Country Houses, New and Improved

While urban and suburban areas were becoming more and more built up, the face of rural Britain was changing as well. The Enclosure Acts of the mid-eighteenth century onwards had made the landed gentry more "landed" than ever. Now, many of them were thriving on the profits "from mines, mills and factories (often built on their country estates); from railways, canals, docks and shipping; or from investments in stocks and shares and rent from urban developments" (Yorke 72). They were restoring, extending or even completely rebuilding their country estates, giving them fashionable historical or continental features. Meanwhile, those whose fortunes were newly flourishing in business and industry were also setting themselves up in the countryside to consolidate or enhance their status. "So much new money in both new and old families tended to make the country-house world competitive," writes Mark Girouard (Life in the English Country House 268). The competition was partly about size; but style was just as important. Whether spending old money or new, the proud possessors of these estates wanted to show off their own taste in architecture. Most employed top-level architects, but, despite the increasing professionalism of the craft, a few decided to design their own homes. The results could sometimes leave their visitors not so much impressed as positively speechless. Those estates that remain, mostly as National Trust attractions, conference centres, educational establishments and so on, can still take us by surprise today, as can the smaller structures dotted round these estates — curious outbuildings generally in the same style as the main houses. Not all of them are considered important by architectural historians, but taken together they add immeasurably to the interest and charm of our countryside.

Updating a Family Seat

Charles Scarisbrick is a prime example of a landowner who benefited from the use of his land for mining and property development. A descendant of generations of Catholics, he was also a patron of the arts (particularly of the apocalyptic painter John Martin) with a particular taste for Rembrandt etchings and antique woodcarvings. To remodel his house, Scarisbrick Hall, he selected an up-and-coming Catholic with a passionate and passionately voiced belief in the Gothic: A. W. N. Pugin. The young Pugin worked on the house for about eight years from 1837 onwards, improving on its already Gothic features, and adding a wonderful medieval "Great Hall" complete with minstrels' gallery, entrance porch and later a delicate lantern. When this and the already elaborately ornamented reception rooms adjacent to it (the Oak Room, the Kings Room and the prominent Red Drawing Room) were hung with paintings and etchings, and fitted with Scarisbrick's huge collection of imported church altarpieces, carved canopies and so forth, the atmosphere must have been extraordinary. This wing of the building was balanced in a picturesque rather than formal sense by a "Business Room" and an attractive clock tower to the east (a forerunner of the one that houses Big Ben at Westminster). These however were demolished by Charles's sister Anne after his death in 1860, and the tower replaced by a much heavier and taller one designed by Pugin's son Edward. This had the effect of turning the elder Pugin's more quietly romantic creation into a Gothic extravaganza. The house as it stands now, with its ornately carved bay windows, parapets, rooftop sculptures, turrets, dainty pinnacles and the great beacon of a tower at its far end, has been aptly described as "a curious chronicle of nineteenth-century taste" (Hill 183), charting specifically "the move from early Victorian richness to mid-Victorian fantasy" (Girouard, The Victorian House, 118).

