Introduction

ach of the topics, tropes, and themes that will be discussed in this chapter relates differently to our reference paradigm, the shipwreck on the journey of life, and each has something of interest to tell us about modern iconology. The Deluge, a literal event recorded in the Old Testament, exemplifies a supposed fact that the Judaic and Christian traditions have endowed with paradigmatic significance. According to the Book of Genesis, God sent His flood to punish man for his evil, and therefore the Deluge serves as the biblical equivalent to the notion of the shipwreck as punishment. In both situations, God sends water to engulf the guilty. At the same time that Genesis provides a culturally paradigmatic instance of the Lord's punishing guilty human beings by using the forces of nature to do so, it also offers a corollary one of His preserving the faithful. Since the Middle Ages the ark that saved Noah and his family has been taken by believers as a divinely intended type of the Christian church, or Christ Mystical: it indicates, say the exegetes, that God placed in history an example of the principle that one is saved only by joining with others in the Church of Christ, a church which, like the ark itself, finds itself besieged by destructive forces from without but which God ultimately preserves and employs to lead man to new life. The accepted meanings of ark and Deluge, however, become subverted in the nineteenth century, as many begin to question the nature of divine Justice. Since the Deluge stands as such an explicit instance of divine vengeance, its subversion requires a particularly explicit questioning of Christianity. Considered from the point of view of the shipwreck paradigm, then, the Deluge, in many of its nineteenth-century artistic and literary manifestations, represents the post-Christian subversions an unambiguous biblical event traditionally taken as paradigmatic.

ach of the topics, tropes, and themes that will be discussed in this chapter relates differently to our reference paradigm, the shipwreck on the journey of life, and each has something of interest to tell us about modern iconology. The Deluge, a literal event recorded in the Old Testament, exemplifies a supposed fact that the Judaic and Christian traditions have endowed with paradigmatic significance. According to the Book of Genesis, God sent His flood to punish man for his evil, and therefore the Deluge serves as the biblical equivalent to the notion of the shipwreck as punishment. In both situations, God sends water to engulf the guilty. At the same time that Genesis provides a culturally paradigmatic instance of the Lord's punishing guilty human beings by using the forces of nature to do so, it also offers a corollary one of His preserving the faithful. Since the Middle Ages the ark that saved Noah and his family has been taken by believers as a divinely intended type of the Christian church, or Christ Mystical: it indicates, say the exegetes, that God placed in history an example of the principle that one is saved only by joining with others in the Church of Christ, a church which, like the ark itself, finds itself besieged by destructive forces from without but which God ultimately preserves and employs to lead man to new life. The accepted meanings of ark and Deluge, however, become subverted in the nineteenth century, as many begin to question the nature of divine Justice. Since the Deluge stands as such an explicit instance of divine vengeance, its subversion requires a particularly explicit questioning of Christianity. Considered from the point of view of the shipwreck paradigm, then, the Deluge, in many of its nineteenth-century artistic and literary manifestations, represents the post-Christian subversions an unambiguous biblical event traditionally taken as paradigmatic.

The figure of Odysseus, in contrast, exemplifies ironic and subversive intonations of a secular literary or mythic personage. One of the prime facts about this cunning, much-traveled, much-suffering [133/134] man who has descended to us from the ancient, pre-Christian past is that he is the man who would return home. Therefore, the Homeric hero has many similarities to St Augustine's figure of man voyaging to his heavenly home, for both Odysseus and Or must return to their points of origin to become themselves fully.

Like the Deluge, the rainbow receives a specific paradigmatic value from Genesis, which relates that the Lord Himself declared that it would always be a covenant-sign, the emblem of His promise to man. Unlike the Deluge itself, which can never occur literally again, the rainbow placed in the heavens by God appears both in biblical and in contemporary history. It therefore provides problems and possibilities for the artist who would employ it. The rainbow also provides the iconsologist with an opportunity to distinguish the different ways that images, situations, and figures function in pictorial and literary arts.

