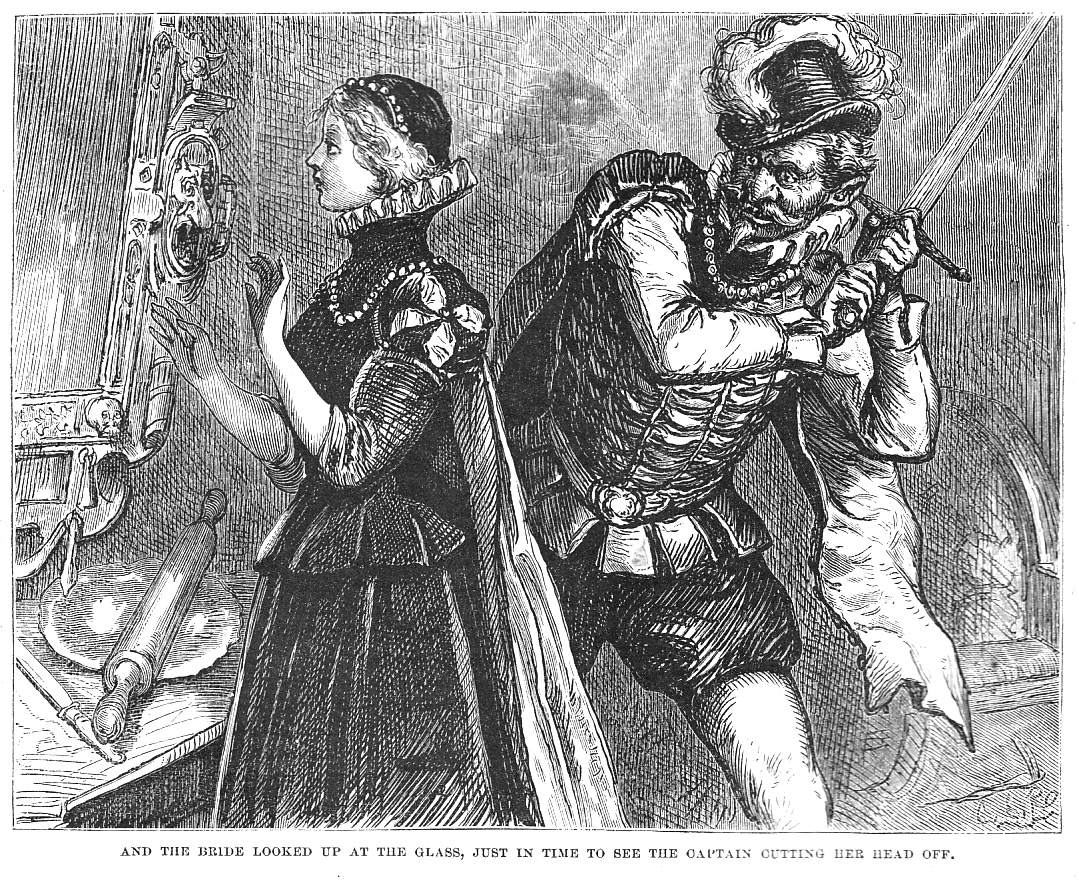

"And the bride looked up at the glass, just in time to see the Captain cutting her head off" — wood engraving from "Nurse's Stories," chapter 15 in The Uncommercial Traveller by Charles S. Reinhart (1844-1896). 10.3 cm high by 13.3 cm wide (half-page, horizontally mounted, 67). The wood-engraving illustrates a scene on the facing page (66). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated

Captain Murderer's mission was matrimony, and the gratification of a cannibal appetite with tender brides. On his marriage morning, he always caused both sides of the way to church to be planted with curious flowers; and when his bride said, "Dear Captain Murderer, I never saw flowers like these before: what are they called?" he answered, "They are called Garnish for house-lamb," and laughed at his ferocious practical joke in a horrid manner, disquieting the minds of the noble bridal company, with a very sharp show of teeth, then displayed for the first time. He made love in a coach and six, and married in a coach and twelve, and all his horses were milk-white horses with one red spot on the back which he caused to be hidden by the harness. For, the spot would come there, though every horse was milk-white when Captain Murderer bought him. And the spot was young bride's blood. (To this terrific point I am indebted for my first personal experience of a shudder and cold beads on the forehead.) When Captain Murderer had made an end of feasting and revelry, and had dismissed the noble guests, and was alone with his wife on the day month after their marriage, it was his whimsical custom to produce a golden rolling-pin and a silver pie-board. Now, there was this special feature in the Captain's courtships, that he always asked if the young lady could make pie-crust; and if she couldn't by nature or education, she was taught. Well. When the bride saw Captain Murderer produce the golden rolling-pin and silver pie-board, she remembered this, and turned up her laced-silk sleeves to make a pie. The Captain brought out a silver pie-dish of immense capacity, and the Captain brought out flour and butter and eggs and all things needful, except the inside of the pie; of materials for the staple of the pie itself, the Captain brought out none. Then said the lovely bride, "Dear Captain Murderer, what pie is this to be?" He replied, "A meat pie." Then said the lovely bride, "Dear Captain Murderer, I see no meat." The Captain humorously retorted, "Look in the glass." She looked in the glass, but still she saw no meat, and then the Captain roared with laughter, and suddenly frowning and drawing his sword, bade her roll out the crust. So she rolled out the crust, dropping large tears upon it all the time because he was so cross, and when she had lined the dish with crust and had cut the crust all ready to fit the top, the Captain called out, "I see the meat in the glass!" And the bride looked up at the glass, just in time to see the Captain cutting her head off; and he chopped her in pieces, and peppered her, and salted her, and put her in the pie, and sent it to the baker's, and eat [sic] it all, and picked the bones. [66]