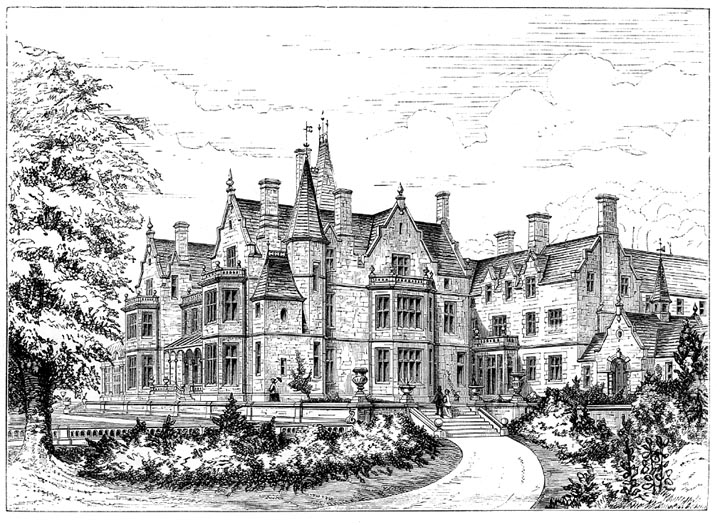

Around the time Scarisbrick Hall was being altered again, another old family seat was being remodelled by one of Pugin's pupils. The Welsh diocesan architect John Prichard, who had recently overseen the restoration of Llandaff Cathedral, was at work on Ettington (previously "Eatington") Park near Stratford-upon Avon in Warwickshire. As so often, the house had undergone various changes through the centuries, probably having been rebuilt completely in 1641, and certainly having been altered since then. Now, in 1858-62, Prichard took off the outside walls and built them up again around the interior, raising the height of the building, adding turrets, tall chimneys, a chapel and so on, but managing to do so without making it look pretentious or extravagant. As a result, Ettington Park has one of the pleasantest of all High Victorian country house exteriors. It combines satisfying lines with attractively modulated polychromy created from several different colours and textures of stone, and has rich carvings and sculptural adornments by the master stone-carver Thomas Earp. This was the same craftsman who worked for G. E. Street at St James the Less in London, and was responsible for the elaborate replacement Eleanor Cross outside Charing Cross on the Strand. Clearly, no expense was spared at Ettington. All the craftsmanship was of the highest order. The house turned out to be more continental in flavour than Scarisbrick Hall, a lovely example "of the French and Italian Gothic style of architecture promoted by John Ruskin" ("The History of Ettington Park and the Shirley Family.")

Wotton House in Surrey was refaced at a slightly later date and shows a different approach again. This was the seat of the Evelyn family: the seventeenth-century diarist John Evelyn was born there and had loved the old, gently rambling manor house. Following the trend of the time, his descendant William Evelyn decided to remodel it in the 1860s. With an example of Pugin's work just down the road at Albury Park, he chose as his architect the Surrey-based Henry Woodyer, who had probably had some experience of working with Pugin. Woodyer was well known by now for his own churches and country house restorations. He stayed close to the original plan of the house, rebuilding the east wing and refacing the front of the house in a "hard Tudor style" (Nairn and Pevsner 542-43). The main addition, presumably the east wing, was completed in 1864 (Girouard, The Victorian House, 442), but work continued long after that: a stone plaque commemorates its completion in 1877. This house reflects a different development of the Gothic — towards a later Tudor version of it rather than earlier or continental varieties. Only a few glimpses of the original manor house remain now, and those mostly inside and at the rear. Nevertheless, apart from the extension of the orangerie, the end result from the same vantage point over the grotto looks surprisingly similar to the house drawn by John Evelyn in 1653.

Buying and Doing up an Old Country Estate

Those who could newly afford to buy up old estates also set out to improve them. An excellent example here is William Gibbs, whose vast fortune was built on guano and nitrate for fertilisers. He may not have been a member of the aristocracy, but he did come from a good solid background of "small squires, country bankers, merchants and professional men" (Girouard, The Victorian Country House, 243). Inevitably, therefore, he wanted to own a substantial country property.

He bought Tyntes Place near Bristol in 1843, and employed first John Norton and then Woodyer to remodel it into Tyntesfield, a full-blown Gothic stately home complete with a chapel by the even more distinguished architect Arthur Blomfield. Most of the work on the main house was done in the 1860s by Norton, who had been a pupil of Benjamin Ferrey and, like Woodyer, was responsible for a number of other country houses. With William Cubitt as the builder, he extended the house both outwards and upwards with a picturesque mix of towers, turrets, spires and spirelets. Woodyer's turn came a good bit later, in the 1880s, and consisted of alterations rather than additions, perhaps the most important of which was to open up more space for a large and airy dining room. Now a Grade 1 listed building, Tyntesfield is one of the handful of Victorian country houses recognised as truly important. Girouard discusses it as some length in the revised edition of The Victorian Country House, giving special praise to its beautiful interior woodwork (for a virtual tour, see the note below).