The Deluge transformed (1): The Christian Tradition, Biblical Interpretation, and Literature

[In] the six hundredth year of Noah's life, in the second month, the seventeenth day of the month, the same day were all the fountains of the great deep broken up, and the windows of heaven were opened.

And the rain was upon the earth forty days and forty nights....

And the flood was forty days upon the earth; and the waters increased and bare up the ark, and it was lifted above the earth. And the waters prevailed, and were increased greatly upon the earth, and the ark went upon the face of the waters.

And the waters prevailed exceedingly upon the earth, and all the high hills, that were under the whole heaven, were covered. Fifteen cubits upward did the waters prevail; and the mountains were covered.

And all flesh died that moved upon the earth, both of fowl, and of cattle and beast, and of every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth, and every man: All in whose nostrils was the breath of life, of all that wash dry land , died.

And every living substance was destroyed which was upon the face of the ground, both man, and cattle, and the creeping things, and the fowl of the heaven; and they were destroyed from the earth: and Noah only remained alive, and they that were with him in the ark.

And the waters prevailed upon the earth an hundred and fifty days. [Genesis, ch. 8; [134/135] ]

[not in print edition] John Martin. The Deluge. 1834. Oil on canvas. 66 x 102 inches. This painting of Noah's flood is one of several that he did on the subject of floods destroying guilty human being, including The Delivery of Israel out of Eygpt (1825), The Destruction of Pharoah's Host (1830), Sodom and Gomorrah (1832), and The Destruction of Tyre (1840).

ike God s drowning the Egyptian host in the Red Sea, the Deluge offers a definite, unmistakable instance of divine punishment, and the ark that preserved Noah and his family offers a similarly

unmistakable install e of divine protection. This connection between preserving the good and destroying the evil provides a structure that recurs frequently in biblical history. As Patrick Fairbairn, the great nineteenth-century student of hermeneutics, explains in The Typology of Scripture,

ike God s drowning the Egyptian host in the Red Sea, the Deluge offers a definite, unmistakable instance of divine punishment, and the ark that preserved Noah and his family offers a similarly

unmistakable install e of divine protection. This connection between preserving the good and destroying the evil provides a structure that recurs frequently in biblical history. As Patrick Fairbairn, the great nineteenth-century student of hermeneutics, explains in The Typology of Scripture,

This principle of salvation with destruction, which found such a striking exemplification in the deluge, has been continually appearing anew in the history of God s dealings among men. It appeared, for example, at the period of Israel's redemption from Egypt, when a way of escape was opened for the people of God by the overthrow of Pharaoh and his host; and again at the end of the return from Babylon, when the destruction of the enemy and the oppressor broke asunder the bands with which the children of the covenant were held captive. But it is in New Testament times, and in collection with the work of Christ, that the higher manifestation of the principle appears. . . . In Christ, however, the very foundations of evil from the first were struck at, and nothing is left for a second beginning to the cause of iniquity. ["Noah and the Deluge"]

The Genesis narrative of the Flood, which thus contains one of the central principles of history, also functions typologically in several ways. First of all, this instance of divine punishment serves as a type of later ones. Indeed, according to John Keble, who was one of the founders of the Oxford Movement, "Even if our Lord had not told us. . . we should scarce have failed to perceive how nearly we are concerned in this fearful picture. The history of the world before the Flood is but too nearly a type and shadow of our own history, and our own condition in God's sight ("As it was in the days of Noah," Sermons, vol. 4). Keble of course takes the title of his sermon from Luke 17: 26-7, which provides scriptural sanction for thus taking the Deluge typologically:

And as it was in the days of Noah, so shall it be also in the days of the Son of man. They did eat, they drank, they married wives, until the day that Noah entered into the ark, and the flood came and destroyed them all.

