier courtroom scene, The Likeness (July 1859).

Thus, the present illustration, completed just a year later, seems to represent a falling off in Phiz's powers of composition and execution as even the background here contributes little to the crucial scene which determines the fates of the Ironside colonel and the royalist damsel. The work is well below the high standard of engraving and composition that Phiz achieved in the dark plates for Mervyn Clitheroe in 1858 and of the regular steel-engravings for A Tale of Two Cities the following year. David Croal Thomson in his assessment of Phiz regards the year 1860 as pivotal in the quality of the illustrator's creations. Although in such watercolours as Una and the Red Cross Knight (an 1860 study for Sir Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene) Phiz continues to reveal something approaching his old skill at delineating scenes from literature, Thomson sees a marked falling off at about this time:

The year 1860 has been chosen for the division of the miscellaneous books illustrated by "Phiz" because chiefly up to that time he had produced which in the vast majority of cases was worthy of admiration; but after 1860 his illustrations became more mannered in style and execution. They gradually declined in merit until 1867, when the severe illness mentioned frequently overtook him, and from that time nothing absolutely original came from his pencil. The prime of he artist was between 1840 and 1860, and from 1860 to 1880 was, broadly speaking, the period of his decline. This does not mean that everything Hablot Knight Browne did before 1860 was excellent nor everything since that time was bad. [16-217]

Working methods

- Phiz's Illustrations for William Harrison Ainsworth's Ovingdean Grange (1859-60)

- "Phiz" — artist, wood-engraver, etcher, and printer

- Etching, Wood-engraving, or Lithography in Phiz's Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities?

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Ovingdean Grange: A Tale of the South Downs. (1860). Illustrated by Phiz. Ainsworth's Works. London & New York: George Routledge, 1876.

Buchanan-Brown, John. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Thomson, David Croal. Life and Labour of Hablôt Knight Browne “Phiz.” With One Hundred and Thirty Illustrations. London: Chapman and Hall, 1884.

Vann, J. Don. "William Harrison Ainsworth's Ovingdean Grange: A Tale of the South Downs in Bentley's Miscellany, November 1859 — July 1860." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. 30-31.

Created 28 October 2019

Last modified 9 February 2021