The interior seems to have been the main focus of the wealthy banker and lawyer Lachlan Mackintosh Rate, who bought Milton Court in Dorking, Surrey, in 1863. Not far from Wotton, this estate had been granted to George Evelyn by Queen Elizabeth, and had belonged to the Evelyn family until about 1830. Some restoration work had already been carried out, and it is not known for sure when the picturesque rounded gables were added. What is certain is that Rate's architect William Burges not only made some additions in the 1870s, but also transformed it inside, adding almost twenty new rooms and turning the whole place into a work of art.

Others bought quite small but nicely situated places in rural areas and added wings and fashionable Victorian features to them, so that their purchases evolved into country houses as against simply houses in the countryside. The Colquhoun family, for instance, bought up an eighty-acre farming estate in Kent in 1848 and extended the main house on it, adding fashionable embellishments such as bay and oriel windows and mock-Tudor chimneys, along with over-sized baronial stepped gables. The latter may be explained by the family's Scottish landowning background. The end result must have been impressive enough, because the house was later bought by Winston Churchill. In fact, this was Chartwell (shown above), of which the Churchills were extremely fond. They soon had some of the more extravagant features toned down or removed, along with a great deal of ivy; but the house still flaunts its Victorian gables, making it look somewhat "galleon-like" (Buczaki 125).

Sometimes, of course, aspirational new owners took on more than they could really manage. A certain Henry Hurrell Esq., probably from a local farming and corn-dealing family, bought Madingley Hall in Cambridgeshire in 1871. Three years later he demolished the east end of the north wing, but he only put in a one-storey replacement — a drawing room. In 1905 the next owner found the building in a state of disrepair, and had to embark on a massive rebuilding project of his own.

Building a New Country Estate

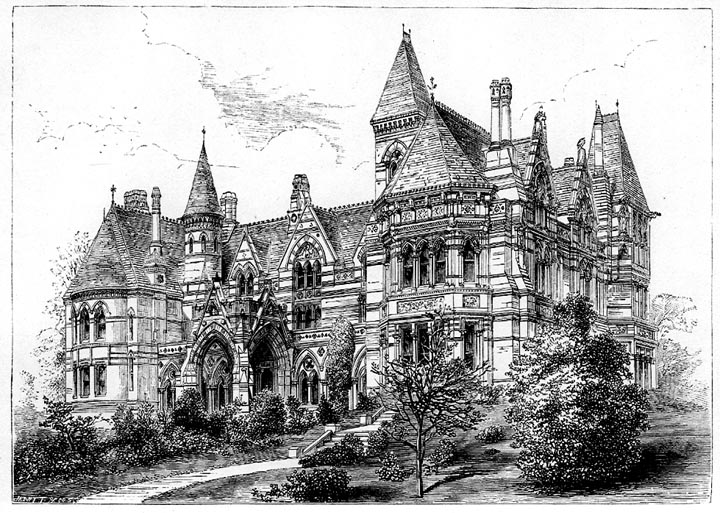

Then there were those who built impressive country residences entirely from scratch. Orchardleigh Park in Somersetshire, once the family seat of the Chamneys (or Champneys) family, the rich conveyancer William Duckworth built a prestigious new country house in the mid-1850s to designs by Thomas Henry Wyatt. The younger brother of Matthew Digby Wyatt, who worked on the India Office with Sir George Gilbert Scott, T. H. Wyatt himself "had one of the largest country house practices of the period," and was second only to Scott in the number of buildings he produced. He designed Orchardleigh in the style then in favour, a "combination of Elizabethan and French styles often described [aptly enough] as 'nouveau-riche'" (Holder 45-46). Another brand new country house, Cloverley Hall in Ightfield, Shropshire, was designed a little later by W. E. Nesfield in what has been called a "new maturer phase in the [Gothic] Revival" (Newman and Pevsner 219). Built in 1864-70 for the wealthy Liverpudlian banker John Pemberton Heywood, it showed a greater degree of sophistication, though it seems unfair to describe it as "one of the first Victorian houses to incorporate a great hall" ("Cloverley Hall") — Pugin had built the hall at Scarisbrick a good twenty years before. This house was rebuilt in 1926, but the service range, culminating in a tower inspired by the French architect Viollet-le-Duc, as well as some of the estate buildings (including a boathouse and a village hall), still survive.