[135/136] With such biblical sanction or authentication for typological readings exegetes easily found other prefigurative elements in the Genesis story. Fairbairn, for example, explained that Noah himself "was the type, but no more than the type, of Him who was to come — in whom the righteousness of God should be perfected" ("The New World and its Inheritors"). In addition, the ark, that obvious vessel of salvation serves as a type of the Church of Christ. Therefore, says J. C. Ryle, the great Evangelical Anglican Bishop of Liverpool, in his commentary on Luke 17: 26-3 7, "We must come out from the world and be separate. . . . We must flee to the ark like Noah" (Expository Thoughts on the Gospels). The first Epistle of St Peter 3: 21 also taught Christians to take the Deluge as a type of Baptism, and High Church Anglicans, such as Isaac Williams, often emphasize this particular typological reading but by far the most common eighteenth- and nineteenth-century one is that the ark is a type of the Church of Christ. As Thomas Scott's immensely popular Bible commentary, which was found in many English and American Protestant homes, joyfully exclaims:

Happy they, who are part of Christ's family, and safe with him in the ark! They may look forward without dismay, rejoice in the assurance, that they shall triumph, when a deluge of fire shall encircle the visible creation. But, unless we dare to be singular, and renounce the favour, and venture the scorn and hatred of the world: unless we are willing to exercise self-denial and diligence; we can find no admission into this ark. And, even in the ark, while in this world, we shall need faith and patience, and have much to try them. [commentary on Genesis 5: 17-24]

Furthermore, as Bible commentators explain, since the Church of Christ is the mystical body of Him, or Christ Mystical, the ark serves doubly as such a divinely intended prefiguration — first as a type of the Church and second as a type of Christ Himself. Both these ideas appear as commonplaces of Evangelical hymnody. For example, "On the Commencement of Hostilities in America," one of John Newton's Olney Hymns, opens:

The gath'ring clouds, with aspect dark,

A rising storm presage;

Oh! to be hid within the ark,

And sheltered from its rage! [136/137]

In contrast other of Newton's influential hymns use this figure as a means of poetic resolution. "The Hiding-Place" thus begins with the speaker pointing to "the gloomy gath'ring cloud,/ Hanging o'er a sinful land" and warns that "Times of trouble" are upon us. Immediately, however, this hymn reassures the believer that no matter how bad the earthly situation becomes, "they who love his name" have nothing at all to fear. The hymn closes by having Christ Himself use this figure of the ark to comfort those he loves:

You have only to repose

On my wisdom, love, and care;

When my wrath consumed my foes,

Mercy shall my children spare;

While they perish in the flood,

You that bear my holy mark,

Sprinkled with atoning blood,

Shall be safe within the ark.

This pattern of introducing all initial unquiet and insecurity which is then resolved by the appearance of the ark appears in yet another of Newton's hymns, "Rest for Weary Souls," in which the speaker first describes his weakness, sinfulness, and consequent spiritual misery. The third of four stanzas then introduces the type of the ark:

In the ark the weary dove

Found a welcome resting-place;

Thus my spirit longs to prove

Rest in Christ, the ark of grace:

Tempest-toss'd I long have been,

And the flood increases fast;

Open, Lord, and take me in

Till the storm be overpast.

The concluding stanza, which resolves the conflict posed by the hymn, moves ahead to that time the believer finds himself secure In Christ, and, rejoicing in the "wondrous change" he experiences when His Saviour soothes his "troubled mind," he addresses his former fellow sufferers and invites them to join him in the ark: [137/138]

You that weary are like me,

Hearken to the gospel call;

To the ark for refuge flee,

Jesus will receive you all

The ark, which is a type of both Christ and His Church, long offered Christians a paradigm, therefore, of the way that God could preserve them from the Deluge of this world, and the Deluge, offered a figure for a wide range of fearful things and events one wished to escape — divine punishment, one's own sinfulness, an oppressive world, and so on. As John Ruskin reminded his Victorian readers in the chapter on "Torcello" in The Stones of Venice, "in the minds of all early Christians the Church itself was most frequently symbolized under the image of a ship, of which the bishop was the pilot." Ruskin, who is engaged in explaining how Venice had its beginnings on those outlying islands settled by refugees from the mainland, next instructs his reader to 'consider the force which this symbol would assume in the imaginations of men' to whom the spiritual Church had become an ark of refuge in the midst of a destruction hardly less terrible than that

from which the eight souls were saved of old, a destruction in which the wrath of man had become as broad as the earth and as merciless as the sea, and who saw the actual and literal edifice of the Church raised up, itself like an ark in the midst of the waters.