Commentary

The grisly tale of the self-congratulatory Captain Murderer (a sort of domestic Richard the Third) is one of a series of gruesome "Nurse's Stories," first published in All the Year Round on 8 September 1860. Whereas British Household Edition Edward Dalziel chose to realize a moment in the Faustian story of Chips the shipwright from the workaday world of a nineteenth-century shipyard, the American Household Edition illustrator has selected far more sensational material for realization.

Although loosely based on Perrault's Eastern tale of "Blue Beard" (1697), a favourite of a number of Victorian writers, including the Brontës and Thomas Hardy, the story told by the Uncommercial Traveller's nurse in childhood at "Dullborough" (that is, Rochester-Chatham) seems far more contemporary and markedly European (despite the lack of law enforcement), with its allusions to carriages and church services; however, Reinhart's using the costumes and properties of the Elizabethan period is certainly plausible, and may be intended to make a connection between the grotesque oral tale of serial murders and the sometimes violent world of Shakespearean tragedy. Offered a number of alternatives for illustration, Reinhart chose the most gruesome story with the most sensational plot: the villain's chopping up and consuming a succession of young brides. The wood-engraving's Elizabethan mode of dress distances the story's action, and seems to exonerate Victorian Britain as the site of such flagrant domestic abuse. Whereas Dalziel delights in the marine shed setting, emphasizing ropes, chains,rigging, and tackle, Reinhart use six only three significant properties: the ornately framed mirror, the golden rolling pin, and pie pastry on a silver board. The Poe-esque detailing of the mirror's frame reveals the illustrator's intention to embed subtle signals as to the fate of the young woman gazing vacantly into the mirror: the scroll signifies the unfolding of the plot; the skull suggests her imminent death; and the hideous, wide-mouthed gargoyle (with a shape reminiscent of a door-knocker) implies the impending horrors of decapitation and cannibalism which the mirror is about to witness, and the reader to see in the mind's eye. To these ominous signs the young woman seems utterly oblivious as, vain of face, she focuses on the centre of the mirror as opposed to its informative frame. Already, however, she has begun to raise her hands (sleeves rolled up to work on the pastry) in apprehension, perhaps detecting the upraised sword reflected in the mirror.

Relishing the moment preceding the young woman's death and the demonic expression of her psychopathic husband of just one month, Reinhart has brilliantly synthesized the story's chief elements and made the moment preceding the young wife's death — despite the gross improbabilities of the multiple murders going undetected and unpunished — insistently real. Already the latest victim has failed to understand that she herself will serve as the ghastly filling for the unspeakable pie, a property that Dickens has borrowed from Shakespeare's most horrific drama, Titus Andronicus. Frowning from both inward rage and concentration, Captain Murderer raises his blade as he focuses on the wife's neck, conveniently isolated from the head by her furbelow. Reinhart thus challenges the reader to complete the fatal blow in the mind's eye, and anticipate the chopping up, cooking, and ghoulish consumption. Since the picture is located opposite the text it realizes, as he or she proceeds down the facing page the reader/viewer moves back and forth between letterpress and engraving, noting not merely the elements realized but also those that the imaginative illustrator has added. Most significant is the Shakespearean context, an era of violent action and elegant costumes. The husband and wife are dynamically matched as binary opposites, the young wife's stillness, innocence, naivete, and blond beauty contrasting the kinetic energy of the hideously faced swordsman in the opulent dress of an Elizabethan gentleman, a civilised veneer that disguises the murderer's true nature, revealed in his manic gaze.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller, Hard Times, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Il. Charles Stanley Reinhart and Luke Fildes. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Il. Edward Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Hartnoll, Phyllis, ed. The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1972.

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition." New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Slater, Michael, and John Drew, eds. Dickens' Journalism: 'The Uncommercial Traveller' and Other Papers 1859-70. The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens' Journalism, vol. 4. London: J. M. Dent, 2000.

Created 2 March 2013

Last modified 6 January 2020