In some instances, a new country house evolved more gradually. In the north of England, the inventor and armaments magnate Lord Armstrong had a big house Cragside built on the spot where he originally had a small hunting lodge; then he enlarged this too. The fact that this house developed on its craggy hillside rather than just sprang up seems especially appropriate because the architect for the final phase was Richard Norman Shaw. Shaw felt that houses should grow organically: he had already built the influential Leys Wood in Groomsbridge, Sussex, for his well-to-do cousin in the shipping line, and the result here in Northumberland was another "early masterpiece" (Durant 174), in a style variously described as Old English, Domestic Revival or Arts and Crafts.

The Amateur Architect

As for those who opted to update their country houses themselves, none was more imaginative both in design and execution than the Earl of Lovelace. Lovelace was the son of Baron King of Ockham, in the heart of rural Surrey. He held many estates in the county, and in about 1846 decided to adopt nearby East Horsley Place as his main seat. This house had been completed by Sir Charles Barry in an unexceptional mock-Elizabethan style in 1834. Being "an amateur and, as far as can be ascertained, self-taught engineer" (Tudsberry-Turner 8), the Earl set to work to improve it himself. In 1847 he added a tall stuccoed tower and a big banqueting room. For the latter he used a process of steam heat to bend the roof trusses — a method which he explained in a paper given in 1849 to the Institution of Civil Engineers, of which he had become an Associate. The method was praised by none other than Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Now the Earl really began to spread his wings, adding another tower of flint and polychromatic brick in 1858, and soon afterwards elaborate cloisters leading to a ribbed and vaulted chapel positively brimming with polychromy. Guests were bowled over by the house, now grandly renamed Horsley Towers: Matthew Arnold called it "fantastic" (308). Superlatives still seem to be in order here. Girouard comments on the house's "extraordinary embellishments" (The Victorian Country House, 410), while even Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner admit that "the entry up the main drive must be one of the most sensational in England" (204); they use the same adjective as Arnold — "fantastic" — about its details, such as the use of drainpipes as shafts in the cloisters (205). Nor do surprises end with the house itself. The Earl was fascinated by building materials, and had won a medal for brickmaking at the Great Exhibition. Once the house was completed, he set about transforming the whole village of East Horsley. Much of it, including the local butcher's shop and pub, was built or rebuilt in the 1860s in his own distinctive style, with flint facings and polychromatic brick bandings. No landowner could have made it clearer that this was his personal domain.

More daring still, and more engagingly documented, was Charles Buxton, who decided to build his own country house from scratch. He bought a piece of land close to Cobham in the north of Surrey, and built the Foxwarren estate on it. From the beginning, he entered into the spirit of the thing enthusiastically, learning all he could about architecture, and even submitting a design for new government offices; he managed to win sixth prize in the competition. Much encouraged, and much taken with the Gothic, "he caught at every opportunity of designing a lodge or a farmhouse or any other building" and eagerly embarked on his Surrey project: "I think our house will be singularly pretty and original," he enthused, on one occasion writing in his journal, "Enjoying my thoughts, chiefly on architecture. That is what I turn to for enjoyment — planning picturesqueness" (qtd. in Nairn and Pevsner 597-98). Like the architect at Chartwell, he had a penchant for stepped gables; he also decorated the brickwork copiously with polychrome diapering. On the rest of his land he built two dinky matching lodges, a model farm, and a watch tower. The result has been harshly criticised. Girouard finds the red brick and terracotta of the main building, unrelieved by stone dressings, "unpleasantly hot," and he echoes Nairn and Pevsner's description of the heavily gabled farm as "nightmarish" (The Victorian House, 406-07), without adding more encouragingly, as they do, that it is "possibly the extreme example in the country, and well worth seeing" (246).

Many other owners of country estates sprinkled picturesque outhouses in their grounds. For example, one of the ways in which Sir Walter Farquhar, the new owner of Polesden Lacey, made his mark on his own Surrey estate in the 1850s was to have a picture-perfect Garden Cottage built in the grounds for his head gardener. Complete with crooked, fairy-tale chimney, it was totally out of keeping with the splendidly neo-classical main house which Thomas Cubitt had built for the previous owner. But no doubt that was the point — to create something different. Fashions had changed. Besides, the rustic style was surely more suitable for a gardener's cottage.