Therefore, says Ruskin, who tries to convince his contemporaries that Venice stands as a type and warning for Victorian England, if one wishes to 'learn in what spirit it was that the dominion of Venice was begun, and in what strength she went forth conquering and to conquer," one should not seek in her arsenals, armies, and palaces. Rather, one must climb to where the Bishop of Torcello used centuries before, to sit,

and then, looking as the pilot did of old along the marble ribs of the goodly temple-ship, let him repeople its veined deck with the shadows of its dead mariners, and strive to feel in himself the strength of heart that was kindled within them.

Their reliance on God, their faith, says Ruskin, make the Venetians [138/139] great — and when they fell away from that faith, they left the ark and were destroyed. If England, he warns in the very first paragraph of The Stones of Venice, neglects to learn from the example of its predecessors, his nation and his people 'may be led through prouder eminence to less pitied destruction.'

Unfortunately, even at the time that Ruskin was writing The Stones of Venice, he was beginning that long, painful process which resulted, finally, in his abandonment of his childhood faith. The man, in other words, who had so emphasized that societies could only survive by making the worship of God their ark, found, soon enough, that he could find no God, and no ark. Before acquiring a much qualified belief more than a decade later, he joined that company of "melancholy Brothers" whom James Thomson described in The City of Dreadful Night "battling in black floods without an ark" (sec. 14). Such "melancholy Brothers," who find themselves in the condition of castaways, represent one of the two major transformations the Deluge-figure receives — the disappearance of the ark. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, those who, like Wordsworth, retain their Christian belief employ the scriptural type in its old sense. In The Excursion, for example, the poet has one of his characters assert that at the baptismal font the child is

received

Into the second ark, Christ's church, with trust

That he, from wrath redeemed, therein shall float

Over the billows of this troublesome world

To the fair land of everlasting life. [bk 5, 11. 281-5]

The Deluge transformed (2): Romanticism and the Massacre of the Innocents

For those who do not believe, however, there is no ark, and they find themselves alone while the waters rise. Byron thus contemplates the history of Napoleon in the fourth canto of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage and sees "An universal Deluge, which appears/ Without an ark for wretched Man's abode,/ And ebbs but to reflow!" (ll. 826-28). Byron implores "Renew thy rainbow, God!" (l. 828), but he has no faith that He will renew His covenant with man, and in Byron all the rainbows are illusive and delusive. The rainbow that comes after the storm in Don Juan thus brings no safety and salvation for the shipwrecked men. In fact, it stands as a paradigm of capricious flux and not any eternal Christian covenant; and appropriately when a white bird appears, it is no dove of peace, hope, and grace, but potential food for the starving men: [139/140]

And had it been the dove from Noah's ark

Returning there from her successful search

Which in their way that moment chanced to fall

They would have eat her, olive-branch and all. [canto 2, st. 95]

In the Byronic conception of things, nature smiles while men perish and men, not surprisingly, grant no credence to Covenants of grace and arks of salvation.

The other major transformation of the Deluge, which takes the form of questioning its justness and morality, is even more radical. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, even this most definite, most unmistakable example of devil punishment of guilt man had become problematic and ambiguous. Benjamin West's wash drawing of The Waters Subsiding After the Deluge (c. 1791, Boston Museum of Fine Arts) introduces us to the common Romantic and post-Romantic vision of this event. In the immediate foreground the heaped bodies of men, women, and children command our attention; and looking past them, we perceive the ark come to rest on high ground beneath an overarching rainbow. The artist's thrusting forward the bodies of the slain, who in death bear no trace of any evil nature or action, creates a powerful image of the aftermath of the Deluge, which its meaning becomes intensely problematic The very presence of the rainbow, a commonplace type of Christ and the new covenant of grace, makes the entire scene appear ironic.

