"I remember what a change seemed to have come over my dear father's face when we saw him again," Mamie recalled, "... how pale and sad it looked." All that night he sat beside the death-bed, keeping watch over the little girl's corpse with Mark Lemon. The next morning he wrote a tender and careful note to Catherine, clearly anxious that this latest news might augment her own suffering and even lead to some kind of breakdown. "I think her very ill," he told her, although he knew his daughter to be dead. Forster went down to Malvern with the letter and, when the news was eventually broken to her, Catherine fell into a state of "morbid" grief and suffering. [Ackroyd 627-28]

Dora Annie Dickens (16 August 1850 — 14 April 1851)

Charles and Catherine Dickens's ninth child and third daughter was Dora Annie Dickens (1850-1851), who lived just eight months. The child, a little sister for Mary (Mamie) and Katey Dickens, and their six brothers, was born at Devonshire Terrace, Marylebone Road, almost opposite York Gate, Regent's Park, the London home of the Dickenses from November 1839 through December 1851.

Fred Barnard's illustration of Dora Spenlow during her illness, in the 1872 Household Edition of David Copperfield. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

On this occasion, Dickens named the ill-fated child not after an author or family member, or pillar of the Victorian establishment, but after one of his own characters — the beautiful but ineffectual Dora Spenlow in David Copperfield. The novel was published in monthly instalments between May 1849 and November 1850, and Dickens's youthful protagonist falls in love with Dora at first sight. However, she is quite unable to manage her role as wife, and never recovers from a miscarriage.

The real-life Dora was always sickly. Biographers such as John Forster, Michael Slater, Claire Tomalin, and Peter Ackroyd all note that Charles Dickens arrived back in London on 14 April 1851, after installing his ailing wife at the health resort of Malvern, at the foot nf the Malvern Hills in Worcestershire. He had returned hastily to town in order to preside over the annual dinner of the General Theatrical Fund. Before leaving for the banquet, Dickens played briefly with the little girl, who seemed in good spirits and good health. However, just minutes before he began making his speech, Dora went into convulsions and died. In his two-volume Life of Charles Dickens (1871), Forster recounts how he gave Dickens the news, and how he received it:

Half an hour before [Dickens] rose to speak I had been called out of the room by one of the servants from Devonshire-terrace to tell me his child Dora was suddenly dead. She had not been strong from her birth; but there was just at this time no cause for special fear, when unexpected convulsions came, and the frail little life passed away. My decision had to be formed at once; and I satisfied myself that it would be best to permit his part of the proceedings to close before the truth was told to him. But as he went on, after the sentences I have quoted, to speak of actors having to come from scenes of sickness, of suffering, aye, even of death itself, to play their parts before us, my part was very difficult. [II: 87]

John, Dickens's father, had recently died (31 March) and been buried at Highgate on 5 April, so that the shock of the child's death just nine days later was all the greater for the writer. Slater reproduces the sensitive letter in which Dickens communicates with his ill wife, carefully preparing Catherine for the worst (which, of course, has already occurred):

Little Dora, without being in the leas pain, is suddenly stricken ill. She awoke out of a sleep, and was seen, in one moment, to be very ill. Mind! I will not deceive you. I think her very ill.

There is nothing in her appearance but perfect rest. You would suppose her quietly asleep. But I am sure she is very ill, and I cannot encourage myself with much hope of her recovery. I do not — why should I say I do, to you my dear! — I do not think her recovery at all likely.

I do not like to leave home. I can do nothing here, but I think it right to stay here. You will not like to be away, I know, and I cannot reconcile it to myself to keep you away. Forster with his usual affection for us comes down to bring you this letter and to bring you home. But I cannot close it without putting the strongest entreaty and injunction upon you to come home with perfect composure — to remember what I have often told you, that we never can expect to be exempt, as to our many children, from the afflictions of other parents — and that if — if — when you come, I should even have to say to you "our little baby is dead," you are to do your duty to the rest, and to shew yourself worthy of the great trust you hold in them. [Dickens and Women, 131]

Catherine did, as Dickens wrote to Bulwer Lytton a few days later, accept the death with tranquil resignation, but the associations of the house opposite Regent's Park must have made it seem imperative to Dickens that he get his wife to a happier, more salubrious setting. Consequently, they returned to their summer place, Fort House, at Broadstairs on the Channel, and later that year made Tavistock House their new (and final) London home together. Dora's funeral occurred on April 18.

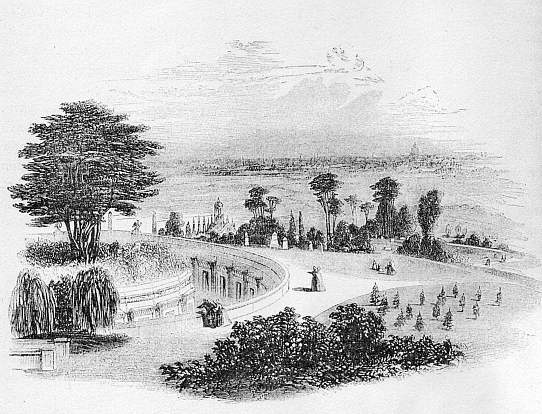

Highgate's Western Cemetery in these early years. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The inscription on her tombstone in Highgate Cemetery West, a spot which Dickens specifically chose for its bird-song and panorama of London spread out below, reads: "Dora Annie, the ninth child of Charles and Catherine Dickens, died 14th. April 1851, aged eight months." She is buried in the same grave as her mother beneath a marker that bears the names of two of her brothers who died abroad decades afterward: Walter, who died in Calcutta in 1863, and Sydney, who died and was buried in the Indian Ocean in 1872.

As Slater points out in his biography of Dickens, the incident demonstrates the increasingly important role that Forster was to play in the novelist's life over the next two decades, fitting him to be the one best suited to serve as Dickens's first biographer. AS for Dickens' writings, Dora's death shocked her father, who swore that never again would he name one of his children after one of his characters: he was determined to keep his own children separate and distinct from the children of his imagination. His breakdown after the arrival of a stunning floral tribute several nights after Dora's death, and this artistic resolution, both seem to suggest that, in an odd way, he somehow felt responsible for the child's sudden death.

Note: Many thanks to Christine Whittemore for sending in a correction to this page.

Related Materials

- Catherine Dickens (née Hogarth), 1816-79: Dickens's Wife and Travelling Companion

- A Chronology of Dickens's Life

- The Children of Charles Dickens and Catherine Hogarth Dickens, 1837-52

- Major Biographies of Dickens — a Critical Overview

- Where the Dickens: A Chronology of the Various Residences of Charles Dickens, 1812-1870

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1999.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. 2 vols.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Charles Dickens. Dickens' Bicentenary 1812-2012. San Rafael, California: Insight, in association with the Charles Dickens Museum, London, 2012.

Schlicke, Paul (ed.). The Oxford Readers's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009.

Slater, Michael. Dickens and Women. London and Melbourne: J. M. Dent, 1983.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. New York: Penguin, 2011.

Created 16 September 2019

Last modified 16 August 2022