The Fate of the Victorian Country House

Suitability, or "fitness for purpose" in the modern idiom, would gradually become more of an issue. Victorian country houses were both large and complicated. This was partly because the household itself was large: Cloverley Hall, for example, accommodated a fleet of twenty-five servants, and this would have been quite a modest staff. What was more, the members of the household all had their own roles and functions, and required their own space. Privacy was a priority: Kerr says, "whatever may be their mutual regard and confidence as dwellers under the same roof, each class is entitled to shut its door upon the other and be alone" (68). Then there were the male/female boundaries: one thinks of Mrs Rate's ultra-feminine Flower Room at Milton Court, or the heavily trophy-hung billiard room at Tyntesfield. Girouard suggests that the new "mechanical services" that were being invented also contributed to the size of the houses (see The Victorian Country House 27-8). Cragside again comes to mind here, with its banks of heating pipes, and its pioneering hydraulic lift. Houses planned with such considerations in mind have been dismissed rather unkindly as "obsolete brick and stone monsters" (Gash 690). The truth is that they soon did become "obsolete," at least as far as their original purpose was concerned. Families were shrinking, less people were going into service, and the houses themselves were proving impractical and costly to maintain. Then in 1894 the forerunner of inheritance tax, death duty, was imposed. This was a major blow to the landed gentry. Many houses were sold and demolished, their memories lingering on only in the names of later housing developments on their land. Others were converted for some kind of multiple occupancy, which of course affected their interiors, even if some important features were preserved. Of the houses mentioned above, Cloverley, Ettington Park, Horsley Towers, Orchardleigh and Wotton House are now hotels and/or conference centres; Albury provides retirement accommodation; Milton Court is used by an insurance company, its beautiful Burges ceilings looking down on board-meetings; and Madingley Hall and Scarisbrick Hall are both used for educational purposes. The remainder — Chartwell, Cragside, Polesden Lacey, and Tyntesfield — are luckier, because they have passed into the hands of the National Trust, and their interiors as well as exteriors have been preserved and restored.

People enjoy visiting these houses, and even the ones now in use as hotels, schools and so on often open their doors or gardens (or both) to visitors on special days, or upon request. Their immense historical and architectural value is now much more fully recognised, thanks to a number of high-profile campaigns to save individual houses for posterity: Tyntesfield was acquired for the nation by the National Trust as recently as 2002. Probably their main attraction, though, is their human interest. For only in their homes can we get a real sense of how the wealthiest of our ancestors lived their daily lives. A really well-preserved estate like Tyntesfield is, as James Miller says, "a private kingdom" which sheds light on every aspect of their original owners' activities, from their domestic arrangements to their intellectual and cultural tastes, and even their business and religious practices — as well as being "a reflection of English life, generation by generation" (177). The English countryside would be so much the poorer without these very special houses.

Questions

Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner find it sad that "such an inventive engineering talent" as the Earl of Lovelace's should have "thought of architecture in the typical C 19 way as something to be added on to structure, not to grow inevitably out of it" (205). To what extent is this a fair comment on Victorian architecture in general?

As for country houses, how far was the Earl of Lovelace's approach "typical" of its period? It might be helpful here to contrast his additions to Horsley Towers with the roughly contemporary enclosure of the inner courtyard of the Trevelyan's family seat, Wallington, by the architect John Dobson in 1852-53. What were the different purposes of these two architects?

Henry Hetherington Emmerson (1831-1895), who had been taught by the northern Pre-Raphaelite William Bell Scott, painted a finely detailed portrait of Lord Armstrong of Cragside sitting in his inglenook fireplace. Wearing a comfortable suit, he is reading a newspaper, with two dogs at his slippered feet. Beside him are two panels of stained glass by William Morris, and over the fireplace are inscribed the words, "EAST OR WEST HAME'S [home's] BEST." Everything in the picture, from Lord Armstrong's wooden inglenook seat to the fireplace surround and the coal scuttle, is beautifully worked. What does a picture like this tell us about the values attached to the Victorian country house?

Last modified 24 November 2023