The Deluge by Francis Danby ARA, 1793-1861. Oil on canvas, 2845 x 4521 mm. Exhibited 1840. Accession number: T01337. Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1971. Click on image to enlarge it.

Francis Danby's magnificent and terrifying Deluge (1837-40, Tate Gallery) makes the problematic nature of this event even more obvious, for rather than allowing us to stand emotionally outside the events and Judge the supposedly guilty who perish, the canvas forces us to sympathize with these victims of fate. Danby's representation of the Flood thus subverts its traditional religious meaning in two ways. First of all, making a recognition that became increasingly common in the Victorian period, Danby places major pictorial emphasis upon the fact that the innocent are killed. As the protagonist of J. A. Froude's The Nemesis of Faith (1849), who explains his loss of belief, points out "The sucking children of the unchosen were not saved in Noah's flood." The painter also shows us terrified dying children, thus making us doubt the ethical nature of such an event and the God who prompted it. In fact, moral revulsion against the cruelty of both such instances of divine punishment in history and the doctrine of eternal damnation played a major role in the mid-nineteenth-century crisis of belief. As Josef L. Altholz argues in "The Warfare of Conscience with Theology," "The issue on which the intensity of Victorian religion first began to turn inward on itself was not an external challenge of science or criticism, but a felt conflict between the morality which evangelicals have cultivated and the theological doctrines which they taught."1

Whether or not leading nineteenth-century artists consciously took art in such a spiritual conflict, their works present the Flood from the vantage-point of one who has ethical objections to the usual interpretation of it as an instance of just punishment. Danby, for example, not only makes the common point that God destroyed innocent children but he also subverts Christian conceptions of the Flood by emphasizing the selflessness and even heroism of the victims. We thus find none of the savagery one might expect when maddened men and animals strive desperately to save themselves. No mothers loose their hold on loved ones to secure their own safety; no fathers hurl children from higher grounds to save their own lives. Instead, we have a somewhat sentimentalized vision of all too sympathetic suffering human beings trying wherever possible to save one another.

In this emphasis the painting differs markedly from most earlier — and a few contemporary — representations2 of the Deluge and the Last Judgment, such as those by the Northern Renaissance painters, which stress the sinfulness of the sufferers. To be sure, there were painters of the Renaissance and after who sympathetically depicted the victims of the Flood; and since preachers in word and paint often emphasized that those God punished in the Deluge were not entirely evil, it was therefore quite orthodox to show these victims acting with some nobility. The artist

was on sure theological ground when he tried to make the spectator identify with these earlier objects of divine wrath because such identification made their punishment immediately relevant. Poussin's Winter — in the Louvre cycle of The Four Seasons (1660-64) exemplifies such a generally sympathetic view of the Flood by a pro-Romantic painter who was clearly a devout believer. At the centre of the canvas a man prays, too late, to the raging heavens as his boat capsizes, while at the right a father passes his child down to the safety of a boat. Although Poussin's figures do not act heroically, they do not do anything markedly unheroic or bestial either; and, indeed, were it not for the presence of the ark, which appears in the left distance, and the fact that the other three pictures in this series depict Old Testament subjects, his version of the Flood could be interpreted as any inundation and not the archetypal one.

In this emphasis the painting differs markedly from most earlier — and a few contemporary — representations2 of the Deluge and the Last Judgment, such as those by the Northern Renaissance painters, which stress the sinfulness of the sufferers. To be sure, there were painters of the Renaissance and after who sympathetically depicted the victims of the Flood; and since preachers in word and paint often emphasized that those God punished in the Deluge were not entirely evil, it was therefore quite orthodox to show these victims acting with some nobility. The artist

was on sure theological ground when he tried to make the spectator identify with these earlier objects of divine wrath because such identification made their punishment immediately relevant. Poussin's Winter — in the Louvre cycle of The Four Seasons (1660-64) exemplifies such a generally sympathetic view of the Flood by a pro-Romantic painter who was clearly a devout believer. At the centre of the canvas a man prays, too late, to the raging heavens as his boat capsizes, while at the right a father passes his child down to the safety of a boat. Although Poussin's figures do not act heroically, they do not do anything markedly unheroic or bestial either; and, indeed, were it not for the presence of the ark, which appears in the left distance, and the fact that the other three pictures in this series depict Old Testament subjects, his version of the Flood could be interpreted as any inundation and not the archetypal one.

The Flood by Leandro Bassano. c. 1600, Museo de Arte Ponce, Puerto Rico.

The same generally sympathetic attitude colours Leandro Bassano's much more crowded representation of The Flood, for the victims are portrayed taking care of children and animals, and in the distance there is a particularly moving group in which a woman standing on a roof prays with outstretched arms to heaven. Again, there is nothing either heroic or sentimental about Bassano's conception of the actions of those soon to perish in the Flood; and the fact that many of the figures including the old man in the foreground, are shown still trying to save their worldly goods reveals that the painter places the traditional interpretation upon these biblical events. Similarly, the way most of the people in Bassano's painting seem almost unaware of the others surrounding them shows that he does not emphasize an ennobling fellow-feeling among the suffers in the manner of Danby.

In contrast, Danby's Deluge seems to have escaped its conventional meaning, for clearly it portrays more of a slaughter of the innocents than a punishment of the guilty. Danby's dying men, women children, and animals forced us, whatever preconceptions (or paradigm allegiances) we bring to the painting, to sympathize with them. And to sympathize with those the Lord punishes is to become one of the Devil's party.

The Deluge by Joseph Mallord William Turner. Exhibited 1805 [?]. Courtesy of Tate Britain (N00493). Click on image to enlarge it.

Similarly, as the eye moves across Turner's Deluge (1813, Tate Gallery), one encounters images of men and women helping one another. We are carried from the kneeling Magdalen-like figure in the lower left corner to the group immediately beside and behind her in which a man upholds a nude woman to whom a young boy is changing. Next to this trio a leaning man tries to lift a woman from the water, while farther towards the contre we encounter the dramatic action of a parent trying to hold an infant from the waters. This emphasis upon saving children, which seems a characteristic of Romantic versions of the Deluge, appears in several other places in Turner's picture; and although helplessness and desperation colour his work far more than they do Danby's our final impression is of suffering innocents.

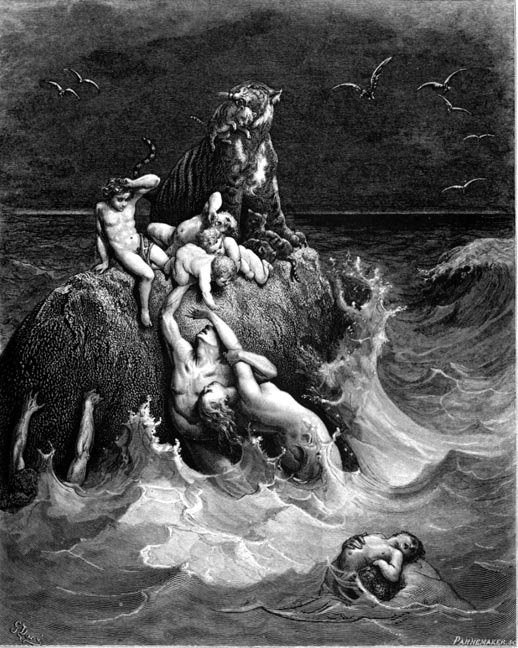

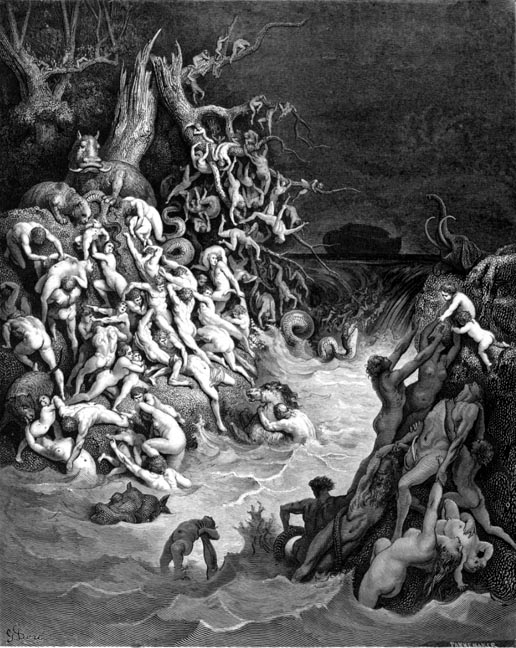

Two illustrations of the Deluge from Gustave Dor�'s The Holy Bible with Illustrations. 1866. [Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

Gustave Doré's famous Bible illustrations (1865) make it even clearer that a savage nature destroys innocent beings. Doré, who (as [142/143] Ruskin pointed out) loved to depict sensational violence, devotes three plates to the Flood, each more destructive of traditional readings than the last. In The World Destroyed by Water, we come upon many examples of panic as the seventy or so figures desperately attempt to escape the rising waters, but again there is none of the viciousness and cruelty one expects in scenes of panic. Indeed, a sense of community and humanity characterizes the acts of these people. In the foreground, for instance, a father heroically tries to hold wife and child above the waters, while above him two parents strain to push their infants to higher points of safety. In the centre of the plate the arm of a drowning parent rises from the water and holds up a child to grant it a few more moments of life. Similarly, in the pyramid of men and animals on higher ground which dominates the major portion of the illustration, love, fellowship, and community prevail: innocent children are pushed to the heights, and supposedly guilty human beings sacrifice themselves to save innocents.

In The Deluge Doré brings us closer to the end as only a few remain on a small bit of rock while the drowning waters close in, but once again the same heroism and dying innocence prevail. When the artist presents his interpretation of The Dove Sent Forth from the Ark, the last plate in this series, we observe the white bird at the centre of the picture as it flies through a valley of corpses. This voyage through a nightmare landscape of death makes the bird seem not a messenger of hope and grace, but a predatory avenging creature. In other words, in Danby, Doré, and Turner the subject takes on a new, particularly bitter meaning. The need to present visual images of divine punishment makes that punishment seem cruel and unusual indeed until, finally, one wonders if God had anything to do with it. The nineteenth-century imagination here destroys the traditional Christian significance of the Deluge in these works, twisting it and transforming it into something blasphemous, for the need to use one's sympathetic imagination, feeling and perceiving as if one were inside the scene itself, has betrayed some artists into creating subversive images and encouraged others to do so. I assume that Turner, a skeptic, quite consciously subverted the usual significances of the subject, and the same could be true of Doré, but Danby's general artistic approach, more than any conscious programme, is probably responsible for the transformation of the Deluge he creates.

At any rate, these artists' instinctive portrayals of the suffering inhabitants of earth result in images, not of men who suffer justly but of those who suffer and do not understand why — and neither do we, the spectators of these events. We encounter images not of a universe in which God rules, but one in which nature runs rampant We move, in other words, from the universe of the Bible and Evangelical hymnody to that of Melville. As his Ishmael tells us in

Foolish mortals, Noah's flood is not yet subsided: two thirds Of the fair world it yet covers. . . . The sea dashes even the mightiest whales against the rocks, and leaves them there side by side with the split wrecks of ships. No mercy, no power but its own controls it. Panting and snorting like a mad battle steed that has lost its rider, the masterless ocean overruns the globe. [ch. 58]

Anyone who shares this vision of nature and this vision of the Deluge is unlikely to take the Flood as an instance, a paradigm, of just punishment.

Related Materials

Tim Spalding's Noah's Ark on the Web ("an annotated guide to Noah's Ark in art, religion and culture.")

Last modified 12 July 2007